My favorite stuffed animal as a child was a weird-looking turtle named Snoozie. My bedtime stories were mostly Snoozie skits—half-Muppet Show, half Lion King—as written and performed by my father. When my beloved Snoozie tore a seam, my father stitched him up. The surgeon of the house did all the sewing. My father also removed my splinters with the tip of an eight-inch butcher’s knife. Since I could not stand to look at the knife, I watched his face as he concentrated. He never missed one, and it never hurt.

As I grew older, I loved to hear tales of my father’s training in medical school, like when he had to draw his own blood because his partner had passed out. He filled the syringe and handed it over when the other guy woke up. Another classmate devoted only one line in his notebook to each day’s lecture. Later, if anyone had a question about what was said a month ago in physiology, this fellow would look up the right dated line and reprise the professor’s entire hour-long talk verbatim, even the bad jokes.

Despite this steady diet of stories, my father did not believe in pressuring his only child to follow in his footsteps—not that it was much of a choice for me after college. I am a bit embarrassed to admit that I did not take a single laboratory science course after high school, and that omission would have been a problem on my application—in the 1990s. In the 1890s, not so much. Harvard Medical School accepted nearly all applicants. Well, all male applicants. The president of the university considered coeducation “a thoroughly wrong idea which is rapidly disappearing.”

Fortunately, coeducation did not disappear and, also fortunately, other medical schools at the time did accept women, including Ohio Medical University, where my next heroine, Liddy, will be trained. She will be one of about three women in her class of forty-nine. (My father went there too. By the 1960s, it was known as the Ohio State University College of Medicine. Go Bucks!)

Liddy will be unusual because she will have a bachelor’s degree when she starts medical school—something only eight percent of American medical students had in 1894, when she began. Typically those eight percent probably came from the bottom of their respective college classes. Scholars with promise went into teaching or the clergy. Physicians were considered “coarse and uncultivated . . . devoid of intellectual interests.” There was a real danger that too much science would “overcrowd” their limited minds. There were no written examinations at Harvard Medical School. None. In fact, that would have been impossible, one professor complained, because half of his students “could barely write.” He was not making a joke about doctors’ poor penmanship.

How could this be?

The Humoral System (Pre-Gilded Age)

Let’s talk first about what we know about what makes us sick. For far too long—from the ancient Greeks to the middle of the Victorian age—the European system of medicine described the human body as a balance of four substances called humors. If you had too much blood, the first of the four, it made you sanguine—courageous, hopeful, even amorous. Too much yellow bile turned you choleric, or hot-tempered. Black bile produced melancholic scholars, Shakespeare’s favorite. Too much phlegm slowed you down, made you apathetic. Your “sense of humor,” as it was known, even dictated which internal organs were most likely to fail you, like a combined CT-scan-slash-Meyers-Briggs personality test.

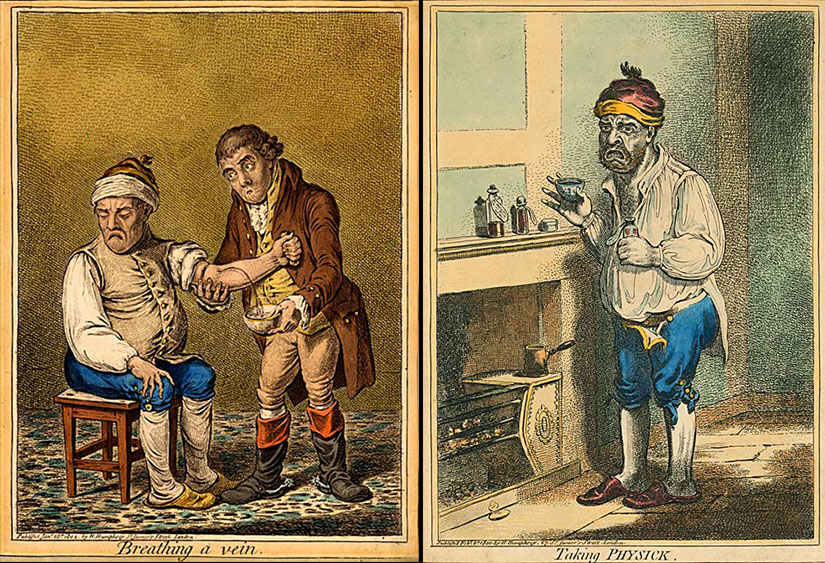

Blood was the only humor that could be spilled on command, so bleeding became a popular treatment for any imbalance. If you were sick in the eighteenth century, you headed off to your neighborhood barber-surgeon, maybe get a few teeth pulled while you were there. In 1793, when Founding Father Dr. Benjamin Rush faced a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia—then the nation’s capital—he treated one hundred people a day by draining two liters of blood per person. That’s about forty percent of the blood in their bodies! Half of Rush’s patients died. When George Washington fell ill from a throat infection in 1799, he was bled the same amount by his doctor. He died. Washington’s physician, like Rush before him, and like the barber-surgeons before them, used a specific scalpel named after a medieval weapon. It was called a “little lance,” or a lancet. A publication named The Lancet was and still is a leading medical journal. That’s like naming an education blog The Paddle.

Less extreme than the lancet were leeches, or parasitic worms. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Britain imported 42 million leeches a year, seven million for London alone. That was about three leeches per person, but it still wasn’t enough. One British doctor admitted to using the same leeches on fifty different patients in succession—not realizing that he was exposing that fiftieth patient to blood-borne diseases from the last forty-nine people he treated. No wonder Napoleon called medicine “the science of murderers.”

He should know. He had been given another favorite prescription of the age: calomel, or mercurous chloride, which was prescribed as a magical tonic for almost any ailment, from tuberculosis to ingrown toenails. It was another humoralist treatment: if you did not want to drain blood, you might choose purge your patient from both ends with powdered mercury. Among the many, many symptoms of mercury poisoning are tremors, loss of teeth, and amnesia. Oh, and death.

No, I’m not blowing smoke up your ass. Wait, did you ever wonder why we say such a thing? The biggest fear of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was, shockingly, not doctors themselves but their doctors burying them alive. George Washington’s last words were instructions not to conduct any funeral for three days, just in case his physicians were not capable of distinguishing between life and death. Apparently, he had not heard of the latest sure-fire test, a tobacco smoke enema. Blowing smoke through a tube into a person’s nether region was sure to animate any phlegmatic—even before Dr. Previnaire added a bellows, a hand-held blower like I use in my fireplace, to create his patented anal tobacco furnace. The Academy of Sciences in Brussels gave Dr. Previnaire a prize for his work (Bondeson 139).

This is not medicine, you say; it’s snake oil! Absolutely, another popular remedy.

