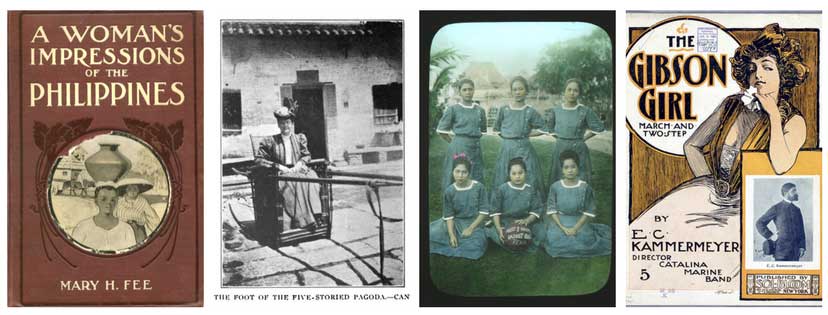

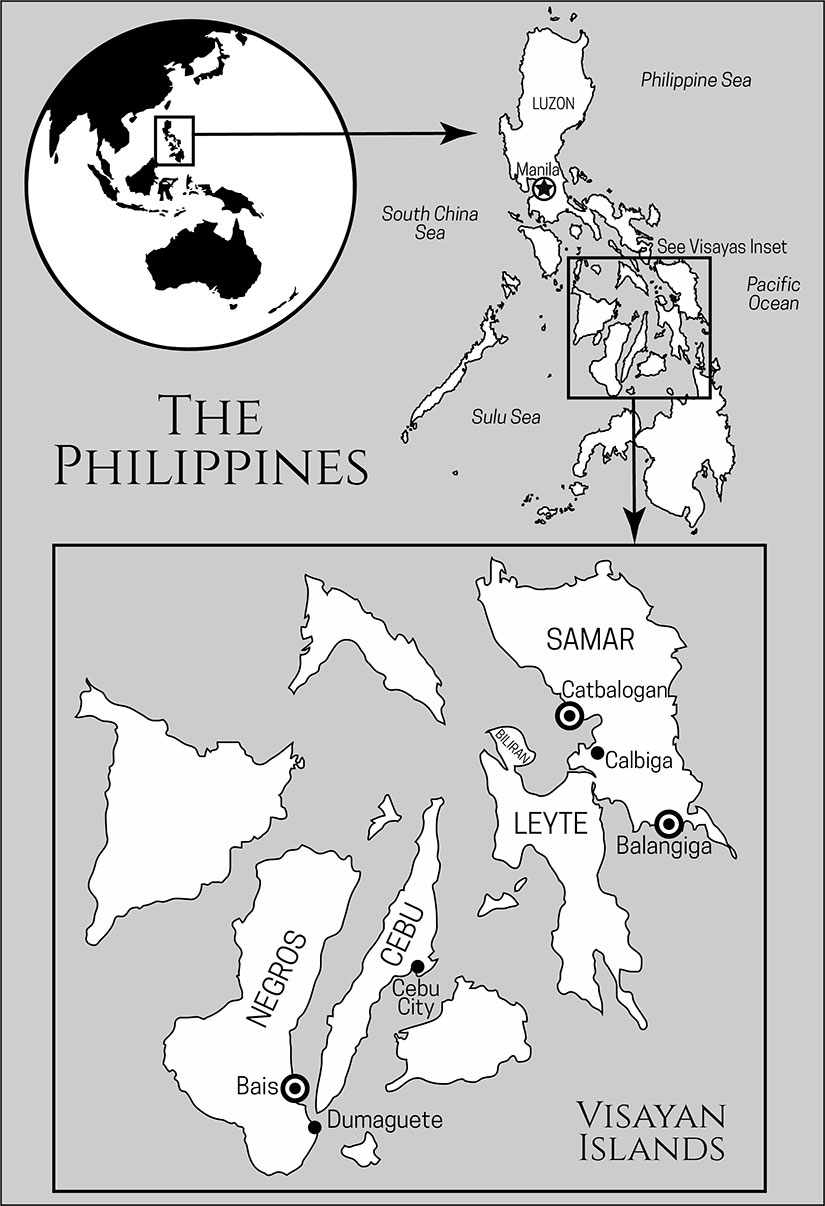

My upcoming book, Sugar Moon, will be firmly rooted in history that I believe every American should know: the ambush of a company of American soldiers on September 28, 1901, in Balangiga, Philippines. Far worse was the American counterattack on the entire island of Samar. Most people have never heard of either. What happened that day in Balangiga—and in the months afterward—has been overshadowed by other towns that Americans do know, ones with names like My Lai and Fallujah. Had we learned the lesson of Balangiga, though, these two towns in Vietnam and Iraq might never have hit the headlines. In fact, they might not be noteworthy at all.

