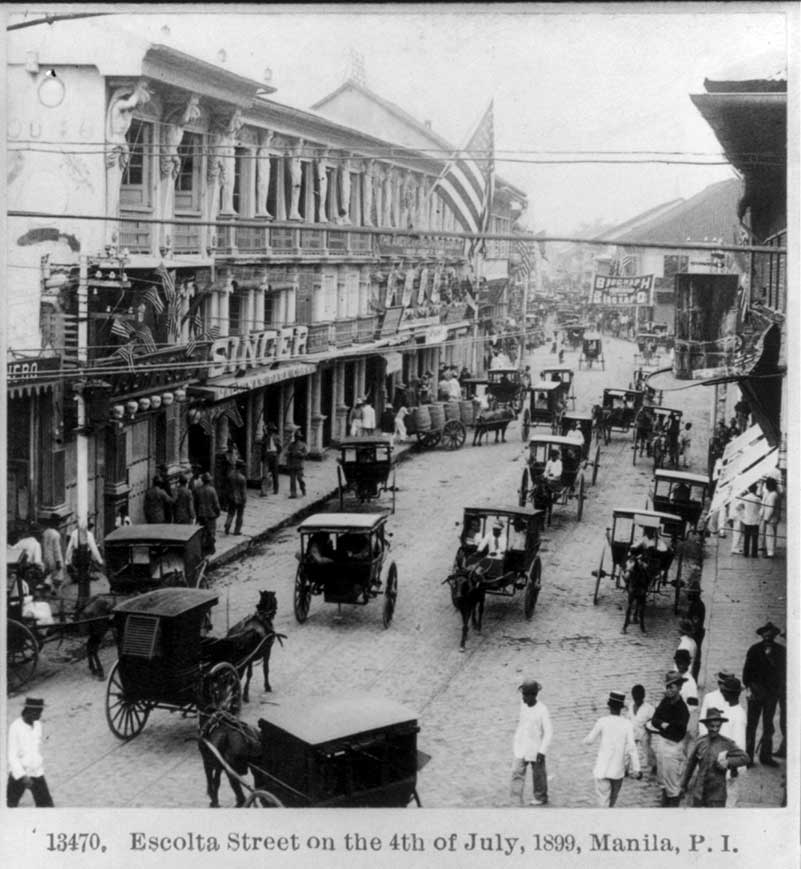

Wealthy doñas, notoriously late risers, would bathe and dress just in time to catch the evening breeze that cooled the bay and blew away the mosquitos. Once there, they would catch up on the latest tsismis, gossip passed from calesa to calesa like a tattler’s telegraph. Then they would be off to eat and dance at a friend’s house, returning home shortly before dawn to sleep through another morning. Meanwhile, their servants ran their households, farms, and shops.