There were some bright spots. British Naval surgeon Dr. James Lind discovered that oranges and lemons helped his sailors recover from scurvy, but he did not know why. He did not even know what Vitamin C was. Still locked into a humoralist mindset, he believed scurvy was caused by cold, wet sea air and a lack of exercise. And, yes, vaccination did exist at this time—in fact, a form of vaccination has been around for a thousand years—but originally no one could explain how it worked.

It was not until the population medicine studies of Pierre Louis in 1820s and 1830s France that people looked at the data and said maybe bleeding doesn’t work. Louis introduced a new way of examining the efficacy of treatment: looking at large numbers of similar patients and studying their reactions to different applications of medicine. It was the first baby step toward clinical trials, though it was not yet randomized and his sample sizes were not very large.

Bloodletting faded from life slower than the patients who were being bled. Despite a very public debate between doctors in the 1850s, the practice persisted in textbooks as late as 1942. One part of the appeal may have been its accessibility and affordability. There were bloodletters everywhere, and they were cheap “health care.”

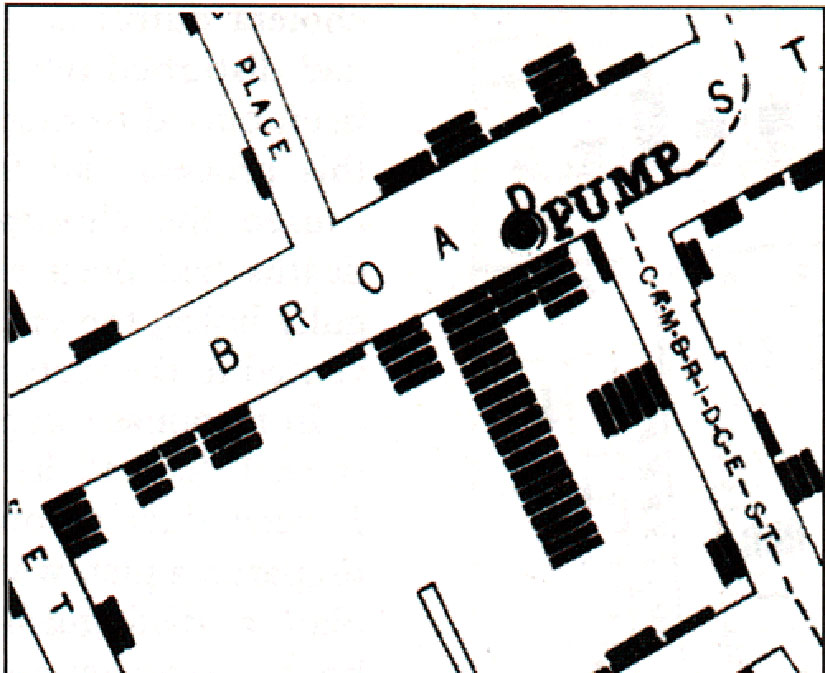

Another reason it persisted: no one had yet proven another theory of disease. All the pieces were there. Contagion was not a new concept: even as far back as the Islamic scholar Ibn Sina, there was an idea that disease could be spread by touch. Animalcules, or microscopic organisms had been seen as early as the 1670s. Dr. John Snow (not that Jon Snow) had shown it was not miasma, noxious urban gasses, that caused cholera but something the sick had passed to the water through their feces. Snow did not make this discovery with a microscope, though, but with a map showing clusters of cases around certain well pumps.

But Snow did not really change long-term thinking. The handle was reinstalled on the Broad Street pump in London a couple of weeks later, after the cholera crisis had passed. Maybe, they thought, Snow did not really know what he was talking about. Mysterious waterborne poison, indeed.

