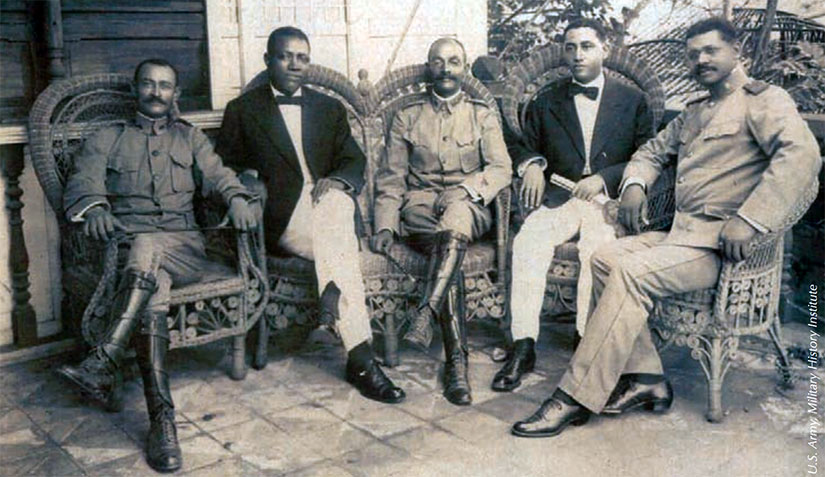

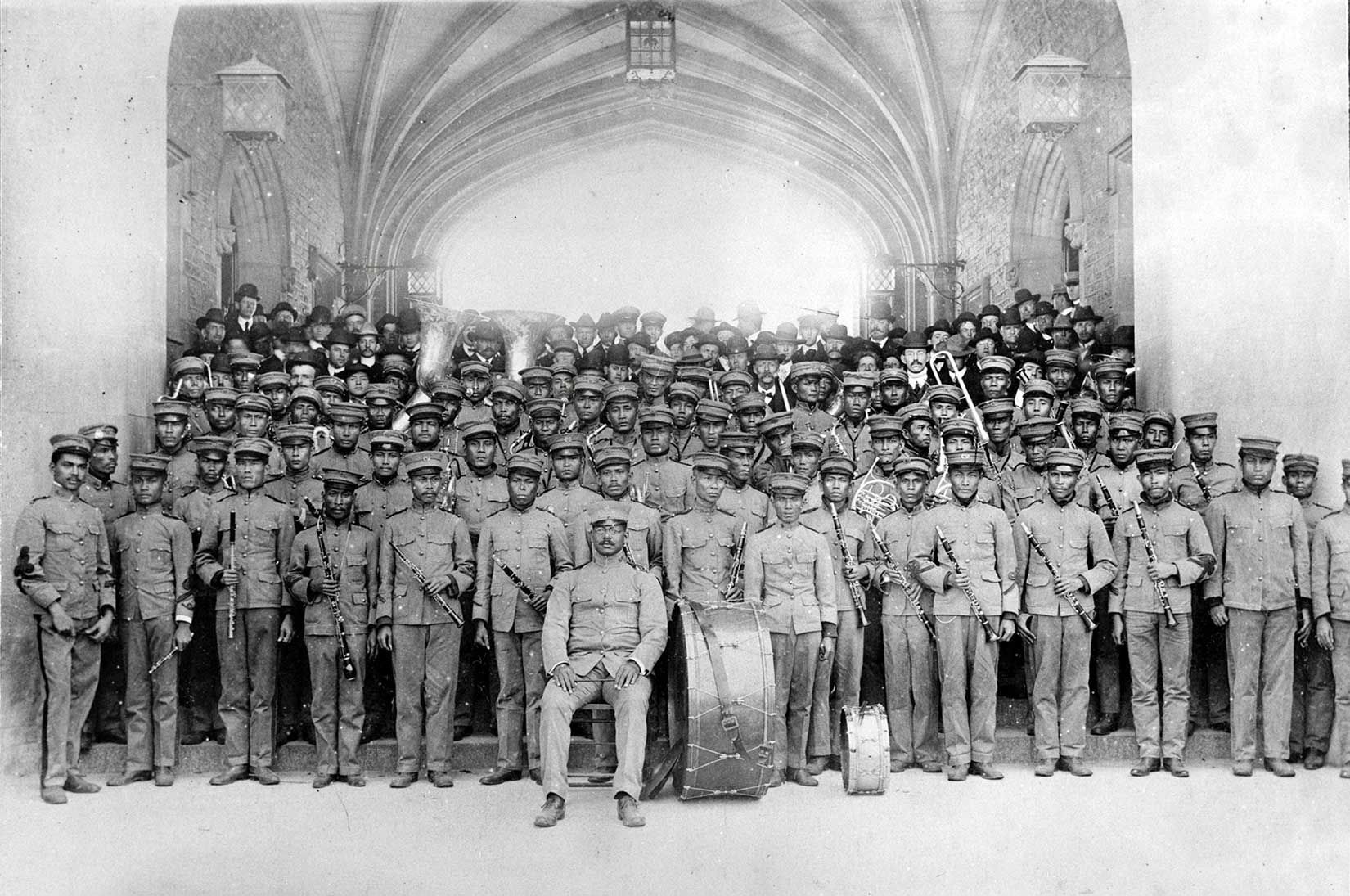

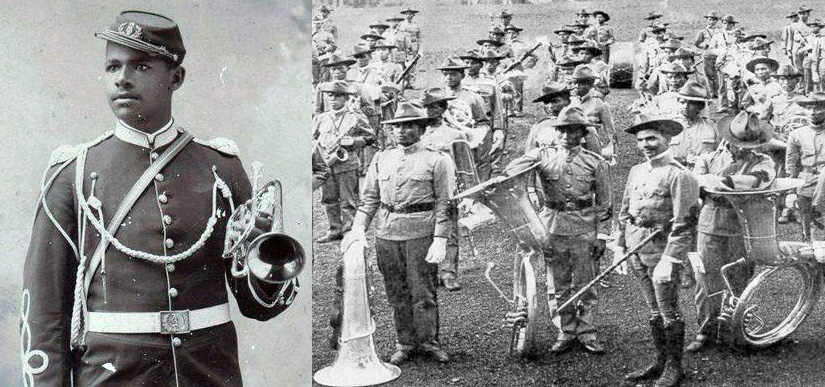

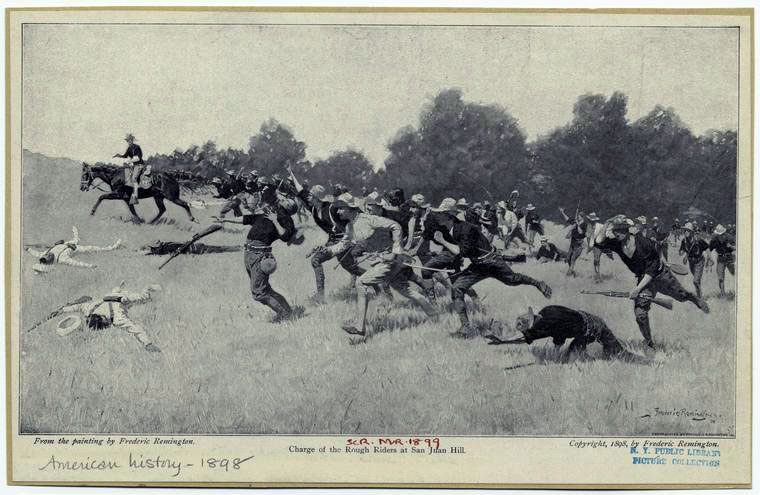

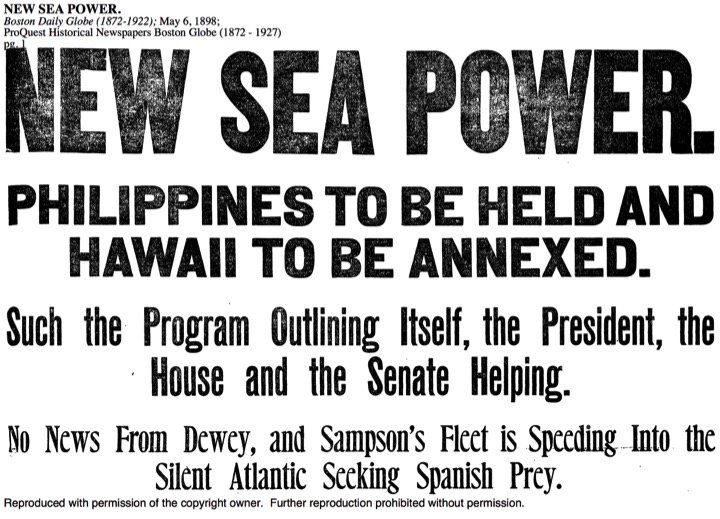

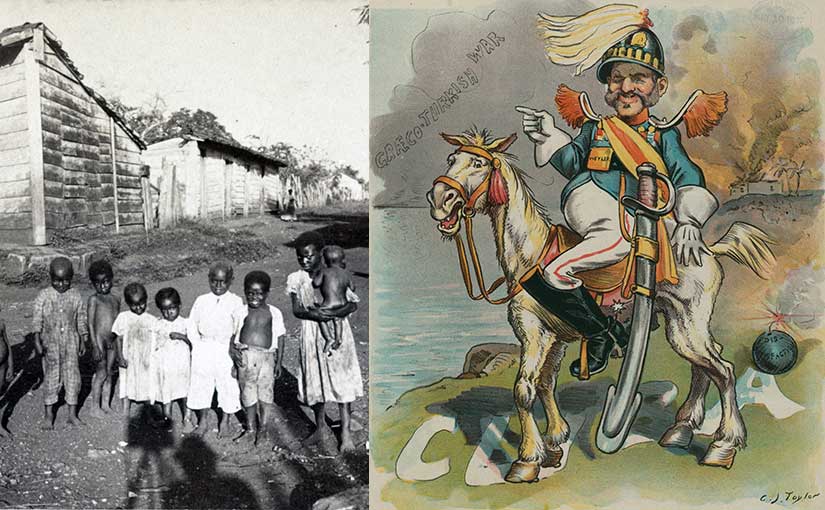

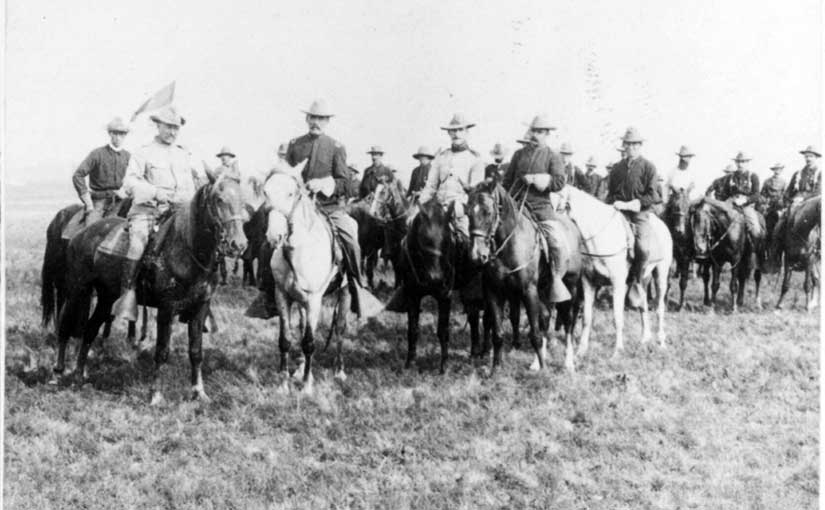

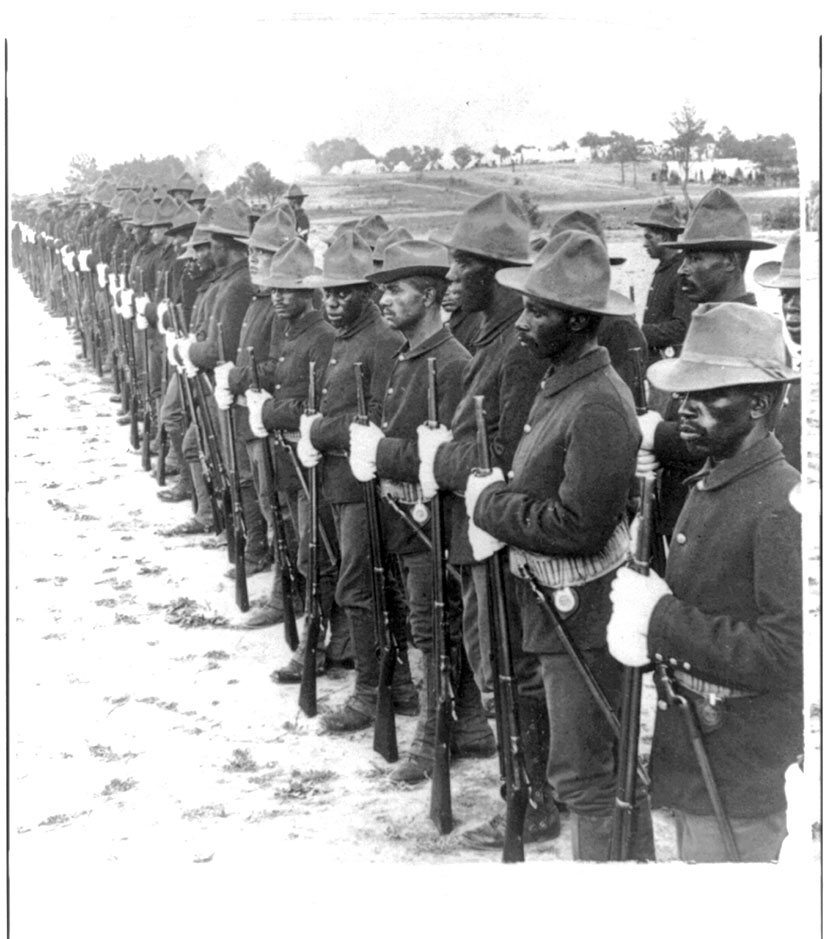

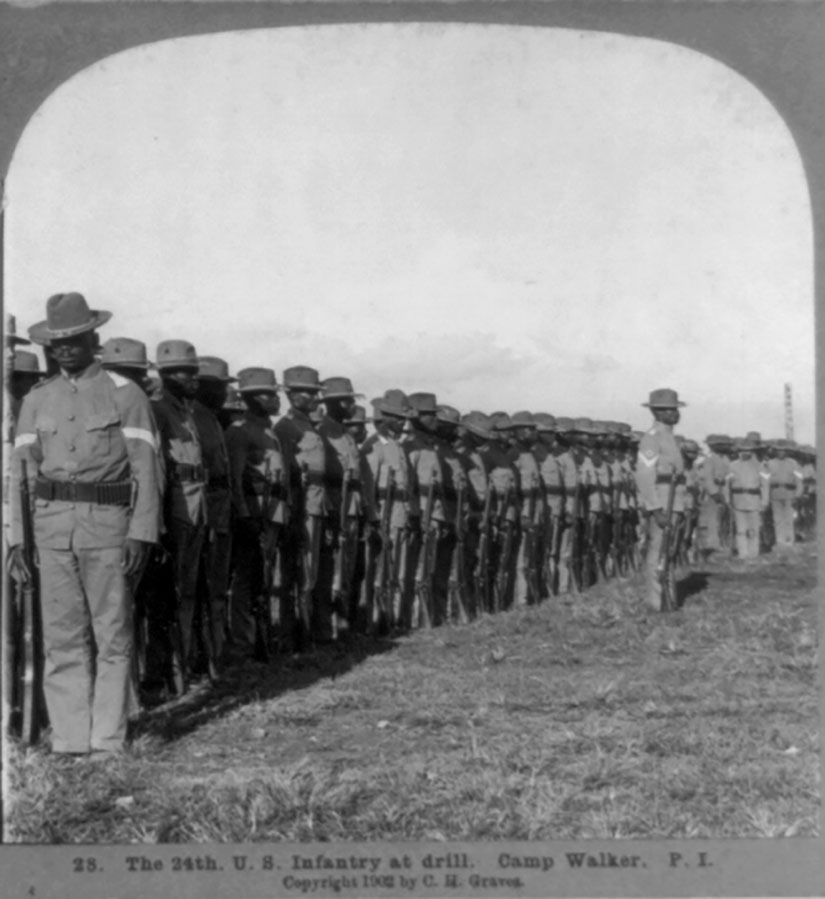

