The Definition

What is a bangka? It depends on whom you ask.

Javier was not thrilled to be out on the water at such a late hour, even if the moon was bright and the rowers competent. Had this been a pleasure tour, the hacendero would have had no complaint, but tonight he wanted to get on with it or go home. As if they could read Javier’s mind, the rowers abruptly beached the banca, hopped out onto shore, and dragged the vessels away from the water line.

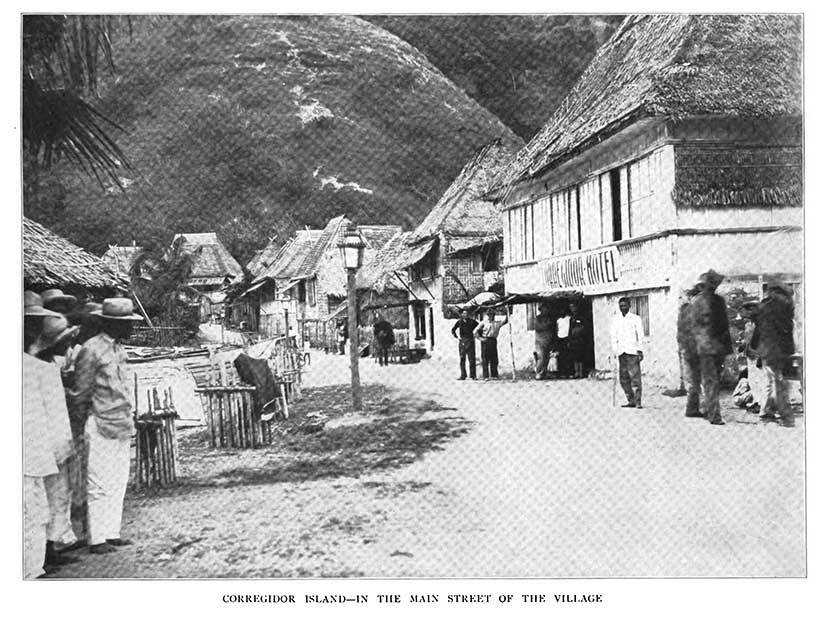

As you can probably guess from the context, banca or bangka means boat—specifically a double-outrigger canoe. If you have visited anywhere outside Manila, you have probably taken a bangka. When I first drafted Sugar Moon, Ben and Allie did a fair amount of bangka travel in Samar.

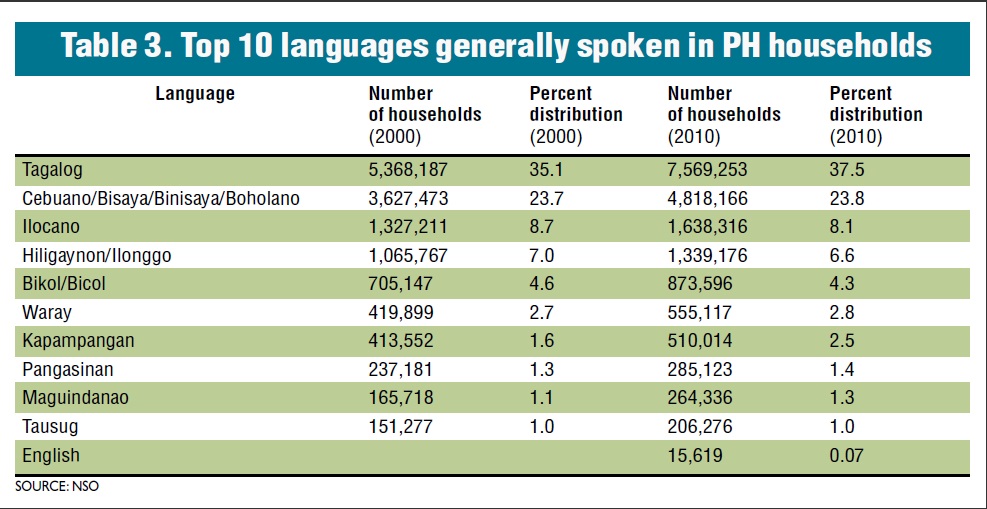

But here’s the problem: bangka may mean outrigger canoe in Tagalog and Cebuano, but I found out that it means cockroach in the Waray language of Samar, Biliran, and parts of Leyte. While strange stuff happens in Sugar Moon, riding a cockroach through the surf is a whole new level. So I took the word out and used boring old English.

