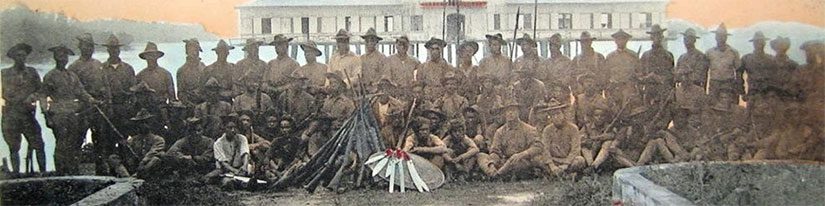

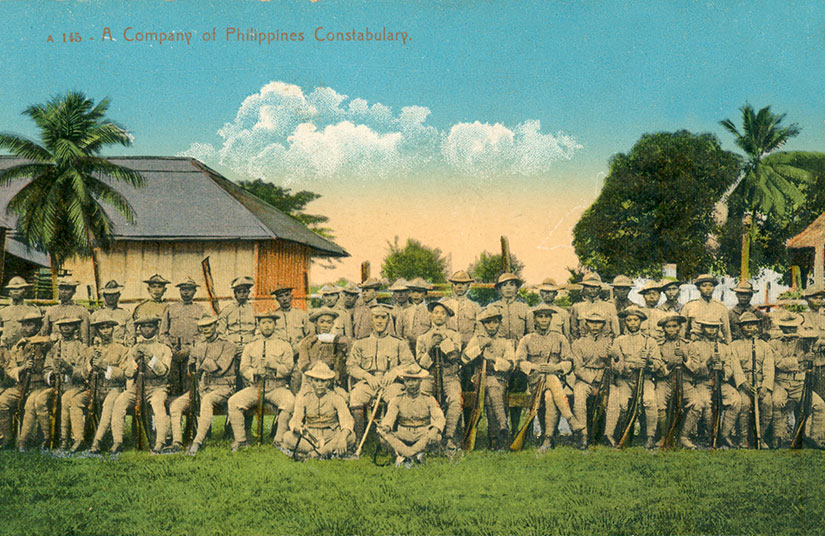

Despite President Roosevelt’s declaration that the Philippine-American War was over in 1902, there was actually still a lot of fighting to do. Combat was largely turned over to two new Philippine services: the Constabulary (police) and the Scouts (army), both of which were organized and administered by the American colonial government. Noncommissioned officers and junior officers in the US Army were tapped to become officers of these services as they started out. One of these men would become a beloved figure in Manila: Philippine Constabulary Band leader, Lt. Col. Walter Loving.

As a colonial army, leadership positions in the Constabulary were not equitably distributed. For starters, officer positions were not granted to Filipinos at all (Talusan 2004, 501). Secondly, discriminatory practices still benefited white officers over African Americans, despite the latter being preferred by Filipinos. A Filipino physician told Sergeant Major John W. Calloway, a Black soldier who was working part-time as a reporter from the Richmond Planet: “Between you and him we look upon you as the angel and him the devil” (“Voices from the Philippines” 1899, 1).

White leaders justified their continued segregation and discrimination with the supposed poor performance of African American soldiers—but this claim simply wasn’t true. In fact, it had already been proven untrue in the Spanish-American War when the Ninth and 10th Cavalry and 24th and 25th Infantries saved Roosevelt’s own hide.

