For a moment there, I wondered if I was getting to Sydney for IASPR at all. One of the legs of my journey was canceled, and it took two international calls to clear up the mess. (I think I’ve done it…we’ll see if I actually board a plane). When I hung up the phone, I thought to myself: “Gee, I would rather put the finishing touches on my History Ever After talk than grade those thirty-six exam essays waiting for me.”

(I would have probably also opted to fold laundry, clean out the fridge, and even scour the shower if any of those would get me out of grading. I feel bad about this reluctance because I teach really great students, and I love to see them succeed. But staring at such a large pile is disheartening.)

In any case, I procrastinated a few hours and updated the data on my slides. The last time I posted about my research, I only had about three months worth of market data to crunch. Now I have six. The results have not changed so much, even as Twitter has been alight with criticism of the lack of diversity in romance in general and historical romance specifically. But I should not get ahead of myself.

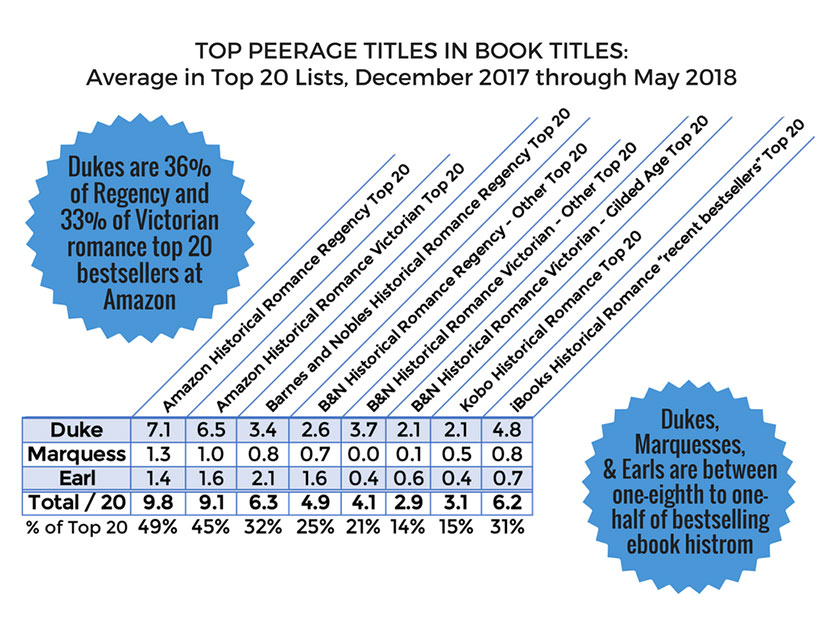

The dynamic duo of Regency and Victorian romance still dominates the industry. Of the historical romances that make the New York Times, Publishers Weekly, USA Today, Amazon, and Barnes & Nobles bestseller lists, 63% are set in 19th century Britain. And among online retailers, dukes are like kings:

With the royal wedding this past month, I understand the appeal of the royalty-slash-nobility happily ever after—though this wedding was far more inclusive and kick-ass than any Heyer book, I dare say. (While I am thinking of the wedding, let me give a shout out to my good friend Andres for bringing me a commemorative tin of shortbread. I may have been a little excited—ahem—when I received it. However, that “best by” date sticker has me confounded. I mean, really? The tin is what I want. That doesn’t expire. Who the heck cares about the shortbread?)

With the royal wedding this past month, I understand the appeal of the royalty-slash-nobility happily ever after—though this wedding was far more inclusive and kick-ass than any Heyer book, I dare say. (While I am thinking of the wedding, let me give a shout out to my good friend Andres for bringing me a commemorative tin of shortbread. I may have been a little excited—ahem—when I received it. However, that “best by” date sticker has me confounded. I mean, really? The tin is what I want. That doesn’t expire. Who the heck cares about the shortbread?)

