[This is the first in a series of three posts on the Pulahan War. Find links to parts two and three here.]

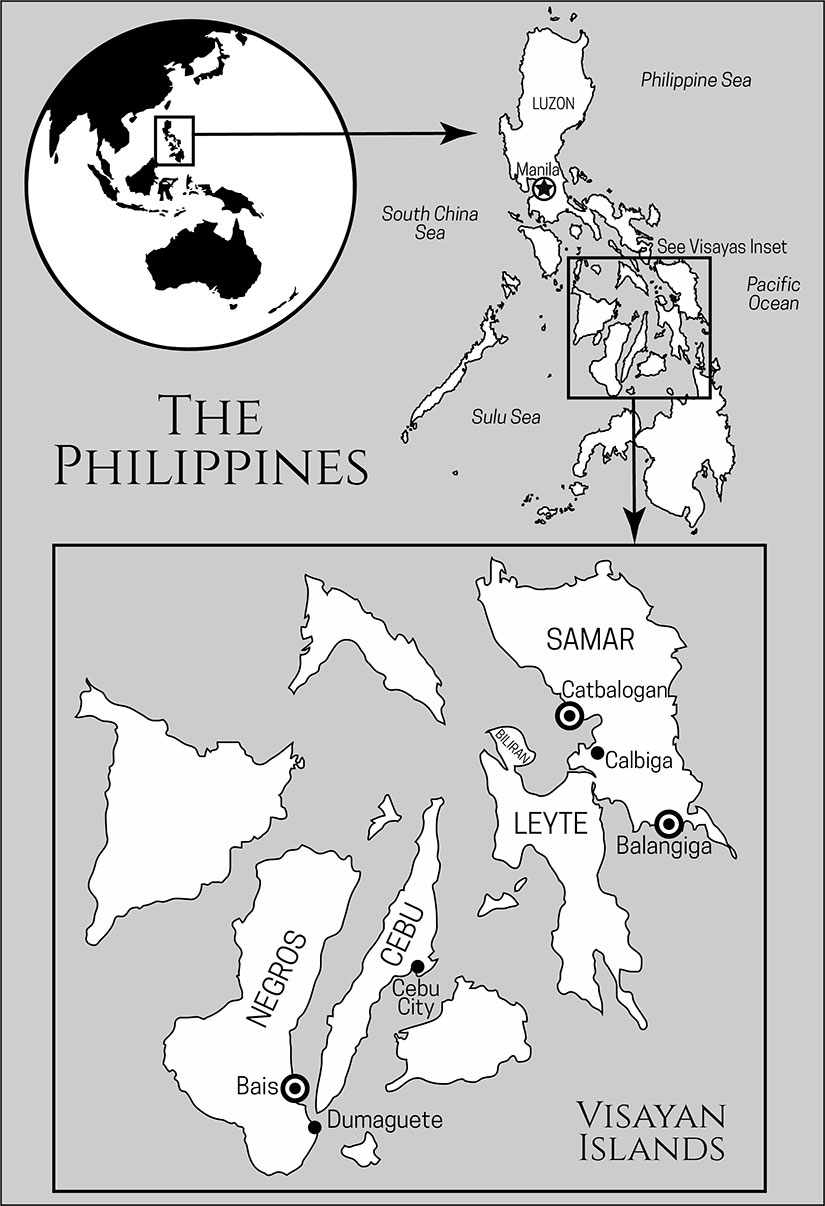

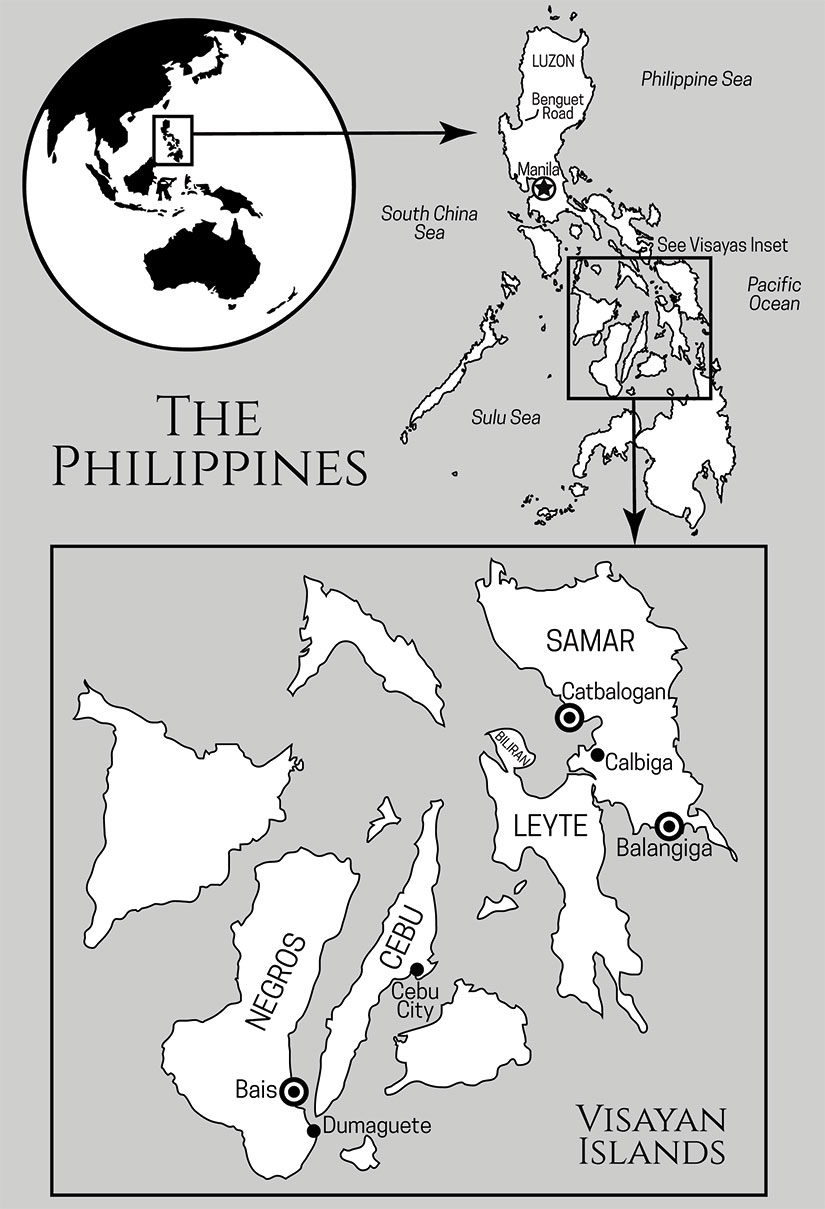

If the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) gets little attention in history classrooms, the subsequent Pulahan War (1903-1907) in Samar and Leyte gets none. But it is the Pulahan War that may have the most parallels to later fights against the Khmer Rouge of Cambodia; the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq; the Abu Sayyaf/Maute group in Marawi, Philippines; Boko Haram in Nigeria; and even the Aum Shinrikyo terrorists, who released sarin gas on a Tokyo subway train in 1995.

The Pulahan War erupted after the Americans captured Samareño guerrilla leader Vicente Lukban in April 1902, and after the Americans declared the Philippine “insurrection” over on July 4, 1902. In other words, it happened after the islands had supposedly been pacified. In reality, the islands were still at war. (The Pulahan War was the largest of its particular type, but it was not the only indigenous, messianic movement in the islands.)