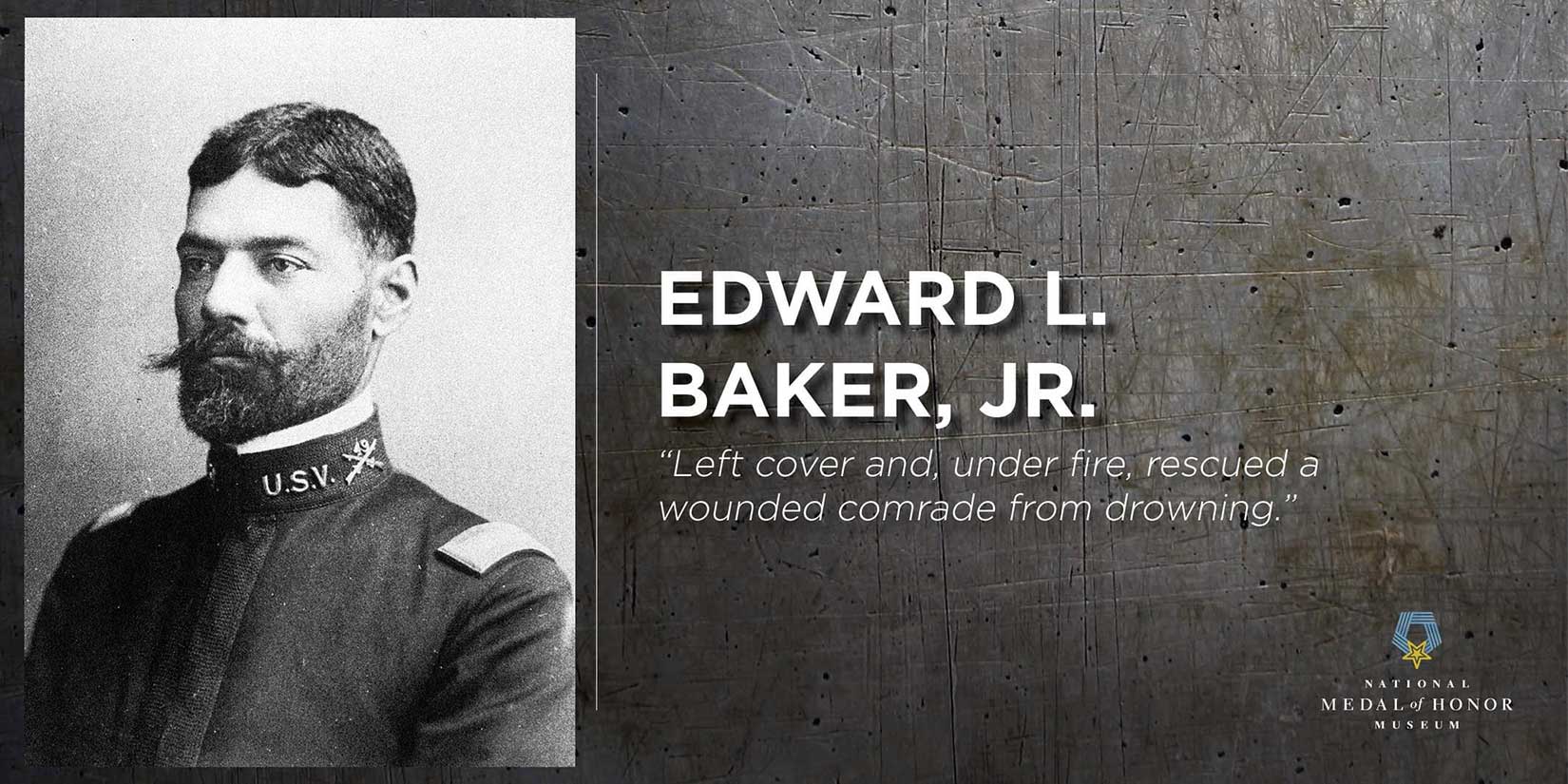

As an example of continuing discrimination, Edward L. Baker Jr. has to be one of the most overqualified second lieutenant in American military history. He had earned a Congressional Medal of Honor—the highest award for valor in action that can be awarded to anyone in the United States Armed Forces—while a sergeant with the 10th Cavalry in the Spanish-American War (National Park Service 2015). He then served as a first lieutenant, then captain, of African American volunteer regiments in the Philippines. When those regiments were disbanded in 1902, Baker joined the Philippine Scouts in 1902, but he was forced to accept a significant demotion (Cunningham 2007, 13). A second lieutenant is the entry level of an officer, right out of officer training, and that’s two grades lower than the captaincy that experienced veteran and Medal-of-Honor-winner Baker previously had.

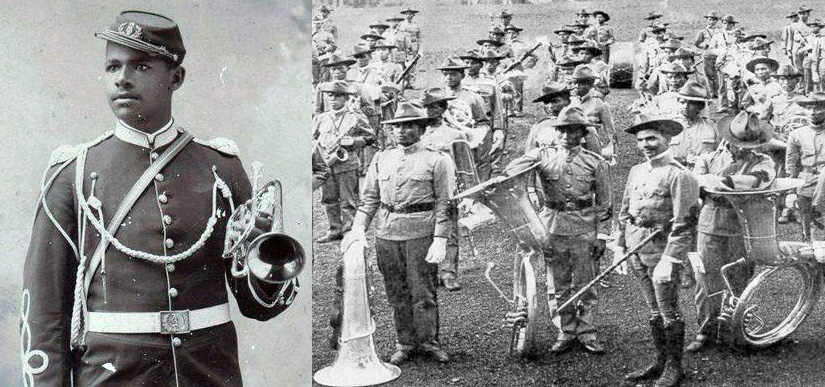

Second lieutenant was still an officer position, though, and this kind of promotion is what drove a veteran named Walter Loving to make his career in the Philippines. Loving was not a line officer but a cornet player. The cornet is a horn similar to trumpet but shorter and with a mellower tone. “Military bands were an important part of every regiment, and the Army’s Black bands enjoyed especially good reputations, perhaps because they were able to attract talented musicians with fewer opportunities for steady civilian employment” (Cunningham 2007, 6). Loving was one of those talented musicians. The Black chaplain of the 24th Infantry unit, Loving’s first regiment, wrote him a glowing recommendation as a “fine musician” and said that one day Loving “would be successful as a chief musician of a regimental band” (Cunningham 2007, 7). At this point, all the chief musicians in the permanently constituted regular army were white, and part of the reason for this may be pay: they earned more than other soldiers of their rank, and they had quartermaster privileges. Worse, these white officers were sometimes ex-Confederates (Gleijeses 1996, 193). Loving would later remark on this practice:

Even in Civil War days colored units carried colored non commissioned officers . . . that most of these white non commissioned officers view themselves in the light of the overseer of antebellum days is shown by their practice of carrying revolvers when they take details of men out to work (Quoted from African American Registry).

