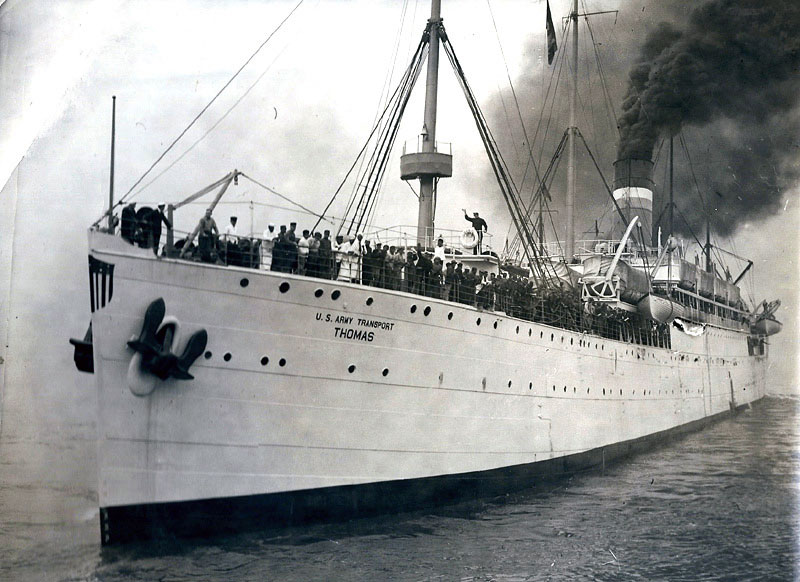

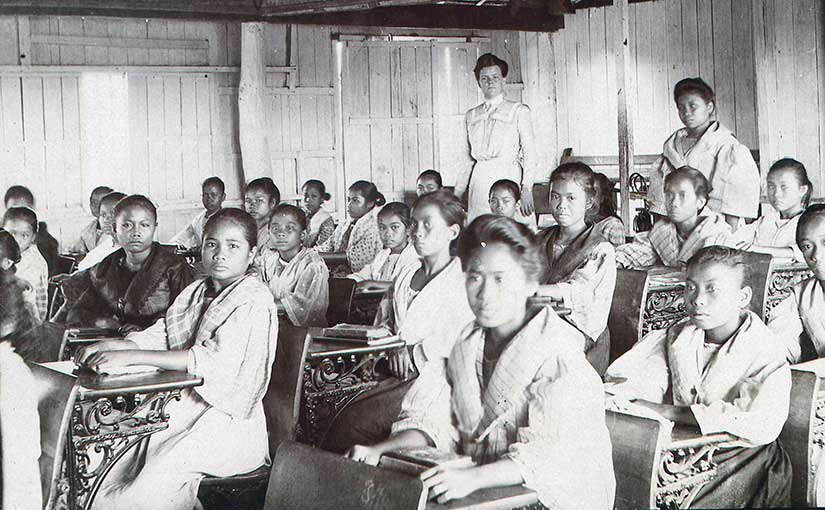

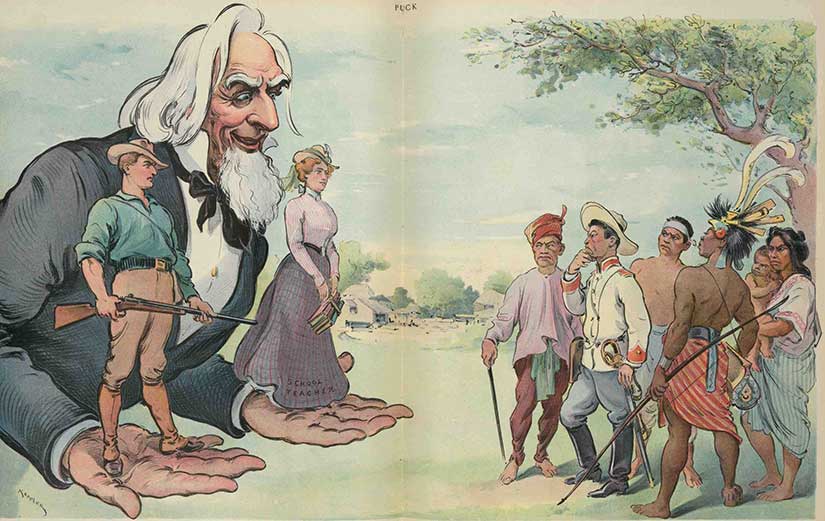

In August 1901 over five hundred American teachers arrived in Manila aboard the USAT Thomas, and the term “Thomasite” was born. A strategy begun by the Army to “pacify” the islands, the American colonial authorities established a coeducational, secular, public school system throughout the Philippines. Often seen as the best thing the Americans did in the islands, it is not without its critics. Here’s the good, the bad, and the ugly.

