[This is part three of a three-part series on the Pulahan War. Follow these links for parts one and two.]

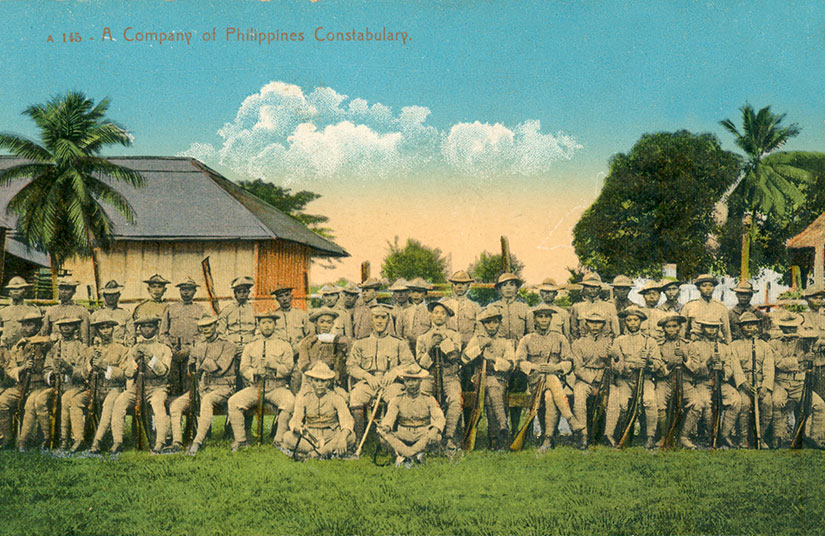

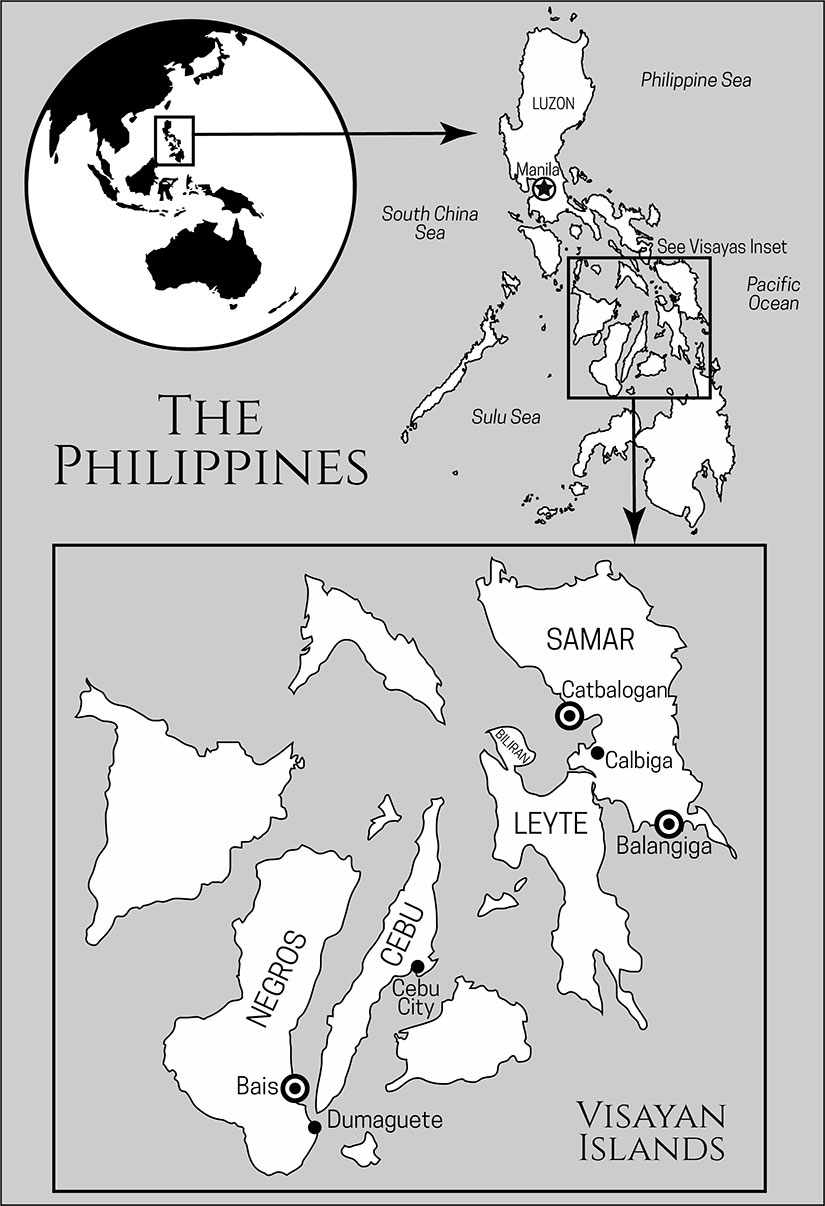

In 1905, General Allen of the Philippine Constabulary had to do the thing he hated most: he had to ask for help from the regular military and turn over responsibility for the east coast and most of Samar’s interior to Brigadier General William H. Carter, the commander of the Department of the Visayas, United States Army. According to historian Brian McAllister Linn:

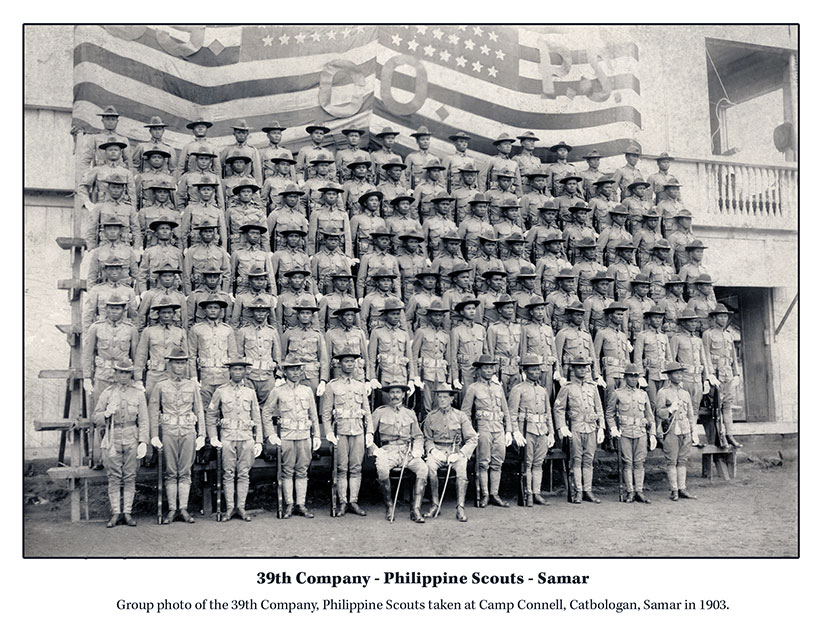

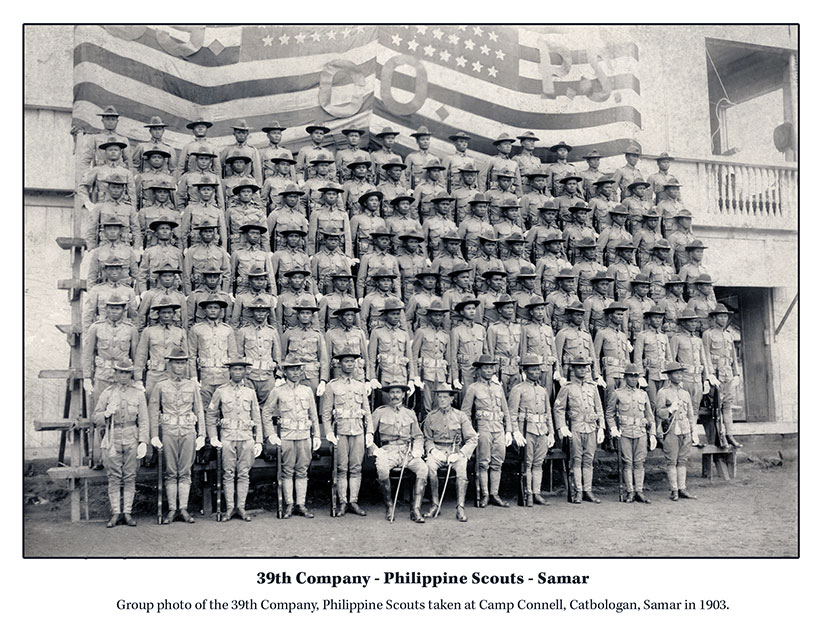

[B]y mid-1905, the entire 21st Infantry, three companies of the 6th Infantry, and two companies of the 12th Infantry were all serving on the island. A small flotilla of five gunboats and two steam launches ferried troops and supplies, protected towns and directed artillery and machine-gun fire against Pulahan concentrations. Perhaps most significant, the Army re-equipped its nine Scout companies with modern magazine rifles, providing them with the firepower to shatter massed bolo attacks (59).

It was about to be a whole new war.

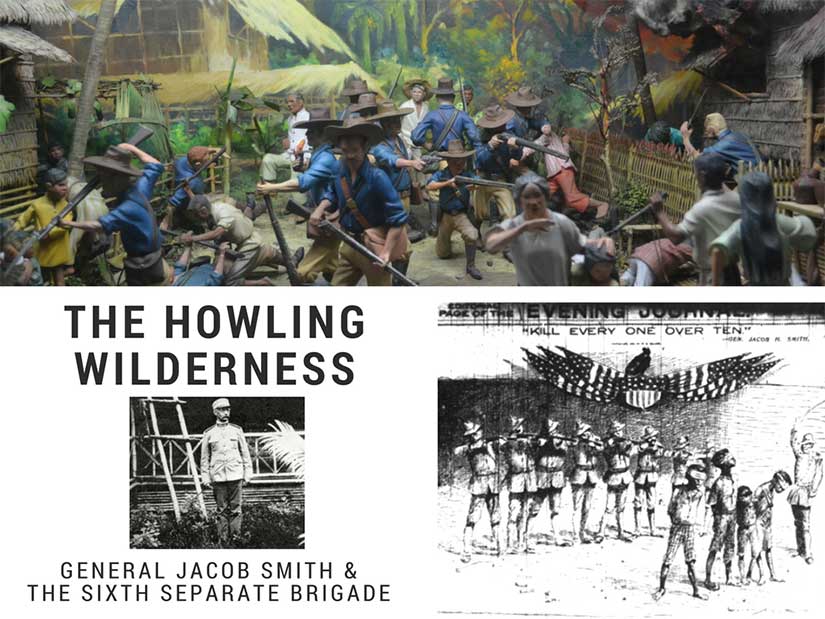

The Army was willing to bring their numbers to bear, but they had to be careful to avoid the kind of excesses that “Hell-Roaring Jake” Smith had used only years before. Smith’s tactics, which added fuel to the fire of rebellion, were exactly what Samareños expected from US Army regulars. Therefore, it was especially important that the newly arrived soldiers use restraint. Even the Manila Times warned: “If any exterminating is done, there is apt to be trouble. Dead men tell no tales, but they sometimes make an awful smell” (Quoted in Linn 65).

The Army also had to be careful to avoid the public relations nightmare of Bell’s tactics in Batangas, even if they had been effective. This time, the Army did not create concentrated zones along the coast, though sometimes farmers had to be relocated to get them away from Pulahan-dominated areas. The Army kept garrisons on the coast for security, but they used the rest of their forces in mobile sweeps. Unlike the later “search and destroy” missions in Vietnam, these patrols were not meant to kill Pulahans, or rack up a “body count.” They were designed to “penetrate into every place which might afford a hiding place . . . [and] keep them constantly moving and in a state of uncertainty to the whereabouts of the troops which will be practically on every side of them” (Linn 65). In other words, they were to set the Pulahans on their heels, to wear them down, and to starve them out—all without troubling the people of Samar and Leyte too much.

