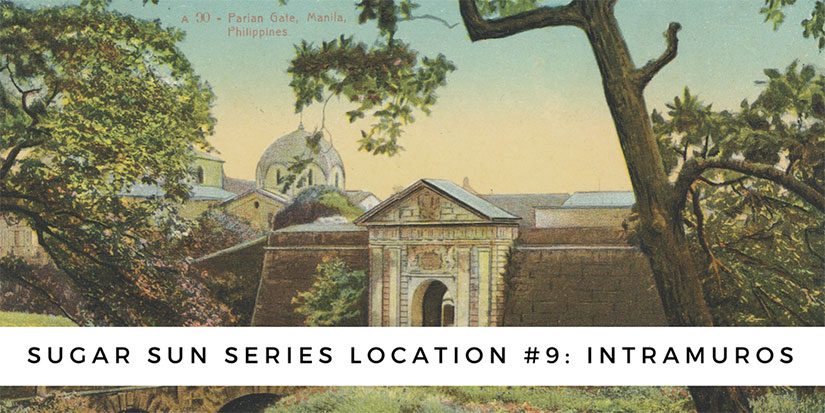

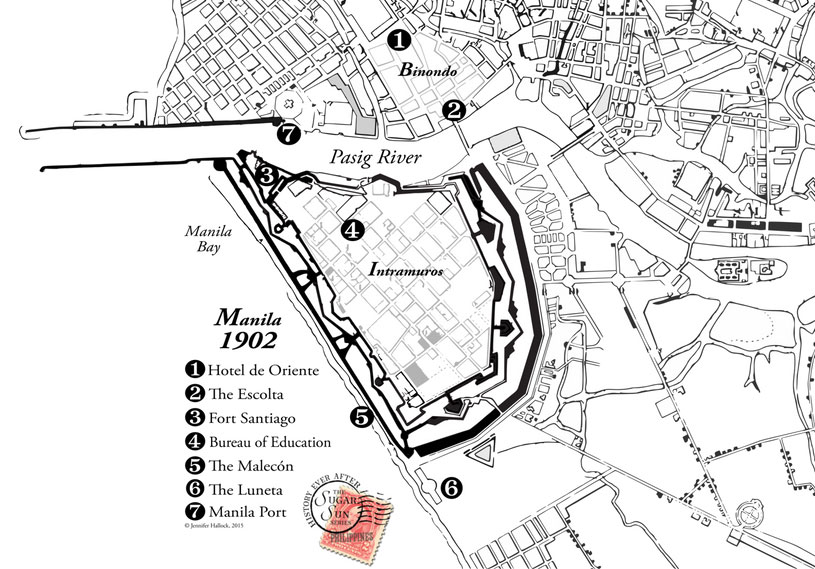

In the opening chapter of Hotel Oriente, heroine Della Berget describes Manila’s Intramuros as “an old Spanish walled enclave in the style of Gibraltar, plunked down in the middle of the tropics.”

And, in fact, that is exactly what the city’s name means: inside the walls that the Spanish built (and rebuilt and rebuilt) to protect them from those who lived outside, the Filipinos and the Chinese. Capping off the walled city was the armed citadel of Fort Santiago:

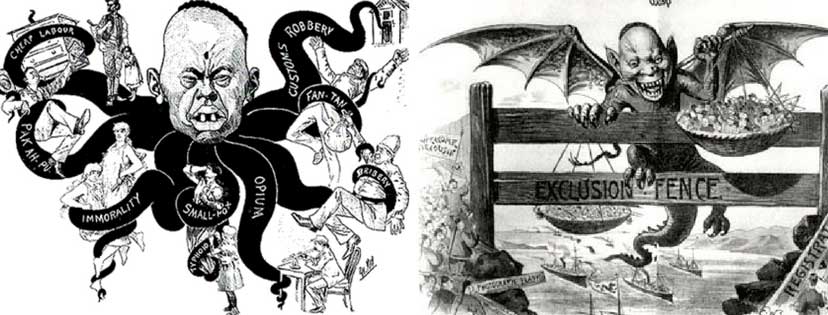

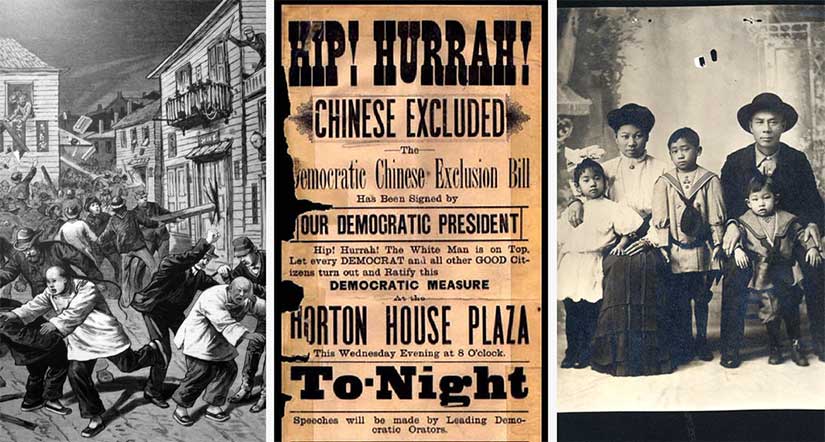

The Spanish did leave their walls on occasion. They had to if they wanted to do anything commercial. They shopped extramuros in Binondo, Manila’s Chinatown, which was within a cannon’s shot of Fort Santiago in Intramuros. The range was very intentional, by the way. The Spanish had a love-hate relationship with their Chinese immigrant neighbors, who, in many cases, had been in Manila longer than they had. Sometimes the “hate” end of things meant firing volleys. The love-hate relationship also played out in shopping, especially on a street called the Escolta. The Spanish claimed the Escolta exclusively for European merchants, but some of those merchants were supplied by Chinese in the neighboring streets. After a full day of shopping in Escolta and a lovely evening on the Luneta, the Spanish would retreat within their walls to sleep.

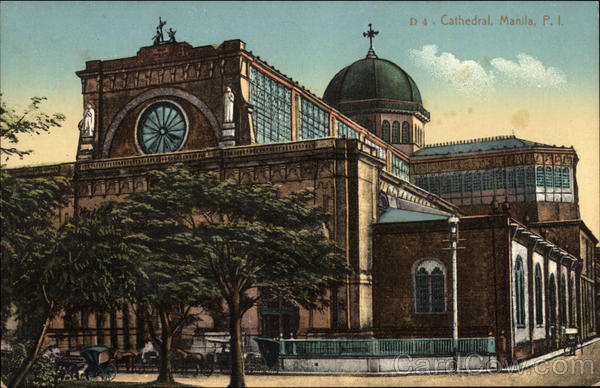

What was inside the walls? Della calls it a “Catholic wonderland”: “If she glanced up, the city was all domes, crosses, and oyster shell windows.” And no wonder: there were seven churches in Intramuros before World War II. Seven churches—grand ones, too—in a space of a mere 1/4 square mile (166 acres). It should be no surprise to you, then, if I point out that it was really the Catholic Church, via the regular orders of friars, who controlled the Philippines. This was a Crown colony in name only. The real administrators? The Dominicans, the Franciscans, the Recollects, the Augustinians, the Vincentians, the Jesuits, and more. And Intramuros was the seat of their power, where the Manila Cathedral (above) towered over the secular offices of the governor and loomed over the general’s desk in Fort Santiago.

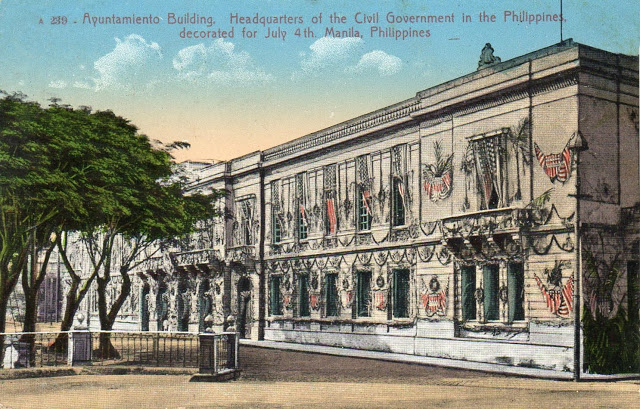

When the Americans came, they used the necessary parts of Intramuros, especially Fort Santiago and the city hall (which they confusingly mislabeled the Palace, even though the governor’s—and now president’s—residence is not inside the walls).

Actually, the Americans preferred a fresh sea breeze to the cloistered staleness of Intramuros, and they began to build up the areas south of the Luneta, including Malate and Ermita (where the US embassy compound still sits).

And, in their port expansion, they would create a whole “New Luneta” in what had previously been the Bay, and this is where they would build new social establishments, including the Manila Hotel and the Army and Navy Club. After this, many Americans had few reasons to enter Intramuros at all. Too bad.

Nor did the Americans like the medieval air (really, stench) of the moat surrounding Intramuros. In classic American form, they turned it into a golf course.

Yes, this hardly sounds very populist, but the colonial administration was not inclusive—and, to be fair, the short but challenging par-66, 18-hole course is now owned by the government and can be played by anyone for around $20 (residents) or $30 (tourists).

Intramuros suffered most at the end of World War II, when it was the site of the last stand between the occupying Japanese and liberating American forces. The Japanese unleashed a reign of terror on the occupants of Intramuros and Manila at large, known as the Rape of Manila. The Americans, seeking to force a surrender, bombed the city into oblivion, destroying 6 of the 7 churches in Intramuros. In fact, Intramuros was such a disaster that it was ignored during the post-war rebuilding phase and has only recently started to see a renaissance of cultural, social, and commercial activities. If you are in Manila, take a tour with performance artist Carlos Celdran, and he will make you see Intramuros in a whole new light.