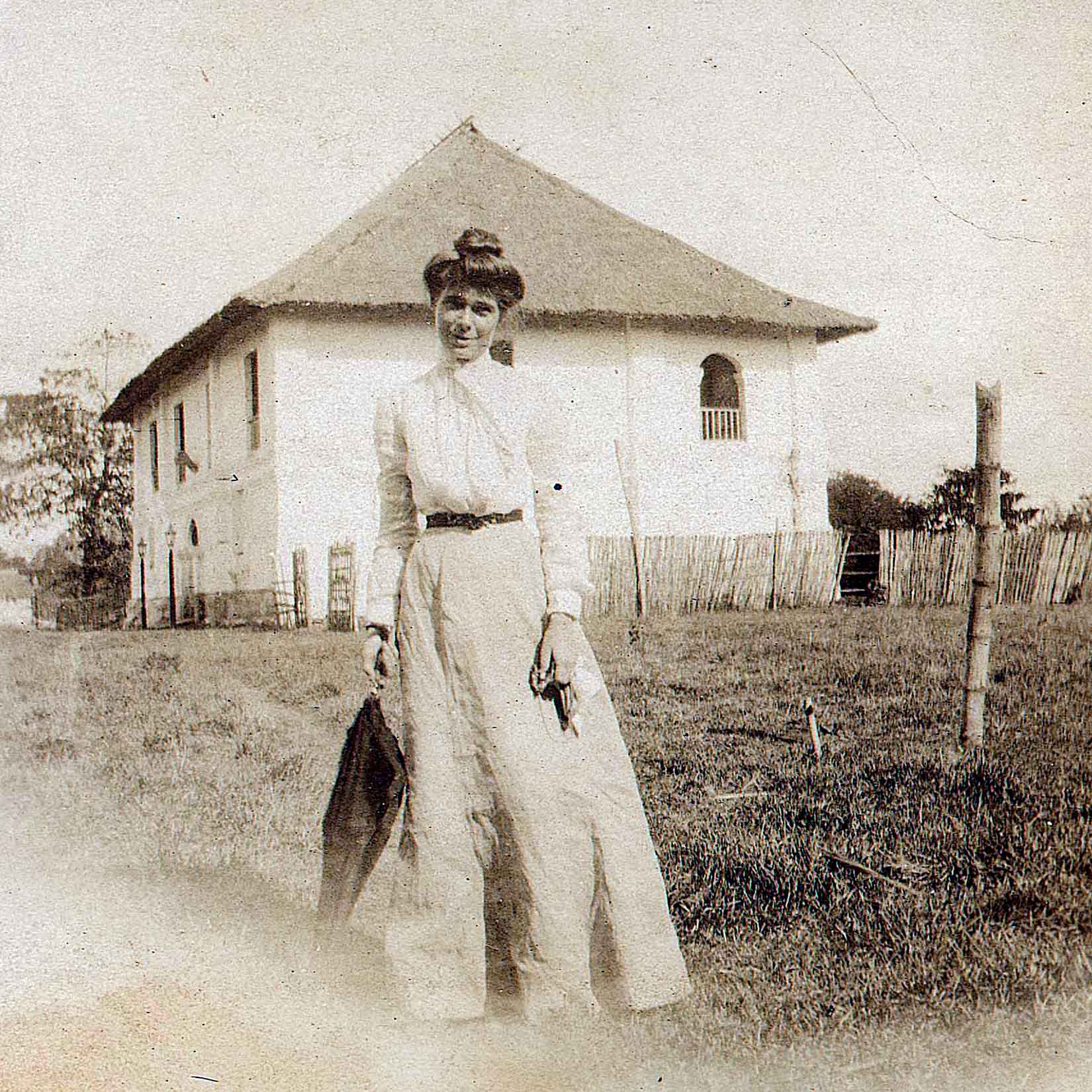

The Good: Many Thomasites were flexible, adventurous people who truly loved their students and their host towns. Some never left. I modeled Georgina Potter on some of these people, including Mary Fee, who will come up again. The best, most democratic administrator was David Barrows, who emphasized solid academic subjects like reading, writing, and arithmetic so that Filipinos could find professions, not just jobs. He also implemented a test-based scholarship system to American universities. Barrows opened more schools and trained Filipino teachers to take them over—something now termed sustainable development.