Moreover, unlike Bell’s campaign in Batangas, there was no “drop-dead zone” here. The Army made it clear that all care had to be taken not to kill any civilian unnecessarily:

In no case, at the present time, should persons who may be in the hills and have not yet come in, be killed, unless by their clothing or manner it becomes apparent they are Pulahans, for it is a well-known fact that the peaceable inhabitants of many barrios have, by force, been driven from their homes and their barrios burned by the Pulahans, in order that they might be made to work for them and gather food. It is the policy of the Commanding General and the Civil Government, to get these people back into garrisoned places and from under the control of the Pulahan chiefs, and when they present themselves to the authorities they should be well treated (Quoted in Linn 66).

Army patrol tactics were controlled and organized: soldiers marched single file through the jungle (in the mornings only) with fixed bayonets and a cartridge in the chamber. Odd-numbered soldiers faced one way and the evens the other. When attacked, they formed a compact mass around their civilian porters—these Filipinos were to be protected at all costs—and calmly fired (Linn 66-67). Conditions were difficult, but it did make for several romantic memoirs published in the early twentieth century.

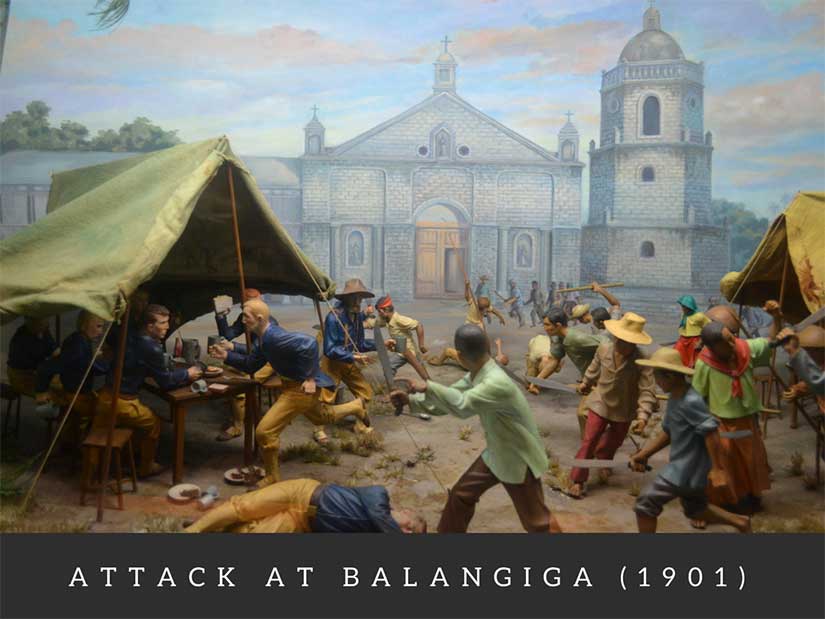

The military also set up good intelligence networks, and they did not turn down the services of former revolutionaries. Men who had taken part in the assault on Company C at Balangiga in 1901 were now on the payroll of the US Army quartermaster! Even the former mayor at Balangiga, considered the mastermind of the attack, helped the Americans against the Pulahans because they were threatening his hemp business (Borrinaga, G.E.R, “Pulahan Movement in Samar,” 251). As long as these authorities were seen as relatively honest and had good support among their people, they were used.

