Once upon a time, Catholic-Protestant strife scorched Europe. In the seventeenth century, for example, about eight million people died in the Thirty Years War, almost a tenth of the estimated total population. Germany’s male population was cut by nearly half. There were also civil wars in France, England, Scotland, and Ireland, killing millions more. The Troubles in Northern Ireland in the late twentieth century were less deadly, but still deadly.

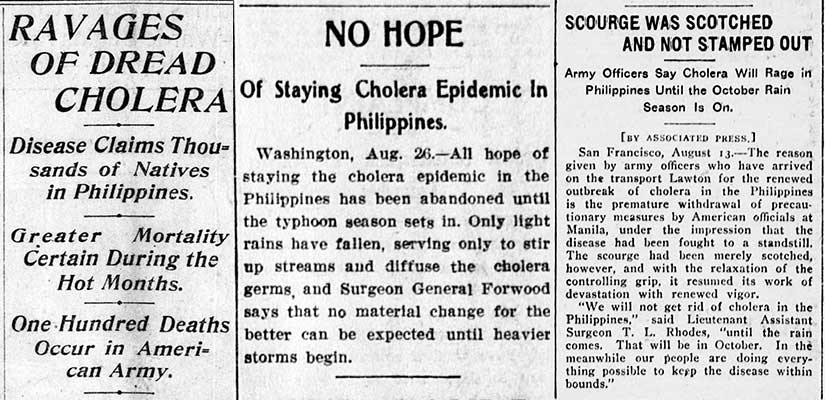

So intra-Christian conflict is not that unusual. Yet, far away in the Pacific, Spanish rule kept the competition away from Philippine shores. From northern Mindanao on up, there was no choice but Catholicism. When a hundred or so Yankee missionaries arrived on Philippine shores around 1900, though, things changed. There was no armed conflict, but the competition was still fierce. At least, the Protestants thought it was fierce. But over a hundred years later, only a small proportion of the Philippine population identify as Protestant—between two and ten percent, depending on whether you include independent nationalist movements with the American imports. Yet, despite this relatively small number, early American missionaries still had a significant impact on the face of Filipino society.

American Protestants did not want to see the return of the Spanish friars who had fled the country in the 1896 Philippine Revolution, and so they spread themselves out as widely as possible throughout the islands, taking up positions in vacated towns. They divided the large islands among themselves: the Presbyterians got Negros and Samar; Panay went to the Baptists; Mindanao went mostly to the Congregationalists; and Luzon was split between the Presbyterians, Methodists, and United Brethren. Only the Seventh Day Adventists and Episcopalians did not ratify this agreement.