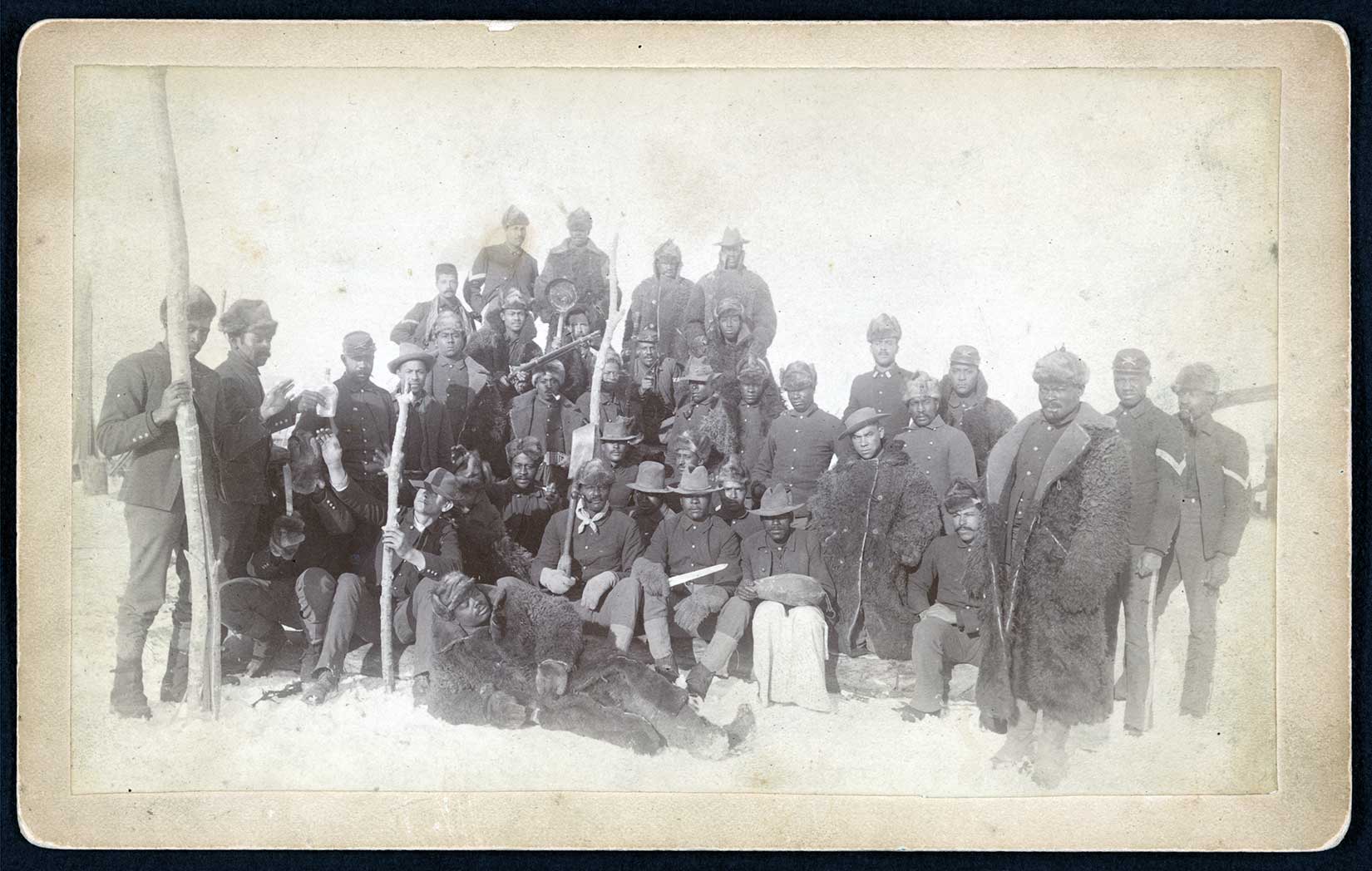

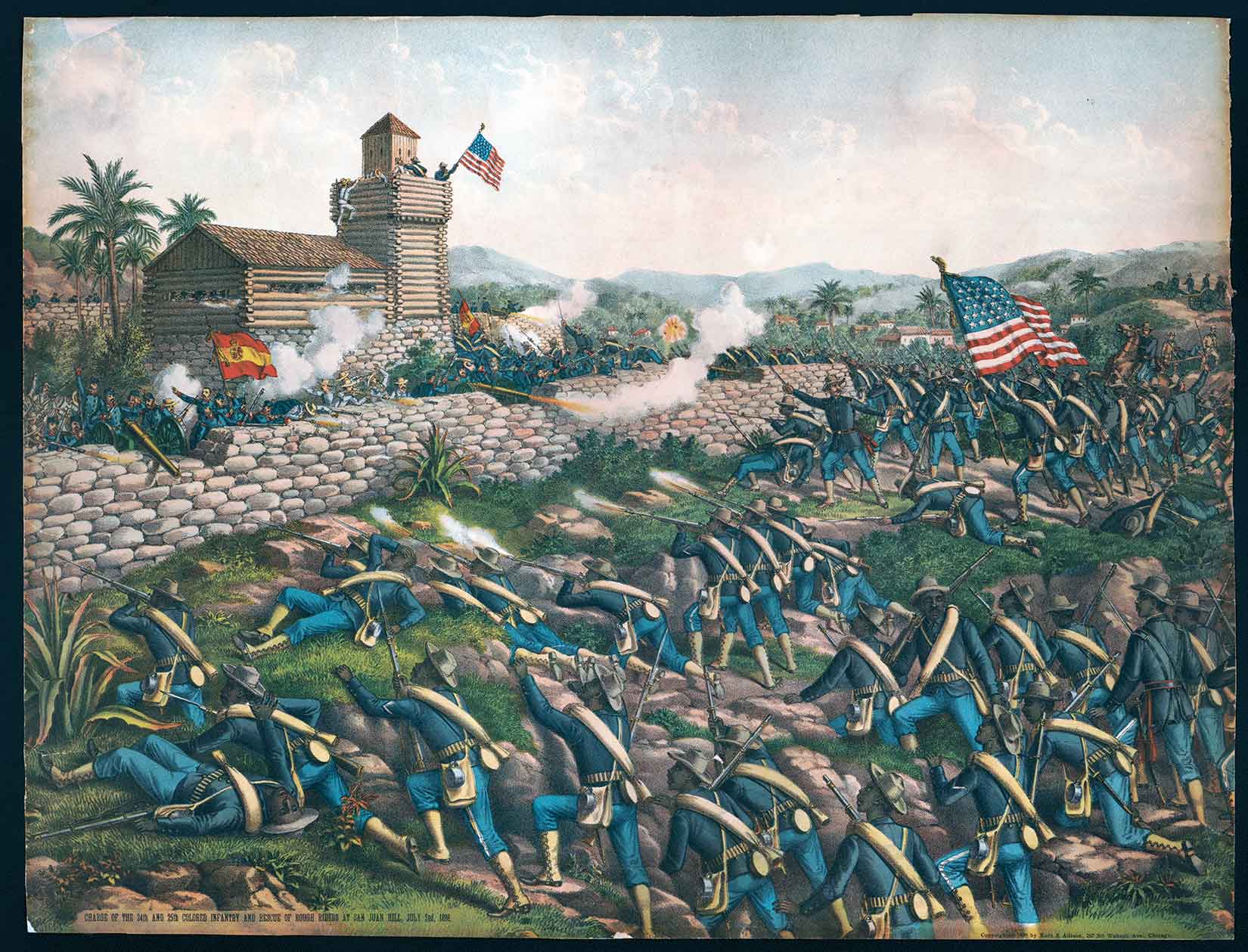

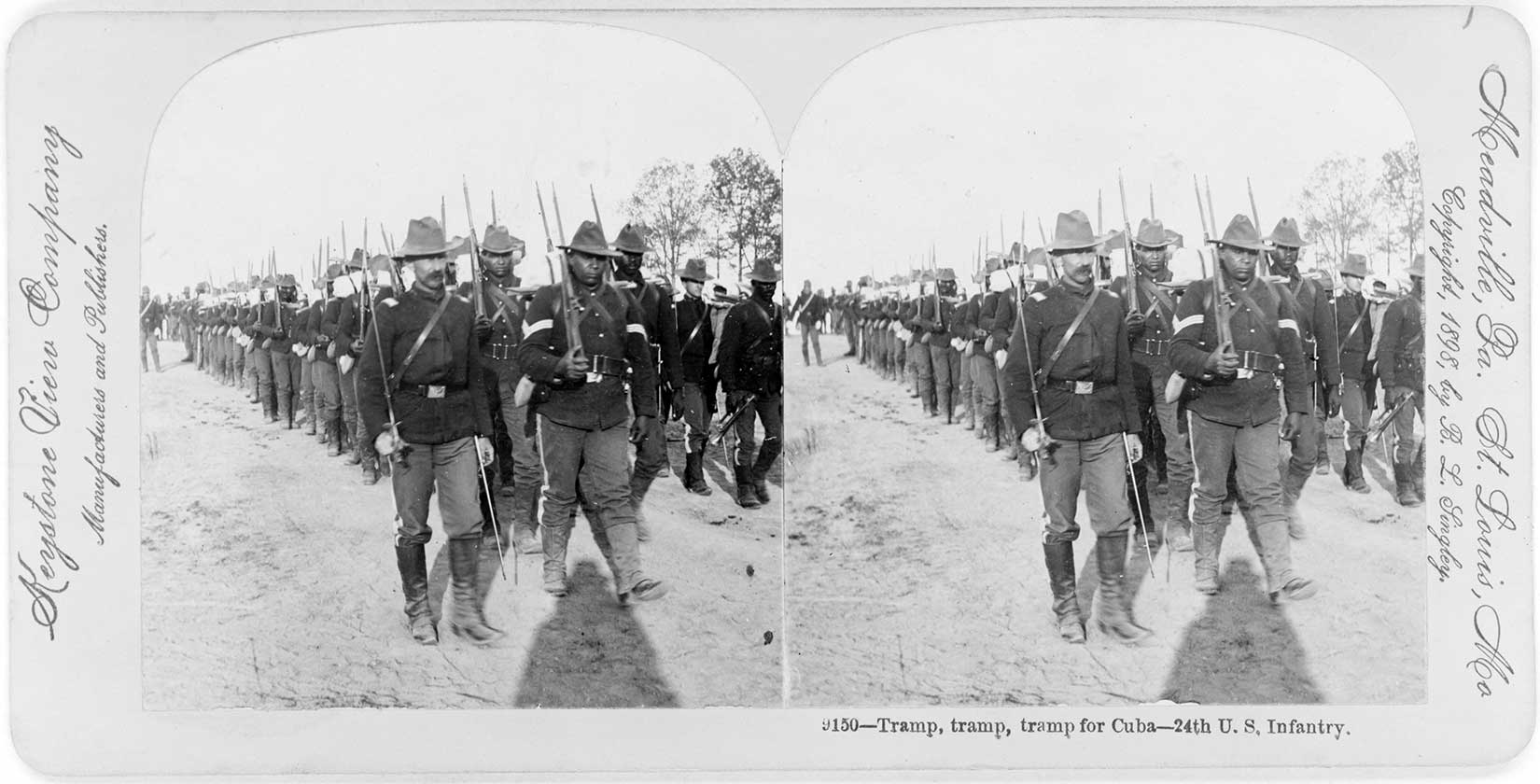

In November of 1899 the Philippine-American War shifted into a long stage of protracted guerrilla warfare. Outnumbered by the uniformed Filipino revolutionaries by more than three to one, and with white volunteer regiments rotating home at the end of their year-long enlistments, the War Department transferred 6000 African American soldiers to the Philippines (Russell 2014, 205). This included the 24th and 25th Infantries to the Philippines, as well as two newly-formed regiments (the 48th and 49th US Volunteer Infantries), and both the 9th and 10th Cavalries (New York State Division).