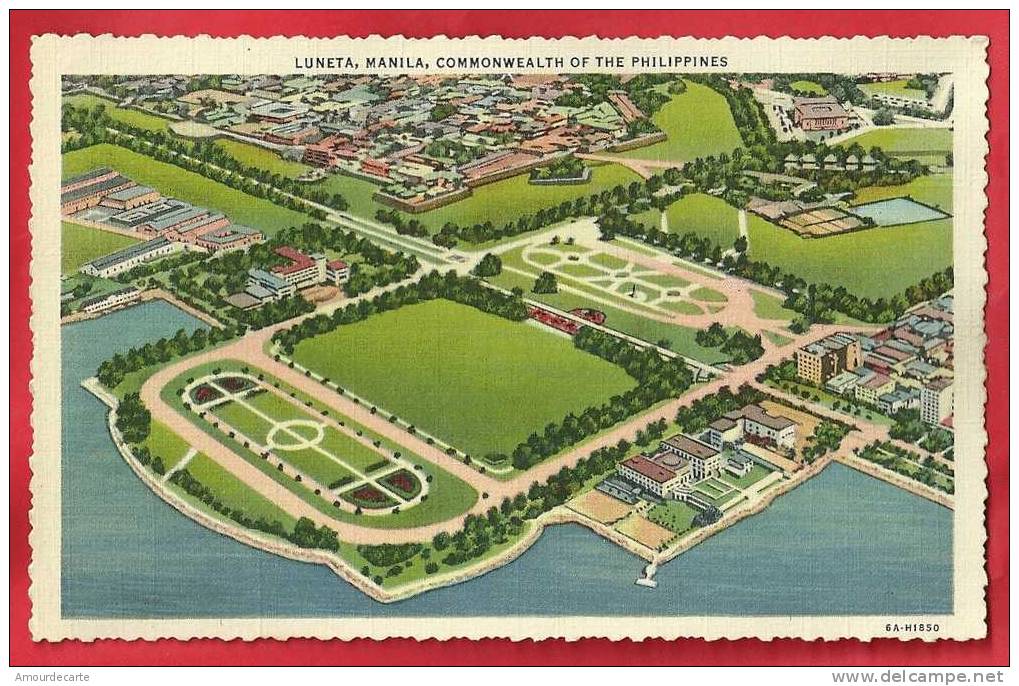

Javier’s carriage got in line with the others circling in comfort, leaving the poor to walk the shoreline. Calling the Luneta a park was a bit generous, considering the utter lack of trees or foliage. The only decorations were incandescent gas lanterns circling the perimeter, sort of like candles on a vast birthday cake.

Called the “Champs-Elysées of the Philippines” by a French physician in the early nineteenth century, Luneta Park was also dubbed “the favorite drive of the wealthy [and] the favorite walk of the poor people.”

There were three good reasons for this. First, as one American wrote: “The sunsets from the Luneta have been more than pyrotechnic, and I now believe that nowhere do you see such displays of color as in the Orient, Land of the Sunrise.” Troubling Orientalist fetish aside, I think he’s right. And the sunsets may have actually gotten better with pollution, as long as you like the color red. Hey, don’t blame me—Scientific American actually agrees.

The second and third reasons for the popularity of the Luneta come from Edith Moses, wife of one of the first Philippine commissioners: “There is always a breeze and there are no mosquitoes; besides that, one meets everyone he knows, and ladies visit in each other’s carriages in an informal way….There is the comfort of dispensing with hat and gloves, and many ladies and almost all young girls drive in low-necked dinner or evening dresses.” It boils down to (2) no mosquitos and (3) a serious party.

If the Luneta was the place to be, naturally it was where Javier took Georgina on their first “date,” though she did not realize that’s what it was. He’s a sly dog, that Javier. He’s also part Spanish, and the Spanish were the first to ritualize visits at the Luneta, including the rules of the road, prompting Georgina to ask:

“What would happen if we turned the carriage around and circled in the other direction?”

Javier laughed. “You are a rebel, Maestra.”

“No, really,” she urged on. “This whole orderly migration—I just can’t reconcile it with the chaos of the rest of the city.”

“That’s why the Spanish liked it,” he answered. “Only the archbishop and governor-generals’ carriages were allowed to pass against the line. That way you had no excuse but to recognize and salute them as they passed.”

“You could get in trouble for forgetting?”

“Absolutely. The Peninsulares believed it important to punish people for small sins lest they attempt any larger ones. It’s not an uncommon assumption among occupiers.”

Ouch. Javier was not a huge fan of the newly-arrived Americans, as most readers know, which is why of course he was destined to fall in love with one. But he had a point: the Yankees ultimately ruined a good thing.

Maybe it was because the Luneta was not grand enough for them. The wife of Governor William Howard Taft was underwhelmed at first:

“And now we come to the far-famed Luneta,’ said Mr. Taft, quite proudly.

“Where?” I asked. I had heard much of the Luneta and expected it to be a beautiful spot.

“Why, here. You’re on it now,” he replied. An oval drive, with a bandstand inside at either end—not unlike a half-mile race track—in an open space on the bay shore; glaringly open. Not a tree; not a sprig of anything except a few patches of unhappy looking grass. There were a few dusty benches around the bandstands, nothing else—and all burning in the white glare of the noonday sun.

While Helen Taft did eventually warm to this “unique and very delightful institution,” it was not love at first sight. She was not the only one, either. One American wrote a letter back to her friend in Scranton, Pennsylvania, which the friend sought fit to publish in the local Republican newspaper: “The Luneta is crowded every afternoon with officers dressed in spotless white from their heads to their heels driving fast horses and flirting with other men’s wives. The husbands, as a rule, are at the front and only get in occasionally, tired out and dirty, and it makes me sick.” Some Americans certainly brought their puritanical brand of Protestantism with them.

What harm in a bit of flirting? There had always been a social side to what went on at the park—innocent courtship right under the friars’ and nuns’ noses—which is why the place was an early favorite of my character Allegra. And officers flirting was common enough that it was captured in this awesome 1899 Harper’s Weekly centerfold, of which an original hangs in my dining room (because eBay makes such delights possible).