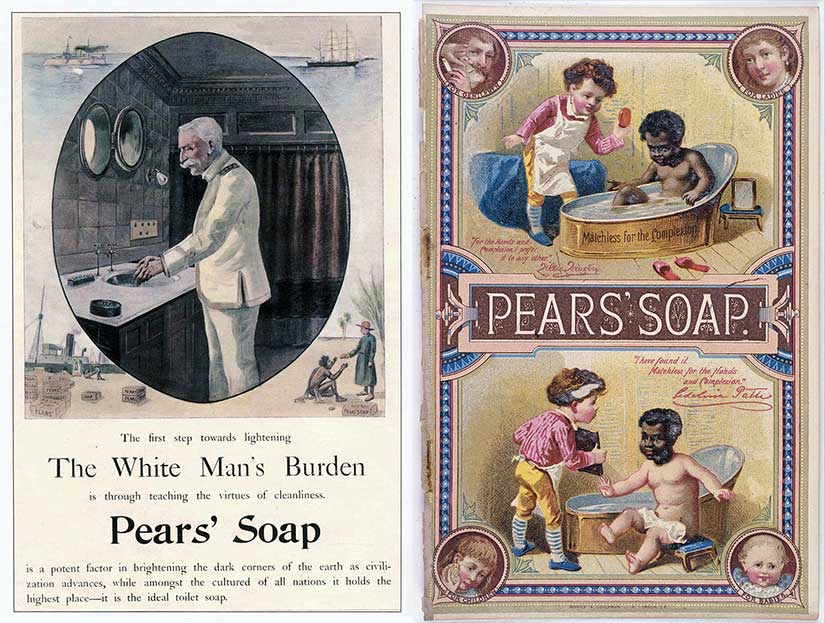

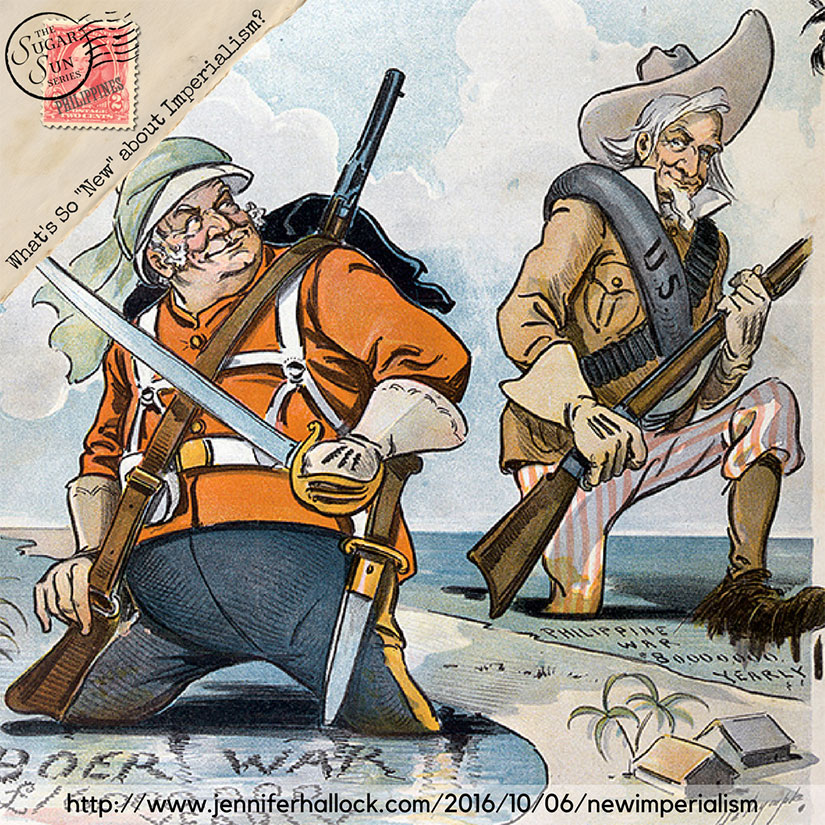

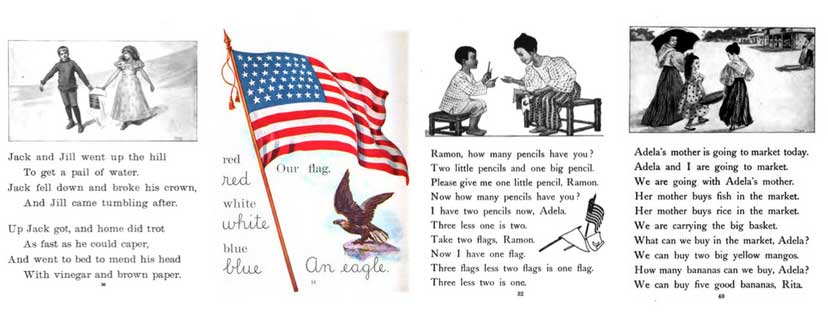

Company C occupied this town, and occupation is ugly. It doesn’t matter how you justify it—in this case, blockading the southern coast of Samar so that the guerrillas in the mountains could not be resupplied, a legitimate military purpose. It also doesn’t matter if the occupation starts off peacefully, which it did in Balangiga. It is not going to stay that way. The lesson of occupation throughout world history—no matter whether we are talking about ancient Greek occupation of Jerusalem, Israeli occupation of Lebanon, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, or the American occupation of the Philippines—things will go downhill. People will suffer.