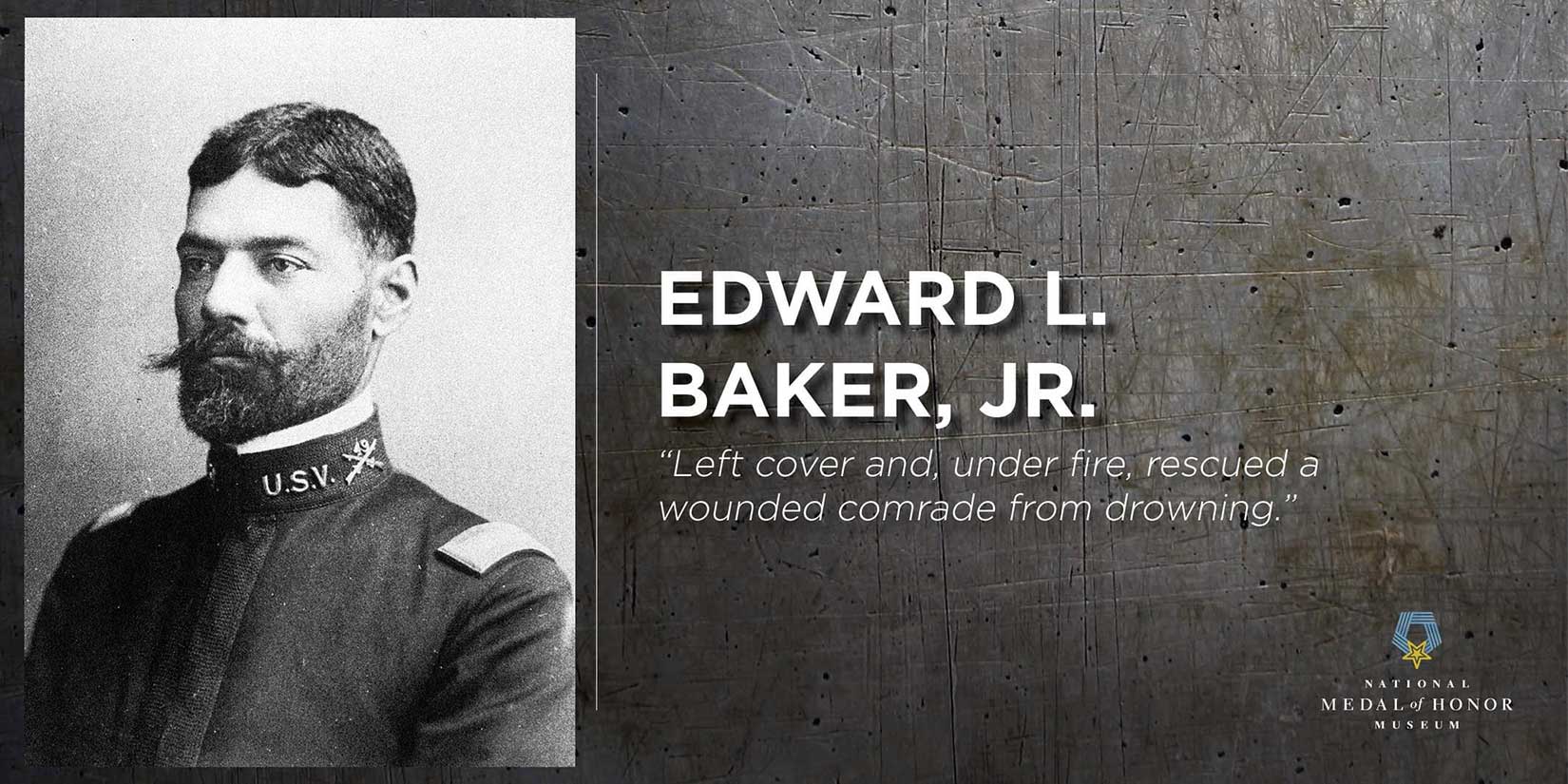

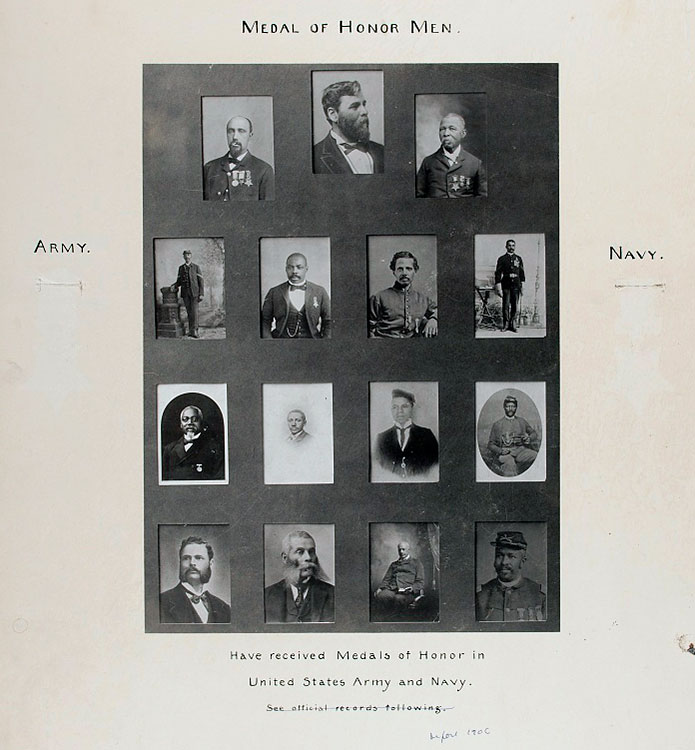

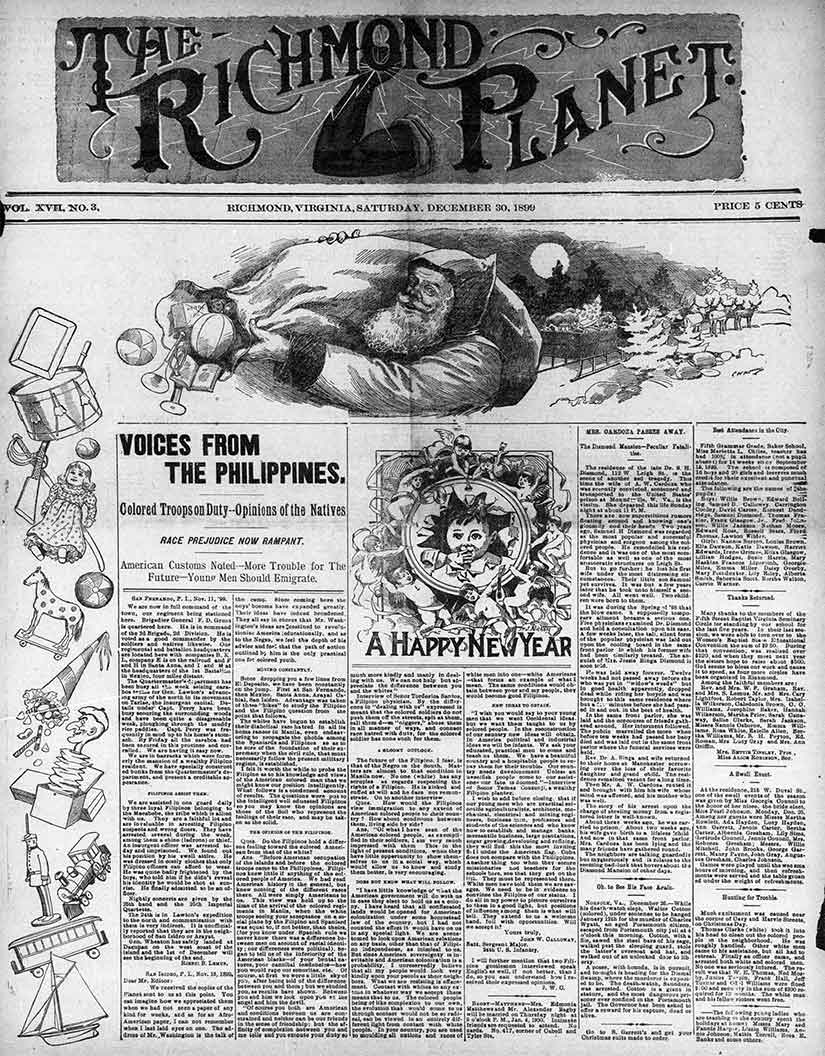

There was good reason to call upon them: many of these men had achieved the highest military honors in the land due to their courage and valor under fire. The new arrivals “built and maintained telegraph lines, constantly performed patrol and scouting duties, provided protection for work crews constructing roads, escorted supply trains, and located and destroyed insurgent ordnance and other supplies” (Russell 2014, 205-6). But there would be a cost for doing their jobs too well. Sergeant Major John W. Calloway, experienced soldier and reporter for the Richmond Planet, called out the incongruency between empire and democracy—in private correspondence—and he was punished for it.

relations with the Filipino public

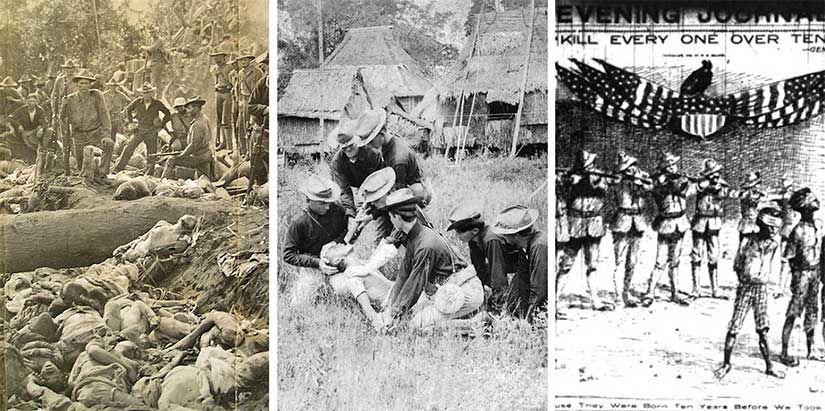

In November 1899, while the 25th Infantry was operating in the north of the country, they planned the raid of an enemy stronghold. In a war where “marked severities” were common enough among white units to warrant a later Senate investigation, the 25th kept their discipline. “In an instance of impressive restraint, these African American soldiers refused to massacre the unprepared and unorganized Filipino troops; instead they took over a hundred prisoners and captured stores of food, ammunition, and weapons” (Russell 2014, 205-6).

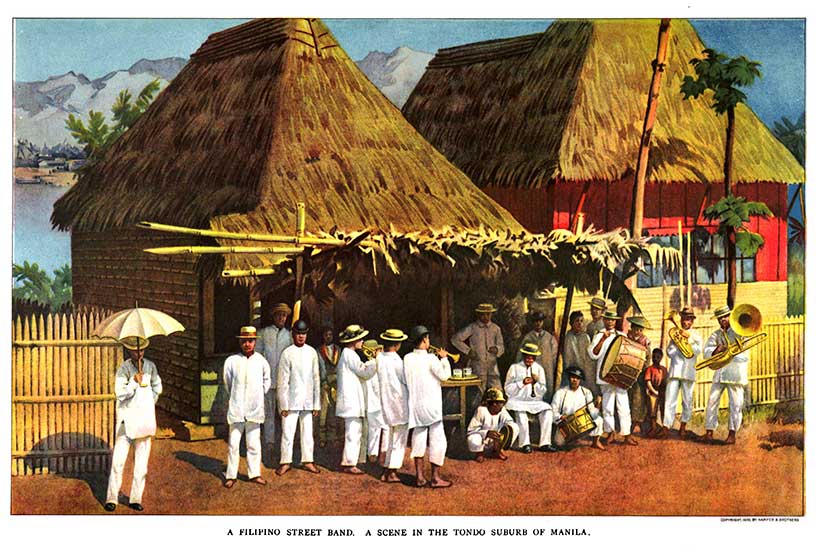

Filipino citizens immediately noticed the difference. As Filipino physician Torderica Santos told Sgt. Maj. Calloway:

Of course, at first we were a little shy of you [Black soldiers], after being told [by the whites] of the difference between you and them; but we studied you, as results were shown. Between you and him, we look upon you as the angel and him the devil. Of course you both are American, and conditions between us are constrained, and neither can be our friends in the sense of friendship; but the affinity of complexion between you and me tells, and you execute your duty so much more kindly and manly in dealing with us. We can not help but appreciate the difference between you and the whites (“Voices from the Philippines” 1899, 1).

In the article in the Planet, Calloway explains what passes as treating Filipinos kindly, at least by American Army standards: not spitting at them in the streets or calling them racial epithets (“Voices from the Philippines” 1899, 1).

Because of this relatively sympathetic treatment, some Filipinos were eager to have all American officials in their country be African Americans. “I wish you would say to your young men that we want Occidental ideas, but we want them taught to us by colored people. . . . We ask your educated, practical men to come and teach us them,” said wealthy planter Tomas Consunji, from San Fernando, Pampanga, north of Manila (“Voices from the Philippines,” 1).

