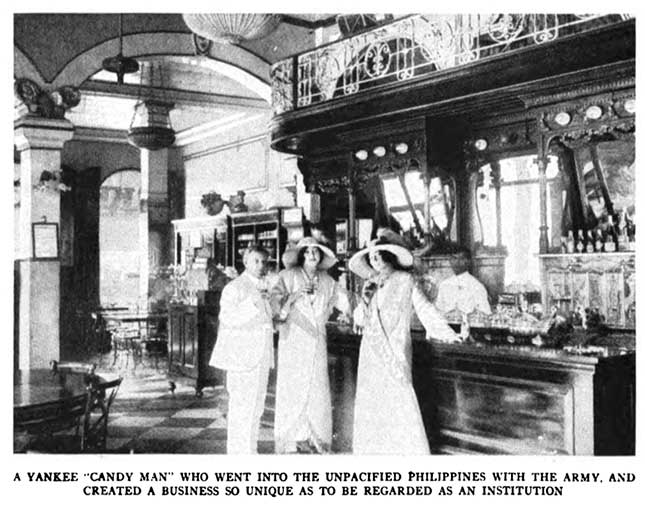

Early on in Hotel Oriente, our heroine Della ventures to the most “swell” confectionery in Manila, Clarke’s Ice Cream Parlor:

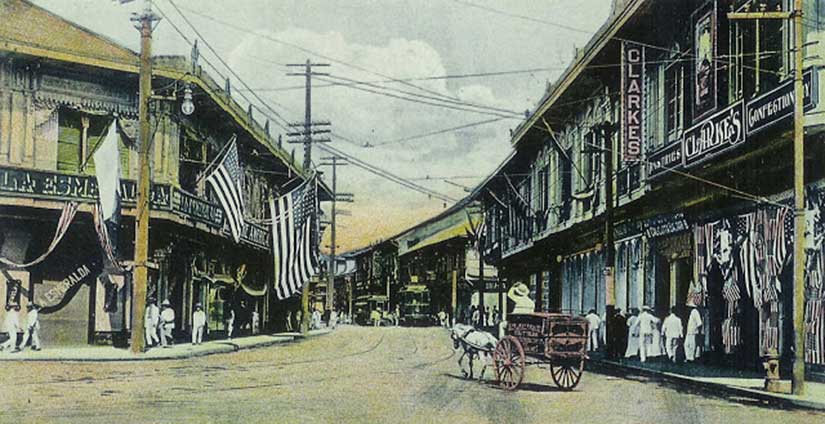

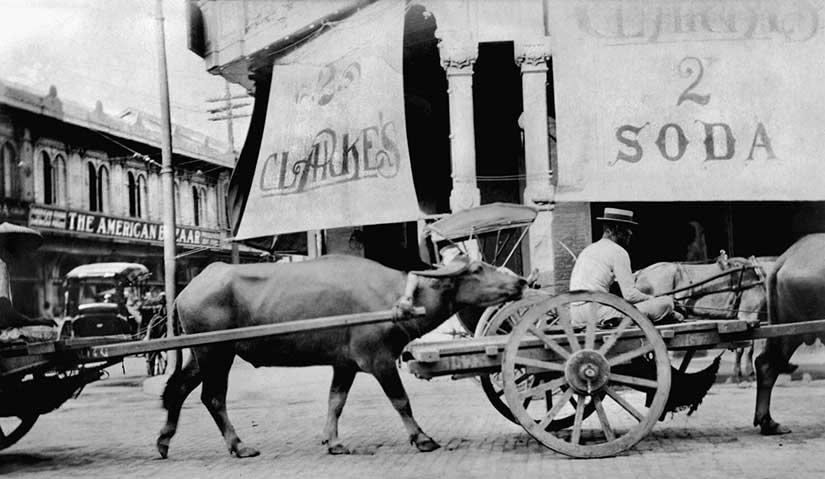

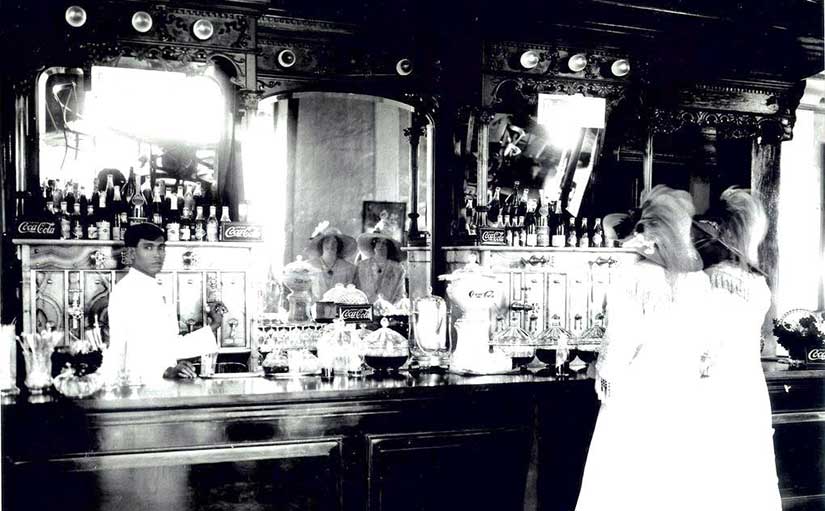

Located at the entrance to Escolta, Manila’s Fifth Avenue, the establishment proudly proclaimed its name on both the roof and on a half dozen oversized awnings facing every direction. Even without the signage, the place was clearly marked by a large crowd. The spacious wood-paneled room was full of businessmen and civil servants from all over the islands, officers of the army and navy, and tourists from half the world.

