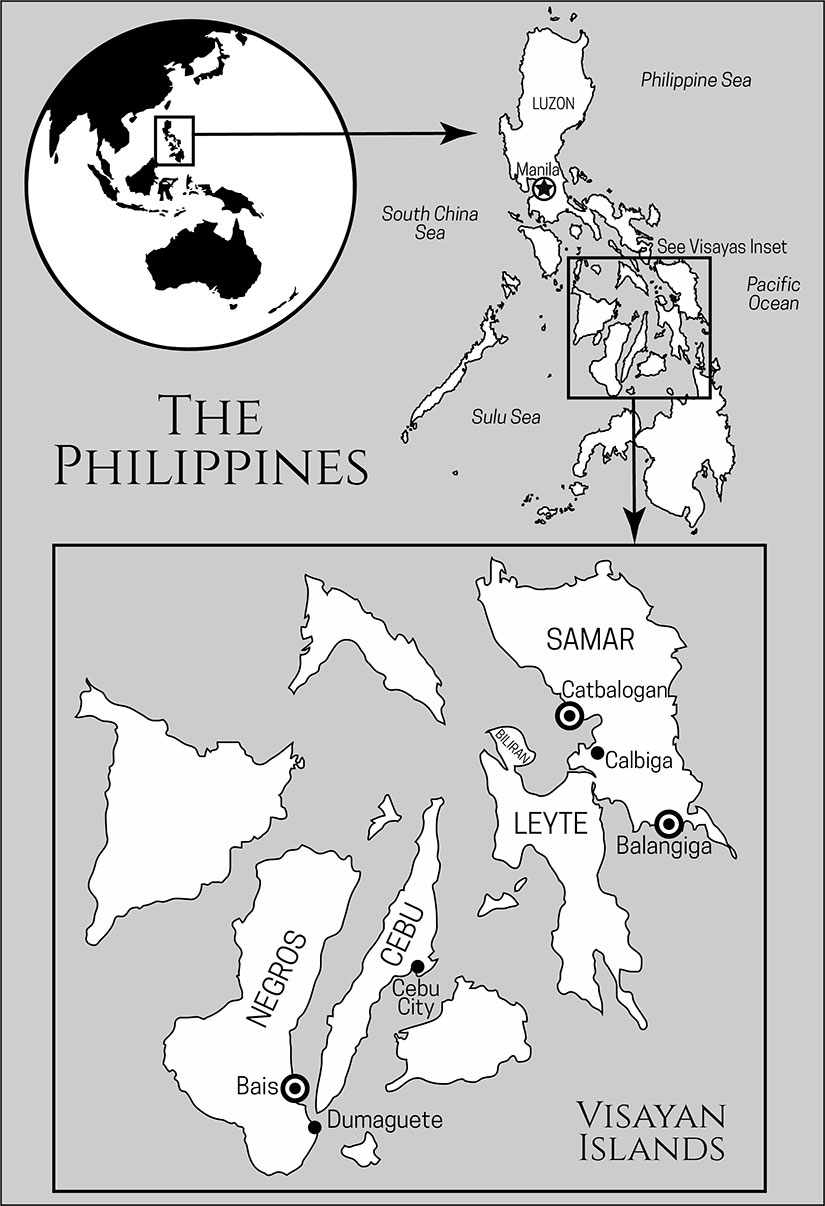

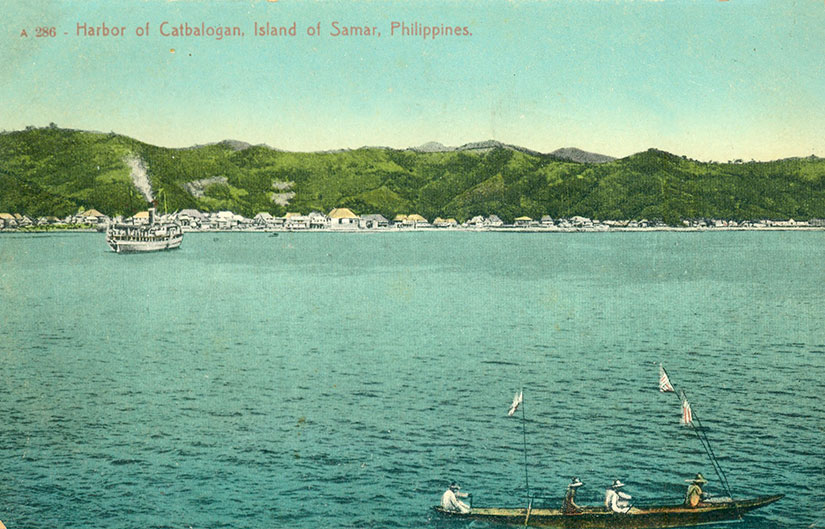

Catbalogan means “an everlasting place of safety,” and for hundreds of years it was safe—for pirates. The sheltered bayside harbor lies just north of the San Juanico Strait between Samar and Leyte, a key access point to the Pacific Ocean and the primary shipping route for the Spanish galleons. Since these vessels were headed to Manila with silver and then back to Acapulco with a hold full of porcelain and spices, they were ripe targets for pirates, right? And by “pirates” I mean the English and the Dutch privateers, who were licensed by their sovereigns to interdict and steal the Spanish bounty. Catbalogan became a haven for pirates and privateers, their crews, and lost sailors.

The Americans would find the city no easier to manage in the early twentieth century. For the first year of the Philippine-American War, the Yanks mostly ignored Samar because they had their hands full in Luzon. But then, in January 1900, gunships arrived offshore Catbalogan and sent a messenger to General Vicente Lukban, the Philippine revolutionary in charge of Samar and Leyte. The Americans wanted to negotiate a surrender of the whole island by offering Lukban the governorship of Samar. But Lukban wanted more than a title; he wanted full local autonomy. The Americans refused, so Lukban forbade them from landing. In turn, the Americans began to bombard the town. In other words, things escalated fast. Unable to withstand the US Navy’s firepower, Lukban and many of the locals abandoned Catbalogan, burning it as they retreated.