Calloway agreed. He finished the article thus:

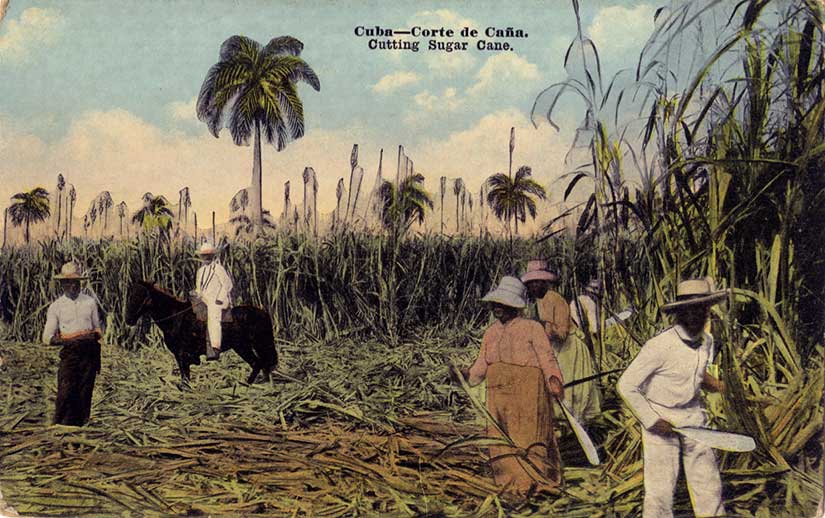

I wish to add before closing, that if our young men who are practical scientific agriculturalists, architects, mechanical, electrical and mining engineers, business men, professors and students of the sciences and who know how to establish and manage banks, mercantile business, large plantations, sugar growing, developing and refining, they will find this the most inviting field under the American flag. Cuba does not compare with the Philippines. Another thing too when they secure missionaries and teachers for the schools here, see that they get on the list. They must be represented there. . . . They extend to us a welcome hand, full with opportunities. Will we accept it? (“Voices from the Philippines,” 1).

Notice that in Calloway’s printed work, he agreed with the Progressives in their nation-building programs of “benevolent assimilation.” At least, he supported programs that provided opportunities for carpetbaggers of every race. A letter by Captain F. H. Crumbley of the 48th Volunteers printed in the Savannah Tribune agreed: “There are every openings here for the Negro in business, and room for thousands of them” (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 49).

Many Black soldiers did stay behind in the Philippines, according to another letter by Sergeant Major T. Clay Smith of the 24th Infantry in the Savannah Tribune: “ . . . several of our young men are now in business in the Philippines and are doing nicely, indeed, along such lines as express men, hotels and restaurants, numerous clerks in the civil government as well as in the division quartermaster’s office, and there are several school teachers, one lawyer, and one doctor of medicine” (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 49). Others became agricultural tycoons, judges, or small business owners (Ontal 2002, 129).

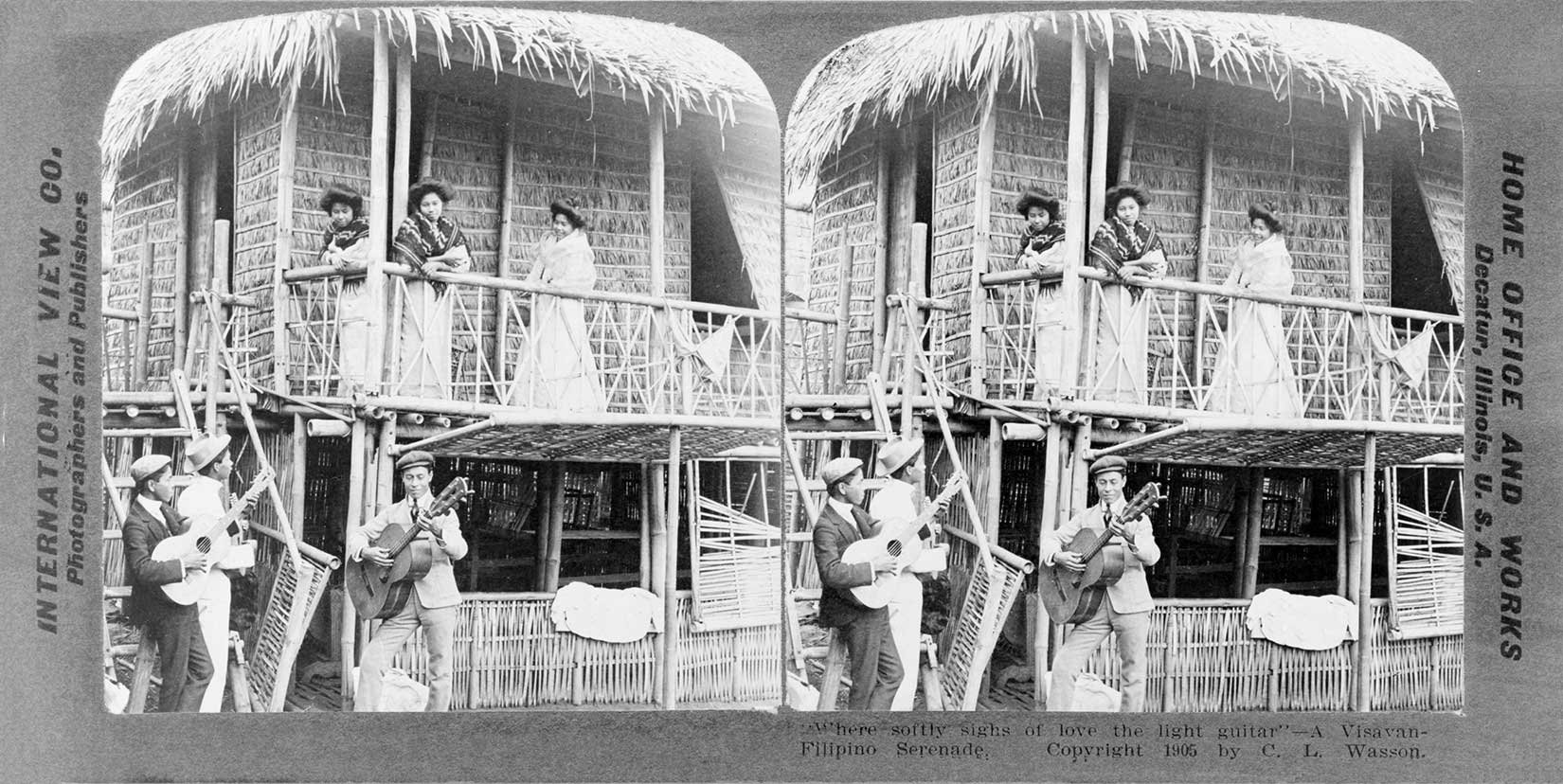

There was room for romance too. “Arguably, the Philippine islands had in its possession history’s largest proportion of African-American soldiers who opted not to return home after completing military service abroad” (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 51). Over a thousand of the soldiers deployed in the Philippines married Filipino women and stayed in the islands (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 50). In fact, Governor Taft admitted that he feared that these soldiers got along “too well with the native women,” and so he sent the rest of the Black regiments Stateside as quickly as possible (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 50).

too much democracy? Or not enough.

Got along too well? Exactly. In 1907 Stephen Bonsal, a Black correspondent in the Philippines wrote: “While white soldiers, unfortunately, got on badly with the natives, the black soldiers got on much too well. . . . the Negro soldiers were in closer sympathy with the aims of the native populations than they were with those of their white leaders and the policy of the United States” (quoted in Russell 2014, 213).