When Loving could not secure the post of bandleader, he decided to re-enlist in the 8th U.S. Volunteer Infantry, which served in Cuba. The white colonel of the unit said: “My colored officers and men have quietly submitted to slights and insults which would not patiently be borne by white troops, and I hope they will continue to do so in future. But each prejudice is a source of constant danger to regiments constituted as mine is and stationed in the South” (Cunningham 2007, 8). When the entire regiment was mustered out, for example, they were “roughed up” by the police as they passed through Nashville on the train (Cunningham 2007, 8). It was with the 8th USVI that Loving was finally promoted to second lieutenant to become the chief musician of the band—but since the volunteer unit was a temporary one, his commission was temporary too. (Think of volunteer units as having an expiration date. Most enlistments in them were a year, and the units were disbanded once they were no longer needed. This is what had happened to Baker too.)

Loving returned to school at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where his professor wrote that “his progress had been ‘very remarkable’ and that the mark he had attained as a cornet soloist had ‘never been surpassed since this Institution . . . organized its special course for the cornet’” (Cunningham 2007, 9). Loving did not stay to complete his degree, though, because war in the Philippines lured him back into the service.

While serving as the chief musician for the 48th US Volunteer Infantry, another temporarily-constituted unit, his commanding officer said to him: “The high state of efficiency to which you have brought the band when hardly two men knew how to make a note when they first reported seems almost beyond belief, and the development of the regimental chorus of four hundred voices all bear witness to your ability” (Cunningham 2007, 10). (This perspective is flattering to Loving but not to the Filipino musicians, who had a long tradition of excellent music. More on that in a bit.)

But then the 48th USVI was mustered out too. What would Loving do now? He sought the assistance of Vice President Theodore Roosevelt—a friend of his sister’s employer—to secure a position as a messenger in the U.S. Senate. Roosevelt wrote his regrets, saying that “he already had a ‘colored messenger, . . . and the other messengers are appointed by the individual senators. They would not tolerate any advice from the Vice President about them” (Cunningham 2007, 10). Next, Loving sought a position with the Philippine Scouts, and he again asked for Roosevelt’s help. “Although Roosevelt had previously assured [Julia’s employer] that he was willing to help Loving, he instructed his secretary to inform the War Department that he did not ‘wish any unusual action taken’ in the case, and the Scout commission never materialized” (Cunningham 2007, 10).

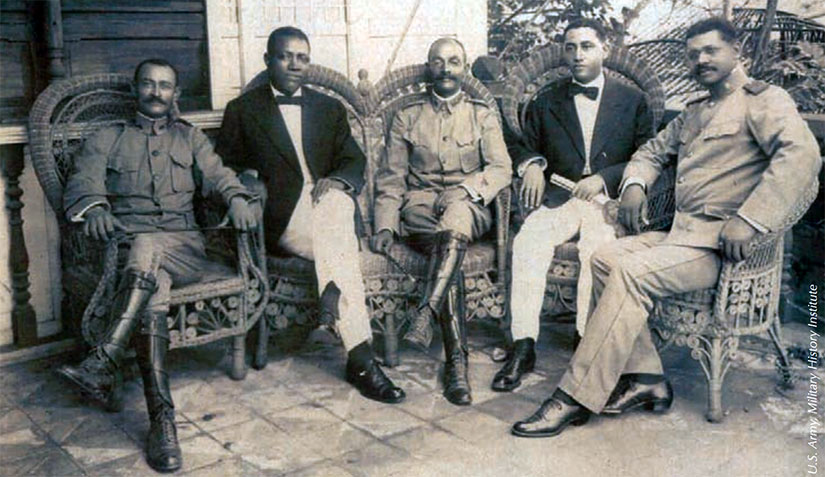

Finally, things did turn around. Loving was able to return to the Philippines in 1902 as a second lieutenant for the Philippine Constabulary under General Henry T. Allen. “Loving was lucky to serve under Allen because the general had a relatively high opinion of African American (and Filipino) capabilities. As Allen’s biographer has pointed out, his ‘moderate racial views put him in the minority among the senior officers of his day’” (Cunningham 2007, 11). That is faint praise now, but Allen’s word meant something to Governor Taft, who then tapped Loving to form a Constabulary Band. Actually, this was something Taft had promised to do back when Loving was still with the 48th USVI, but with Allen’s push he finally made good on his word.