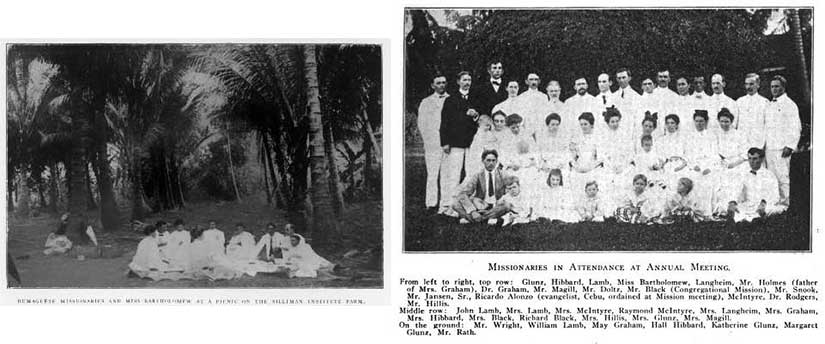

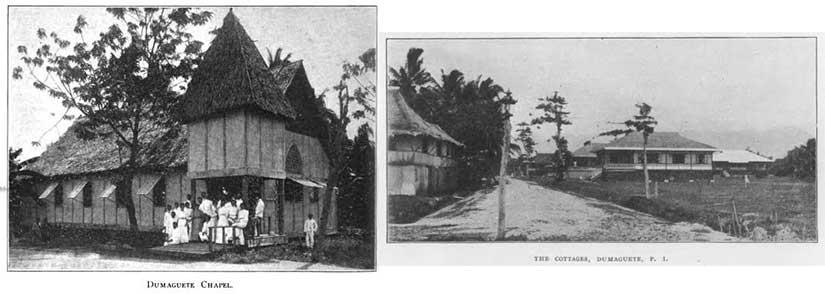

Silliman University in Dumaguete was begun by the Presbyterian missionary couple David and Laura Hibbard. In my Sugar Sun series, I’ve renamed the school Brinsmade and taken a lot of liberties with the characters, but it’s not all fiction. A lot of the general priggishness that comes out of the mouth of my character Daniel Stinnett, president of Brinsmade, is stuff American missionaries really said or wrote down. In my new novella, Tempting Hymn, you get a very intimate look at what these communities might have been like. My hero, Jonas, is a good man whose ecumenical faith will be challenged by some of the more small-minded missionaries with whom he works. It was important to me that Rosa and Jonas find common ground in a world complicated by church politics and colonial attitudes. I sometimes get to write what I wished had happened in history.