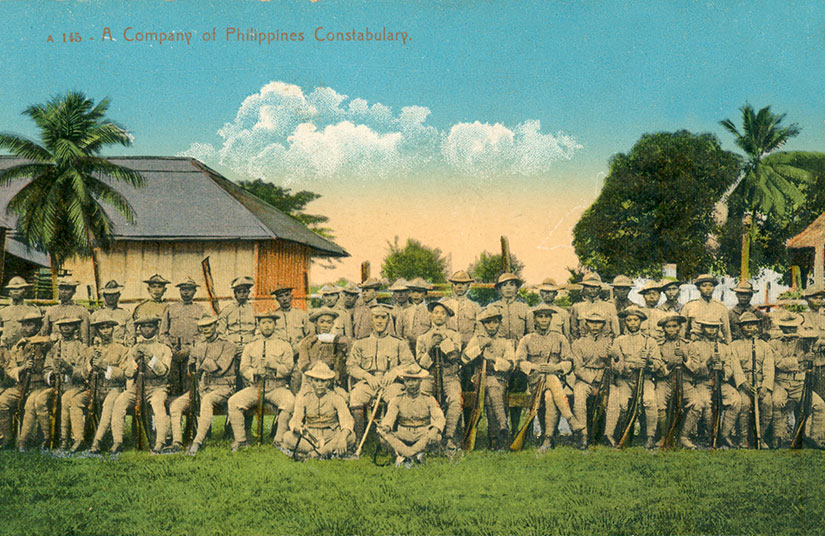

Not all credit for the American victory can go to the Army and Scouts, though. The civil government did not disappear, nor did the Constabulary—many of whom were the toughest fighters in an American uniform. One officer recounted the hardships: “The men were on continual campaign, with death in many painful forms ever lurking in the background. Discipline was strict, if not harsh, the pay was small, the clothing and equipment inferior, and the food poor even under ordinary circumstances” (quoted in Hurley 103). Another officer boasted of the “diet of python and rat and fruit bat” upon which his hardened constables lived (Hurley 4). But the greatest contribution of the Constabulary and the civil government was their emphasis on civil action, or the policy of attraction:

[Allen] took practical steps to remove the injustices which created Pulahanism, ordering the Constabulary “to investigate and correct abuses connected with trade in the interior . . . This is equally as important as capturing leaders and getting their guns.” With Manila’s support, Allen began construction of telegraph lines and planned a road across Samar that would end the mountaineers’ isolation, provide jobs for the destitute and allow troops access to the interior. . . . [also] Allen purged Samar’s civil officials, reprimanding or removing the excessively corrupt and inefficient (Linn 56-57).

In addition, the civil government suspended all land taxes for the year 1906, relieving the burden on farmers, who were struggling to replant their crops (Executive Secretary for the Philippine Islands 1906, 10-11). (But, as if their lives were not hard enough, there was a locust epidemic on parts of Leyte in 1906 (Borrinaga, G.E.R., “Pulahan Movement in Leyte,” 272).)

The Army got in on the action, as well:

. . . post officers distributed land to the refugees, encouraged crop cultivation, and punished corruption. . . . At Oras, which had been totally destroyed by the Pulahans, in one month soldiers distributed 2,728 pounds of flour, 2,100 pounds of beans and 15,260 pounds of rice to destitute Filipinos (Linn 59-60).