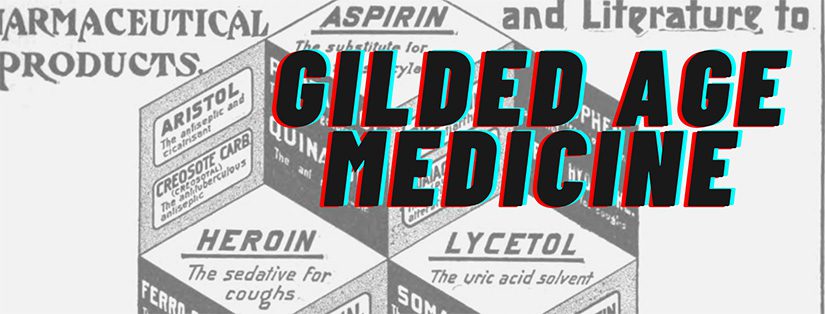

Gilded Age Medicine

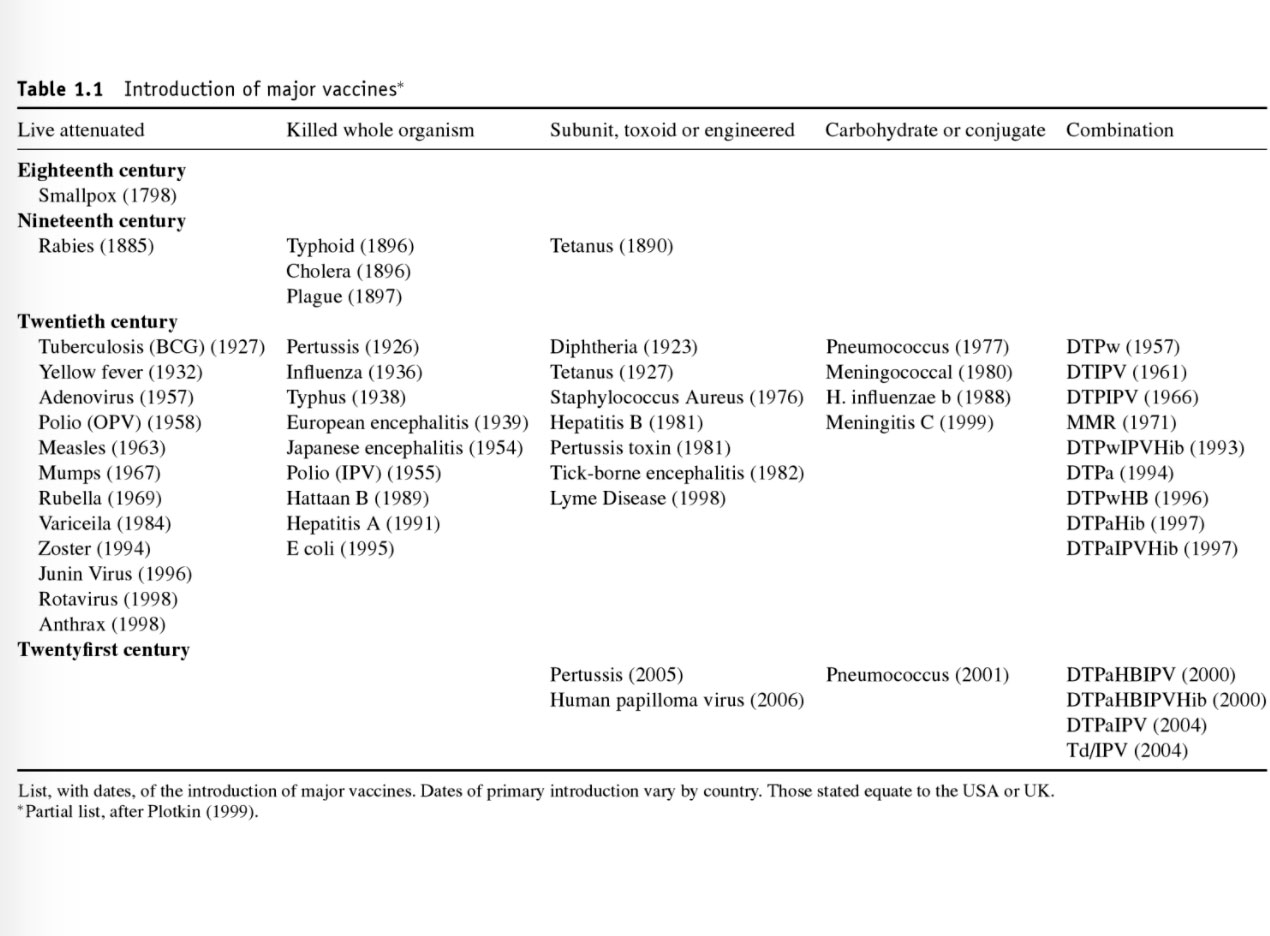

You cannot change the answers until you change the questions. And you cannot change the questions until you admit what you don’t know. What was in the air—or water—that we were not seeing? At the beginning of the Gilded Age, Louis Pasteur introduced an anthrax vaccine in 1881 and a rabies vaccine in 1885. Pasteur’s best frenemy, German physician Robert Koch, isolated the bacterium that causes tuberculosis in 1882. In 1884, he did the same for cholera. These were four of the worst disease bogeymen of the modern age. Modern bacteriology and immunology were born.

By the way, the man who introduced these two rivals, Koch and Pasteur, was Dr. Joseph Lister, the first surgeon to disinfect wounds and sterilize surgical equipment. You know his name as the root of the brand name Listerine. Yes, you are rinsing your mouth with surgical antiseptic. Please continue to do so.

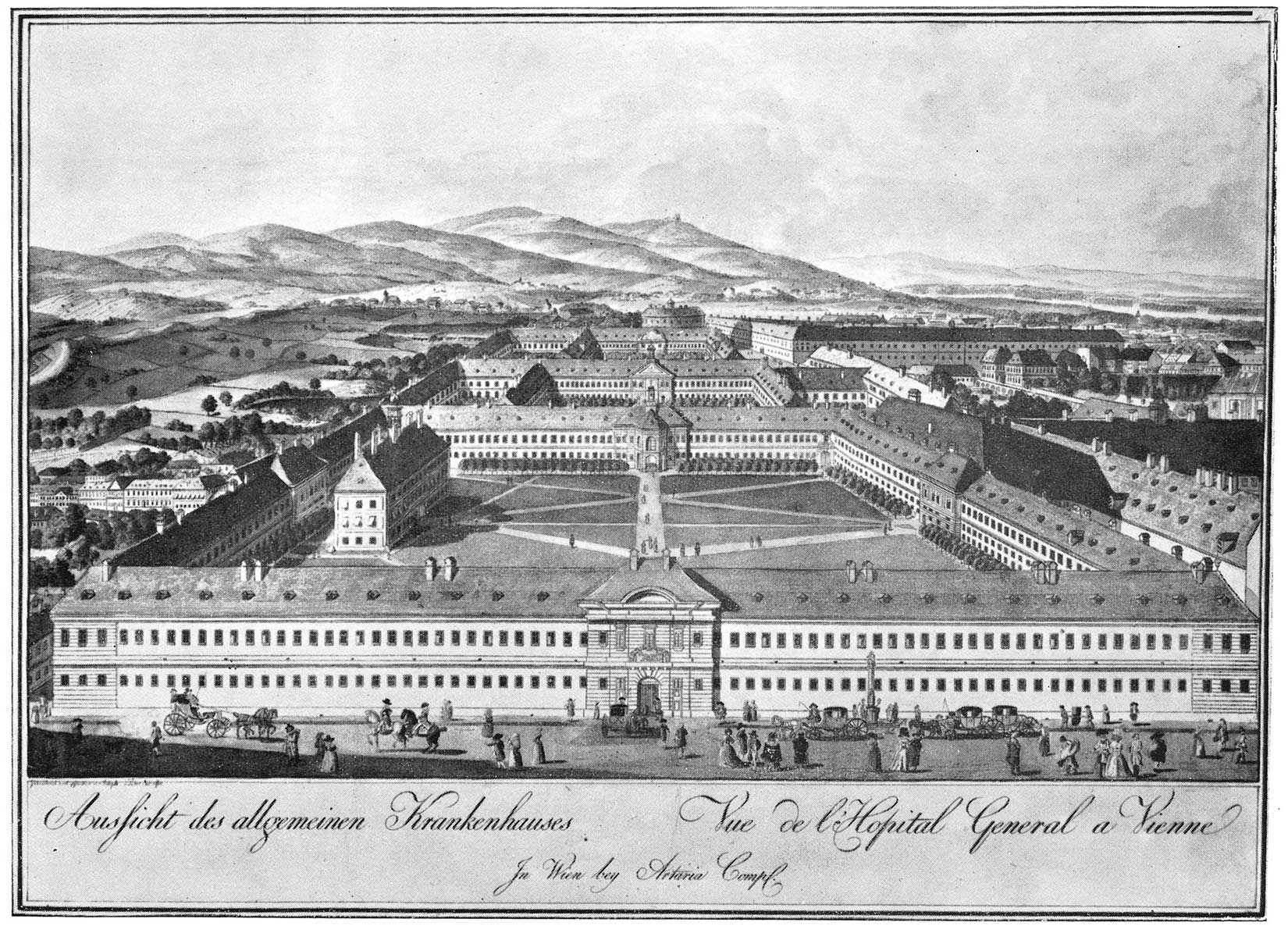

It would take time before the best and brightest of the American college set would pursue a career in medicine. And, like my character Liddy, if you wanted the best post-graduate education, you really had to go to Europe. While earlier in the century that may have meant Edinburgh or Paris, by 1890 that meant Germany or Austria, and in particular the Allgemeines Krankenhaus (General Hospital) of Vienna. (And you ate dinner at the Riedhof too!)