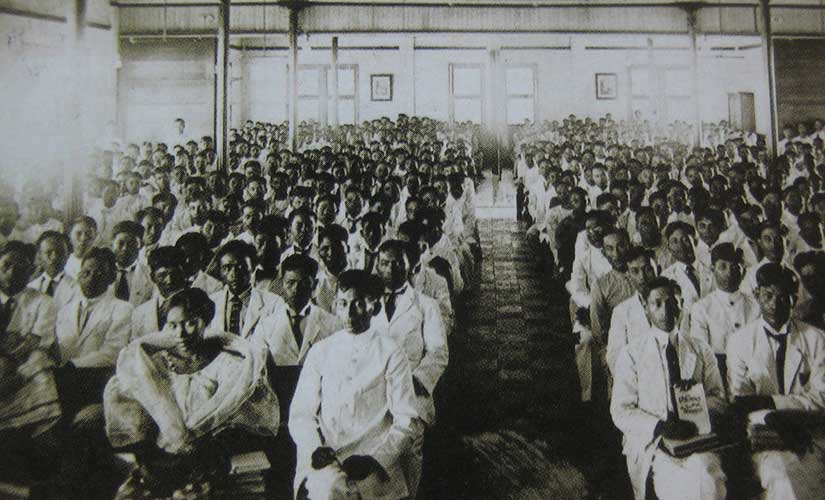

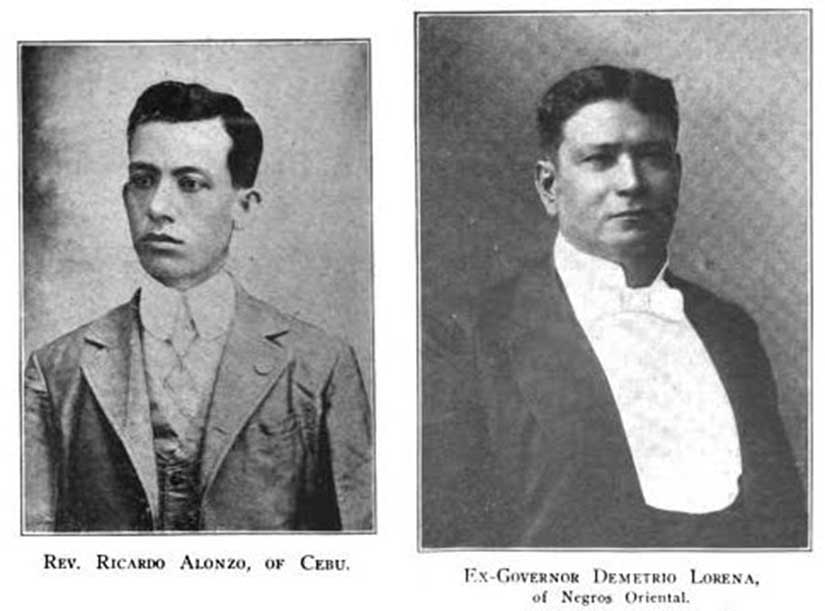

And, it is true, the missionaries did do some good work. First, they could be more inclusive than normal colonial officials. They offered opportunities for Filipinos to join their ranks as members, ministers, and missionaries. At Silliman, a Filipino had to pass an examination and earn the members’ vote, but if he or she (most likely he) did so, he could be tasked to spread the word throughout the rest of Negros and Cebu islands. By 1907, only six years after the founding of Silliman, there were five ordained Filipino ministers. They could preach in their vernacular languages—in fact, it was encouraged in order to reach a wider audience.

The other key advantage of the missionaries’ presence were the services they provided, particularly in education and health. Silliman was a school, after all. The American missionaries understood that the Thomasites, the American public school teachers, were doing good work, but they still thought that a secular curriculum was incomplete. David Hibbard integrated religion into the regular coursework and included several prayer sessions a week, including three commitments on Sunday. But Silliman’s reading, writing, and arithmetic education did not suffer because of it. In fact, his students had good success in finding employment in the new colonial government:

One boy, Andres Pada, who came to us a raw unlikely specimen three years ago has been appointed an Inspector of the Secondary Public School building and is giving good satisfaction. Another boy named Apolonario Bagay has been appointed as overseer of the roads for a portion of the province and is doing good work there. Four or five of the boys have gone out this year as teachers in the public schools of the province, and though they have not had enough training to do very good work yet, I have heard no complaints.

Okay, that seems like being damned with faint praise, but it was quite complimentary by American missionary standards. And Silliman was so popular in the region that they had more applicants than they could handle. They had to turn away boarders and take only “externos,” or day students. The local elites embraced the Hibbards and Silliman in general. In 1907, Demetrio Larena, the former governor of Negros Oriental province (and brother to the mayor of Dumaguete), converted to Presbyterianism. Silliman is now one of the best private universities in the Philippines, and it might have grown strong partly because of the very favorable town-gown relations, right from the start.

American missionaries did more than educate, though. They also brought medical personnel to Asia. Interestingly, several of these doctors were women. In the Presbyterians’ list of new missionaries in June 1907, there were three single female doctors—two were sent to China and one to the Philippines. Another woman physician, Dr. Mary Hannah Fulton, started a medical college for women in China. One female doctor, Rebecca Parrish, will be the model for a future character of mine, Liddy Shepherd, heroine of Sugar Communion.

The real Dr. Parrish founded the Mary Johnston Hospital and School of Nursing in an impoverished area north of Manila, and she would give 27 years of service there before retiring. In 1950 Philippine president Elpidio Quirino bestowed upon her a medal of honor for her work. I’ve taken some liberties (as I do), but her passion for providing a safe place for women to give birth will translate to a similar compassion in my heroine, Liddy. And both were trained in the (new!) scientific medicine of the day.

