How my grandmother ended up at a Cuban cockfight in a fur coat with a man who wasn’t her husband…

I was not born early enough to meet either Dominick or Carmela, my great-grandparents, and that is my loss. Both came to the United States as teenagers. Had they stayed in Italy, though, they might not have been allowed to marry. Carmela’s parents had been relatively well-off in Sicily, while Dominick had little formal education and was forced into the hard life of coal mining in the hills of West Virginia. Moving to the United States was a bit of an equalizer—all immigrants struggle—but Carmela’s family still had their pride. When Dominick proposed marriage, Carmela’s mother demanded that he build his bride a big house in Morgantown. None of their children could explain to me how he got the money to do that, but he did. And, in the day before interstate highways, he even managed to commute to and from the mine so that his wife did not have to live in the hollow.

Dominick worked hard and managed to keep his wife and seven children in their family home throughout the Great Depression. There are two reasons often given for how he accomplished this impressive feat. First, it seems that he was such a consistent and reliable worker that his boss at the mine always made sure to keep him on, despite dramatic layoffs. Second, and more relevant for these times, his mortgage was replaced by a loan from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a New Deal program. In this program, the federal government bought out mortgages from banks (who were happy to exchange it for bonds) and then gave a more favorable, more patient loan to the homeowner. Where was this in 2007, huh?

Not only did Dominick keep his job and his house, but he also made sure that his younger children—male and female—were college-educated at West Virginia University right down the street. Unfortunately, the older children were not so fortunate. For example, Dominick and Carmela’s eldest child, Josephine, was not able to go to college. This woman, my grandmother, graduated high school square in the middle of the Depression, in 1937. I still wear her class ring. (I guess the fact that she was still able to buy a class ring at this time is something, at least.)

Now, even though Dominick and Carmela married for love, they did not give Josephine the same choice. Her first marriage was arranged to another coal miner, and it failed—spectacularly. Her husband was domineering and abusive. This was my grandfather that I barely knew.

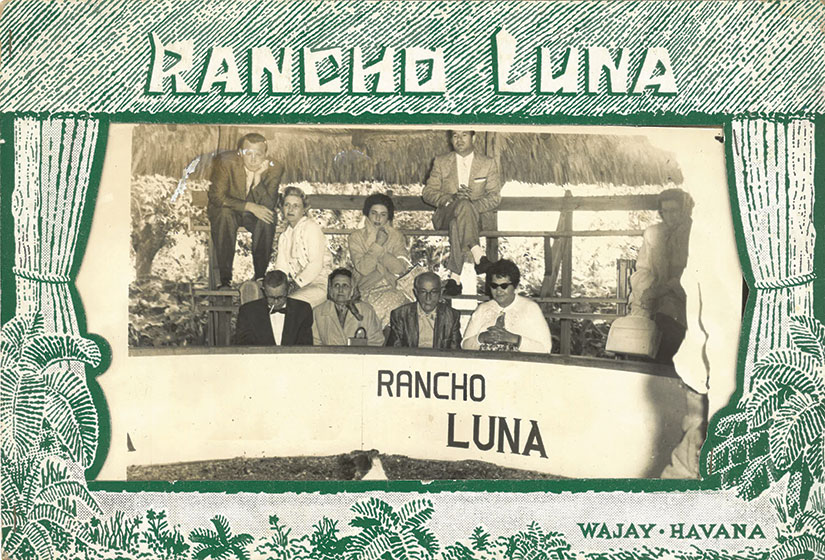

When my mother and her sister were in high school, Jo left her family for the man she had loved since high school. Why hadn’t she married Jess to begin with? Class mattered, once again. Jess’s family ran a profitable grocery store. While Dominick and Carmella were upstanding citizens and homeowners, their daughter was not what Jess’s family had in mind. After being denied this first time, Josephine and Jess ultimately ran away together. Far away. To Cuba. In 1958. The year before the revolution.

This is my favorite photo of Jo. This photo finds her and Jess watching a cockfight at a resort in Wajay, Havana. Apparently, it was cold because my grandmother is wearing a fur coat. Jess looks typically uptight next to her. They do not have the body language of recently requited lovers, to say the least. (Jess—or “Uncle Jess” as I called him—was never very demonstrative, to say the least, but he was always very kind to me.) They would later marry, divorce, and remarry. Status update: complicated.

The whole thing is still a sore subject in my family. It caused a lot of pain and embarrassment. It was the fifties, when Josephine’s Catholic family did not find domestic abuse a reason to dissolve a marriage. (They did not believe in divorce, in any case.) Moreover, because my grandmother was in Cuba, my mother and her sister had to change high schools and move in with their father, who quickly remarried to a recent widow with two daughters. (They lived in Fairmont, West Virginia, the birthplace of the pepperoni roll—see below—and the hometown of Della Berget, the heroine of Hotel Oriente.)

My mother’s relationship with Josephine thawed only when I grew to be about five or six years old. It was Josephine’s more settled and reliable sister, Anita, who planned my mother’s wedding, for example. It was Anita who still filled the role of grandmother for much of my life, until her death this past summer. (Miss you, Ya!)

Even after Josephine and Jess were invited back to the table, things did not always go smoothly. Jess became a landlord of student apartments in Morgantown, and it was Josephine’s job to scour them. Jo scrubbed floors during the day and sweated over the stove in the evening—hardly a romance. She worked hard, and my own mother resented Jess for that. Uncle Jess was certainly set in his ways by the time I knew him. He was a Pabst Blue Ribbon man—tall boys—and he wanted his beer with dinner. Not before dinner, not after dinner, but just as dinner hit the table. Yet he was Josephine’s choice. I cannot explain it.

I do have good memories of Josephine and Jess, though. They mostly involve obscene amounts of food. Thanksgiving included at least three main course choices—turkey, ham, and a meat chop of some kind—plus about a thousand side dishes, the best of which were the stuffed artichokes. Jess, the grocer’s son, never trusted any supermarket in Columbus, my hometown. Every holiday he arrived with a car of overflowing bags from his favorite Italian haunts in Morgantown. I appreciated his snobbery. We had a tradition that he would bring in the pepperoni bag first for me. It was a good tradition.

Josephine should get the most credit for the food, though. Another time, when my grandmother was staying with me while my parents were away, my high school boyfriend came over for dinner. She had prepared her signature dish: true Sicilian spaghetti with her own fresh pasta CUT BY HAND. He naively accepted her offer of seconds, which meant that she piled a new plate taller than the first. He looked at me, stunned, like he wanted me to get him out of eating the whole darned thing. I just shrugged at him. You don’t mess with an Italian grandma. Unfortunately, that kind of eating, along with chain-smoking, led to her unfortunate death in 1991. I miss her too.

As we approach Thanksgiving, I wanted to give thanks for the bounty we always enjoyed at Josephine’s table. Her legacy was complicated. Her (and her parents’) choices did not pay off, at least not for her. But she was not afraid to try, and I am thankful for that.