Maybe the Pulahan War is not studied because it was squashed in only four years—a short insurgency compared to the ones the United States has fought more recently. But shouldn’t that be a reason to study it? To find out how American soldiers (and American-trained Filipino soldiers) succeeded so quickly in Samar and Leyte, but cannot outmaneuver the Taliban after nearly two decades in Afghanistan? What really happened out there in the boondocks?

The Pulahans

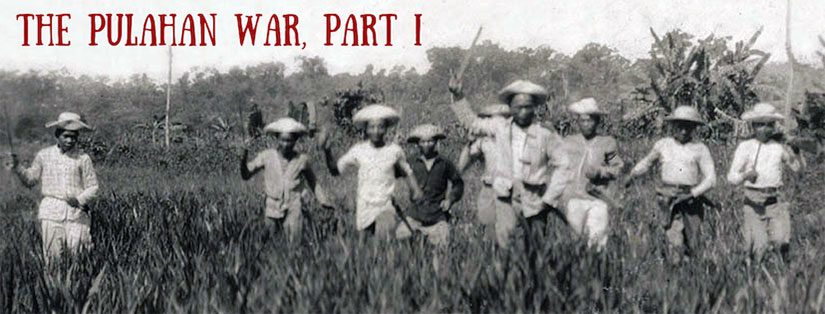

Who are the Pulahans? The name given to them is thought to mean “red pants,” but few of these men actually had enough pants to set aside a pair as a uniform, let alone dye them a specific color. Sometimes they were known to wear red bandanas or other items, but not always. The name could also come from the pulajan, or red, variety of abaca grown by these farmers. The origin of the name “reds” is not what is important about them. What is critical is how they arose: from a specific cauldron of local grievances, traditional values, and foreign interference that so often gives rise to millennial movements.