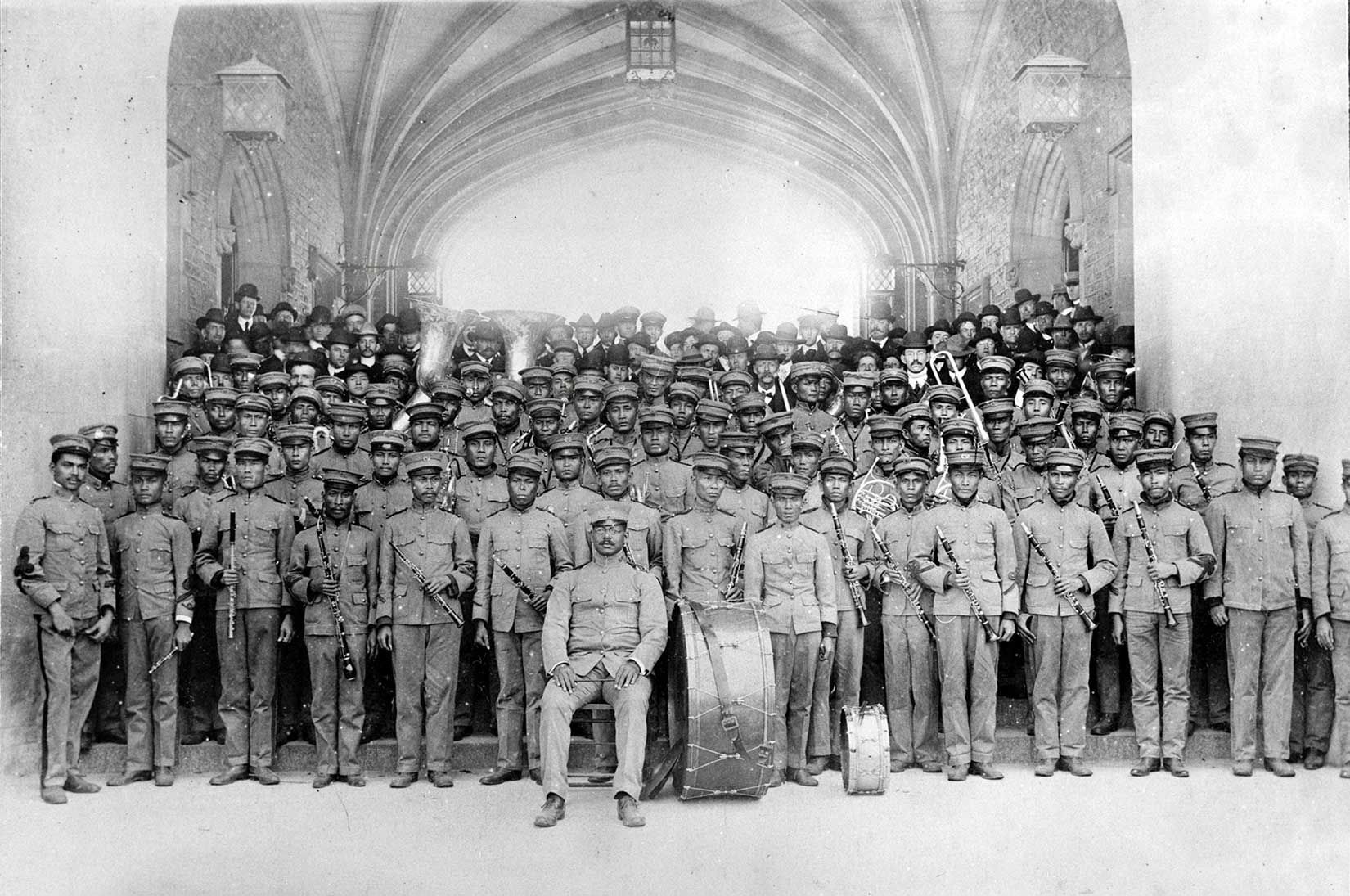

Loving would have a lot of talent to work with. According to scholar Mary Talusan:

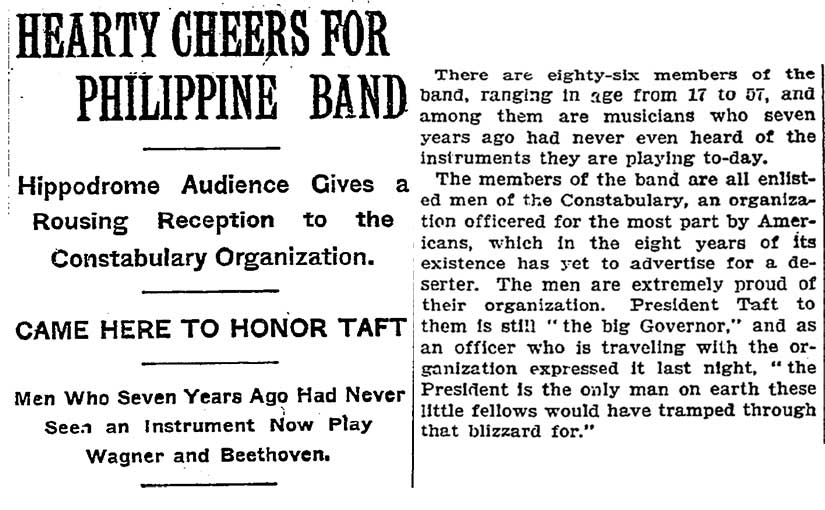

The men who formed the original Band were some of the most promising musicians of their time. Some of them descended from a long line of small town band musicians or were former members of regimental bands under Spanish rule. Others were already enlisted in infantry bands under U.S. control, and a few were “trumpeters who had served under Aguinaldo” (Richardson 1983, 9). Most men came from or lived in the Manila area, but a few were from the llocos, Visayas, and other places.