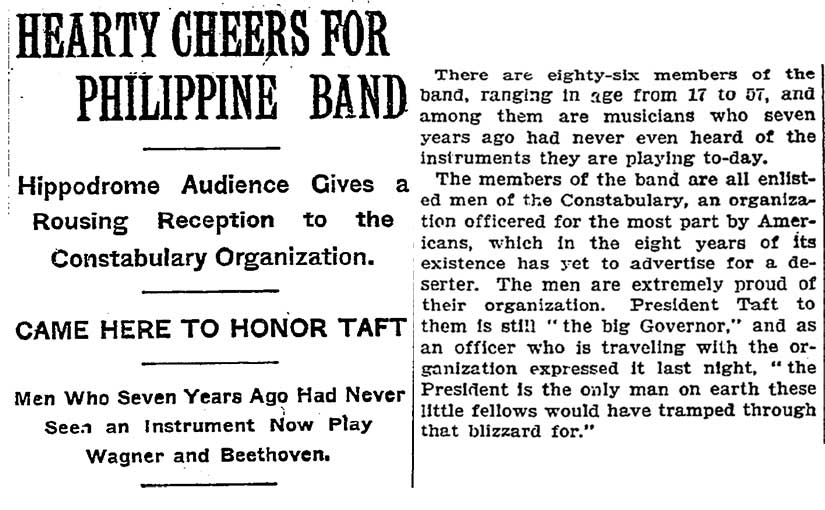

There seems to have always been music at the Luneta—small bands were ubiquitous in the islands, and every village had at least one—but the Americans congratulated themselves for adding the Philippine Constabulary Band to the regular roster. These musicians, led by African American conductor Lt. Walter H. Loving, were widely noted for their excellence. They not only traveled to St. Louis for the 1904 World’s Fair, but they were also invited to play at President Taft’s 1909 inauguration.

One of the Constabulary Band’s favorite numbers was one Americans would still recognize, as it is played by modern university marching bands at football games:

“Hey, that’s ‘Hot Time in the Old Town,’” Georgina exclaimed. “How’d they learn American music?”

“The ‘Hototay’ we call it,” Allegra said. She sat between Javier and Georgina, but she was too tiny to be much of a barrier. “The song is everywhere, even funerals. Filipinos think it is your national anthem.”

Georgina laughed. “Maybe it should become yours.”

“You suggest we adopt the drinking song of an occupying army?” Even before Javier finished the question, he regretted asking it. Hay sus, why couldn’t he keep his mouth shut?

