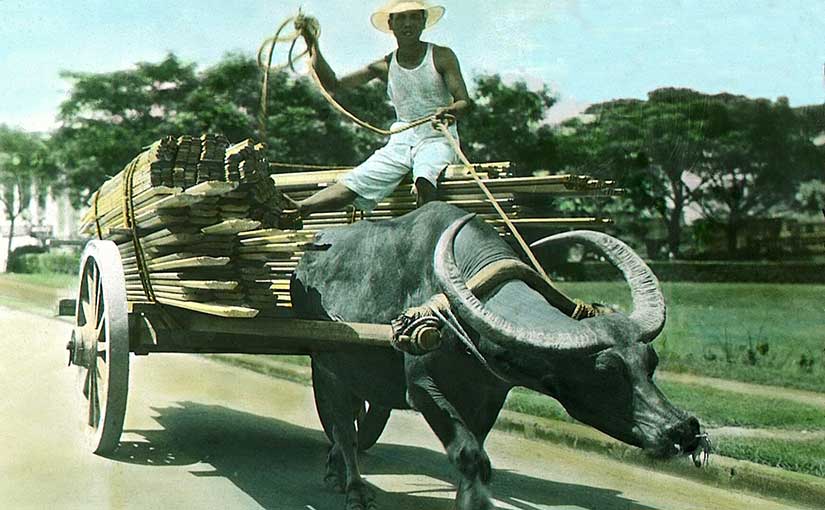

The carabao is the national animal of the Philippines. It’s a good choice because this beast of burden can do everything. It can haul a house’s worth of goods (up to 3500 kilos or 7700 pounds), turn a mill stone, or carry several passengers for hours. It is your pick-up truck, tractor, and engine all in one. A contemporary observer wrote that the carabao was “patient and tractable so long as he can enjoy a daily swim. If cut off from water the beast becomes irritable [and] will attack men or animals and gore them with its sharp horns.” Americans were a bit dramatic, of course. They resented the carabao for clogging carriage traffic as it lumbered through Manila at two miles per hour.

The true test of the carabao’s usefulness is that there are still 3.2 million in the Philippines. According to a 2005 United Nations report, “99 percent belong to small farmers that have limited resources, low income, and little access to other economic opportunities.” At the dawn of the 20th century, though, every farmer and hacendero relied upon the carabao, which is why the rinderpest epidemic of 1901 hurt the islands so badly. This was one of Javier Altarejos’s biggest problems at the beginning of the book: finding the money to replace his herd.