Award-winning author Joanna Shupe writes the men of Edwardian era New York like no other. While some are born to the Knickerbocker Club set, others are self-made titans of industry. But whether they are from Five Points or Fifth Avenue, they are all swoon-worthy. In Mogul, one will battle a real historical injustice: the racist immigration laws of the late nineteenth century.

She never expected to find her former husband in an opium den.

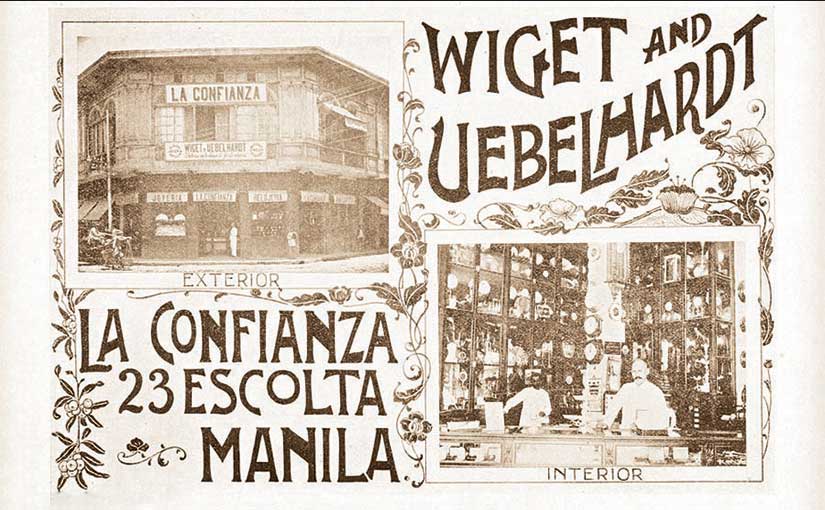

Thus begins Mogul, Shupe’s last book in the Knickerbocker series. Calvin Cabot, the son of humble American missionaries in China, has grown up to become one of the most influential men in America. Even with his lucrative newspapers and powerful friends, though, can he find a way around one of the worst laws of the Gilded Age—the Chinese Exclusion Act—to reunite a friend’s family?

In this post, Joanna Shupe answers our questions about the Chinese Exclusion Act and how she came up with the idea to work such substantive history into the conflict of her novel.

What was the Chinese Exclusion Act, and how will it affect your characters?

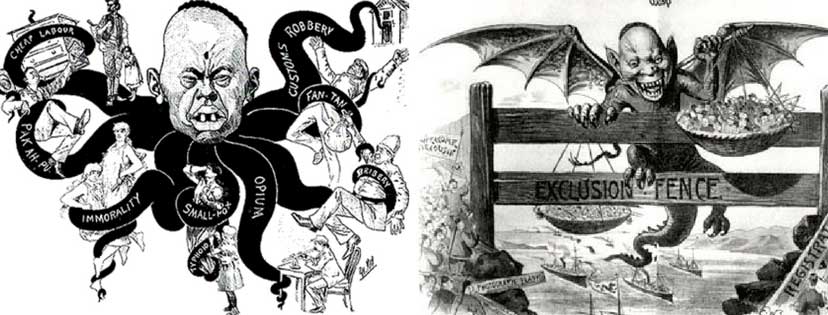

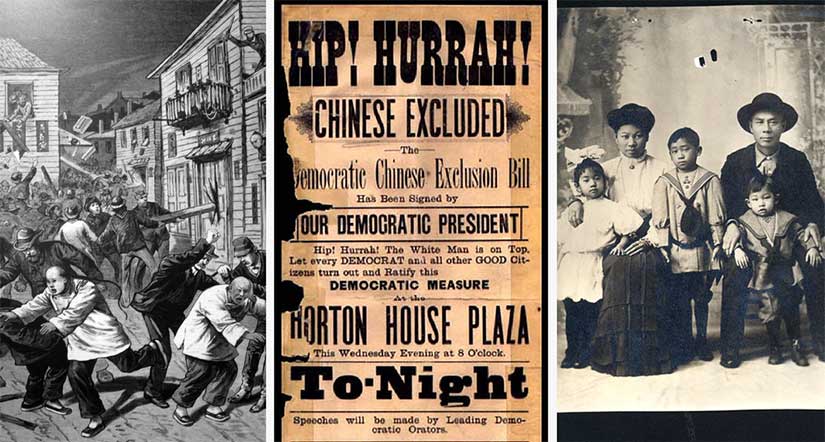

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, signed into law by President Arthur, severely limited the ability of Chinese men and women to enter the United States. It’s the most restrictive immigration policy the U.S. has ever had to date and wasn’t repealed until the early 1940s.