The Americans called the Filipino guerrillas insurrectionists, and they labeled what happened in Balangiga a massacre, implying that the perpetrators had no just cause. On the other side, Filipinos call their soldiers revolutionaries, and they see the event itself as a just uprising. If you want to avoid all judgment, it was an incident, encounter, or more specifically an ambush. The key question is why? What had happened in that town in the month of September 1901?

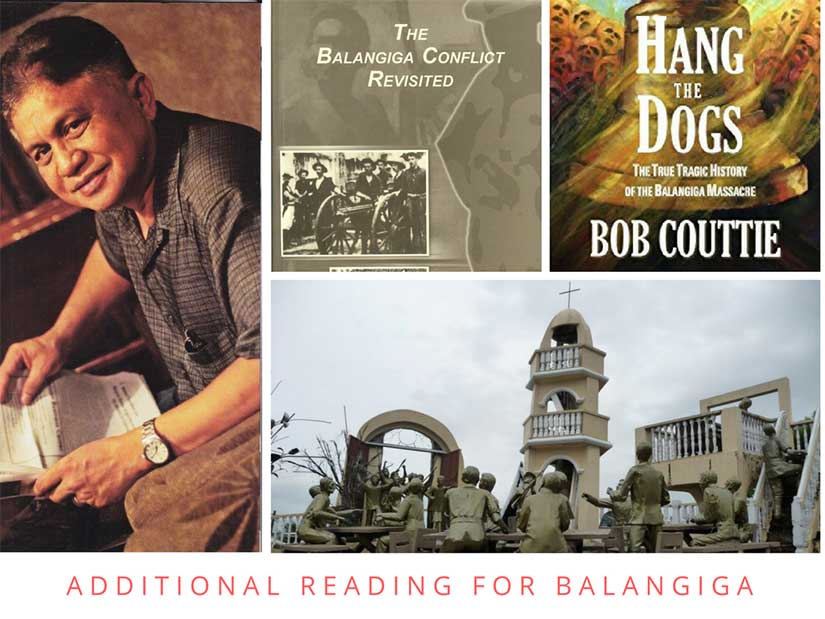

I am greatly indebted to Philippine historian Rolando O. Borrinaga and British writer Bob Couttie for their first-hand research and outstanding work on Balangiga. In my version of the story, I have taken some liberties—merging characters to simplify things for the reader, renaming a few people—but I hope that my unwitting mentors will find that I got the big brush strokes right. All errors are my own, of course.