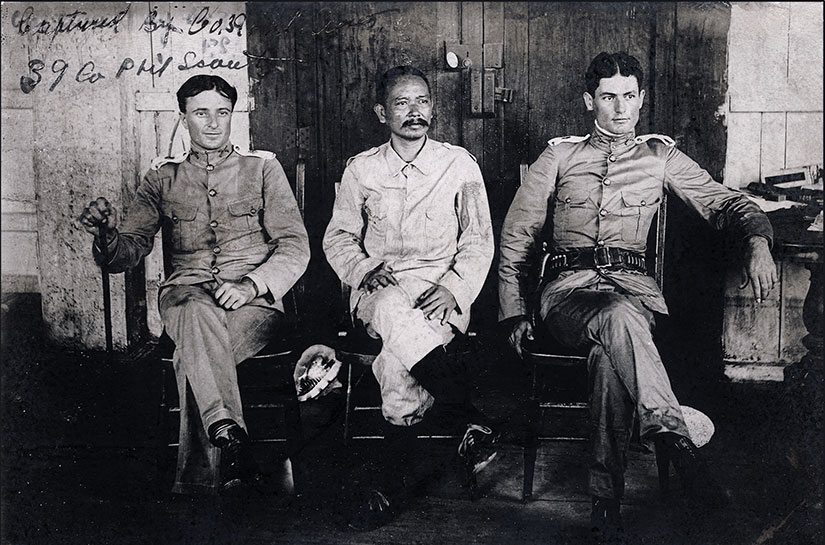

It began with the previous war. In April 1902, the captured revolutionary, Vicente Lukban, negotiated the surrender of the rest of his men: 65 officers, 236 riflemen, and 443 bolomen (wielders of a bolo, or machete-style, knife). These guerrillas brought in 240 guns and 7500 rounds of ammunition, much of which had been pilfered from Company C, Ninth Infantry, at Balangiga (Dumindin). Instead of punishing those who had participated in this attack, the Americans welcomed them in from the jungle. The colonial government even provided cloth, tailors, and sewing machines to outfit the men so they could parade through the capital city Catbalogan in front of the Army brass (Borrinaga, R.O., 20).

This colorful celebration papered over the fact that Samar was a smoking ruin. In his implementation of General Orders No. 100, General Jacob H. “Hell-Roaring Jake” Smith ordered the burning over 79,000 pounds of stored rice and countless rice fields (War Department 1902, 434-51). One American soldier estimated that, by 1902, the island was subsisting on only 25% of a normal yield (Hurley, 55-56). Smith had ordered the destruction of entire villages, and he got his wish: by 1902, 27 of 45 municipalities were in ashes, and of those that remained only 10 had a standing town hall (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Pulahan Movement in Samar,” 245).