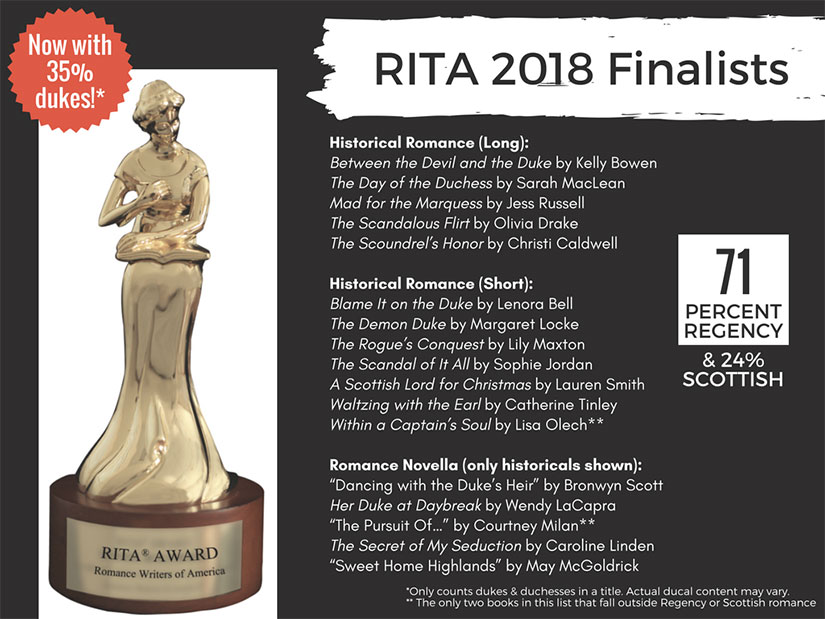

Anyway, I get it. I really do. But that still does not explain why dukes/duchesses appear in the titles of a third of the Amazon Regency and Amazon Victorian Top 20! (See the above slide.) About the same number of historical romance novel finalists in the 2018 RITAs have duke or duchess in the title. Not in the book; in the title!

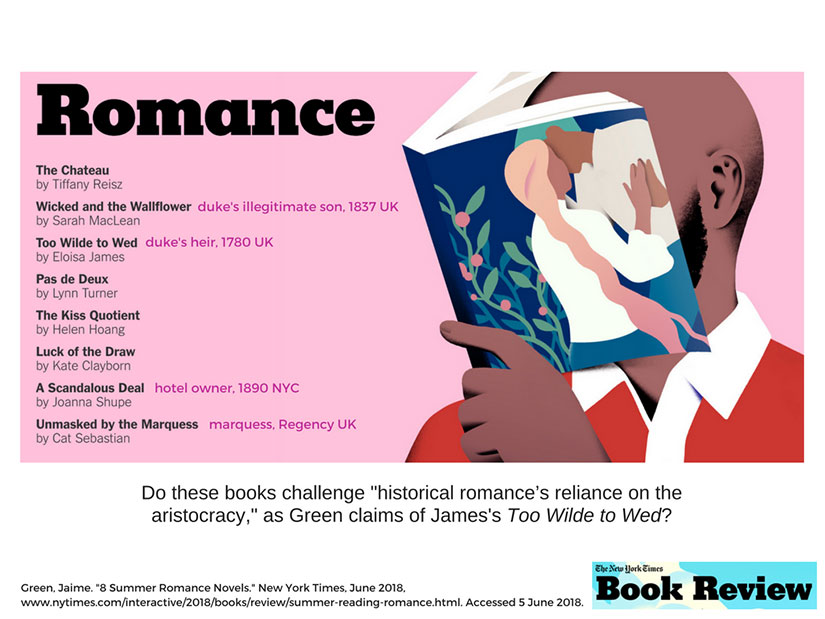

The New York Times Review of Books just put out a Summer Romance Reads list. The Review‘s new romance columnist (yes, they learned to ask someone who actually reads romance to write about romance) indicates a fresh trend: poking a stick at the genre’s “reliance on aristocracy.” I would have cheered this news loudly if it were not for the fact that 3 of 4 historical romance novels mentioned have peerage or peerage-adjacent heroes (2 duke offspring—one illegitimate—and a marquess). I have no doubt these books are great, and I look forward to reading them. I love all four histrom authors featured, and I have even interviewed Joanna Shupe on this very blog! And a few of these books challenge the chronotope in different ways—for example, Cat Sebastian has written a bisexual marquess and a nonbinary love interest. Cool!

I have no doubt these books are great, and I look forward to reading them. I love all four histrom authors featured, and I have even interviewed Joanna Shupe on this very blog! And a few of these books challenge the chronotope in different ways—for example, Cat Sebastian has written a bisexual marquess and a nonbinary love interest. Cool!

But I want commoner heroes and heroines who make things, heal diseases, and run businesses—and they did in history. Women did, too. The Times book reviewer writes: “In Regency England, the space [strong women] can eke is usually tiny, the size of a marriage and no more. Sure, there are outliers, but authors can only stretch historical constraints so far.” First of all, give me those outliers. Outliers make the best fiction! Second, this is true only as the Victorian era restricted women’s rights from what they had enjoyed before. So why do we love the 19th century so much?

Despite all these facts above, there are still strong women who made history, no matter the odds against them. And we might expand our understanding of women’s work to include the many household management and childrearing tasks that women had extensive control over. And you did see women in professional fields, such as education and health care. There are interesting stories out there.

And I do want to read all four of the historicals on the Times‘s review. The problem is not them, or any individual book. Any book is great if it is a good story well told. The problem is the effect of the aggregate. The overreliance on two chronotopes—19th century Britain (especially peerage heroes) and medieval England/Scotland—may distort readers’ view of history and make the market less friendly to diverse books and authors. This is a theme I will expand upon late this month in my recap of my talk, History Ever After. Stay tuned.