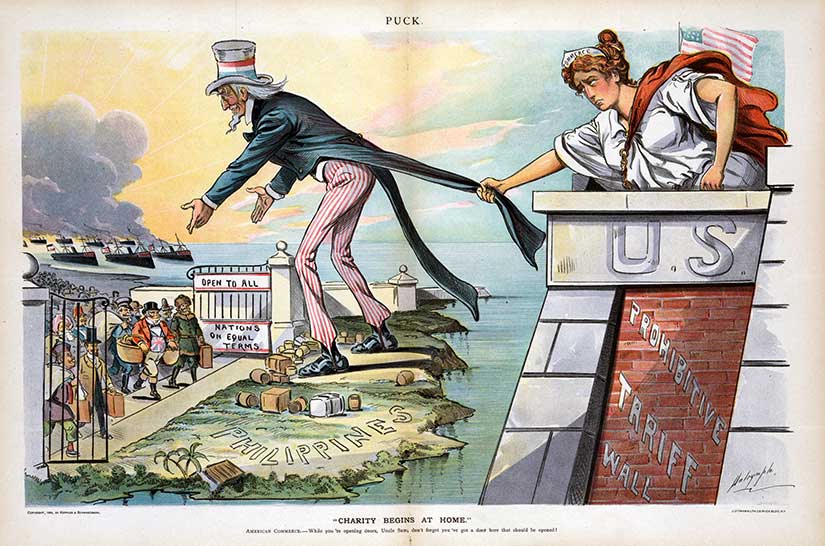

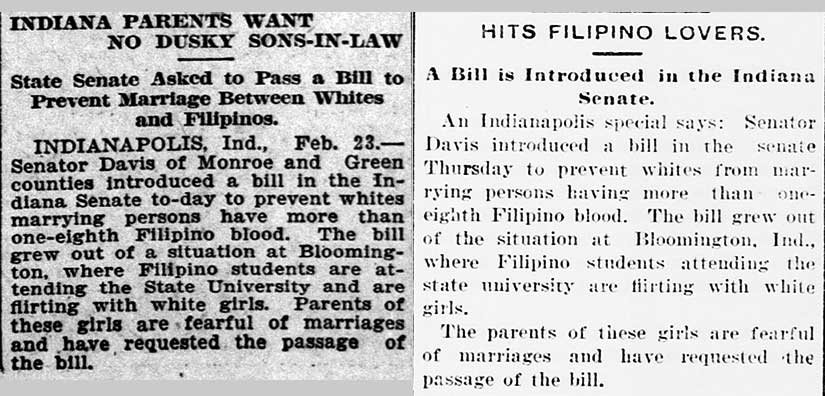

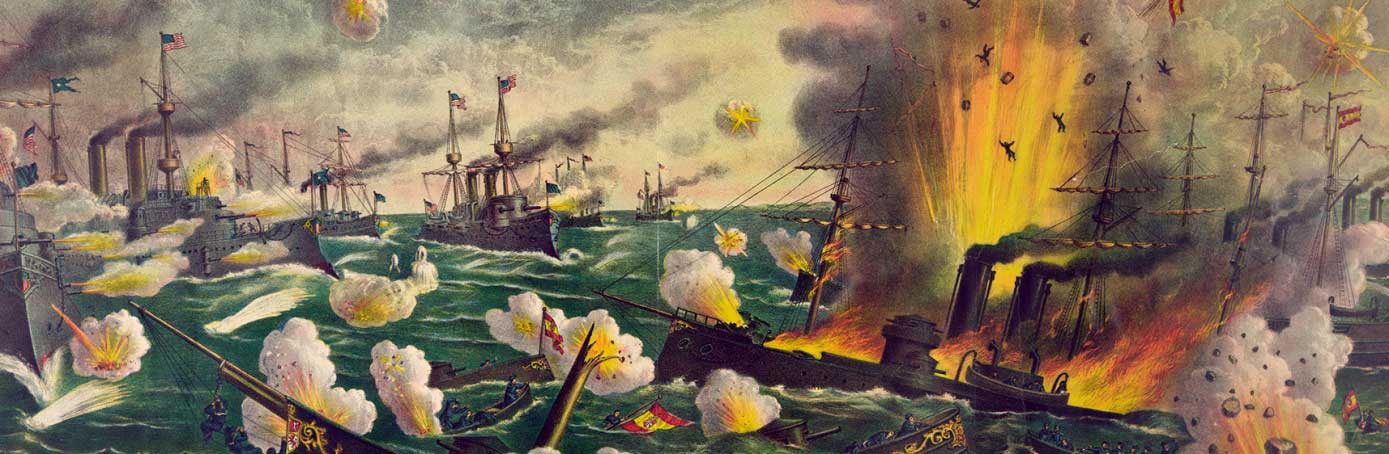

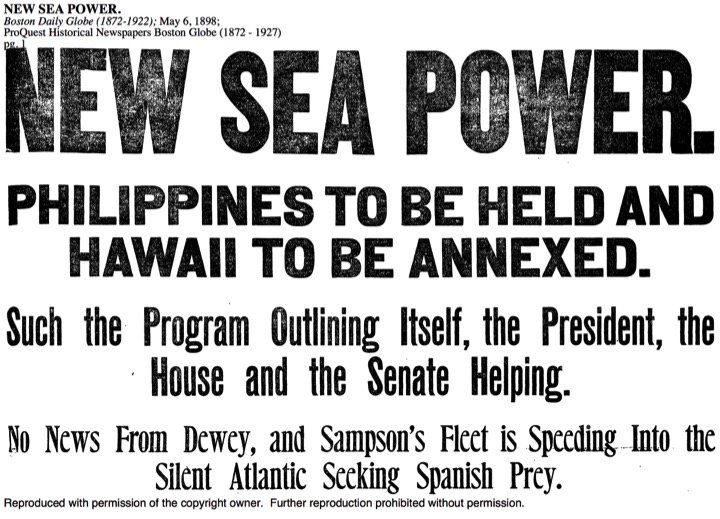

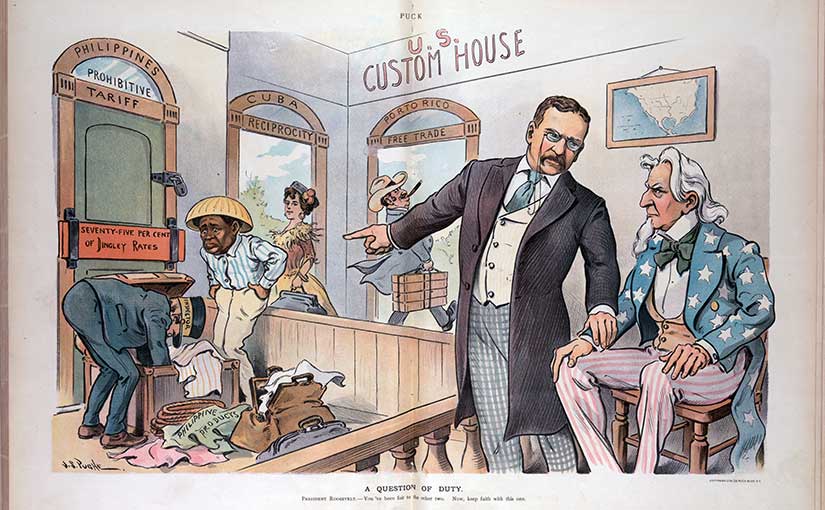

Maybe Javier was a bit sensitive, but Georgina certainly did arrive in the Philippines with the “benevolent assimilation” bias of the other Insulares and Thomasites, though she will take her mission to an interesting and sexy extreme. Though it is important to point out that even at the beginning, she was not hateful. Many were. Take the author of those 1900 letters published in the Scranton Republican, who said: “As soon as the concert is over, ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ is played…Every soldier and sailor and all the Filipinos (deceitful wretches) stand with uncovered heads until the last strains die away….” Manila was still a field of battle in the Philippine-American War, true, but this author failed to realize that the Americans were the Redcoats here, not the patriots!