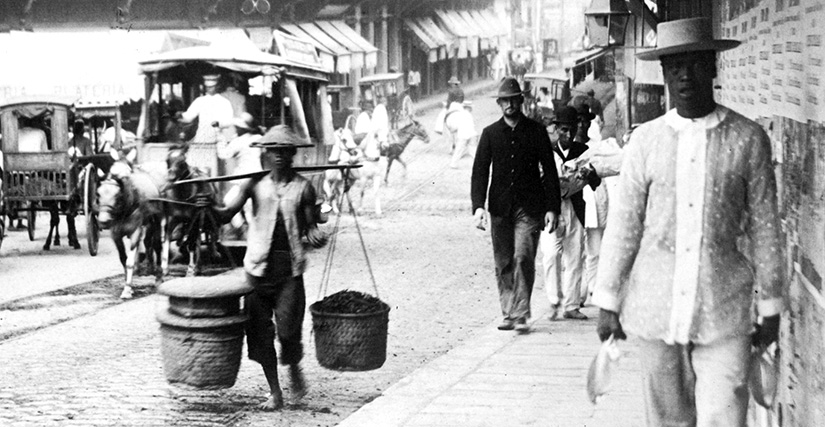

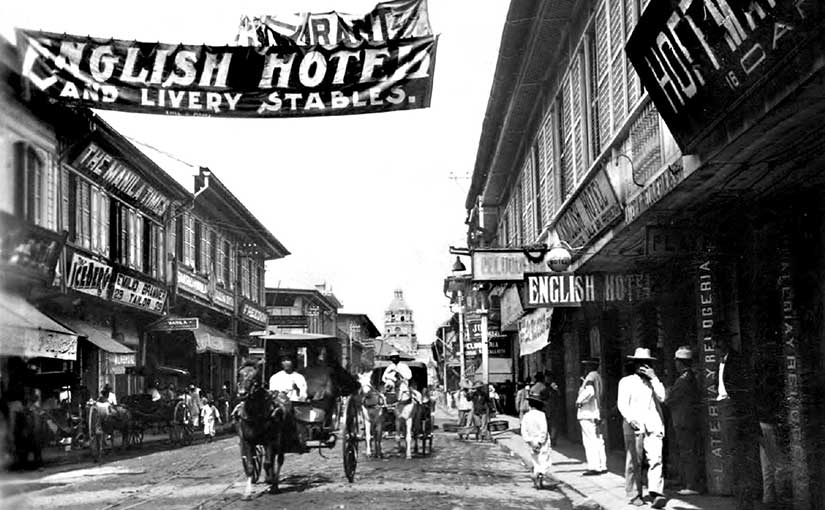

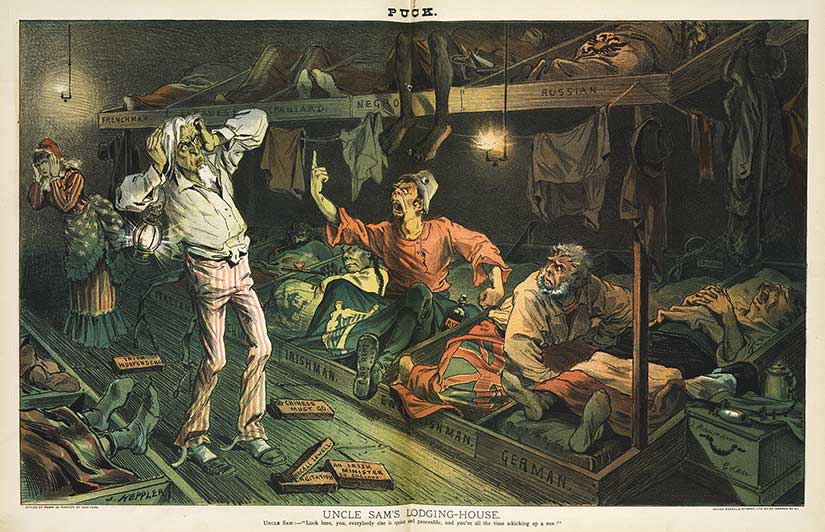

So why were Chinese immigrants singled out? In the 19th century, America was undergoing a massive transformation. The Gold Rush and the railroad expansion led to the need for cheap labor, and many Chinese immigrants (mostly men) were able to find jobs here. Gradually, anti-Chinese sentiment increased, polarized by a few politicians who used the Chinese immigrants as excuses for why wages remained so low. Their solution was to call for the banning of any Chinese laborer, thereby freeing up those jobs for American workers.