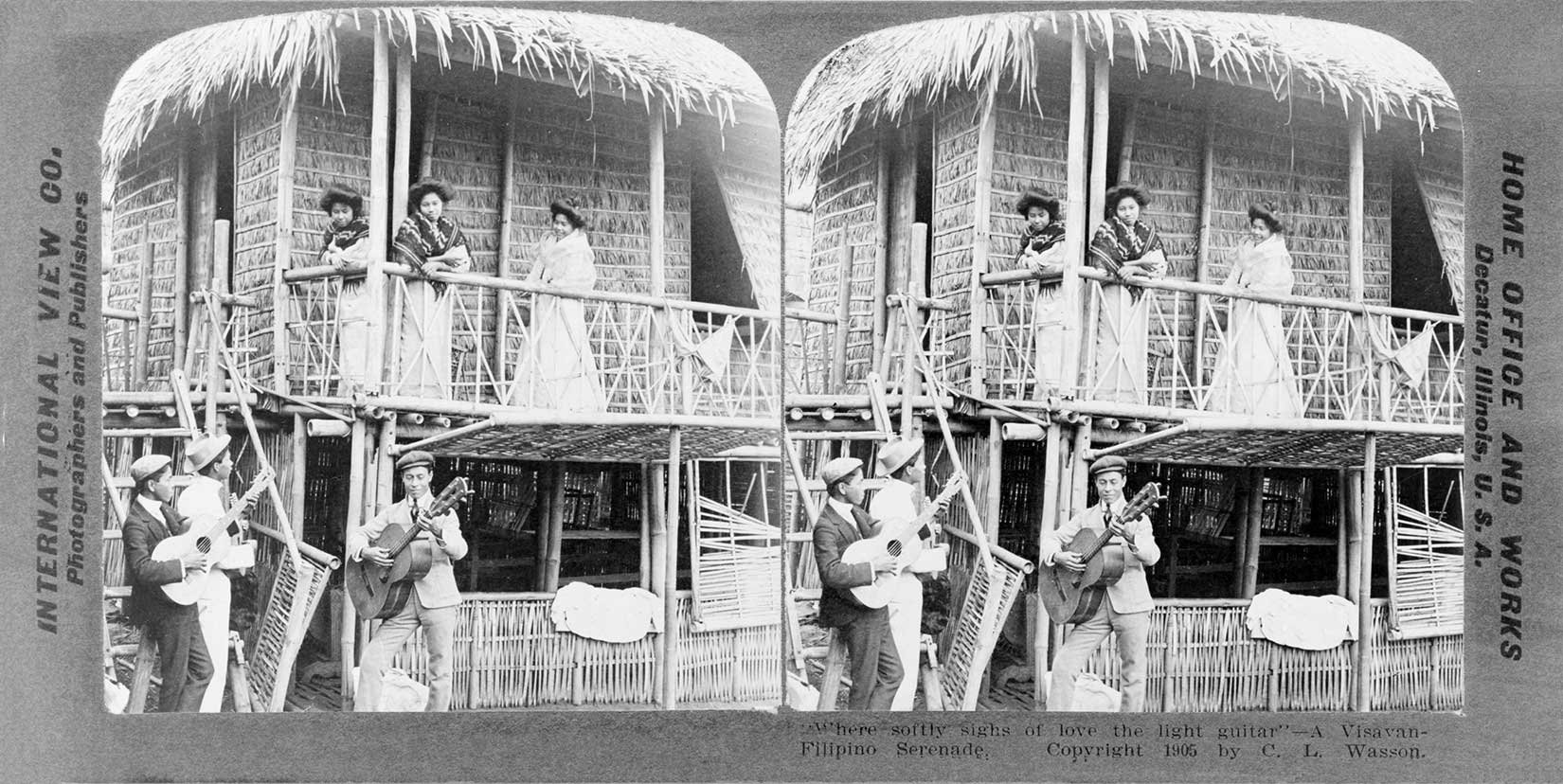

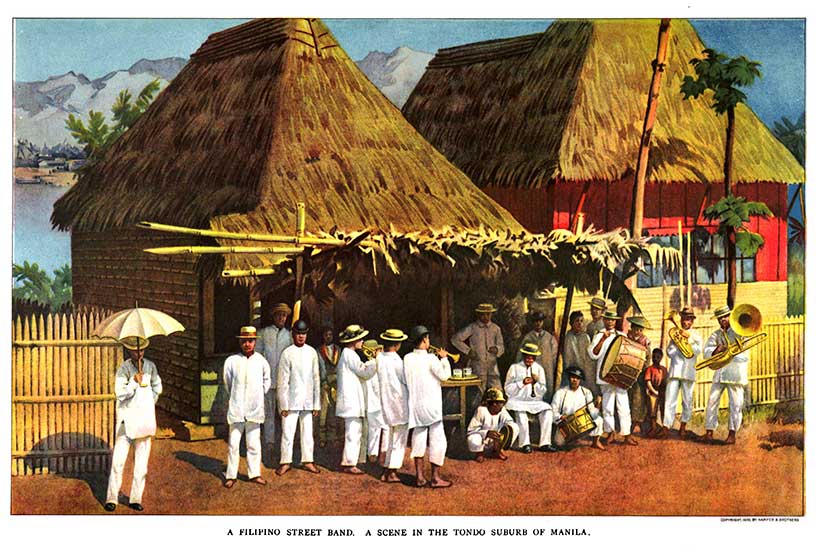

The Philippines had long valued music in the home, on village streets, and in military bands. Town bands played at fiestas, marriages, funerals, baptisms, and just for weekend fun. Competitions between local bands would last for days. Instruments were handed down from parent to child, but there was also formal musical education available (Talusan 2004, 506-7).

Outside of religious institutions, European classical music was taught in boys’ colleges, normal schools for boys, the Ateneo, the University of Santo Tomas, the Beaterio Colleges for girls, and also privately. Filipino elites and intellectuals actively supported the performances of concerts and operas by individuals, visiting organizations, and local art and literary societies with musical components. Ilustrados (educated elite who studied in Europe) brought back and kept in touch with the musical scene in Europe. Orchestras performed for a widely popular native form of opera called sarsuela (Talusan 2004, 506).

Musicians and audiences embraced the new Constabulary Band, and it would become a regular feature during evenings at the Luneta. Even more importantly, the skilled Filipino musicians embraced Loving’s leadership:

I have heard many stories from [the family of Loving’s protege, Pedro B. Navarro] of the great respect that the bandsmen had for Loving as a leader, musician, and officer. He was described as a very strict, principled, and compassionate man, and the bandsmen were fiercely loyal to him. My great-aunt, Leonora Navarro, related that Loving would often eat dinner with their family. In addition to their profound relationship as musicians, Loving’s command of Spanish certainly fortified their connection. During those times many Filipinos used Spanish as a language of resistance against American hegemony, since many Americans in Manila could not speak it. By using Spanish to communicate the bandsmen and Loving created for themselves a space for camaraderie and resistance (Talusan 2004, 510).

