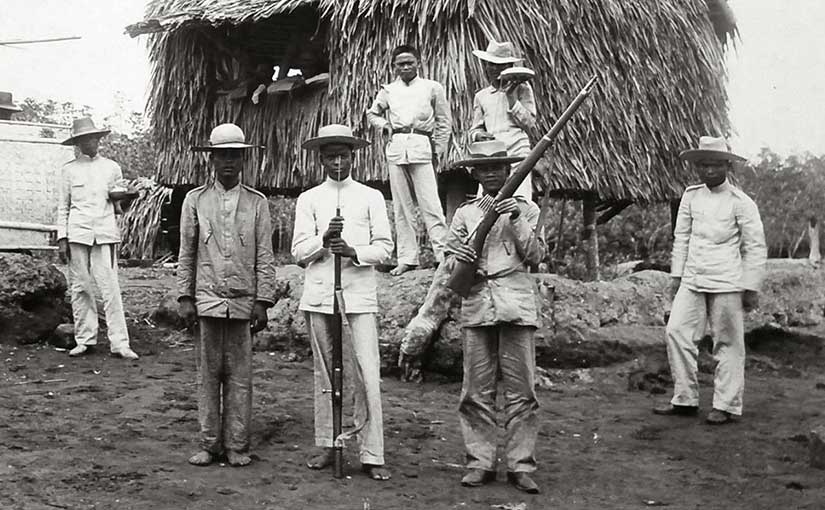

Though the conflict began over events in Cuba, America fought its first battle of the Spanish-American War in Manila. Historians debate what President McKinley’s intentions were—did he want to take the Philippines in its entirety, just keep Manila, or defeat Spain and leave? But, as they say, “appetite comes with eating.” Once the Americans had Manila, they wanted all the islands. Only problem? The Philippine revolutionaries who helped defeat the Spanish did not want the Americans to stay—and they controlled most of the rest of the country.

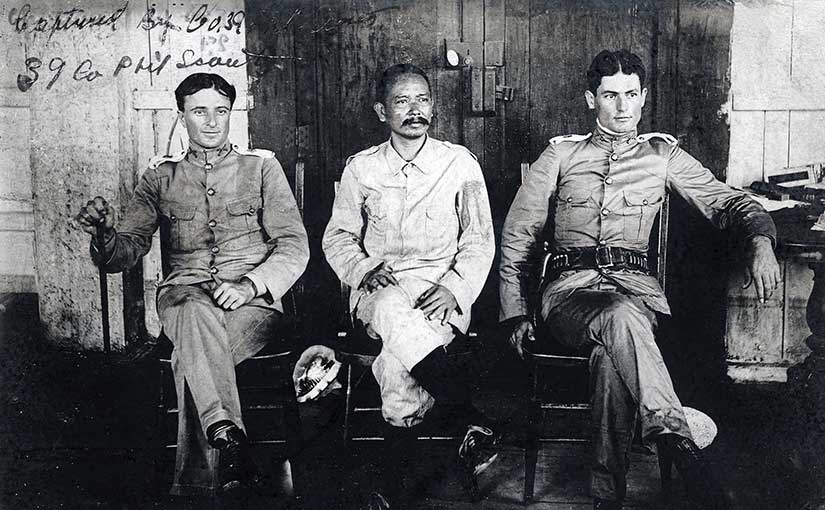

Instead of calling what followed a war—assuming two equal adversaries—the Americans called it the Philippine Insurrection—with only one legitimate authority. (The Spanish sold the islands to the Americans for $20 million in December 1898, which was the basis of their legal claim. On what authority the Spanish sold the Philippines, that is another question.) So instead of calling the Filipinos revolutionaries, patriots, or nationalists, they called them insurgents, bandits, and ladrones. (The last two are the same thing, the latter in Spanish.) The favorite American term, though, was insurrecto (insurrectionist).

Now the conflict is called the Philippine-American War, and it officially lasted from 1899 to 1902, though hostilities did not fully end until 1913. Despite the name change, Filipinos after 1899 are rarely called revolutionaries, even in the more balanced American textbooks. In my books, I use the term insurrecto whenever Americans are speaking because that term is true to the period. It is not a political statement (as you could probably tell by the tone of my posts).