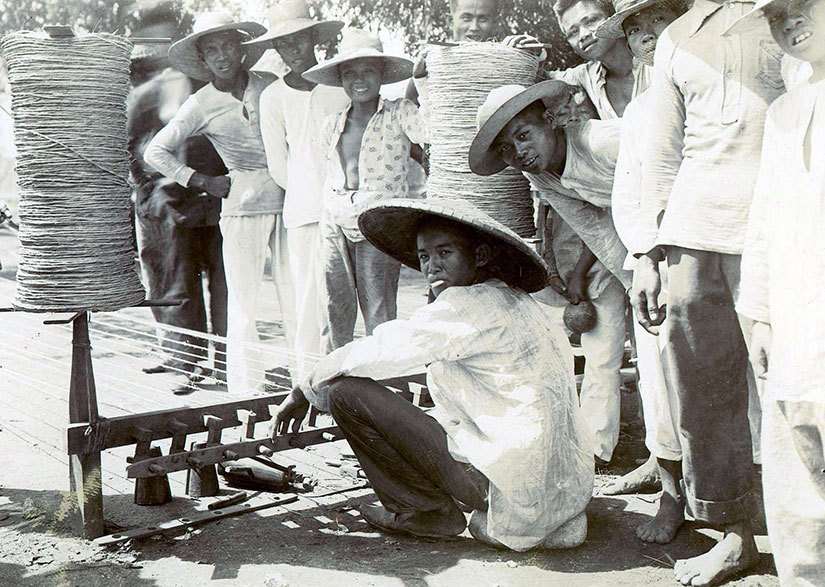

Worst of all, Smith ordered that all captured abaca harvests be destroyed (“Massacre Averted“). Known as “Manila hemp,” abaca is actually a banana plant whose strong fibers can be used as naval cordage, which was in short supply at the time. It was so badly needed by the U.S. Navy and merchant fleets that Congress had made a singular tariff exception for it before the rest of the free trade laws came into effect in 1913. Abaca and coconut products could have been the keystones of Samar and Leyte’s economic recovery, but in 1902 the harvest was, again, only 25% of pre-war levels. To make matters worse, a terrible drought hit Samar immediately after the war ended, from October 1902 to June 1903, so what abaca had not been burned by Smith’s forces was torched by the sun (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Samar,” 245-49).

Even had abaca thrived, the Pulahans would not have gotten rich off the sales. Samar was structured like an island plantation: the growers in the highlands were beholden to the coastal elites. Lowlanders, as they were known, were the ones with ties to foreign merchant houses like Britain’s Smith, Bell, and Company. These elites paid the actual abaca growers less than half the crop was worth, and then they turned around and sold the peasants imported rice at a premium (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Samar,” 257).

Now that the island was “pacified,” the Americans demanded new taxes to pay for their civil government, including a twenty-peso tax on all adult Filipinos (Talde, “The Pulahan Milieu of Samar,” 229-30). The growers did not have twenty pesos—which was US$10 then, or $280 now—so they had to borrow it from the same merchants who had already fleeced them. All they had to stake as collateral was their thousand-peso plots of land. When they could not repay their debts—and the merchants made sure of that—the wealthy townsmen seized title to all they had in the world. To save their families from starvation, or from contracting malnutrition-based diseases like beri-beri, some parents sold off a child at a time to procurers from the big cities (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Samar,” 258-59). These children would become servants, laborers, and prostitutes to pay off their parents’ debts.

The grower had no one to complain to because the elites who had stolen from them were the mayors, police officials, and municipal authorities of Samar and Leyte. In fact, the twenty-peso poll tax that cost the grower his land had been used to pay the mayor’s salary, and you can be sure he was paid before any of the other tax funds were allocated (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Pulahan Movement in Leyte,” 255). If the growers complained, they found themselves held on trumped-up charges until they sold the abaca at the desired rate—or for less. “[American] garrison commanders were both appalled and outraged at the mistreatment they witnessed. The civil officials in particular seemed completely irresponsible, robbing their constituents in the most brazen manner” (Linn, 69).

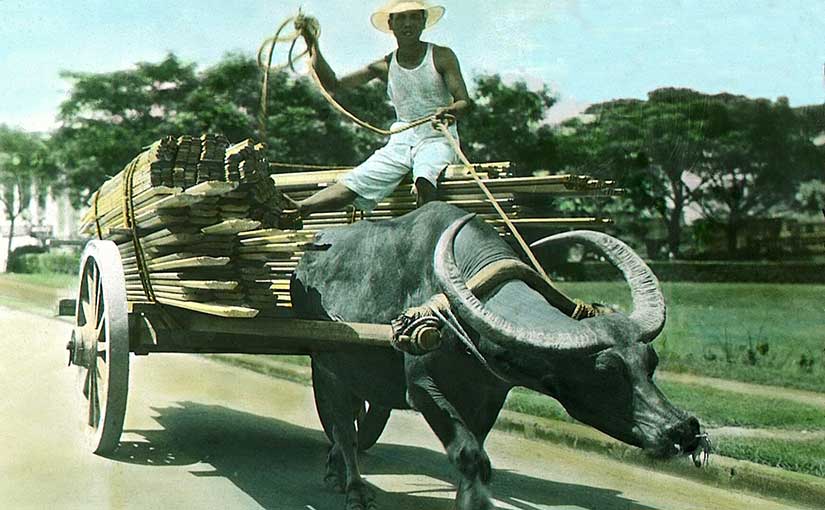

If that was not enough, the 1902 cholera epidemic killed 3175 people in Samar and 4625 in Leyte (War Department 1904, 232). (For Samar, that was about as many as died during General Smith’s “howling wilderness.”) Livestock had also fallen victim to war and disease (specifically, rinderpest). Carabao, or local water buffalo, fell to 10% of their pre-war numbers, according to one contemporary source. The price to replace them went up by a factor of ten (Hurley, 55-56). Because carabaos were essential to plowing and harvesting all crops, their absence meant the starvation that had driven the guerrillas to surrender would continue.