Back in the US, it was not until 1910 that medical education truly changed. Two of the richest men to ever live, John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, funded the Flexner Report, which was like an early US News & World Report ranking guide to medical schools—and like all of those publications, it was deeply flawed. The publication of the Flexner Report in 1910 is credited with creating the modern scientific medical school system in the US, but it also directly or indirectly caused the closure of many medical schools for women and African Americans. Those that had been coeducational reduced their admission of women, partly because they had a rise in male applicants. One study calls an unintended consequence of Flexner’s report “the near elimination of women in the physician workforce between 1910 and 1970.”

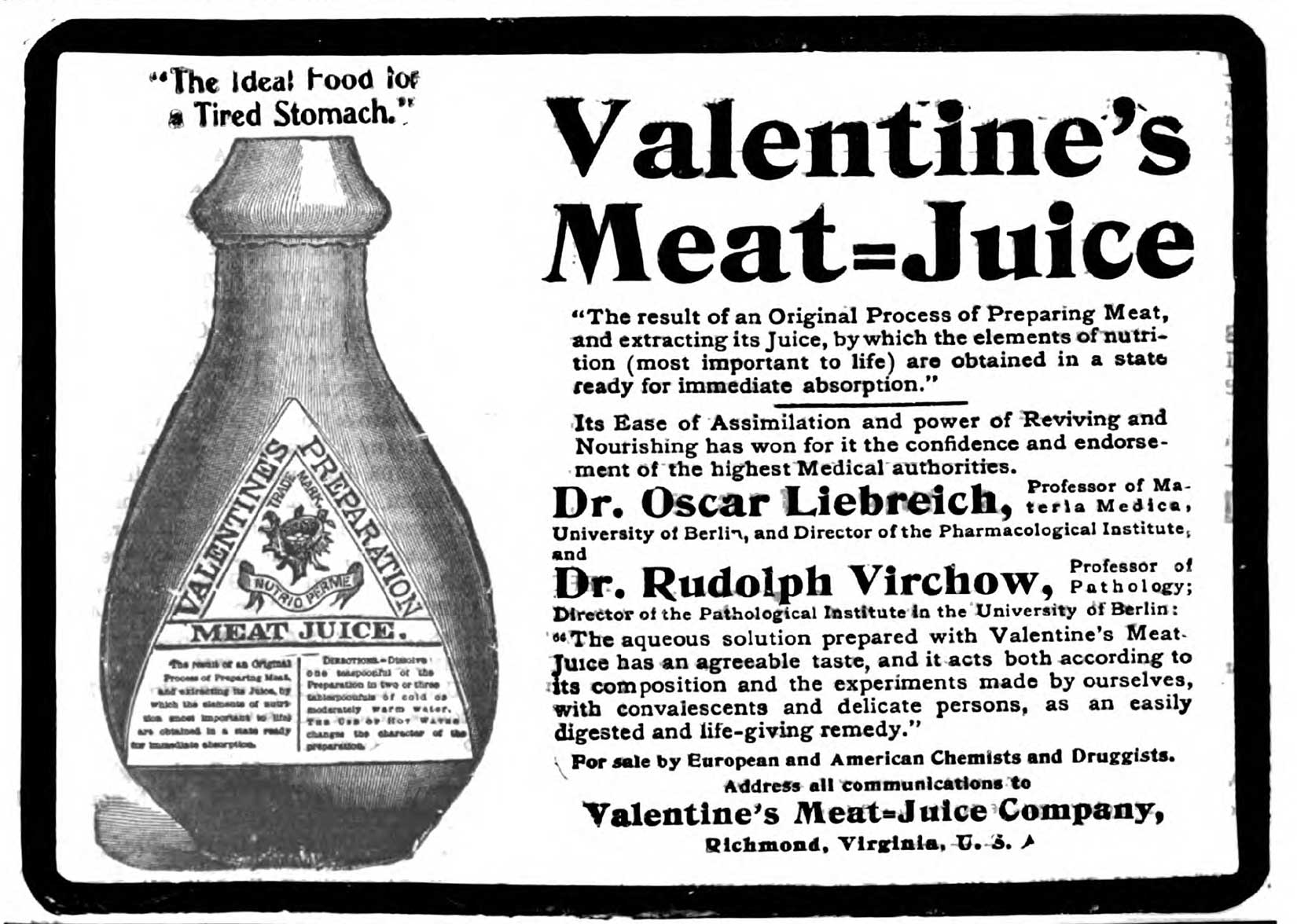

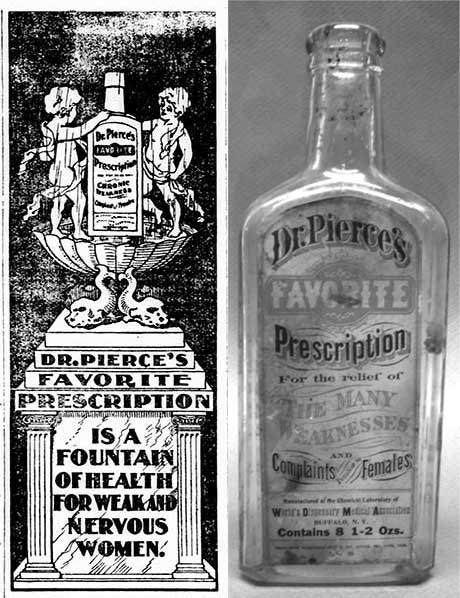

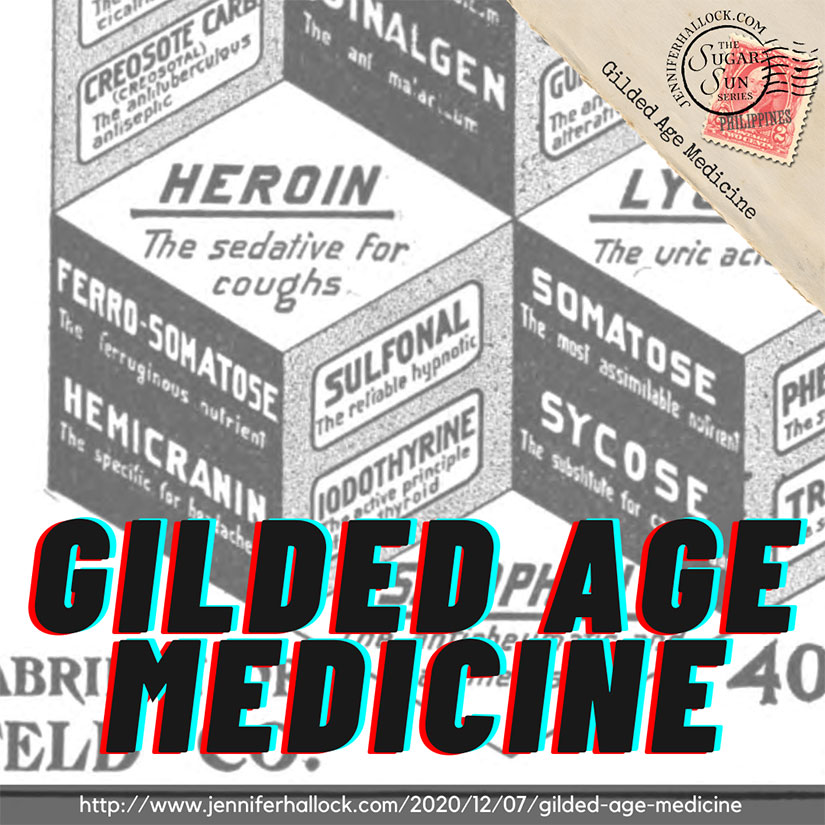

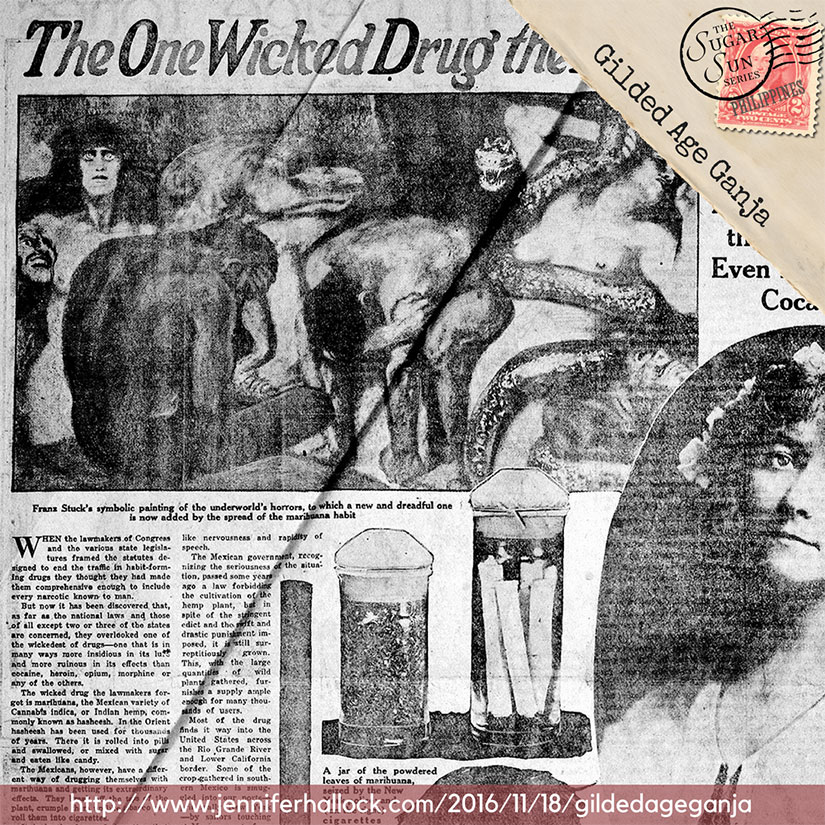

Nevertheless, the Gilded Age must have been very exciting to live through. Every day, it would seem, more diseases were being identified and explained. Notice that I did not say cured. Calomel was still popular in the early 1880s, as were chocolate-covered arsenic tablets. Aspirin existed, but no one knew how it worked until 1971! Cannabis was legal until the xenophobic backlash against refugees fleeing unrest south of the border after the 1910 Mexican Revolution, and then this effective pain reliever was demonized.