Clearly, M. A. “Met” Clarke, a native of Chicago, knew an opportunity when he saw it. In August 1898, only four days after the landing of American soldiers in Manila, he arranged a long-term lease in this fashionable shopping district. As one visitor wrote:

To the American bred boys in khaki, the place quickly became known as an oasis in a desert. Weary, thirsty, hungry, and wet with perspiration, the commands coming from or going to the firing lines halted there long enough to quench their thirst or to fill the aching voids. Incidentally, the soldiers helped Clarke along by spending their money freely.

Later Clarke would sublet a slate of rooms on the second floor, and his monthly income from these rents would pay his entire annual premium. But Clarke could not have been so successful if his food had not been exceptional. Fortunately, it was.

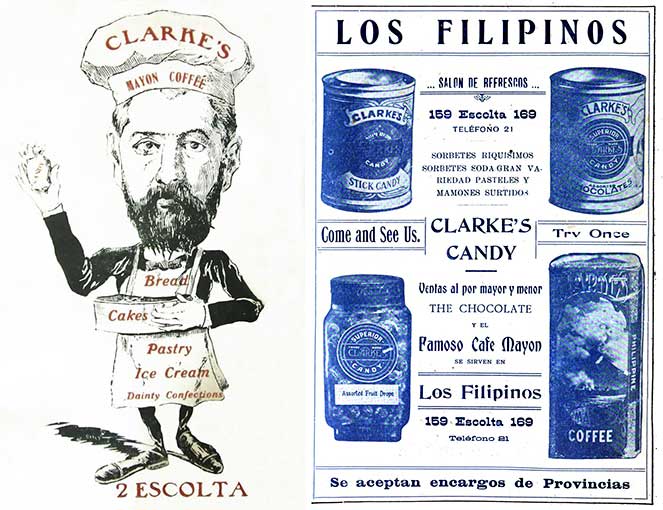

Clarke’s was the place to find the best gingerbread, the best candy, and the best pink (condensed milk) ice cream in Manila—and maybe in all of Asia, according to the foreigners who lived there.

Despite being an ice cream and soda fountain, though, Clarke’s real claims to fame seemed to be bread and coffee. Clarke had three 16 x 18 foot ovens that turned out 36,000 pounds of bread a day. For our character Della, the value of fresh bread cannot be underestimated: “After three days of the atrocious food at the Hotel Oriente, her stomach almost jumped out of her throat to lay claim to a loaf.” (See more on the hotel’s disappointing food in the American era in the next post.)

Moreover, the coffee was locally grown in Luzon and roasted by Clarke himself. (I used to have a farm in Indang, Cavite, and they still grow beans in town and dry them out on every road and driveway available.) But don’t take my word for it. Read a contemporary account:

Clarke’s Coffee!—its delicious and aromatic flavor is suggestive of Arabian poetry and romance of deserts and camels of swift steeds and beautiful women. The beverage itself exhilarates you, gives you a feeling of buoyancy. Perhaps you are a connoisseur of coffee, and during your travels in Oceania or China you have been nauseated with the horrible concoctions served to you in hotels and on steamers—the vile black liquid that they call coffee. If you are, Clarke’s is the place for you. The coffee served to you there, nicely, daintily, temptingly, will make you smile with satisfaction, and you will begin to understand how the Americans do some things in Manila.

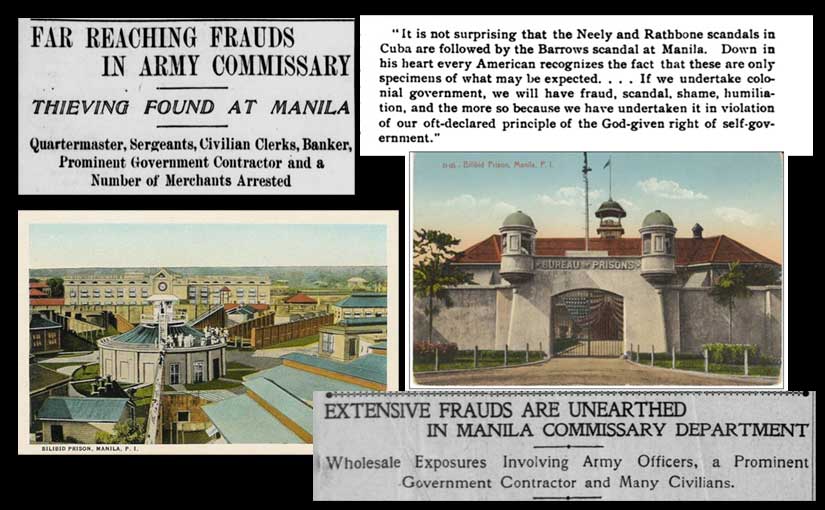

Clarke would have been the next Midas of Manila had he “not been a plunger,” according to the Magazine of Business account. He made and lost a fortune in gold mining and hemp-stripping machines. But this is the way of the early American period in the Philippines. Respectable businessmen (and women) had no reason to cross the Pacific. Those who did make the trip were often hucksters, carpetbaggers, and scoundrels. Clarke seemed one of the better of the lot, since he was not implicated in the quartermaster embezzlement scheme that rattled Manila in 1901 (and was the inspiration behind the scandal in Hotel Oriente):

Of course, Moss, our hero of Hotel Oriente, is not so certain that Clarke is innocent, just that he is crafty: “As if the police would know where to look,” he says. “That man has more warehouses than the Army itself.”

Sadly, Clarke’s empire was only to last until about 1911, when his losses in the mining industry sent him swimming back to California. Or did he really leave? Maybe he just changed his name to Starbuck…