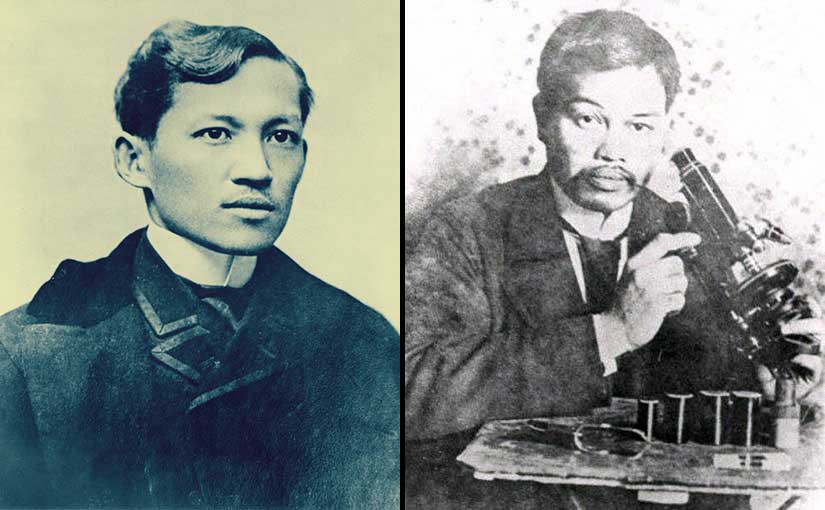

Here’s the thing about imperialism: every major colonial power sowed the seeds of its own destruction. How? Unwilling to do all the work of running a colony themselves, they sent the best and brightest of every generation off to be educated, sometimes in the home capital itself. Thus, Mohandas Gandhi studied law in London, and even scrappy Ho Chi Minh learned about communism while doing odd jobs in Paris. José Rizal and Antonio Luna, among others, were educated in Spain. Though we may consider these men elites, they often were of middle-class backgrounds. Like the liberal bourgeoisie of Europe, what made the ilustrados different was their education.

I don’t know you, but I do know that Rizal was smarter than either you or me. He was conversant in at least 11 languages and could translate another 7. He was an ophthalmologist by training and a patriotic novelist by necessity. And then there’s Luna. In addition to arguably being the greatest Filipino general of the Philippine-American War, Luna was also a widely respected epidemiologist and had a PhD in chemistry.

In Europe, these “enlightened ones” were taught the principals of liberal constitutions—rights that we take for granted, such as the freedoms to assemble, speak freely, practice a chosen religion, and have due process of law. All they asked was that these rights apply to the people of the colonies, too. Gandhi, Ho, and Rizal all wanted equality before they wanted independence. When the Europeans would not give it, their hypocrisy was obvious. Though Asian nations did not fully break away until after World War II, the seeds of revolution were planted at the turn of the 20th century with the ilustrados. (Featured image of ilustrados in 1890 Madrid.)