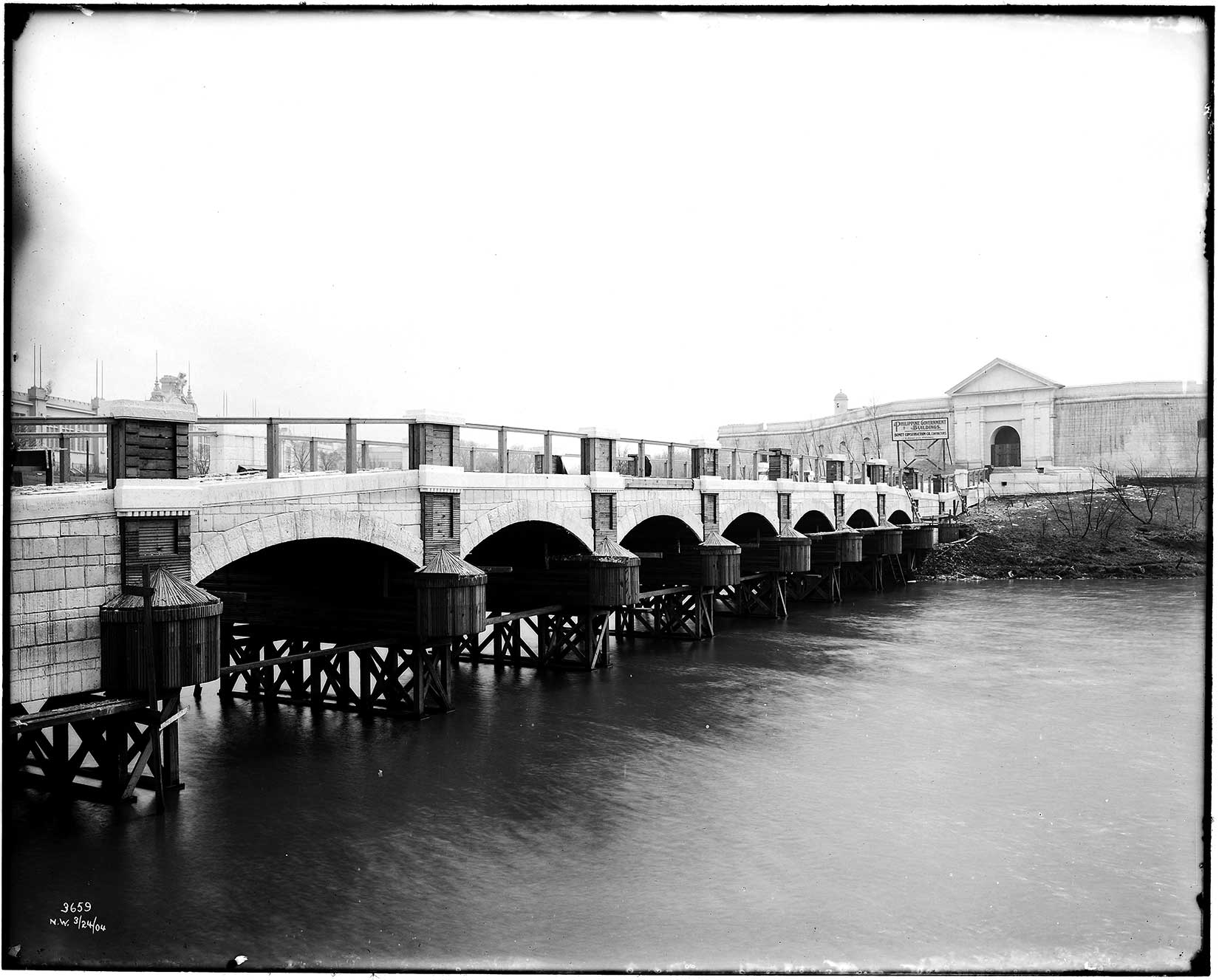

Loving also learned some Tagalog, the language of Manila and nearby provinces. He was promoted to first lieutenant in 1903 (Cunningham 2007, 11), and in the next year he would bring his band to the United States to be one of the most popular attractions at the 1904 World’s Fair, also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, in St. Louis. This experience was one of the highlights of Loving’s early career, but it was not without its challenges. The experience of Filipinos and African Americans at the World’s Fair was a pointed illustration of the assimilationist racism of American imperialism at the turn of the century (Kendi 2017):

Loving, as a Negro officer in military uniform, might have been perceived by audience members as having been assimilated and made successful by American tutelage and training. He seemed to confirm the trope of “benevolence” by embodying America’s democratic rather than racist principles. In sharp contrast, African American groups were kept from participating in the fair and their representation was limited to the nostalgic “Old Plantation” exhibit. The few Black fairgoers that did attend were excluded from water fountains and restaurants. . . . In fact, I found no references to Loving’s race in any of the public documents of the Fair, suggesting that, since he could not be contained in the discourse of [racist] evolutionary hierarchy, his racial identity was better left unidentified (Talusan 2004, 519).

For the Filipinos of the Constabulary Band, the World’s Fair was a forum to showcase their talent on a world stage:

During one evening concert, the band especially impressed its audience when the power went out and the Filipino musicians continued to play the William Tell Overture in the dark, without missing a note. Loving, who quickly tied a white handkerchief to his baton so that it could be seen, had insisted that his men memorize their repertoire (Cunningham 2007, 12).

As scholar Mary Talusan argues, it may have been possible for both groups to serve their own agendas simultaneously in St. Louis:

Such representations in America’s expositions encouraged American fairgoers to marvel at the civilizing effects of the U.S. on the Philippines, legitimizing the contentious way by which the Philippines was brought under its custody. In this way, the United States government’s exhibition of Filipinos at the St. Louis Fair can be seen as a successful effort to construct an image of the ideal colonized person, one who embodied an identity characterized by passivity, obedience, and perhaps gratitude through the convergence of military and musical performance. By contrast, the Filipino elites who worked with the American colonial government in organizing the Fair and, to a large extent, the musicians themselves viewed the accomplishments of the PC Band in nationalist terms, emphasizing rather than obscuring Filipino musical traditions established at least a century prior to American rule. . . . American colonialists did not always succeed in binding colonial subjects to their proper place—individual agency and acts of resistance were never fully restricted or contained, especially in the arena of human creativity (Talusan 2004, 500).

The white colonel who oversaw the Constabulary’s trans-Pacific voyage suggested that Loving “richly deserved” a promotion—which happened a month later as Loving was made captain. And it was because of Loving that President Roosevelt told the War Department that the white chief musicians in the regular army should be shifted to white units, clearing the way for African Americans to be promoted in their place (Cunningham 2007, 13-14).