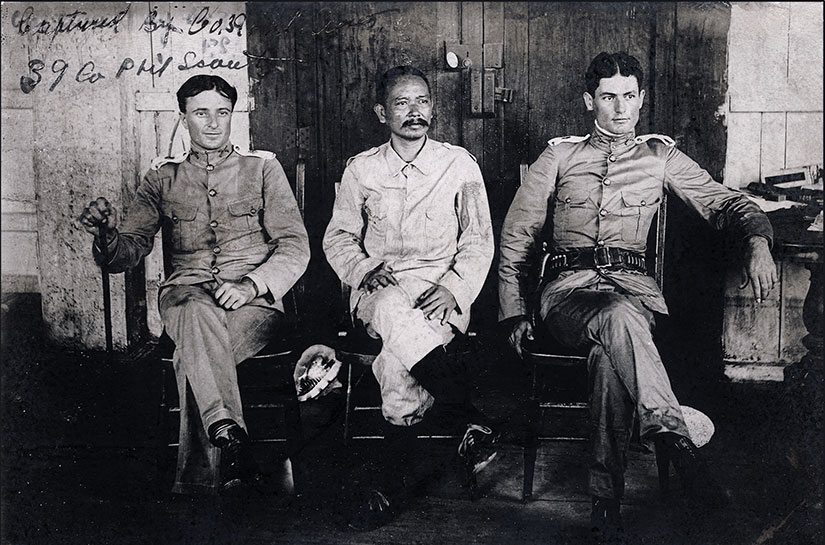

The pièce de résistance of the American small war effort was amnesty. In Feburary 1905, General Allen issued the following order: “All Pulahan lesser ranks who wished to return to their villages and accept civil authority would be granted immunity; lower-ranking officers could obtain immunity by surrendering a rifle” (quoted in Linn 56). In fact, the civil government was so serious about amnesty that once, when the Scouts were in hot pursuit of a Pulahan band who had burned and looted a town called Poponton, they chased them right into the hands of the civil authorities. Quickly, the Pulahans surrendered to the constables, and when the Scout commander heard of this, he was outraged. But Sheriff W. D. Corn said that Governor Curry had told him to accept surrenders and that he would “not be a traitor to them, although they may be murderers” (quoted in Linn 61).

This may seem like a short-sighted policy, but in the end the combination of carrot and stick worked. “Prisoners reported that Pulahans were dying of starvation; at one abandoned camp troops found every tree in a one-mile radius had been stripped of its edible foliage” (Linn 61). On the other hand, by “1 August [1905] nearly 4,795 Samareños had presented themselves to the authorities”(Linn 60). By May 1906, the Army declared northwest Samar “in as pacified or settled conditions as at any time since the insurrection” (quoted in Linn 63). While a few Pulahans continued to wander through the jungle until 1911, most of the popes of the movement were killed or captured in 1906.

This was a short, isolated war. There were few large battles, which had to have been terrifying, but they did not get the largest headlines. The Moro War being fought further south tended to dominate the papers—and with good reason, since the Moros were possibly even fiercer than the Pulahans. (They even inspired the Army to develop a whole new handgun to fight them: the 1911 .45-caliber pistol, still in use today.) And since the Moros were and are majority Muslim, that campaign is often seen to be more relevant today. However, unlike Samar and Leyte, the Moros of Mindanao were never appeased. They were silenced temporarily, yes, but the last fifty years of Islamic separatism (and recently Islamist terrorism) prove that they were not pacified.

The Pulahans were pacified. In fact, this war may be the only time the Americans fought a movement of religious extremists and won. (The Boxers were defeated militarily, but the Americans did not occupy Beijing long enough to really test their rule.) As millennial movements spring up all across the globe, will the secrets of Samar and Leyte make it into the handbook for the next war?

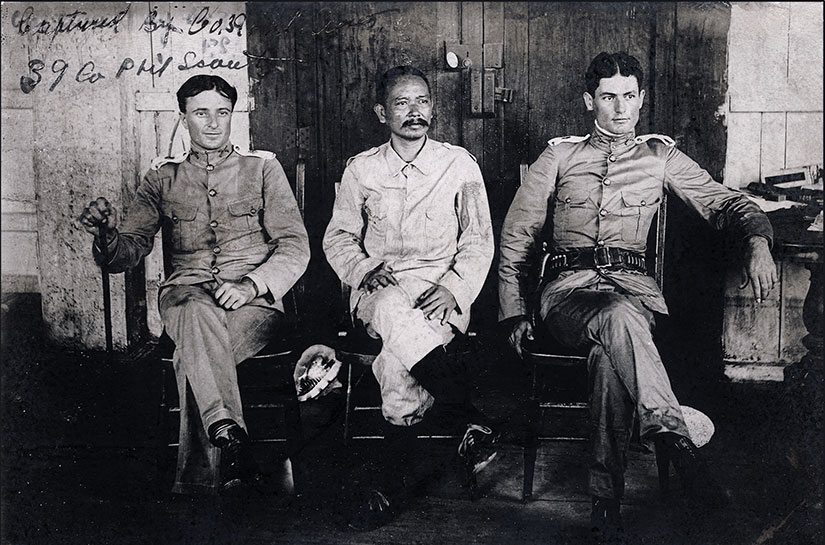

[Featured image was taken by and of members of the 39th Philippine Scouts dressed in captured Pulahan uniforms and carrying captured bolos. Multiply these men by several dozen, at least, to get the full effect of a Pulahan charge. Photo scanned by Scott Slaten.]