The Implication

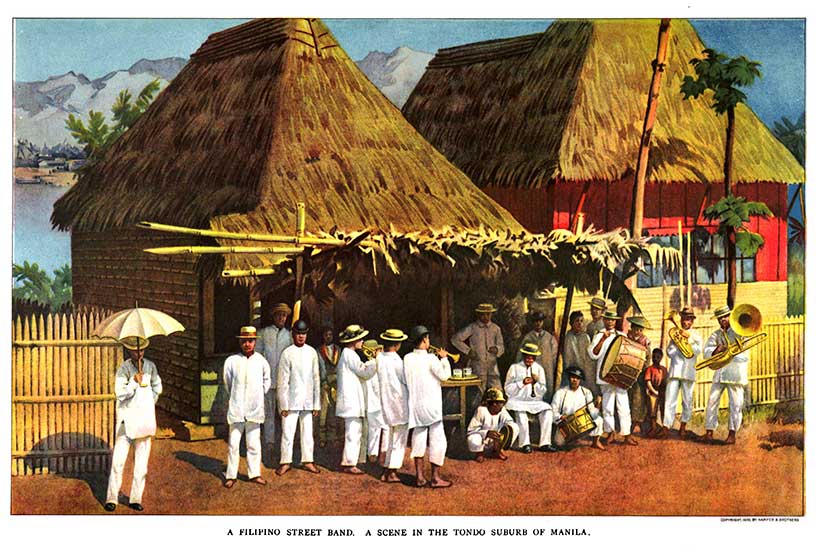

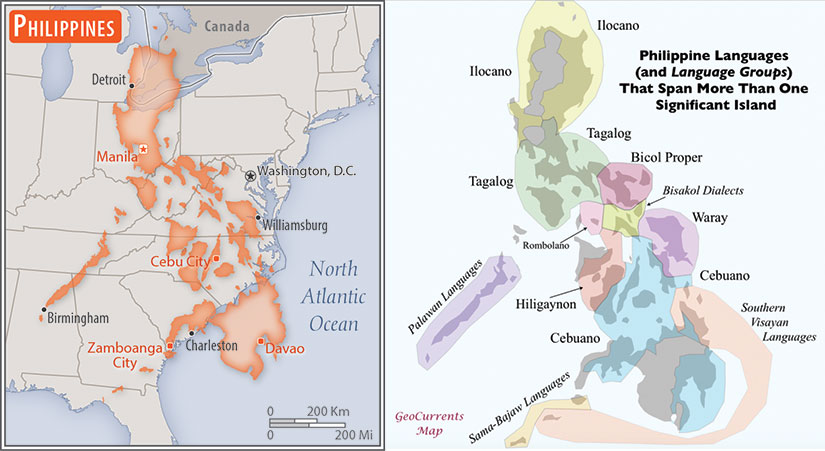

This brings up an important point about the Philippines: it the tenth most linguistically diverse country in the world. There are eight language groups, 19 local languages that can be taught in early childhood education (from kindergarten to 3rd grade), and now 200 total languages identified. Such linguistic abundance makes geographic sense. The Philippines is an archipelago nation of 7,641 islands, and it is so spread out that it stretches almost from Seattle to Los Angeles. No wonder one language could not dominate. But this doesn’t make things easy.