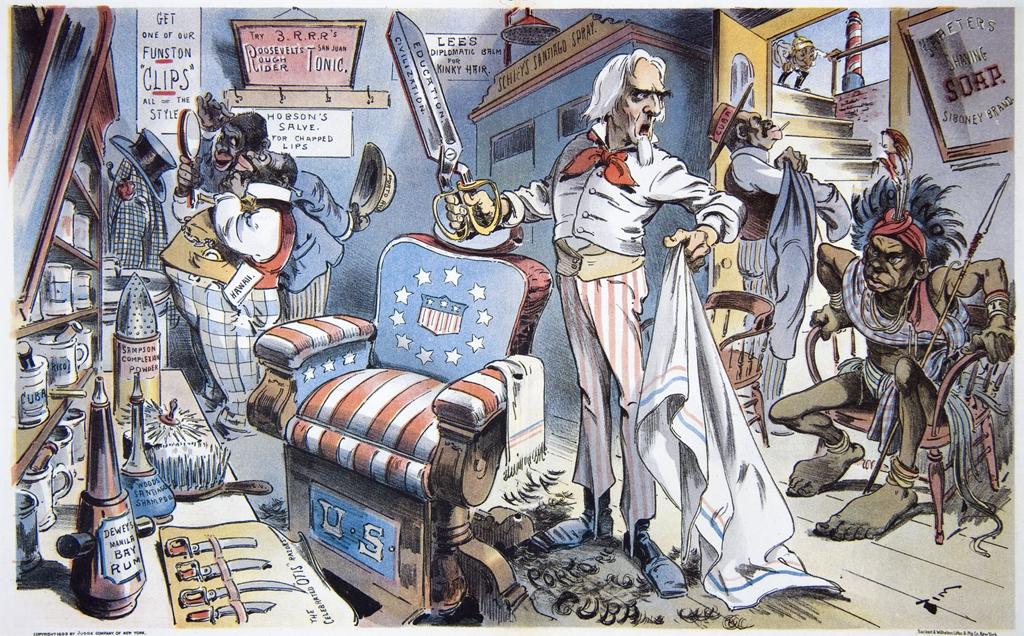

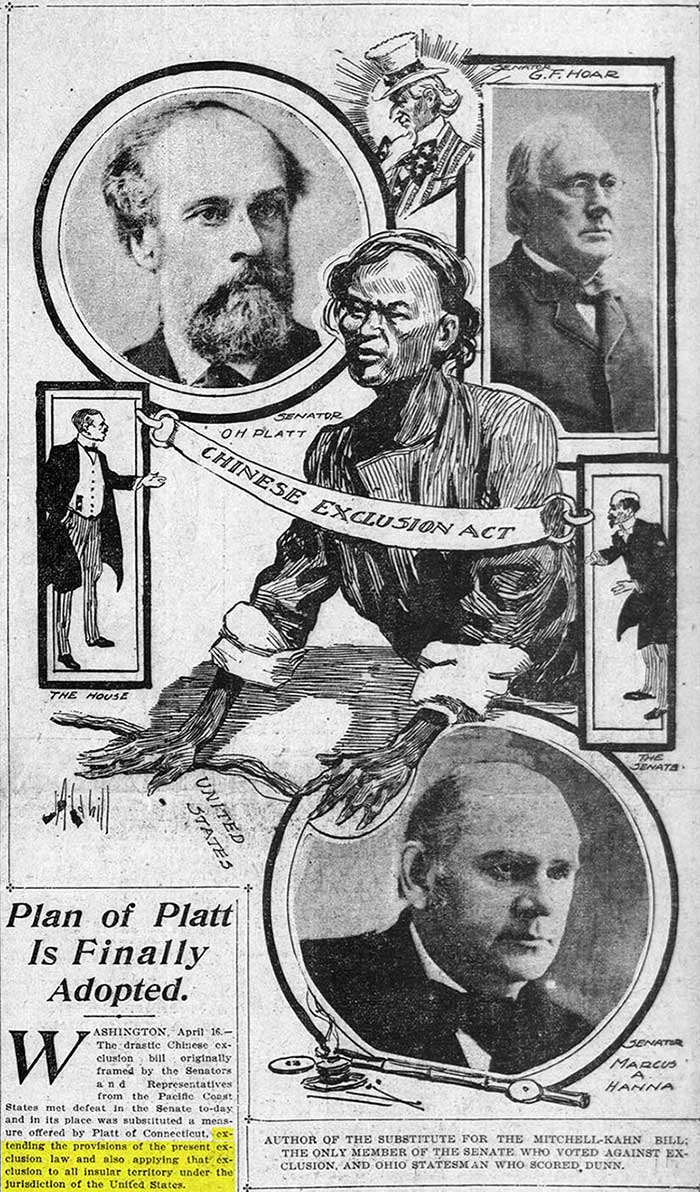

As an aside, my husband gave me a huge coffee table book from 1899 entitled Our Islands and Their People—a threatening premise, as if “their people” are infesting “our islands,” and how dare they! The text of the book is pretty neutral, and the photographs themselves beautiful, but the captions are outrageous. You can read more on the racism of the day here.

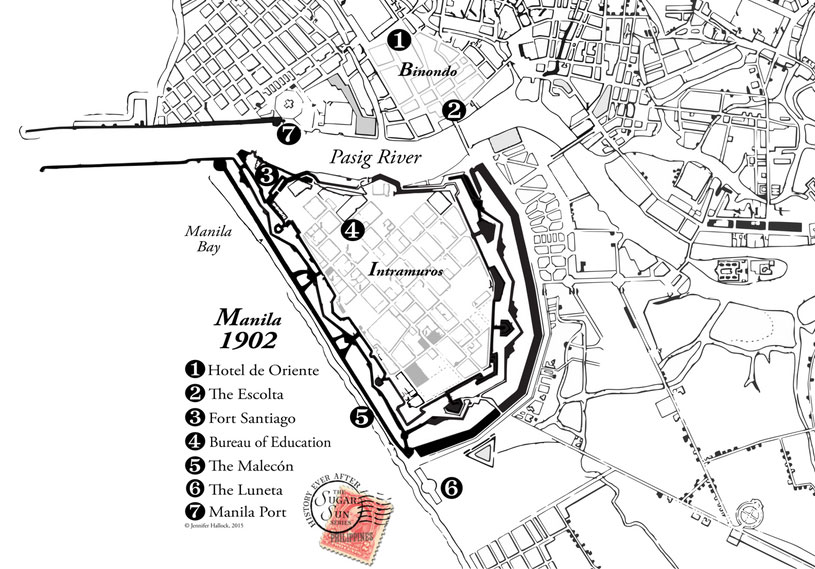

The Americans believed that they were improving the islands, but they did not improve the Luneta. In fact, they may have ruined it. If you have been the Luneta, you are probably confused by everything written above because the main body of the park is most definitely not along the shoreline—not anymore. In the construction of the port of Manila in 1909, the Americans reclaimed 60 hectares of land, the first of many expansions.