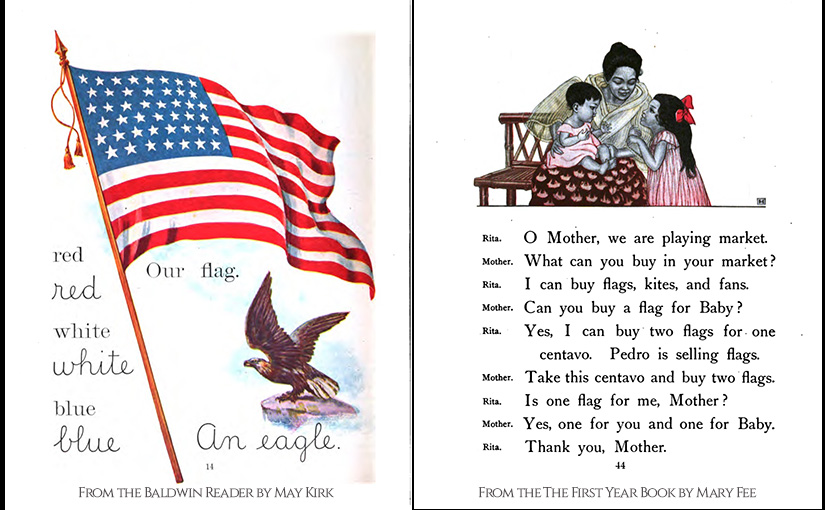

The Bad: In his time, Barrows was considered a failure because Filipino students were not achieving to the level of Americans in standardized testing—yes, back then we were just starting to “teach to tests.” A thinking person might understand that this is because Filipino students were being taught in a foreign language. This is a good time to mention that everything was taught in English. Why? The Americans said that Filipinos had not learned enough Spanish to justify that medium, and the local languages were too many and too varied to be practical. Most importantly, the Americans—particularly the Easterners and Midwesterners who came to the Philippines—only spoke English. Moreover, they already had the textbooks printed. Hence, Filipino boys and girls were learning poems about…snowflakes? Fortunately, Mary Fee and others rewrote some of these early readers with local themes, proving that not all Yankees are idiots.

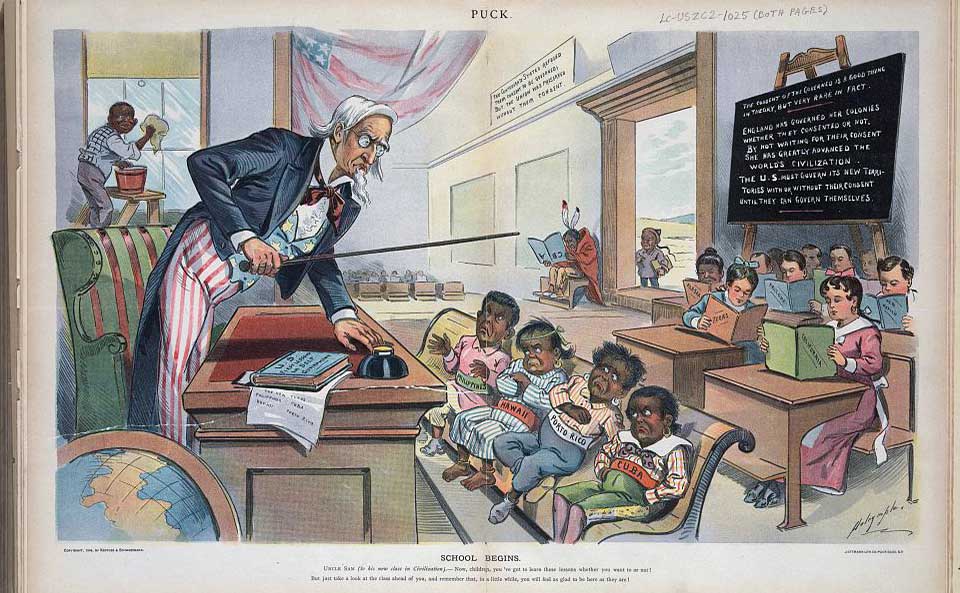

The Ugly: The next superintendent after Barrows returned the educational system to its original focus: industrial education, based on what were then called “negro schools” in the States. White (really his name) thought that Filipinos should be taught “practical subjects” like carpentry and gardening, as well as “character training” like cleanliness and conduct. (Such prejudice was so prevalent at the time that English-speakers had not yet coined the word “racism.” It was simply the norm.)

And then there were some individual Americans who, in the words of Javier Altarejos, were “unfit for travel abroad.” Harry Cole, stationed in Palo, Leyte, wrote that “when I get home, I want to forget about this country and people as soon as possible. I shall probably hate the sight of anything but a white man the rest of my life.” My antagonist, Archie Blaxton, channels good ol’ Harry quite a lot. (I did not have to make up horrible, racist stuff for my characters to say. I just looked up what real Americans did say. It was not encouraging.)

In the end, the educational program was successful in making Filipinos believe that a brighter future was possible under the Americans—not fighting the Americans. Whether this was cynical manipulation by the colonial government or a sincere intention to do good abroad, that’s up to you to decide. From my research, the two were tied up together in what President McKinley termed “Benevolent Assimilation.” Many Filipinos did like the schools, and they certainly respected their teachers. Most importantly, some families managed to do what Barrows wanted: to “destroy that repellent peonage or bonded indebtedness” in which they found themselves. And the Thomasites gave me great plot ideas, so I’m not complaining.