I spent many Thanksgivings in the Philippines, and it was great. We had some fun parties, including one at our farm.

The only drawbacks were that it was a normal workday for me, and I did not get to watch football live all day long. This year I have a little time off: my exams are graded and student comments written, so wheeeee! And, like in recent years, we will celebrate “Friendsgiving” in New England with two vegetarians. Meh, I’m not big into Turkey, anyway, so I’ll take it. But how did soldiers far from home celebrate in 1899?

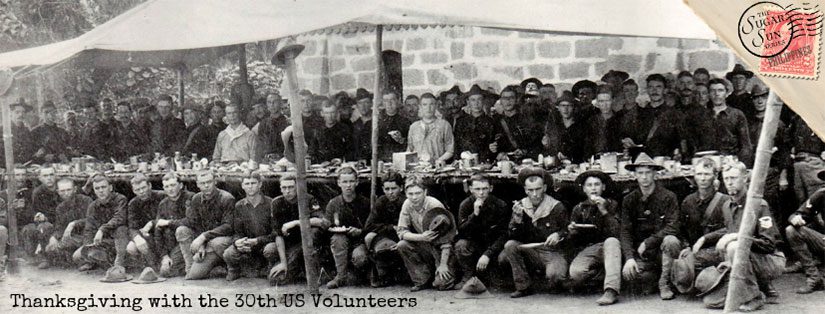

30TH VOLUNTEER INFANTRY REGIMENT: Thanksgiving dinner for the men of Company “D”, 30th Volunteer Infantry Regiment in the outer Manila trenches at Pasay. The photo was taken on November 24, 1899, and shows the men sitting down to their meal laid out on a long bamboo table protected from the hot sun by a canvas awning. The Soldiers from Company “D” are wearing their blue Army service shirts and campaign hats. Some men wear a special red kerchief around their necks, which later became a hallmark of the regiment and earned them the nickname, “The men in the crimson scarves.” Company D was lead by Captain Kenneth M. Burr throughout their tour in the Philippine Islands. Photo and caption uploaded by Scott Slaten on the Philippine-American War Facebook Group. (If you are interested in this war at all, you really should follow this group. It’s free, the discussions are strident, and the photos are amazing.)

What would it have been like in November 1899, just as the Philippine-American War was moving from conventional conflict to guerrilla war? Yes, the American military had more men, more guns (though not necessarily better ones), and more bullets. And without General Antonio Luna, who had recently been assassinated, the Philippine forces lost one of its greatest strategists. But Aguinaldo made the decision to disband his forces for an unconventional conflict, and that gave the Filipino revolutionaries a new edge. For the American troops, they had to realize they might not be going home anytime soon.

While I can easily say that I do not support America’s imperialist cause in this war, none of that changes history. I wonder what was going through these young men’s minds on this day.

30th INFANTRY REGIMENT, USV – Thanksgiving Day at Pasay, outer Manila trenches with the 2nd Section, Company G, 30th Infantry Regiment USV, November 1899. The photo shows the men with their Krag rifles stacked on the street of their small camp. Note the sign for the 2nd Section in the middle of the photograph. These photos are also nice reminders that even in war, people celebrate holidays and birthdays. They even fall in love. (That’s where we historical romance authors come in, as Beverly Jenkins so often reminds us.) But what these men’s families wanted to know was not whether they were having a good time, but when they would be coming home. They would not get their answer for another whole year:

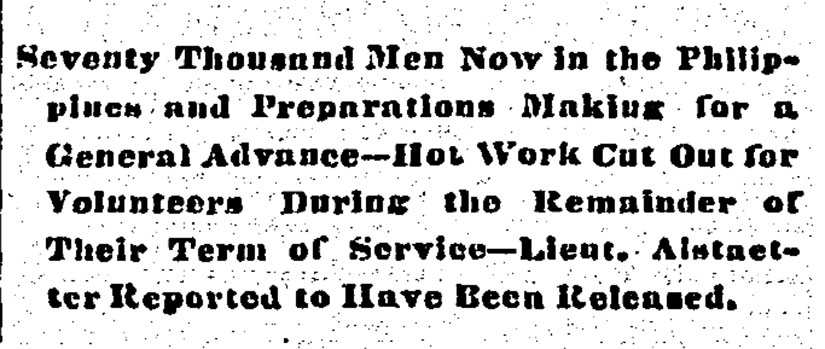

This was from the November 22, 1900, edition of the Washington Post. Since most of these soldiers had originally volunteered for what they had thought was a brief war in Cuba, this was probably a relief. Some did re-enlist as regulars, though, which meant a much longer commitment.

For you Sugar Sun readers out there, here’s a little Thanksgiving tidbit for you: Pilar Altarejos, daughter of Javier and Georgina, was born on Thanksgiving 1903. I thought that was appropriate. The couple could be thankful for being together— how romantic!—and I thought it would get Javier’s nationalist back up a little.

Hopefully, wherever you are, I hope you have a great week. The best thing about this holiday is the reminder to be grateful for something. I am grateful for so many things, but I want to add you, my readers, to that list. Thank you for reading and for following the Altarejos clan through all its ups and downs. More adventures in love will be coming, I promise!