Relations between Filipinos and the American garrison did not start worse than anywhere else. An American officer played chess with the parish priest. One sergeant studied martial arts with the police chief. The townspeople were in an impossible situation. If they became too friendly with the Americans, they would face retribution from the revolutionaries up in the mountains. If they resisted American rules, the yanks would start to limit normal activity in the town. So the people of Balangiga tried to play it cool, stay neutral.

But the Americans noticed some strange things happening—like sweet potatoes planted in the jungle for the guerrilla soldiers, or townspeople not cutting down banana trees that could provide the guerrillas cover—and they thought they had been betrayed. They ordered the town to cut down essential food sources, to “clean up” the town. But if the town complied, not only would they need to destroy their own property, they would also endanger the understanding they had with guerrillas. I think you probably see where this is going. The reality of a town like this during occupation is that it will be caught in between two armies, and if neither army can truly protect the civilians against the other, the people must try to play one off the other. It is a dangerous game, and an ironic one to be imposed by a country whose own origin narrative of speaks of uprooting imperial oppression. The Patriots had become the Redcoats.

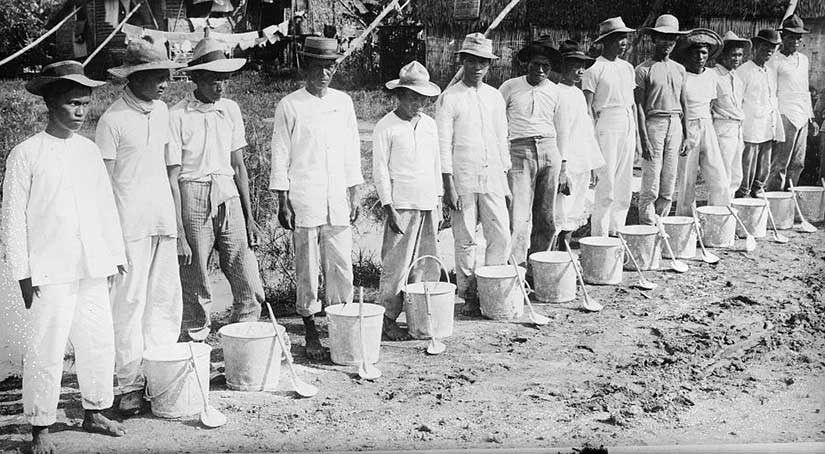

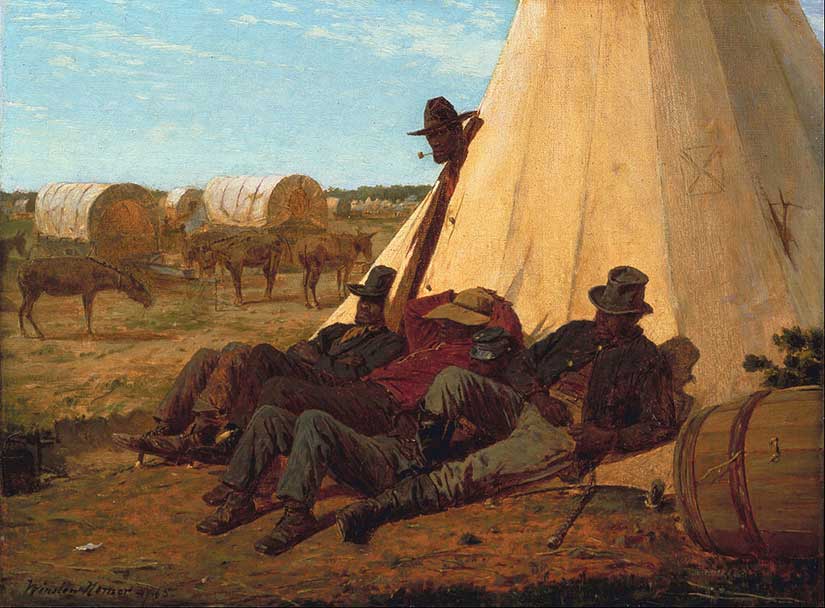

The captain of Company C doubled down. He imprisoned the town’s men in conical tents that looked like Native American teepees. These Sibley tents were supposed to sleep 16, but were jammed full with between 70-90 men each. The Filipinos had to sit on their haunches all night because there was not room to lay down. They were not fed dinner, and in the morning they were forced to cut down the food their families depended on. This went on for several days.

