In Under the Sugar Sun, Javier lamented his cousin Allegra’s wild side. At colegio the nuns claimed that she:

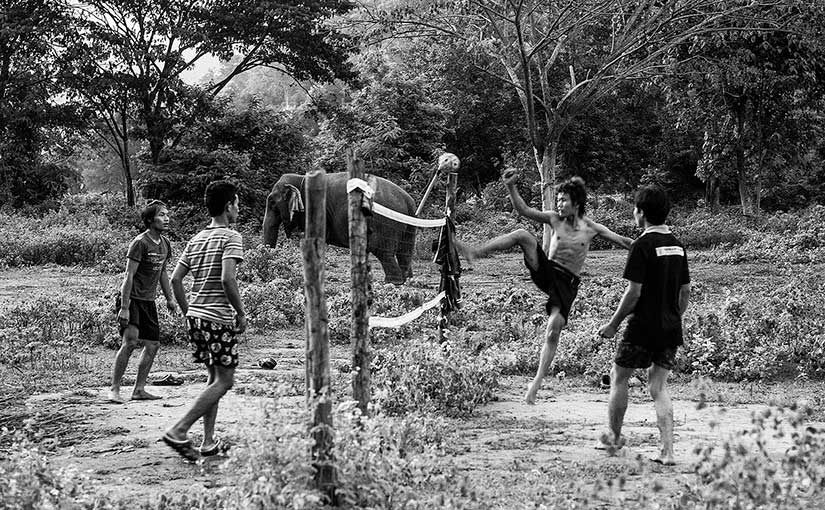

…refused to observe silence at meals, faked illnesses to get out of classes, and had a scandalous habit of bathing nude—thankfully, alone. What really gave the sisters apoplexy, though, were Allegra’s secret excursions to play sipa. No matter how many times they confiscated her shuttlecock, she could be found bouncing one off her bare heel the next day. When Javier declared that this was not a very ladylike pastime, she boasted that she could do over a hundred hits nonstop, and would he care to see?

In other words, while wearing a skirt, Allegra lifted her foot almost to hip height, exposing her thighs for several minutes at a time as she bounced an object on her foot in a Filipino version of hacky sack. (By the way, if you think Allegra will give up the pastime as she matures, you don’t have a real good grip on her character. And Javier will ultimately wish that sipa had been his greatest worry for his ward. In book two, Sugar Moon, she will fall for the very worst scoundrel possible—two, actually, though she’ll use one to make the other jealous. She does like mischief.)

In the case of sipa, though, Allegra is at least troublesome in a very patriotic way. “Sipa” or “kick” is a sport that predates the arrival of the Spanish. The earliest sources date to the 11th century in Southeast Asia and maybe all the way back to China’s legendary Emperor Huangdi in 2600 BCE!

There are several ancient Moro legends that revolve around sipa. For example, storm gods were said to kick around fireball sipas, and they kicked them so hard that they flew horizontally across the sky (i.e. lightning). Another legend says that the son of the sun and moon fell to earth while playing sipa, igniting a battle over parental supervision that ended in a prehistoric separation, which is why the sun and moon no longer share the sky. Yet another legend tells of a hero bouncing a rattan ball on his foot for two hours straight without fault in order to charm a widow out of her mourning.

When the Americans arrived in 1898, sport became a critical part of their “benevolent assimilation” plans. Yet, while the sanctimonious Yankees did try to eliminate cockfighting (unsuccessfully), they appreciated—or, at least, tolerated—sipa. True, one American called it “a very light form of sport” that was only “suited to an anemic people” and could not compete with “the more stirring games of modern basketball and baseball.” (See post #14 on racism.) However, another American described sipa as “a form of civilized football.” He explained that it “consists of really kicking the wicker ball, rather than the heads, ribs, etc., of fellow players in the game, as is customary in more boastful centers of civilization.”

One constabulary officer pointed out that since Moros used to have slaves to do ordinary work, they spent most of their latent energy on war or sipa. The officer was especially impressed at “the seeming ease with which a man’s foot appeared to reach behind and to the level of the opposite shoulder blade.” Sipa was even described in the souvenir brochure to the Philippine exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis World’s Fair) in 1904. The Americans allowed prisoners to play the game in penal colonies—along with basketball, volleyball, baseball, and other redeeming pursuits.

Since the earliest time of sipa in the Philippines, there were many regional variations, both in gameplay and in kicking object. There is the community game, where a circle of people keep the object in the air. Or there is the challenge type, where you try to make the most kicks in a row (Allegra’s choice). Or the distance game, where you try to kick it the farthest.

One could use a shuttlecock made of a washer with paper or feather, and this type of fly could be bounced off feet or elbows or hands, depending on preference.

A woven rattan ball was used consistently in the Moro lands, which makes sense given the cultural link these areas had with their Malay neighbors. This ball is what is used today in the energetic off-shoot of sipa called sepak takraw—a gymnastic blend of volleyball, badminton, and soccer. The net was added sometime around the turn of the 20th century, and each country has its own claim to put to the invention. (In the Philippines, it is Teodoro Valencia who supposedly created this sipa lambatan in the 1940s.)

Proof of how ingrained this sport was in 20th century Philippine culture, overseas workers took the game with them, even to Alaska. Filipinos working in salmon canneries in the 1930s described playing sipa until ten at night, as long as the daylight lasted.

However, by the 1990s sipa was on the wane. In 2009 President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo dethroned it as the national sport in favor of arnis, a martial art whose popularity has spread even to my small town in New Hampshire. (Known also as eskrima, this Filipino fighting technique will make an appearance in Sugar Moon, too.)

Some folks blame technology for taking kids off the playground and away from their traditional sports, a trend I see happening in the United States, as well. But, as with America, I wonder if our organized sports culture is really to blame. Kids do not run out and play pickup games anymore. They play on teams with coaches, referees, and uniforms. Sipa was actually removed from the elementary division of the Palarong Pambansa (National Games) in 2014. Now even the little ones play “sepak takraw junior,” a modified version of the regional net game. Maybe there is more future in that sport—one can travel and compete throughout ASEAN—but with all this competition, are we losing sight of fun?

Missing sipa? Don’t worry. There’s an app for that. The first Filipino-designed app on iTunes and Android was—yep, you guessed it—SIPA: Street Hacky Sack. There’s terrible irony here, I know, but the app looks beautiful. It takes the user through a tour of cultural Manila and encourages the player to pick up virtual litter along the way. (Genius, that.) In the “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” school of thought, the app is a winner. But I just can’t see Allegra playing it. Too tame.