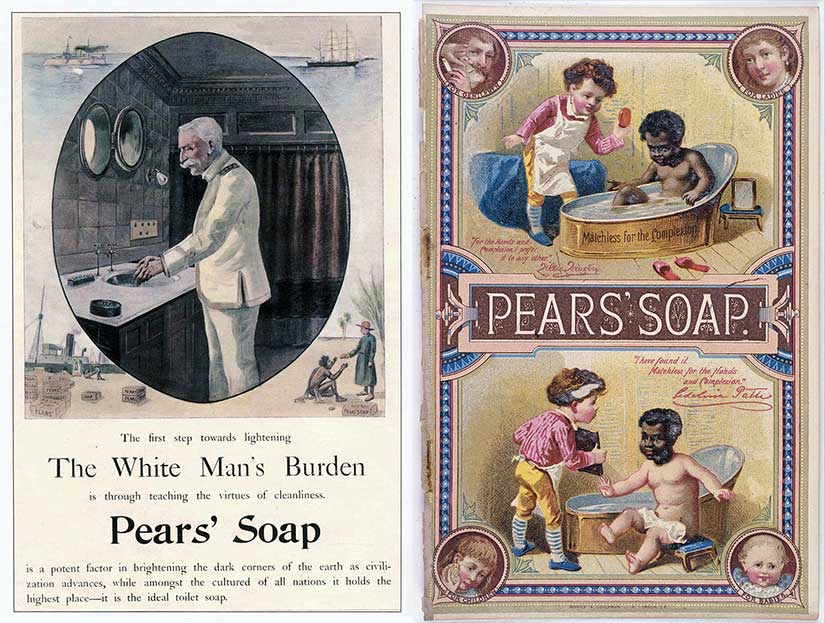

Of course, you might wonder why Christians would want to spread their faith to other Christians—until you realize that, at the turn of the century, many American Protestants did not think Catholics were Christians. They put “papists,” as they called them, right alongside infidels, idolators, and heretics. Reverend Roy H. Brown said:

Three hundred years have passed since this people first heard the Gospel from the Catholic Priests, and yet their condition morally is appalling….Saints and Mary are revered and worshiped while Christ is forgotten, and His place usurped….They know nothing about Christ or the Bible; their religion is a mixture of paganism with Christianity with the religious nomenclature.

This bias included a proscription against marriage to Catholics. In the Presbyterian version of the Westminster Confession of Faith at the end of the nineteenth century, it said that those who “profess the true reformed religion should not marry with infidels, Papists, or other idolaters, neither should such as are godly be unequally yoked by marrying with such as are notoriously wicked in their life or maintain damnable heresies.” Since they did not consider marriage a sacrament, you did not have to marry in a church—but the church was still going to tell you whom to marry. I fudged the rules a bit in Tempting Hymn when I allowed Jonas to marry Rosa, a Catholic, though his Presbyterian friends are none too happy about it. (And, you may remember that in Under the Sugar Sun, Georgina and Ben’s parents’ Catholic-Protestant marriage had been a scandal back in Boston.)

There were some more progressive missionaries, of course. In fact, the first Presbyterian missionary to arrive in the Philippines, Rev. Dr. James D. Rodgers, said that the purpose of the mission was “to help Christians of all classes to become better Christians.”

Still, in the end, the Protestants had more in common with each other than with the Catholics. And since the enemy of my enemy is my friend, the American denominations—the Presbyterians, Disciples of Christ, Evangelical United Brethren, Philippine Methodists, and the Congregational Church—would decide to merge into the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP). It was their hope that this would provide more unity to fight the Catholic front.

It was not very successful. These more traditional churches would end up losing the war to the nationalized independent churches (like Iglesia ni Cristo), along with the Seventh Day Adventists and more recent missionaries like the Jehovah’s Witnesses. But, in the end, numbers may not matter. The real impact these missionaries would have would be social and academic, not spiritual.

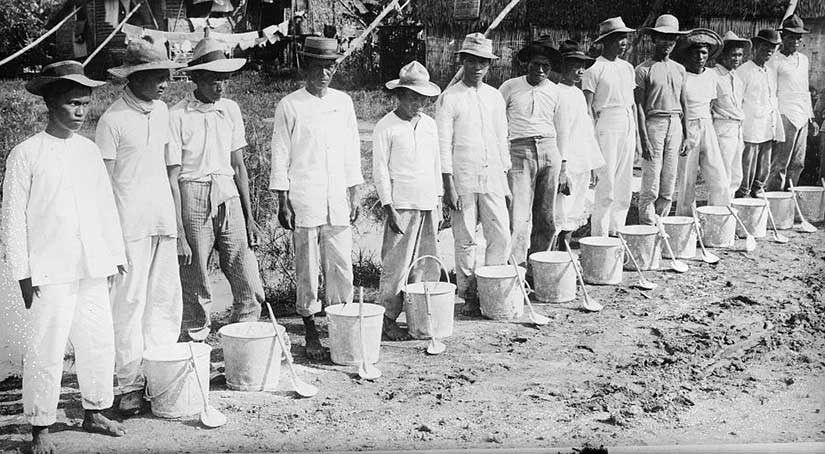

Featured image of an old Dumaguete postcard.