The Americans did not see the town turning against them. They only saw their own frustration: they felt alone, vulnerable, a day’s travel away from the nearest garrison. Yet they did not expect the ambush. My character Ben will narrate the whole debacle through his flashbacks. He knows it is a debacle. He has concerns about his fellow soldiers and harbors resentment against his officers, partly because he did not want to be in Balangiga or the Philippines to begin with. (He joined the army to fight for “Cuba Libre!” He had believed the propaganda—that he would be helping people against Spanish oppression—but instead found himself in Spanish shoes. He will not like the fit.)

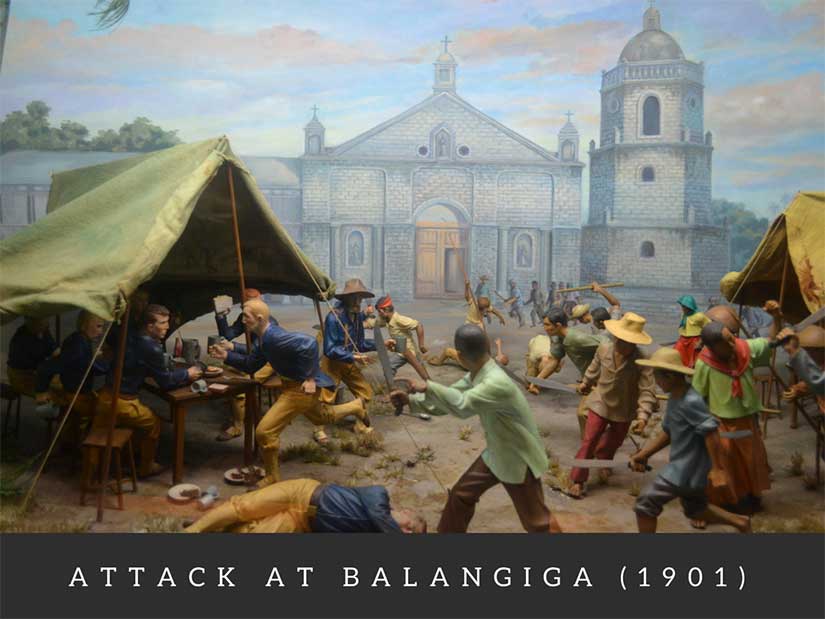

On Sunday, September 28, 1901, the morning after the town fiesta, the police chief attacked the American sentry. A church bell rang. Warriors rushed out of the jungle line east of town. Others dressed as women streamed out of the church with machetes. The American soldiers were eating breakfast. Dozens would die immediately and gruesomely. A little more than half would manage to escape, and several of them would die along the way of their wounds or from other attacks. In total, 48 of 77 Americans would die.

Americans blamed the Filipino revolutionaries—General Lukban’s men in the interior of Samar—but the truth Borrinaga and Couttie uncovered is that the town actually planned the attack themselves. They may have borrowed some men from villages outside Balangiga proper, and they may have coordinated with the revolutionaries, but this was a town fighting back against the soldiers who had imprisoned them.