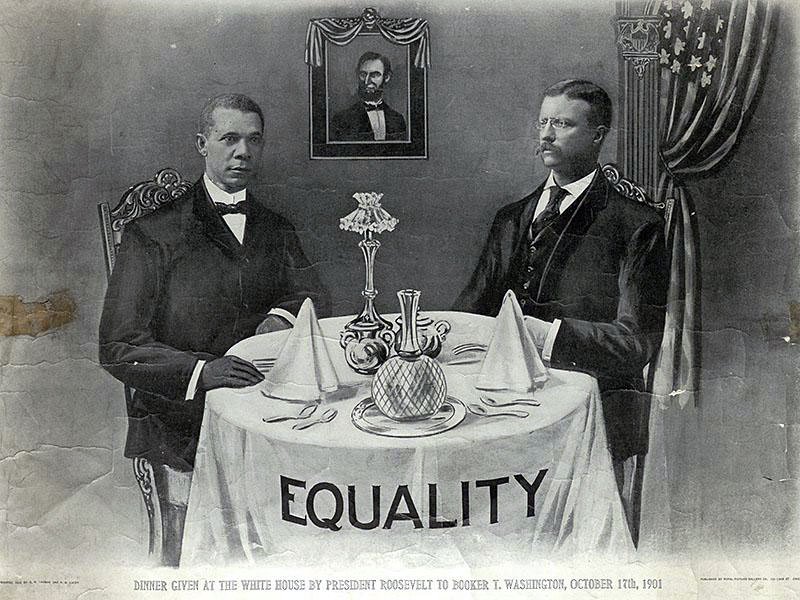

For example, Robert L. Campbell wrote to Booker T. Washington: “I believe these people are right and we are wrong and terribly wrong. I am in a position to keep from bearing arms against them and I will try and keep myself in such position until we are mustered out; of course, if I am ordered to fight, I will obey orders as a soldier should . . .” (quoted in Russell 2014, 212). But what if others did not obey orders?

That was the worry when Sergeant Major Calloway’s case came to light. He had revealed a “dangerous” level of humanitarianism in private correspondence to his friend Tomas Consunji (Boehringer 2009, 3):

After my last conference with you and your father, I am constantly haunted by the feeling of what wrong morally we Americans are in the present affair with you. . . . Would to God it lay in my power to rectify the committed error and compensate the Filipino people for the wrong done! . . . The day will come when you [Filipinos] will be accorded your rights. The moral sensibilities of all America are not yet dead; there still smolders in the bosom of the country a spark of righteousness that will yet kindle into a flame that will awaken the country to its senses, and then! (Quoted in Russell 2014, 209).

In 1901, when white soldiers of the 3rd Infantry searched Consunji’s home for evidence of ties to nationalists, they found the correspondence between the two men. They sent it on to Calloway’s commanding officer, Colonel Henry B. Freeman of the 24th, a white man who had only been in the country for three months (Boehringer 2009, 2). Though Calloway claimed that the letters only expressed “a personal feeling, expressed to a personal friend, [and] had no other intent or motive,” the colonel believed them treasonous.

Colonel Freeman wrote in the official report: “Battalion Sergeant Major Calloway is one of those half-baked mulattoes whose education has fostered his self-conceit to an abnormal degree” (quoted in Russell 2014, 213). If Calloway had an abundance of confidence, he had earned it through active service since 1892. He had done strike- and riot-breaking in the western mining states, along with hostage rescue, before fighting in three separate expeditions of the Cuban and Philippine fronts (Russell 2014, 215) and achieving the highest enlisted rank possible (Scot 1995, 166). Now, he wished to stay and invest his $1500 savings in a business venture in Manila, but he was thrown in Bilibid Prison instead. All this because of private correspondence, obtained by a possibly illegal search, that effectively said that imperialism was immoral—the very principle on which the United States of America was supposedly founded (Russell 2014, 212-13).

In this and future American wars, one of the key tenets of counterinsurgency has been that military action alone will not encourage forces of resistance to set down their arms. People must see the carrot, not just feel the stick. In the Philippine-American War, the military leaders called this strategy “attraction.” Later, during another counterinsurgency in the Philippines, this time against communists during the 1950s, it was called “civic action.” In Vietnam, civilians colloquially called it “winning the hearts and minds” of the people. Good rapport, then, is an asset, not a liability. If African American regiments were forming true friendships with Filipinos, why were the white commanding officers so angry?

The Inspector-General would state: “I regard [Calloway] as a dangerous man, in view of his relations with the natives, as shown by this letter, and the circumstances of his court-martial” (Boehringer 2009, 3). Colonel Henry B. Freeman said of Sergeant Major John W. Calloway: “In my opinion he is likely to step into the Filipino ranks, should a favorable opportunity occur” (Russell 2014, 213). General Arthur MacArthur, commander of the entire war and father of future General Douglas MacArthur, agreed: “It is very apparent that [Calloway] is disloyal and should he remain in these islands, he would undoubtedly commit some act of open treason and perhaps join the insurrection out and out. One man of the 24th Infantry by the name of David Fagen has already done so and as a leader among the insurrectos is giving great trouble by directing guerrilla bands” (Boehringer 2009, 3).

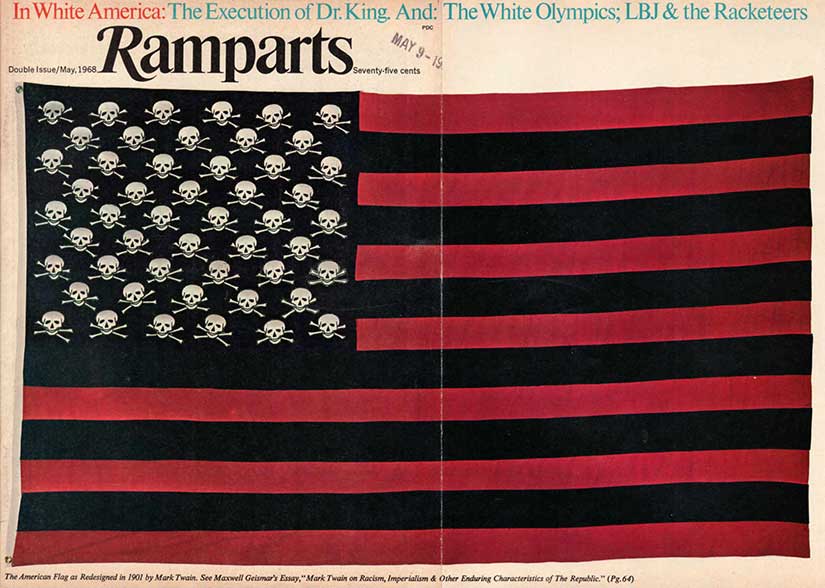

David Fagen’s story is worth a post of its own later, but this man was one of twenty-nine African American soldiers to desert the Army in the Philippines, and one of nine who defected to the Philippine Revolutionary Army (Robinson and Schubert, 73 n23). It is important to note that fourteen white soldiers also defected to the Filipino side (McCann and Lovell, 54), though that number was a smaller percentage of those who served in the islands. What particularly upset MacArthur about a Black soldiers’ defection was probably the phenomenon described by Ibram X. Kendi: “Negative behavior by any Black person became proof of what was wrong with Black people, while negative behavior by any White person only proved what was wrong with that person” (2017, 42-43).

Black soldiers were specifically targeted by Filipino propaganda leaflets that brought up the same questions their own papers were asking back home (New York State Division). One read:

To the Colored American Soldier: It is without honor that you are spilling your costly blood. Your masters have thrown you into the most iniquitous fight with double purpose—to make you the instrument of their ambition and also your hard work will soon make the extinction of your race. Your friends, the Filipinos, give you this good warning. You must consider your history, and take charge that the Blood of Sam Hose proclaims vengeance (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 46).

This letter was attributed to President Emilio Aguinaldo, but many believe it was penned by Foreign Minister Apolinario Mabini (Ontal 2002, 125), the polymath genius who had studied American history and society closely enough to reference the “spectacle lynching” and mutilation of Sam Hose of Newnan, Georgia. It was hard to ignore letters like Mabini’s. Even worse, it was hard not to notice how the new American regime was recreating the world of Sam Hose around them—and to wonder whether they, as soldiers in the US Army, were complicit in this expansion of segregation.

Racism and segregation in the military had clearly been at fault in causing Fagen’s defection. Fagen had been considered by his former white officers as “rowdy,” “bucking” his superiors, “a good for nothing whelp,” and “in continual trouble with the Commanding Officer” (Ontal 2002, 125). He had even been charged with seven counts of insubordination and punished with “all sorts of dirty jobs” (Ontal 2002, 125). After he defected, the colonial newspaper Manila Times depicted Fagen “as a gifted military tactician waylaying American patrols at will and then evading large forces sent in pursuit” (Ontal 2002, 126). He showed his former officers of the 24th Infantry exactly how wrong they were.