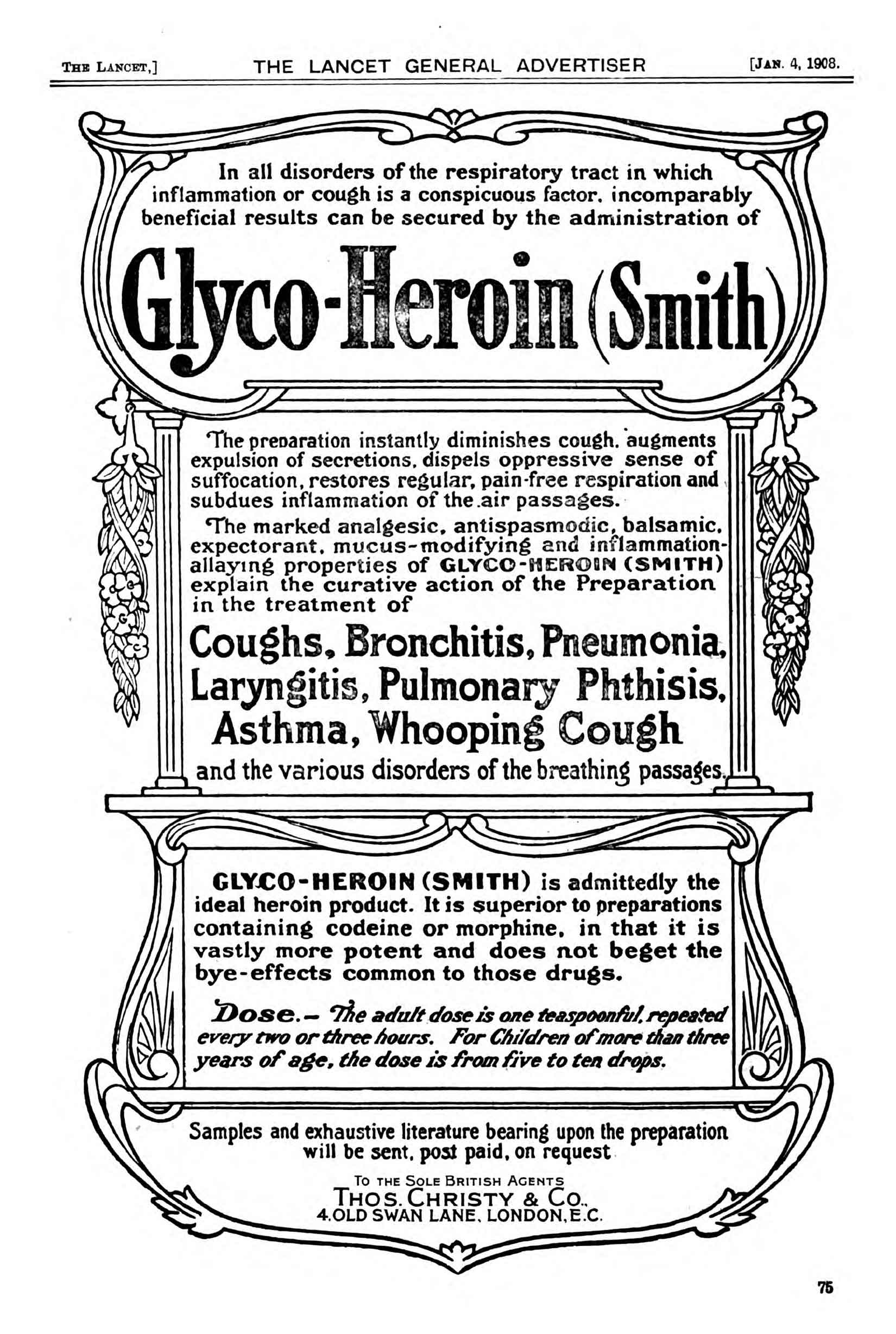

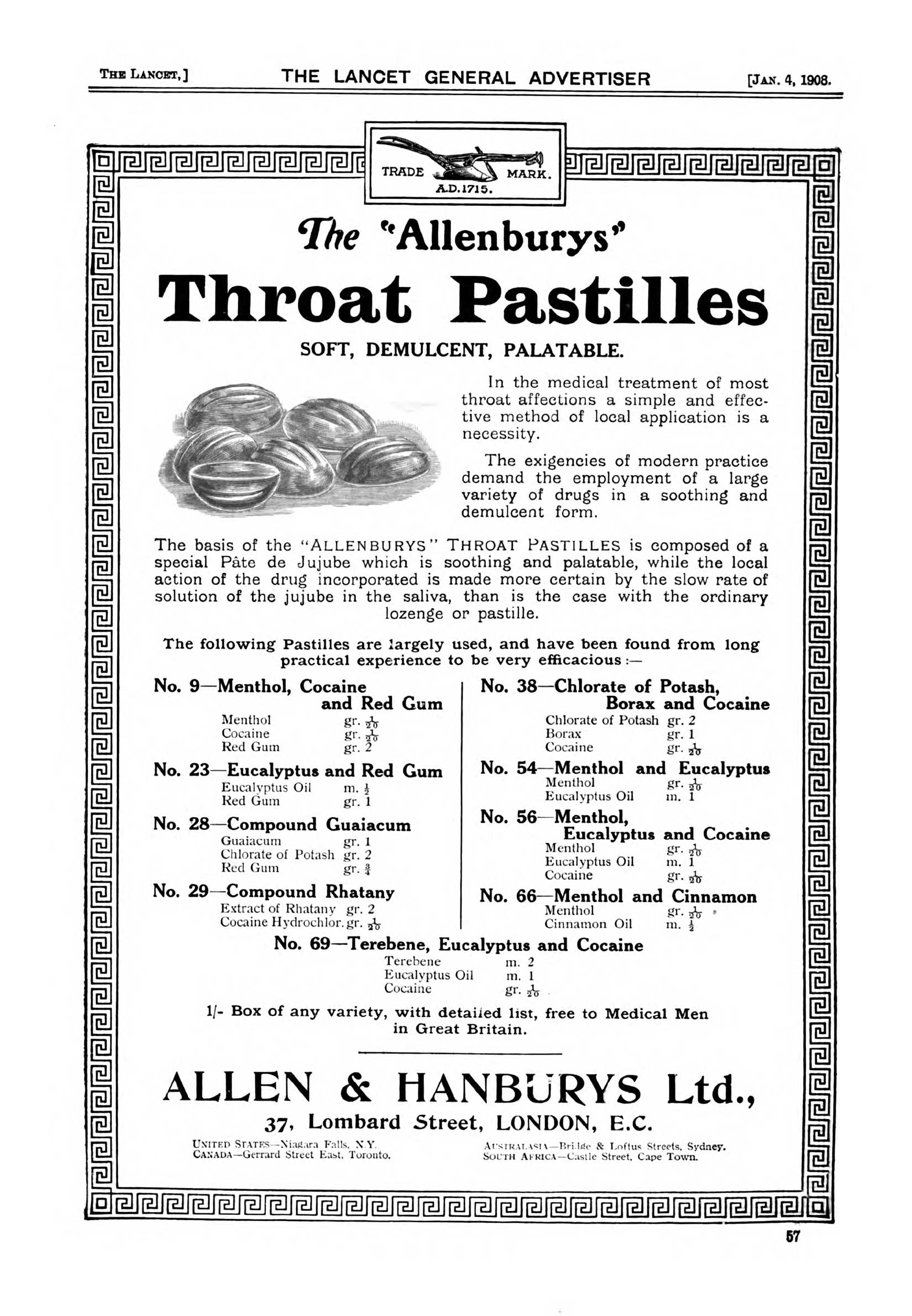

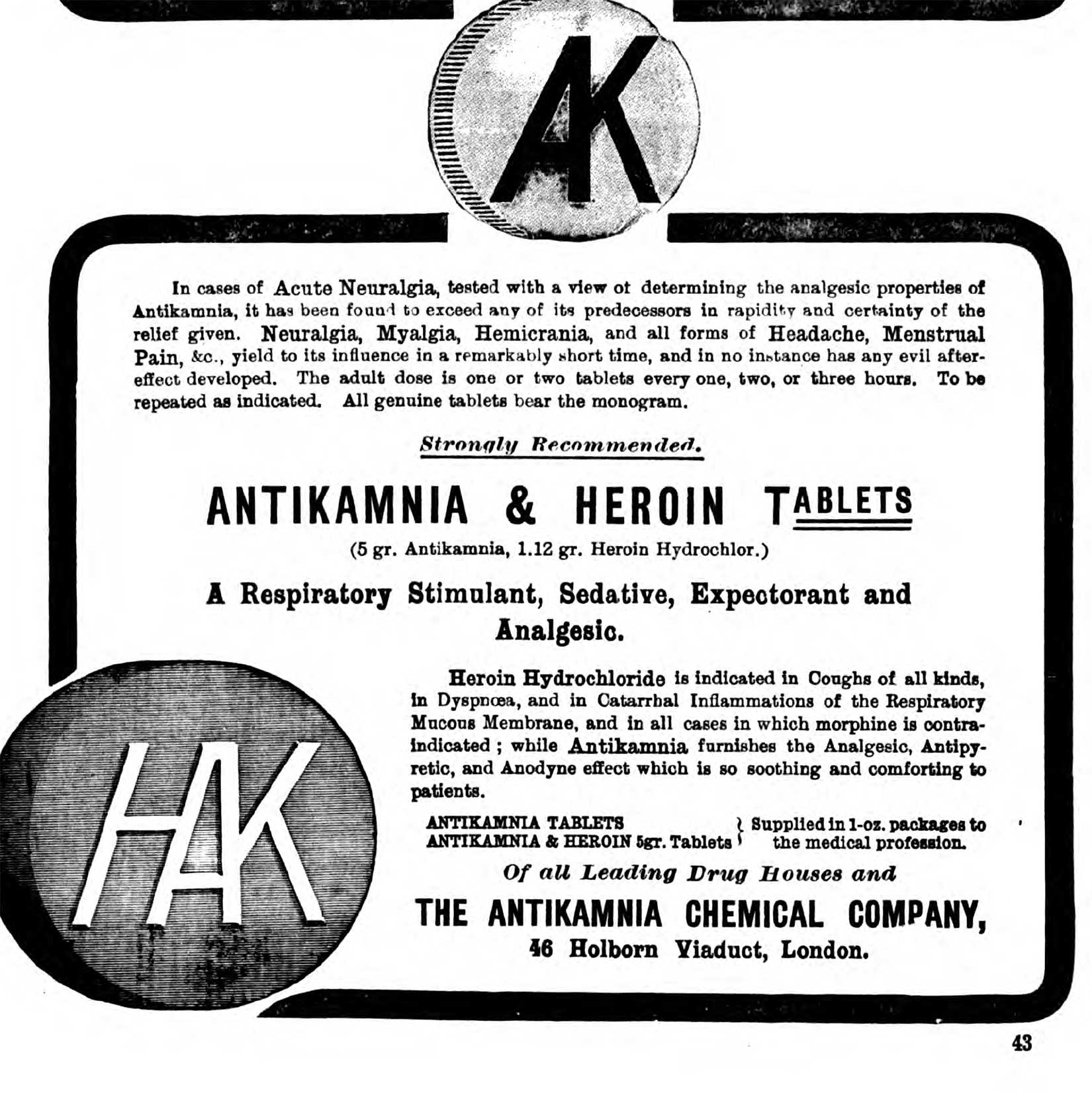

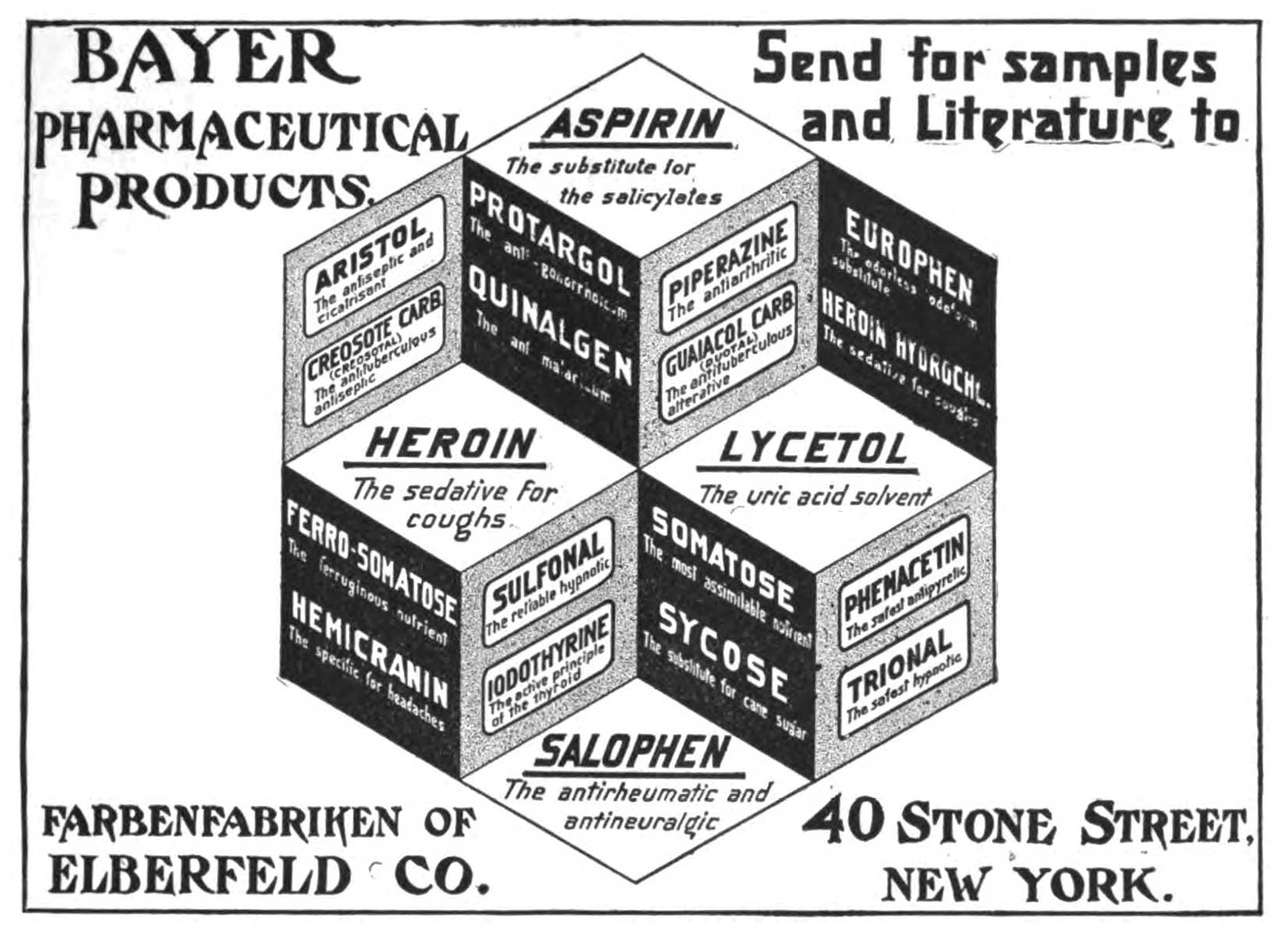

There still was no real anesthesia for surgery except ether and cocaine. Cocaine was quite handy, actually, and it was sold in lozenge form for toothaches. Bayer Pharmaceuticals introduced a new form of cough relief that they said was just as good as morphine, but not as habit-forming. They trademarked this miracle compound: Heroin. You could buy two vials for $1.50 from Sears, complete with carrying case and dosage instructions for children!

Paul Ehrlich was playing around with dye stains when he stumbled upon the inspiration for a chemotherapy treatment for syphilis that would eventually be known as Salvarsan. He and his assistant, Sahachirō Hata, introduced their “magic bullet” to the world in 1909. It was an actual medicine with laboratory-tested results, and really the importance of this fact cannot be overstated. There was no other treatment for syphilis at this time. (And masturbation was discouraged in the strongest moral terms. See more on syphilis in historical romance—or, really, the lack of it.) The administration of Salvarsan was technically complicated and cumbersome, though, and the disease had to be caught in time. Ehrlich had wanted to discover a “magic bullet” for what ailed us, but nothing was that simple. Eventually, post-Gilded Age, sulfa drugs were introduced (1930s) and penicillin and other antibiotics shortly thereafter, but old habits of calomel and bloodletting died harder than they should have.