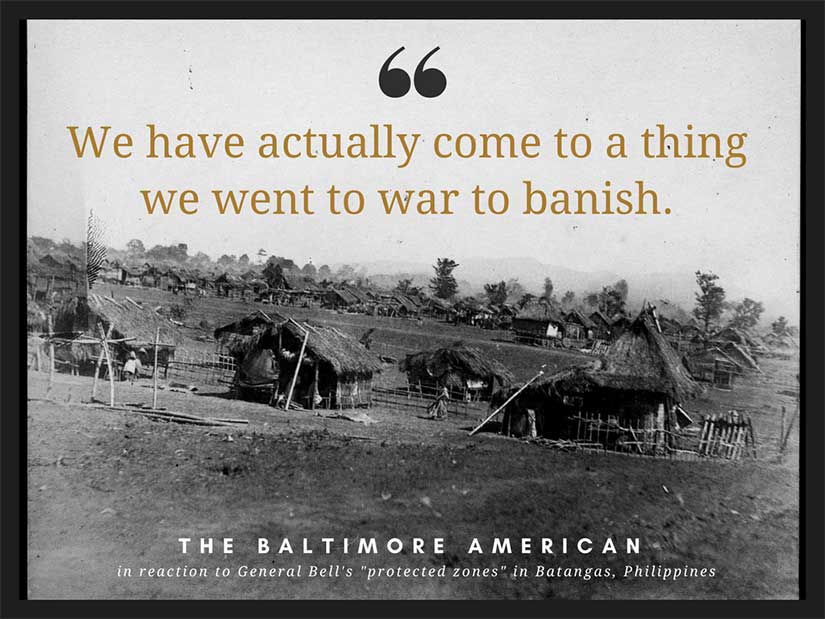

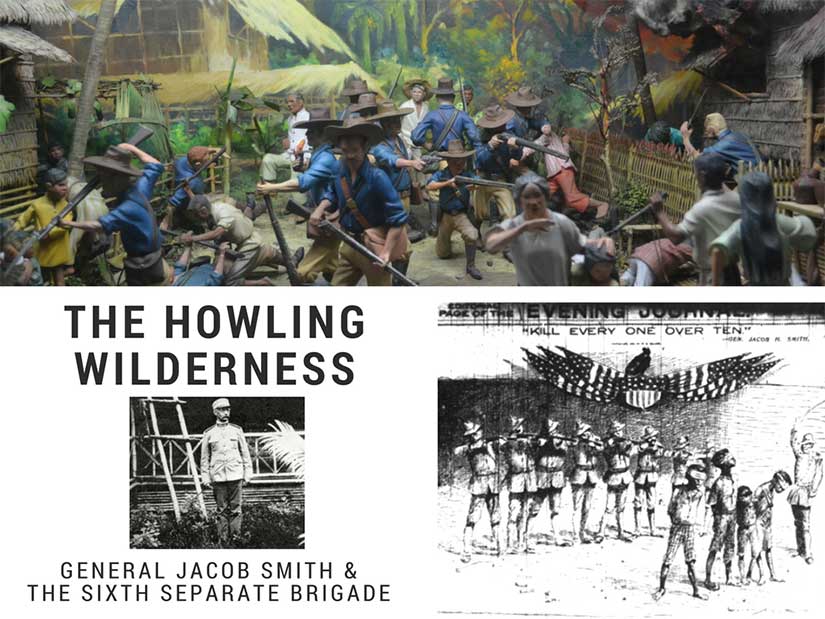

After that, all hell broke loose. If there is something more violent than the rising up of an occupied people, it is the revenge exacted by a conventional military force armed to the teeth. The American commander in Samar ordered his men to turn the entire island into “a howling wilderness” by striking down all men and boys capable of carrying arms, which he defined as all those over ten years old. His orders were in direct violation of General Order No. 100, which served as the American law of war at this time.