The governor of Samar province, George Curry of New Mexico, knew the peasants were “industrious and hardy people” (Executive Secretary for the Philippine Islands 1906, 584). The problem was that the Americans needed the lowland elites on their side—many of the revolutionaries who had surrendered in April 1902 were these elites, and they were already worming their way into Insular Government positions. The peasants could fall in line with a regime that robbed them blind, or they could look elsewhere. They looked elsewhere.

Specifically, they looked at an old movement for answers to new problems. There had been a messianic group under the Spanish in the late nineteenth century, the “Dios-Dios,” which arose in similar economic conditions as those described above, including both smallpox and cholera epidemics.

At the time, the highlanders thought their illness would be healed by a mass pilgrimage to Catholic shrines to pray for their loved ones’ souls. But the Spanish, thinking this exodus from the mountains was a revolt in the making, attacked the peasants, thus igniting a several-year-long struggle (Couttie). In 1902 this movement resurfaced—or maybe it had never left. Several of the key figures in Lukban’s guerrilla war—the ones who had not surrendered—had been tied to Dios Dios. While under Lukban, the war had not taken on a distinctly religious character, his most die-hard supporters now made fighting Americans a mission from God.

The Pulahans appropriated a specific Dios Dios-brand of Catholic syncretism, similar to the folk tradition of the babaylans (faith healers). The Pulahans called their leaders popes (“Papa Pablo” or “Papa Ablen,” for example), displayed crosses on their clothing or ornaments, and mentioned Jesus and Mary occasionally. They also prayed to living saints, like the “goddess” Benedicta, who, decades before, had led a crowd of 4000 followers up into the mountains to prepare for the coming apocalypse. Benedicta described the coming end of times as a flood that would wipe out the thieving lowlanders while keeping the mountains safe (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Leyte,” 211).

The Pulahans kept this blend of Visayan animist and Roman Catholic practices—all without the hated Spanish friars and priests. In fact, like Benedicta, Pulahan women were often priestesses, especially in the highland farming communes hidden within the jungle. To the Pulahans, this location made perfect sense. These were sacred mountains that symbolized light, redemption, and paradise (Talde, “Pulahan Milieu,” 215). This would be where Independencia, when finally freed from its once-Spanish-now-American box, would fashion a world with “no labor, no jails, and no taxes” (Hurley, 59). Even better, “once they destroyed their enemies, [Papa Ablen] would lead them to a mountain top on which they would find seven churches of gold, all their dead relatives who would be well and happy, and their lost carabao” (Roth, Muddy Glory, 99). In retrospect, it seems impossible for the highland people of Samar and Leyte not to join the Pulahan revolt.