Modern Parallels

Opioid addiction rates are not the only modern parallels to Gilded Age medicine. We still distribute poisons that would make the merchants of mercury blush. For example, botulism bacteria produce a paralyzing substance so toxic that one teaspoon could kill as many as a million people. You know it as Botox, a medically recognized treatment for Cerebral Palsy and chronic migraines. Or you might have it injected into your face to smooth your wrinkles. No judgment.

Progress is not always a straight line. Leeches and maggots are making a comeback—raised in sterile conditions, fortunately, and shipped to an intensive care unit near you. The leech releases an enzyme that keeps blood vessels open, which is essential in reattachment surgery particularly in fingers and toes. Maggots are good for recurring ulcers of the skin caused by drug-resistant infections like MRSA. Maggots only eat dead tissue—as long as you get the right type—and also release an enzyme that promotes healing. And even bloodletting, or phlebotomy therapy, may be used today for specific diseases of overproduction of red and white blood cells and excess iron.

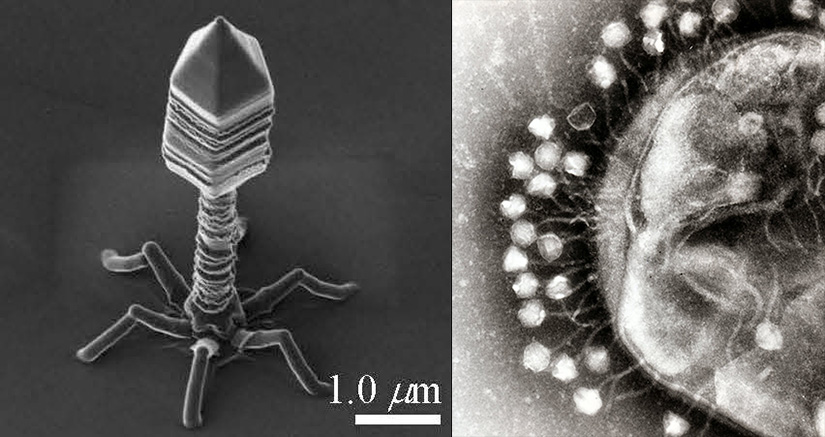

The medicine of World War I is also making a comeback. Bacteriophages are viruses that destroy bacteria. Honestly, they look like creepy spiders from a horror movie. They are hard to keep alive in transport—which is why they were tossed aside when antibiotics were discovered—but in an era of resistant superbugs, they may be the answer.

My father is now retired from stitching up humans and stuffed animals. There are many talented, highly-trained, and impressive women and men who have taken his place. This Thanksgiving I am grateful for them all, from emergency room nurses to the scientists behind messenger RNA vaccine development. But if this somewhat sordid tour of medical history has taught us anything, it is this: whether you are doctor or patient, teacher or student, we need to keep in mind the wise words of 12th-century rabbi, scientist, and physician Maimonides: “Teach thy tongue to say ‘I do not know,’ and thou shalt progress.”

Even Maimonides should have trained his tongue better. After all, he believed in bloodletting.

Further Reading

Want to know more about the history of medicine? I used a collection of podcasts introduced in my previous post, and I cannot recommend them highly enough! For more on sex education manuals of the time, check out my random sampling.

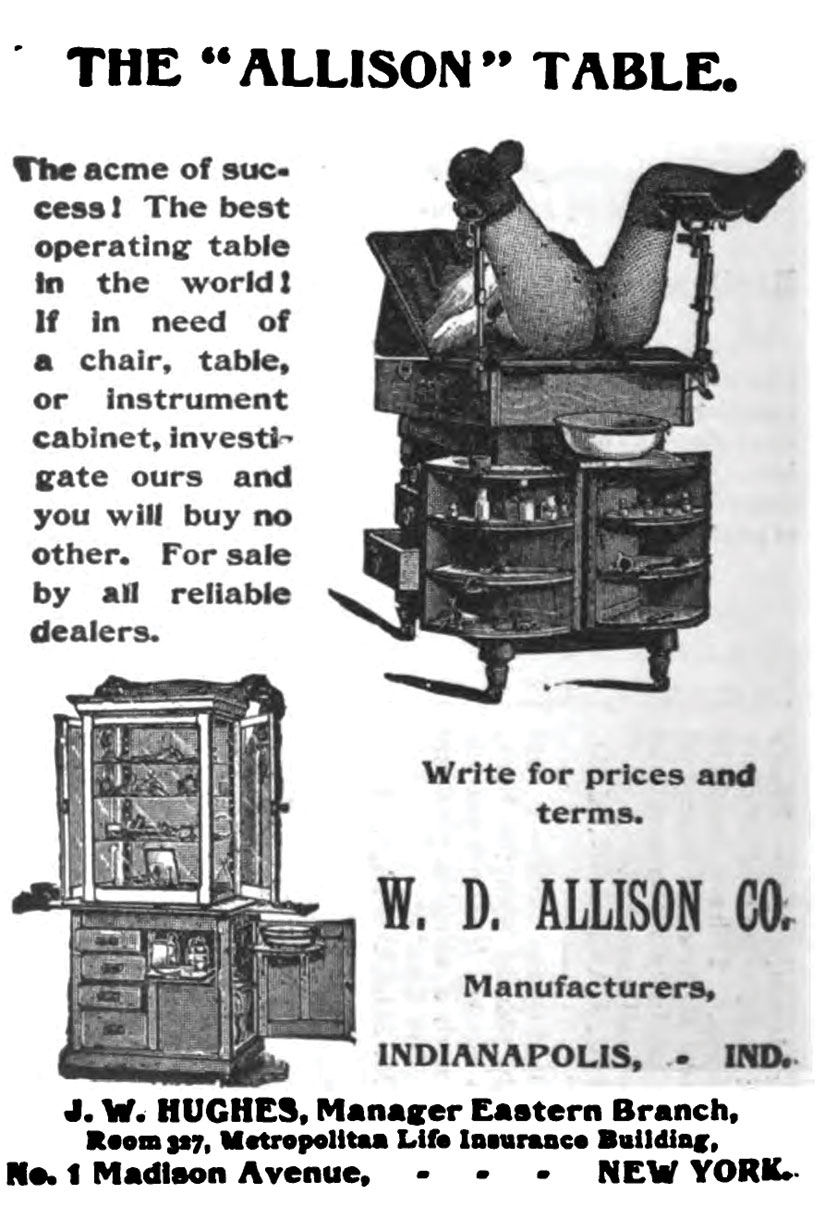

More Medical Advertisements from the gilded age