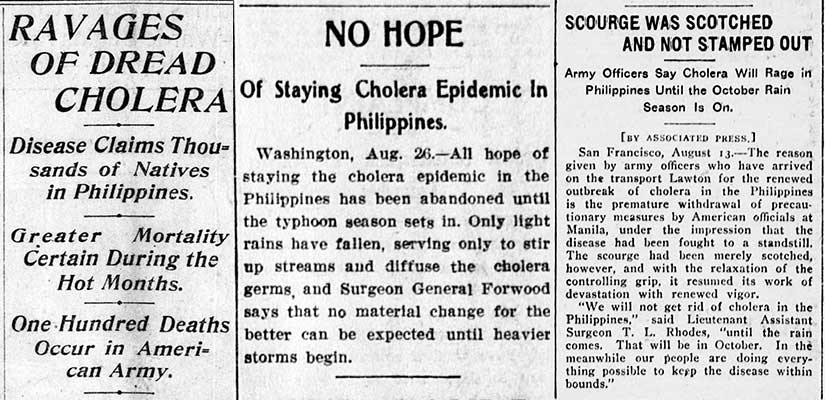

American soldiers made a special trip back to Balangiga to burn down the town and kill anyone in sight. Months of revenge resulted in the deaths of thousands on Samar, maybe as many as 15,000, according to Borrinaga. The destruction was so widespread that it sowed the seeds for a whole new war only three years later.