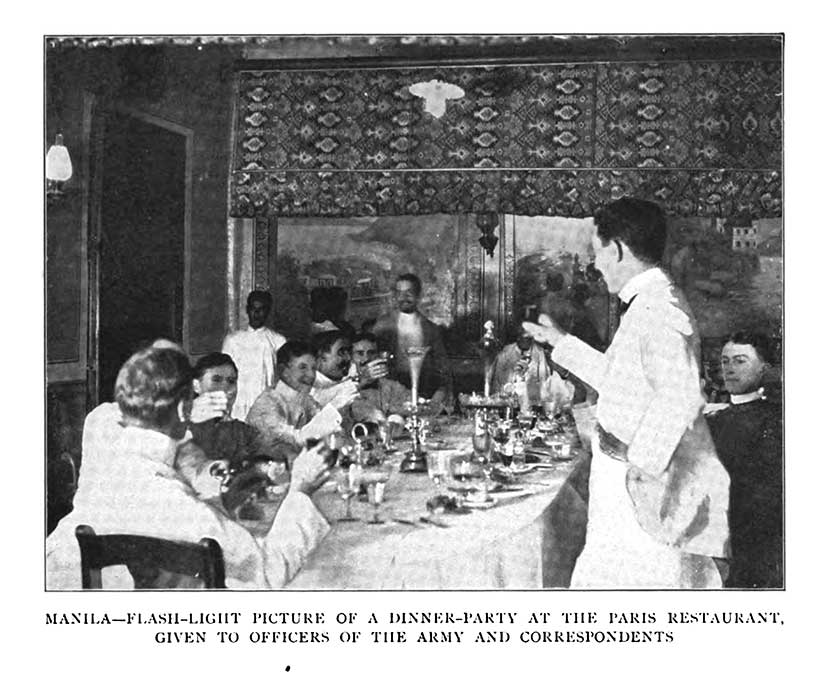

As you may remember from previous posts, the Americans turned this rich multilingual heritage into a justification for a monolingual (English) education system. English is still one of the two official languages of the country, along with Filipino. (Filipino is the “most prestigious variety” of the Tagalog language of Metro Manila, according to the chair of the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, or the Commission on the Filipino Language.)

For the purposes of my series, Filipino (or Tagalog) had not yet been designated official (1937), which means that regional languages, such as those in the Visayas (like Cebuano and Waray) would have been even stronger at the beginning of the twentieth century. I have to thank Liana Smith Bautista (and her mom) for being my newest go-to research sources on Cebuano, though all errors in my books are my own. I also am deeply indebted to the creator of the amazing Binisaya online dictionary and reference guide.

American readers, have I utterly confused you? The number of indigenous languages is daunting—and I have not even mentioned the foreign tongues spoken in some families, like Hokkien (from China). Is it any surprise that most Filipinos grow up bilingual, at the very least? As Javier said to Georgina when they first argued about her English textbooks: “I grew up bilingual, learned three more languages in school, and another while traveling. It’s only Americans who can’t seem to manage more than one.” (And with the direction of funding for foreign language education in US public schools, we will not be getting much better.)

Allegra is a polyglot, too, by the way:

“To be honest, it’s a little eerie how fluent you are. From what the folks here tell me, you also speak Spanish like an Iberian. And Cebuano, and Tagalog, and Latin . . .”

She used her free hand to wave away the compliment. “I grew up speaking Spanish in the house and Cebuano in town—and then Tagalog in Manila. No one but a priest speaks Latin, but I learned to read it in school—”

“You’re missing my point. You’re a linguist, a natural. If you study for the rest of this test with Allegra-like persistence—and maybe a little un-Allegra-like humility—I have no doubt you’ll pass next time.”

She blushed even more furiously than when he had first taken her hand. “Thank you.”

— Sugar Moon (upcoming)

Ben’s respect for Allegra’s intelligence has been one of the most fun things about writing this couple. He is not a scholar and doesn’t pretend to be, but he is not intimidated by her skills, either. In fact, as we’ll see, he needs them.

So we’ve gotten a little bit away from the bangka in this glossary “definition”—sorry—but you probably just needed a picture for that. (If you want more nautical know-how, read about this group trying to help local fishermen design bangkas out of fiberglass—a light, durable, super-typhoon-proof alternative to wood.) Otherwise, I hope that you, like me, have learned a larger lesson about language through the study of this one little word.

EDITED TO ADD: Bangka is also a verb! This is from Liana: “Also it’s to be noted that in Bisaya, bangka with a hard stress on the final syllable refers to a type of boat, but keep the pronunciation soft and it is a verb meaning to treat someone out (usually to a meal, but can be used in other contexts where you pay for another person’s fare, lodging, etc.). It’s not uncommon for my cousins to say ‘bangkahi ko, beh?’ (Won’t you treat me?) when we talk of going to lunch or seeing a movie, for example.”