Starting in 1882, no Chinese laborer could enter the United States—and it was nearly impossible to prove you weren’t a laborer. Only diplomatic officials and officers on business, along with their servants, were considered non-laborers, so the influx of Chinese immigrants came to a near standstill. They also tightened the rules for reentry once you left, which meant families were separated with little hope of ever reuniting.

How effective were the Chinese Exclusion Acts at excluding the Chinese? For the last half of the 1870s, immigration from China had averaged less than nine thousand a year. In 1881, nearly twelve thousand Chinese were admitted into the United States; a year later the number swelled to forty thousand. And then the gates swung shut. In 1884, only ten Chinese were officially allowed to enter this country. The next year, twenty-six.

— “An Alleged Wife: One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era” by Robert Barde, Prologue Magazine, National Archives, Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1.

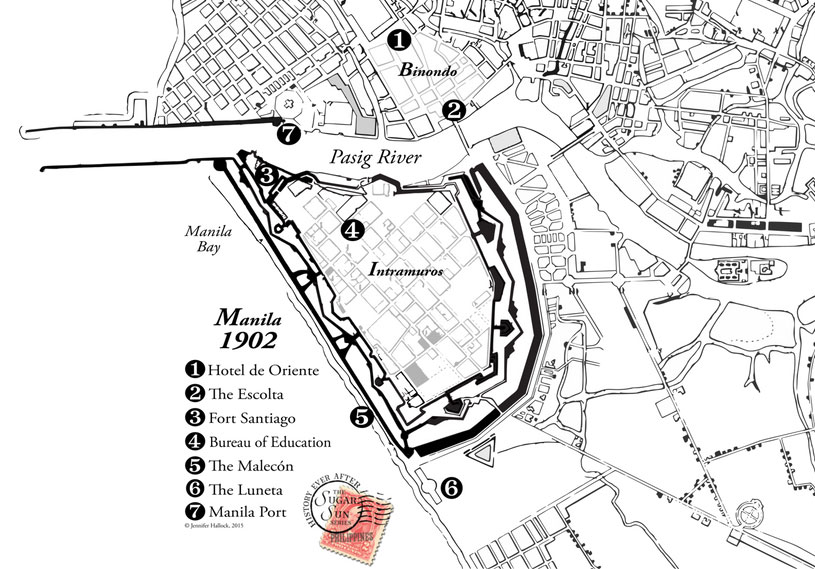

Mogul is set in 1889, and circumstances have separated the hero’s best friend from his wife, who is still back in China. His best friend is African American, so they decide to tell politicians and the government that she is really the hero’s wife. This presents a problem when the hero falls in love with—and impetuously marries—the heroine of the story.

This sounds like a pretty sobering piece of history. What inspired you to use the Exclusion Act as a central plot line in Mogul?

I started with this idea that my hero would be discovered in an opium den in New York City, so that was where my research began. I didn’t remember the CEA from my history classes, so I was floored when I discovered it. It’s tragic and racist, and yet seems still so relevant today.

As romance novelists, we love to find conflict for our characters. I thought the CEA might be an interesting way to drive the story forward. I wanted to both highlight the xenophobia of the CEA and use the forced familial separation to craft the plot.

What kind of research did you need to do on the act itself and on the Chinese-American community in general? Do you have any sources that you recommend for students and researchers?

I read quite a bit online about the CEA and the effects of the legislation. The 19th century Chinese-American community was fascinating to research. A good friend of mine is Chinese-American, and I peppered her (as well as her family) with lots of questions about the language and culture. They were all very patient and helpful.

I used mostly archives of The New York Times for tidbits about Chinatown, opium, and the Tongs, which is how I saw a mention of the game fan tan and began researching that. As with most historical research, you can fall into a rabbit hole pretty easily because it’s all so fascinating.

In a genre that some claim is about “escapism,” did you encounter any resistance to using this real history as a conflict in your book—either from editors, publisher, or readers?

I didn’t receive any resistance about this storyline, per se, but I’ve had readers tell me that they won’t read any historical set in America. The reason given is they can’t “romanticize” it the way they can with British history.

While I understand what they’re saying—after all, we’ve lived and breathed American history in school since Kindergarten—I don’t agree. We can’t assume we know everything in our history so well that we can’t learn something new or enjoy a compelling story. There’s so much history that isn’t taught—or isn’t taught well—and looking into the past gives us the clearest view of where we are today.

The Gilded Age is one of our finest eras…but also one of our nation’s low points. In each of the Knickerbocker Club books, I’ve tried to highlight some of the issues and problems as well as the opulence and wealth.