The fear of MacArthur and others was this: what if Calloway, the highest-ranking African American in the 24th, followed Fagen into the Philippine Revolutionary Army or any of the guerrilla organizations fighting in its name? Unlike Fagen, Calloway was already proven to be competent, highly-educated, and a fine leader. What damage could he do to the United States Army?

But this fear was all in their heads! There was no evidence that Calloway ever considered defection. He hoped for both peace and Filipino rights, but he trusted in the people of the United States to provide both. The fact that the white officers understood Mabini’s propaganda to be effective means that they recognized the truth of it—which means that they should have seen that it was American policy to blame, not the sympathies of Calloway. Nevertheless, the Army busted Calloway down to private and dishonorably discharged him. He would try to reenlist several more times, the last during World War I, but he would be denied every time (Boehringer 2009, 3).

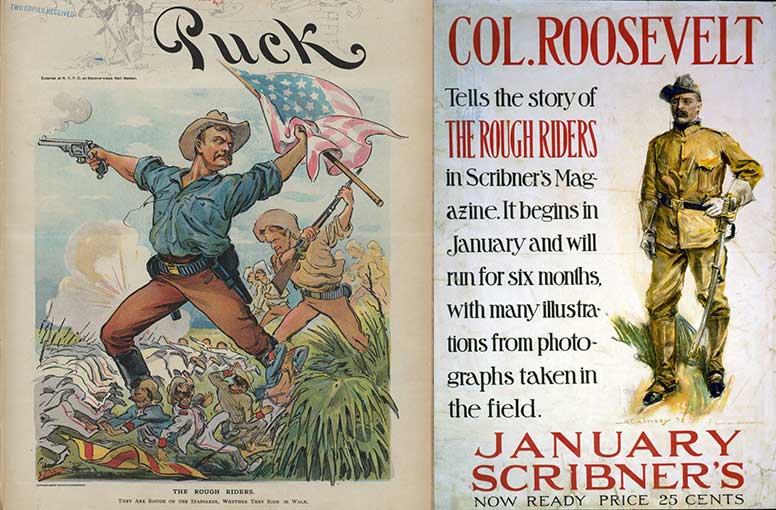

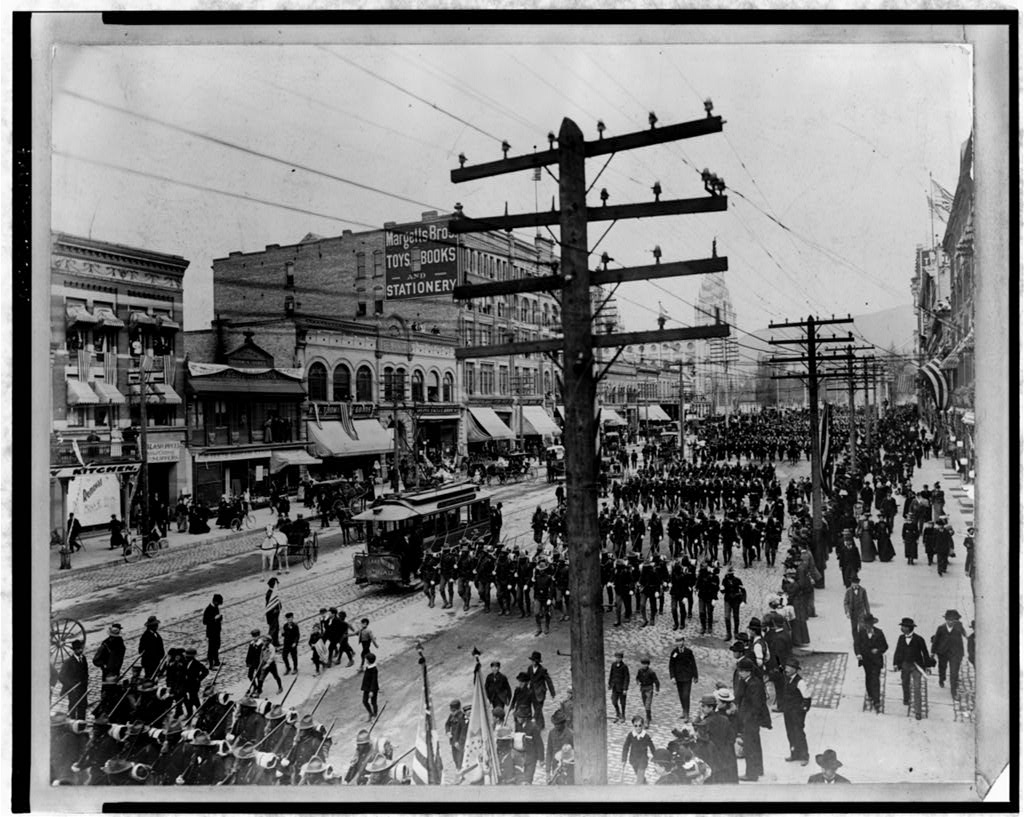

He was not the only one to be disappointed. What progress had been sought by the “Black Phalanx” was lost in the extension of Jim Crow policies throughout the empire (quoted in Gleijeses 1996, 188). The US military would not be desegregated until the Truman administration after World War II, when America’s role as the champion of democracy would be questioned by foreign allies (Kendi 2017, 351). The professionalism, excellence, and courage of African American soldiers in the 1898 wars has been largely forgotten in white-dominated histories of the period.

selected Bibliography:

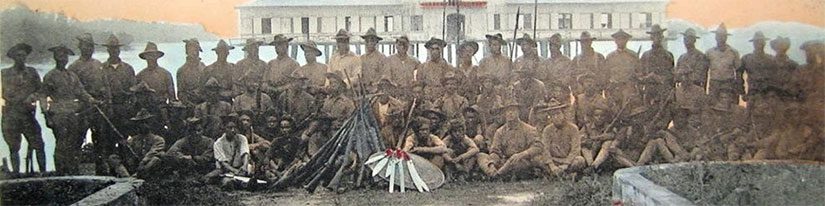

[Featured image is a vintage postcard of the 25th Infantry at Basilan in the Sulu Archipelago.]

Boehringer, Gill H. “Imperialist (In)Justice: The Case of Sergeant Calloway.” Bulalat: Journalism for the People (Manila, Philippines), April 4, 2009. Accessed August 3, 2020. http://www.bulatlat.com/2009/04/04/imperialist-injustice-the-case-of-sergeant-calloway.

Brown, Scot. “White Backlash and the Aftermath of Fagen’s Rebellion: The Fates of Three African-American Soldiers in the Philippines, 1901-1902.” Contributions in Black Studies 13, no 5 (1995): 165-173. http://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol13/iss1/5.

Gleijeses, Piero. “African Americans and the War against Spain.” The North Carolina Historical Review 73, no. 2 (1996): 184-214. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23521538.

Kendi, Ibram X. Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. New York: Bold Type Books, 2017. Kindle edition.

New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs. “Black Americans in the US Military from the American Revolution to the Korean War: The Spanish American War and the Philippine Insurgency.” New York State Military History Museum and Veterans Research Center. Last modified March 30, 2006. Accessed June 29, 2020. http://dmna.ny.gov/historic/articles/blacksMilitary/BlacksMilitaryContents.htm.

Ngozi-Brown, Scot. “African-American Soldiers and Filipinos: Racial Imperialism, Jim Crow and Social Relations.” The Journal of Negro History 82, no. 1 (1997): 42-53. http://doi.org/10.2307/2717495.

Ontal, Rene G. “Fagen and Other Ghosts: African-Americans and the Philippine-American War.” In Vestiges of War: The Philippine-American War and the Aftermath of an Imperial Dream, 1899-1999, edited by Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis Francia, 118-30. New York: New York University Press, 2002.

Robinson, Michael C., and Frank N. Schubert. “David Fagen: An Afro-American Rebel in the Philippines, 1899-1901.” Pacific Historical Review 44, no. 1 (1975): 68-83. http://doi.org/10.2307/3637898.

Russell, Timothy D. “‘I Feel Sorry for These People’: African-American Soldiers in the Philippine-American War, 1899-1902.” The Journal of African American History 99, no. 3 (2014): 197-222. http://doi.org/10.5323/jafriamerhist.99.3.0197.

“Voices from the Philippines: Colored Troops on Duty—Opinions of the Natives.” Richmond Planet. (Richmond, Va.), 30 Dec. 1899. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/1899-12-30/ed-1/seq-1/.