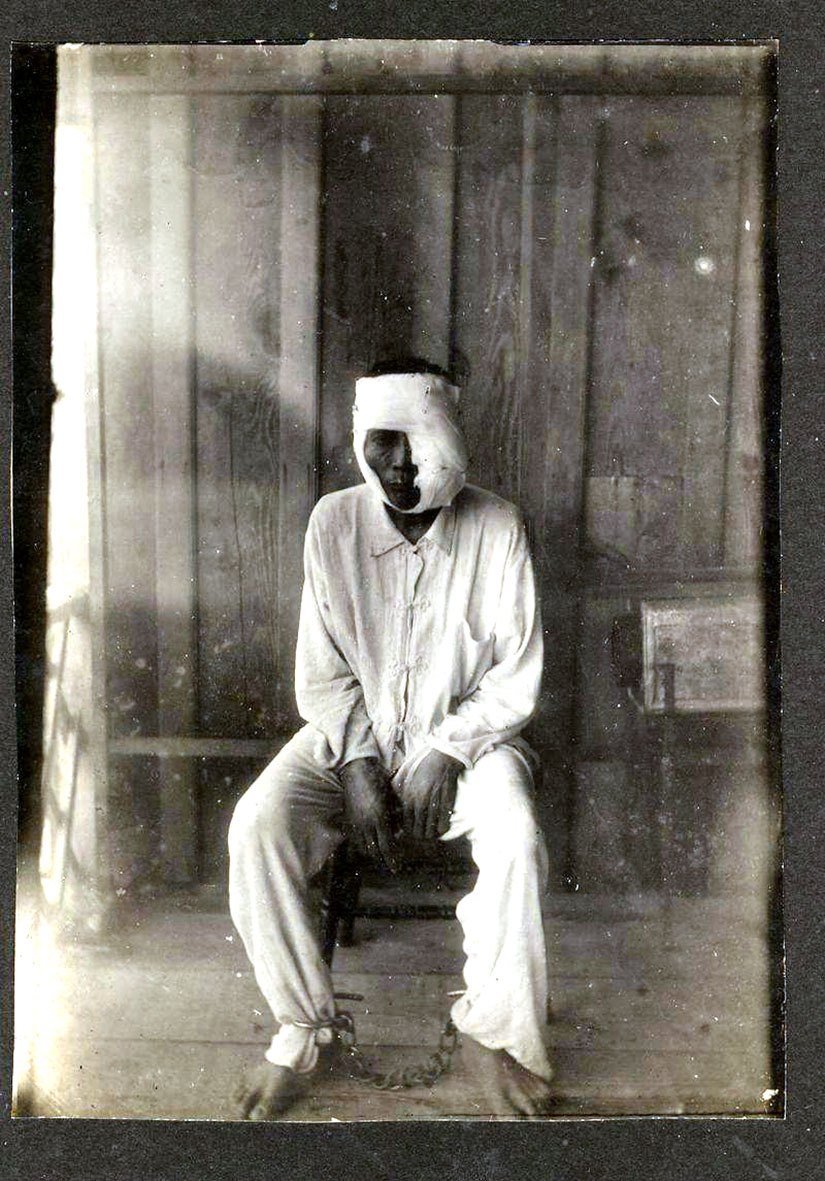

The Pulahan soldiers were a special kind of fierce: they did not cut their hair, did not cut down vegetation while trekking through the jungle, and did not need food or water on their multi-day operations (Talde, “Bruna ‘Bunang’ Fabrigar,” 180-81). They wore special charms, known as anting-antings, made out of anything: cloth, paper, or even carabao horn. Special prayers—composed of pseudo-Latin, local languages, and numerology—offered protection against bullets and bolos. “Should they be shot, which could only happen if they turned their backs, their spirits would return in another person’s body in three days, or if hacked by a bolo, in seven days” (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Leyte,” 230-31). Even better, this reincarnation would deliver the soul to another island. It was a decent way out, given the conditions on Samar and Leyte at the time.

These spells may be quite familiar to China scholars. They sound like the Boxers’ charms—especially the imperviousness to bullets—and there is a good reason for that. Both movements were millennial:

. . . a religious or ideological movement based on the belief in a millennium marking or foreshadowing an era of radical change or an end to the existing world order; especially (a) believing in the imminence or inevitability of a golden age or social or spiritual renewal; utopian; (b) believing in the imminence or inevitability of the end of the world; apocalyptic.

Millennial movements are often caused by rapid economic and cultural change, an increased foreign presence, and natural disasters or war. Samar, Leyte, and China had all these things. Afghanistan did, too. So did Iraq, Syria, Nigeria, Cambodia, and more. Like all these countries, the Pulahans believed salvation would be theirs eventually, even if they would have to help God along a bit. When the righteous flood finally came, the Pulahans would be on their Monte de Pobres (Mountain of the Poor), the “surest and safest place” in the islands (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Leyte,” 211). From there they could establish a perfect Samareño kingdom on earth, free from Spanish, American, Chinese, and mercantile interests.

Only it did not go quite like that. Read more on the Pulahan War in part two.

[Featured image was taken by and of members of the 39th Philippine Scouts dressed in captured Pulahan uniforms and carrying captured bolos. Multiply these men by several dozen, at least, to get the full effect of a Pulahan charge. Photo scanned by Scott Slaten.]

Have you heard romantic stories of evenings strolling on the

Have you heard romantic stories of evenings strolling on the

It was supposed to cost

It was supposed to cost