Most visible of all, when Taft won the US presidential election, he invited the band to play at his 1909 inaugural festivities, which happened to be in the middle of a blizzard. They also played at the opening of the Potomac Drive, a copy of the Philippine Luneta, established by the Tafts. “To pay for the $20,000 cost of their trip, the Constabulary Band played cities all along their routes, from Nagasaki to Washington, even in the White House, and back” (Cunningham 2007, 15-16). On the way back, John Paul Sousa, the most famous white composer and conductor of martial music, said the Constabulary Band was better than the (white) United States Marine Band, Sousa’s alma mater (Cunningham 2007, 15).

Thanks to Elrik Jundis for finding this cylinder audio archive recording of the Banda de la Constabularia Filipina, courtesy of the University of California at Santa Barbara Library. The cylinder was published in 1910, which means it is likely a recording from the 1909 tour.

We should be careful not to praise Sousa in the matter, especially considering his assimilationist racist attitude towards ragtime music. He played some ragtime because it was popular, but he felt he had to “put a clean dress on it” (Quoted in Talusan 2004, 516). Loving seemed unable or unwilling to incorporate any African American music into his concerts Stateside, possibly because he was given less leeway. “As long as Loving and the bandsmen operated within acceptable parameters without overtly threatening the existing social order, they were allowed inside and commended in the military, the concert hall, and historical record” (Talusan 2004, 516). He stuck to the unwritten rules.

Loving eventually retired from the Constabulary as a major in 1916, and—after a brief civilian sojourn in California—he returned to US Army service as an undercover officer reporting on Black socialists, one of the most controversial parts of his life. Interestingly, it is in this questionable work he was given his highest promotion in the US Army, to major. He would have argued that this position allowed him to work from within to advocate for changes in military practices—such as not allowing southern white officers to command African American regiments. But he also spied on antiracist activities of Black communities throughout the United States, hurting the very cause he championed (African American Registry).

In the 1930s, Loving returned to Manila and was promoted to lieutenant colonel by Philippine Commonwealth President Manuel Quezon (Cunningham 2007, 16, 19). On a sad note, Loving would be imprisoned at the University of Santo Tomas during World War II until he was released to live under house arrest either at the Manila Hotel (Davis 2016) or a house in Ermita (Cunningham 19)—a rather unusual move for the Japanese command, supposedly in deference to Loving’s age and declining health (Cunningham 19).

Loving would die in Manila at the hands of the Japanese during the Battle of Manila in 1945. There are many stories of how he died: one explanation simply says Walter and his wife were separated by a Japanese soldier, and that was the last anyone saw of him (Cunningham 19); another claims that he refused preferential treatment by the Japanese to be beheaded with other Americans; another gives him credit for barricading a stairwell of the Manila Hotel so that fellow Americans could escape, causing him to be bayonetted and killed (Davis 2016); and a final story wrote that after Loving was shot in the back by retreating Japanese, he “half-walked and crawled to the Luneta, an open park where his famous band had many times thrilled the populace” where “the famous soldier and band leader drew his last breath” (Loeb 1945, 8).

After his death, Loving was posthumously awarded the Philippine Presidential Medal of Merit and the Distinguished Conduct Star, the second-highest military honor in the Philippines. What would have made Loving even happier, though, was seeing his son, Walter Loving, Jr., serve as an artillery captain during the Korean War, after the desegregation of the armed forces following World War II. Loving’s son would retire as a full colonel in 1969 (Cunningham 2007, 19).

SELECTED Bibliography:

Cunningham, Roger D. “The Loving Touch: Walter H. Loving’s Five Decades of Military Music.” Army History, Summer 2007, 4-25. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://history.army.mil/armyhistory/AH64(W).pdf.

Davis, Collis H. “Leader of The Band.” Positively Filipino. Last modified April 13, 2016. Accessed September 5, 2020. http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/leader-of-the-band.

Gleijeses, Piero. “African Americans and the War against Spain.” The North Carolina Historical Review 73, no. 2 (1996): 184-214. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23521538.

Kendi, Ibram X. Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. New York: Bold Type Books, 2017. Kindle edition.

Loeb, Charles H. “Eyewitness Tells How Famous Bandleader Was Slain by Japs.” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), April 14, 1945, 8. Accessed September 5, 2020. https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=TB0mAAAAIBAJ&sjid=wP0FAAAAIBAJ&pg=3008%2C4087694.

National Park Service. “The Philippine War: A Conflict of Conscience for African Americans.” Presidio of San Francisco. Last modified February 25, 2015. Accessed July 3, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/prsf/learn/historyculture/the-philippine-insurrectiothe-philippine-war-a-conflict-of-consciencen-a-war-of-controversy.htm.

Talusan, Mary. “Music, Race, and Imperialism: The Philippine Constabulary Band at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.” Philippine Studies 52, no. 4 (2004): 499-526. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42634963.

“Voices from the Philippines: Colored Troops on Duty—Opinions of the Natives.” Richmond Planet. (Richmond, Va.), 30 Dec. 1899. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/1899-12-30/ed-1/seq-1/.

“Walter Loving Born.” African American Registry. Accessed September 5, 2020. https://aaregistry.org/story/walter-loving-born/.