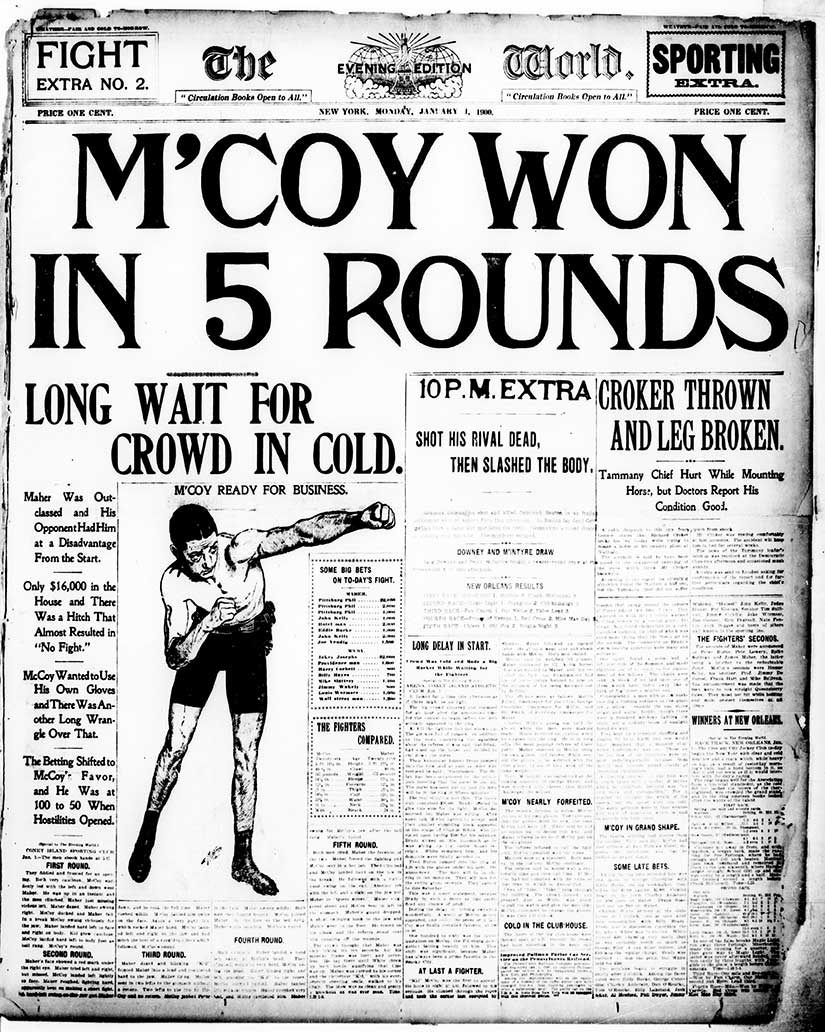

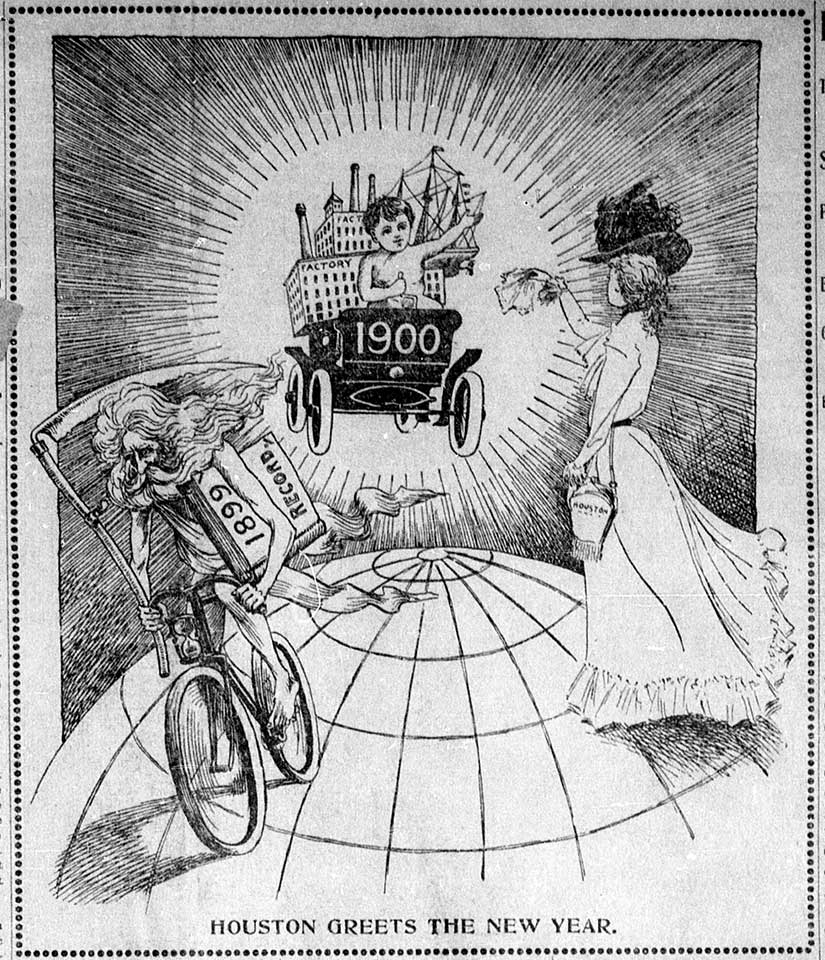

This was the My Lai moment of the Philippine-American War, and it was just as explosive to the American public as that incident in Vietnam was. For the first time, with the advent of the trans-Pacific telegraph cable, the American public could follow events with an immediacy that had been previously impossible. The excesses of the Army now blanketed newspapers and magazines Stateside. Though military authorities tried to censor the press by controlling the telegraph lines out of Manila, reporters got around this by traveling to Hong Kong to wire their stories. The courts-martial of several American officers made daily headlines, and Senate hearings began on the issue of American atrocities in the Philippines.

But how do you criticize the methods of occupation without questioning the whole endeavor to begin with? You can blame a few “bad apples” to satisfy the public, but is it enough? The general in Samar received a slap on the wrist from the court-martial that followed, and though popular outcry in the US later forced President Roosevelt to demand the general’s retirement, the punishment still didn’t fit the crime. The general retired with a full pension. Similarly, the American lieutenant in command at My Lai, convicted of murdering 22 Vietnamese civilians, served only three years, much of it under house arrest. In both cases, “marked severities” divided the American public.

George Santayana wrote in 1905: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” It is fitting he said so at the outset of what was later called the American Century. The vigorous debate about the use of military force abroad—and it’s aftereffects like PTSD—are familiar to people today. But they were not really a part of American discourse until the Philippine-American War.

Maybe it is not good enough to just remember the past. We need to keep talking about it.