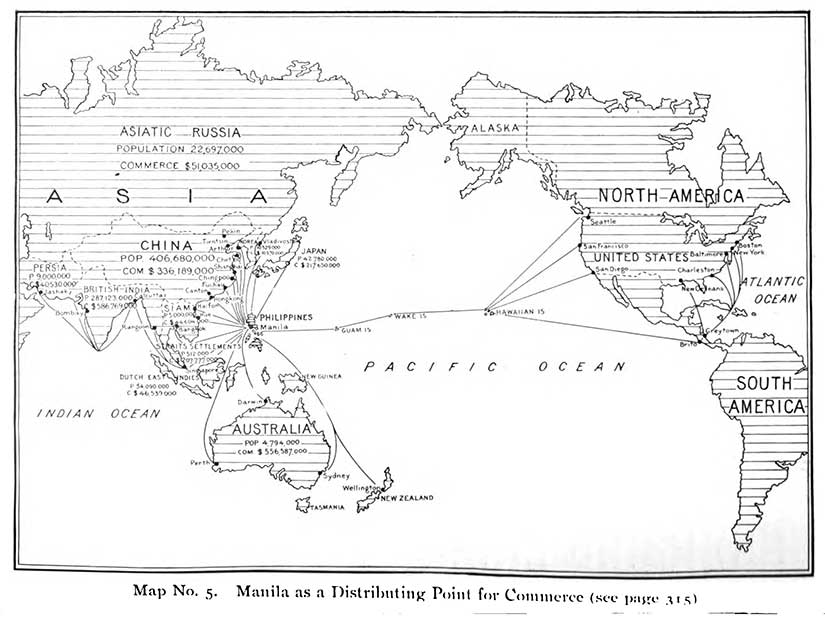

By 1913, a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle wrote: “Today the Luneta remains as it was in the old Spanish days, but its chief charm, the seaward view, is gone. This is due to the filling in of the harbor front, which has left the Luneta a quarter of a mile from the waterfront.” On their new land, the Americans built a “Gringo Luneta,” in the words of Nick Joaquin, and it was here that they eventually put their own exclusive social clubs, like the Elks Club, the Army and Navy Club, and the Manila Hotel—all gated or indoor establishments. They managed to keep the seaside space for themselves and relegate the poor and non-white to their own homes. Shame—especially since Mrs. Taft brought the idea of the Luneta back to Washington D.C. with the rededication of the Potomac Drive. Don’t ruin the original and then rebuild it halfway across the world.

One thing that hasn’t changed in Manila since 1900 is the traffic. The anonymous visitor who called the Filipinos “deceitful wretches” also said about the end of the evening: “there is a crack of the whip and a grand hurrah and one mad dash for the different homes. I wonder there are not dozen smash-ups each afternoon, but there are not. I used to melt and close my eyes, expecting to be dashed into eternity any moment, but I have learned to like it, and I don’t want anyone to pass me on the road.” We’ve all been there.

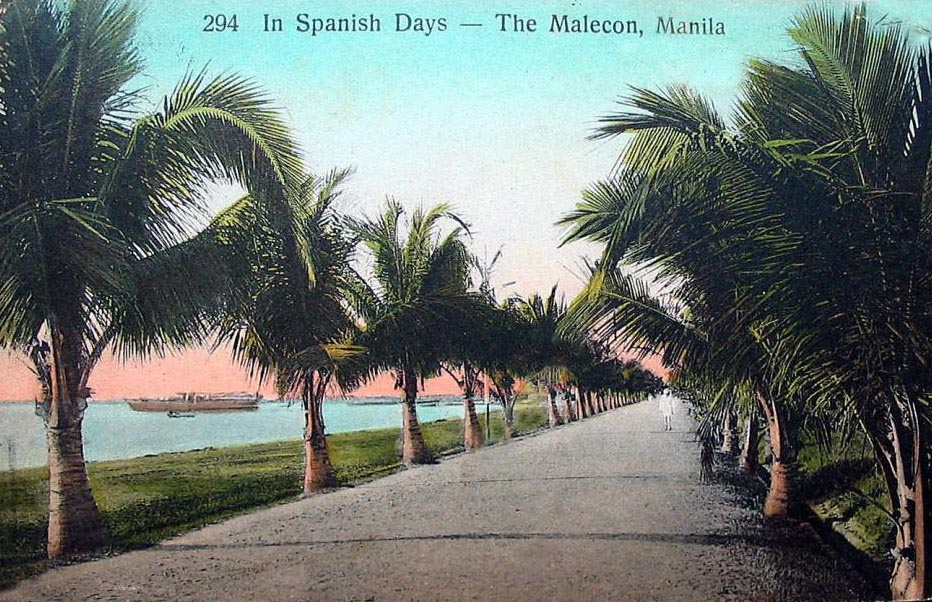

Some park goers did not wait for the end of the evening to race, though. With the old shoreline, the water went right up to the walls of Fort Santiago—or almost. There was a single open road there, called the Malecón, where carriages practically flew:

The two vehicles ate up the open road. Georgie did not consider herself a coward, but she was torn between fearing for the horses’ safety and for her own. Maybe sensing that, Javier put his arm around her shoulders, pulling her closer to his side. It was too cozy by half, but it steadied her enough to make the frenetic motion bearable.

The two nags kept changing the lead. One would break out in a small burst of speed, and then slow in recovery while the other made his move. They had at least a mile to go until the “finish” at Fort Santiago, and it seemed that Georgie’s original prediction was on the mark: the sole surviving animal would win. It was less a race than a gladiatorial bout. Unfortunately, their own horse showed signs of exhaustion first, probably because he pulled an extra passenger. His movements became choppy. His head drifted to the side, and he kept jerking it forward, again and again, as if the motion could create the winning momentum.

With every spasm of the horse’s head, the carriage jolted. Soon, the frame on Georgie’s side started shaking. The roof above them was supported by three thin pieces of bamboo, and she watched one pull out of its fastener. The front corner of fabric flapped wildly in the wind, pulling hard at the other two rods. Even more worrisome was the squeak of the wooden wheel to her left. If that splintered, the whole apparatus would collapse, probably pulling the two men and the horse right on top of her. The sound of hooves, wind, and screaming jockeys drowned out Georgie’s increasingly frantic warnings.

Or so she thought.

Javier tapped the driver’s shoulder. Hard. When the man didn’t respond, he grabbed the fellow’s arm and shouted. The driver argued back, probably insisting his animal could still win. Javier glanced over at Georgie briefly and added something in Spanish about “the lady.” He signaled again, this time his face quite stern. Javier’s scowl was, no doubt, the most effective weapon he had.

Georgie was grateful. They were finally slowing down. “The carriage is falling apart,” she tried to explain when she could finally be heard over the din.

“I know,” Javier said in quick English, peering over her lap to the wheel beneath. “We’ll make it, don’t worry. But I blamed quitting on you, so act like you might swoon.”

Georgie fanned herself wildly with her hand and threw back her head. Was that right? She had never before tried to feign fragility—it was not a safe thing to do in South Boston.

Javier watched her for a second, an unreadable expression on his face. Then he laughed—at her this time, not with her. “Wow, you do that badly.”

She gave him a little swat on the arm. “What a terrible thing to say.”

One eyebrow rose. “I don’t think so. I dislike weak women.”

“Then why put on a charade for the driver?”

Javier glanced up at the disappointed Filipino. “So he and his horse wouldn’t lose face. Honor matters even for a Manila cabbie, so I thought a little play-acting from you would be an easy solution. Now I’m not so sure.”

Georgie did not like her competency questioned, even in such a ridiculous arena. “I had no idea that theater was required. How convincing does this have to be?”

He looked at her intently. “Very.”

She slumped back in the seat, trying again to look helpless.

“Ridiculous,” Javier murmured under his breath as he reached out to her. Before she could react, he pulled her close, tucking her right shoulder under his arm and pressing her solidly against his chest. He gently brushed her cheek with his fingertips, the way one might soothe a skittish child. Up until that moment, Georgie had only pretended to faint; now she actually felt light-headed.

“Are you okay, mi cariño?” His words played to the driver, but they felt genuine enough to her.

She looked up. This close, she could see honey-colored circles in his brown irises. They looked like rings on a tree. Did she see in them the same fire she felt, or was this a part of the show?

Gently Javier tilted her chin up, his lips now inches away. No one had ever tried to kiss her, not even Archie–his amorous attentions had all been by pen. She thought about resisting, but that was all it was, a thought. Javier’s breath was clean. Only the smallest bite of scotch lingered from lunch. Given her past, Georgie had never believed alcohol could be an aphrodisiac, but on this man the crisp scent was provocative. He smelled of confidence and power, yet his lips looked surprisingly soft—

Ha ha, I think I’m going to leave it there. You’re welcome.