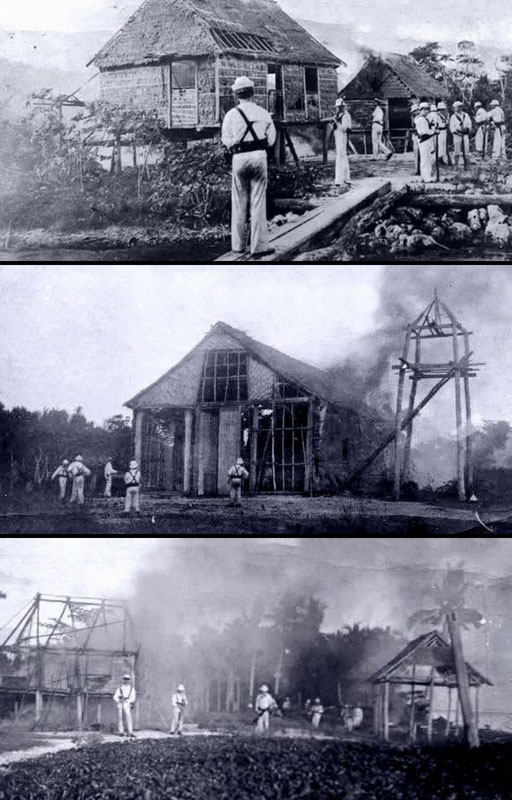

What followed was a ruthless two-year war to subdue the revolutionary forces in Samar. Company C of the Ninth Infantry was stationed to Balangiga to prevent Lukban’s men from using the southern port to import arms and supplies. On its own accord, the town ambushed the garrison in September 1901, and the American military took revenge on all of Samar. General Jacob Smith (known in the press as “Hell-Roaring Jake”) vowed to make the island a “howling wilderness.” Dusting off a legal gem from the American Civil War known as General Order 100, the Americans aimed to starve, burn out, torture, and kill as many guerrillas as possible. They even took the bells of Balangiga church. Catbalogan and Tacloban (Leyte) were the centers of American authority in this period.

General Smith’s “short, severe war” was both. The death toll from this period ranges from two to fifteen thousand. The extremity of Smith’s orders—to kill all those capable of bearing arms, which he defined as over ten years old—would lead to his court-martial and removal. (Yes, I know this seems like a slap on the wrist, and it was. But President Roosevelt actually forced his retirement against army and public opinion, according to this New York Times article. In an interesting side note, this was Smith’s first court-martial: “Hell-roaring Jake” was a petty crook, as well as a blow-hard war criminal.)

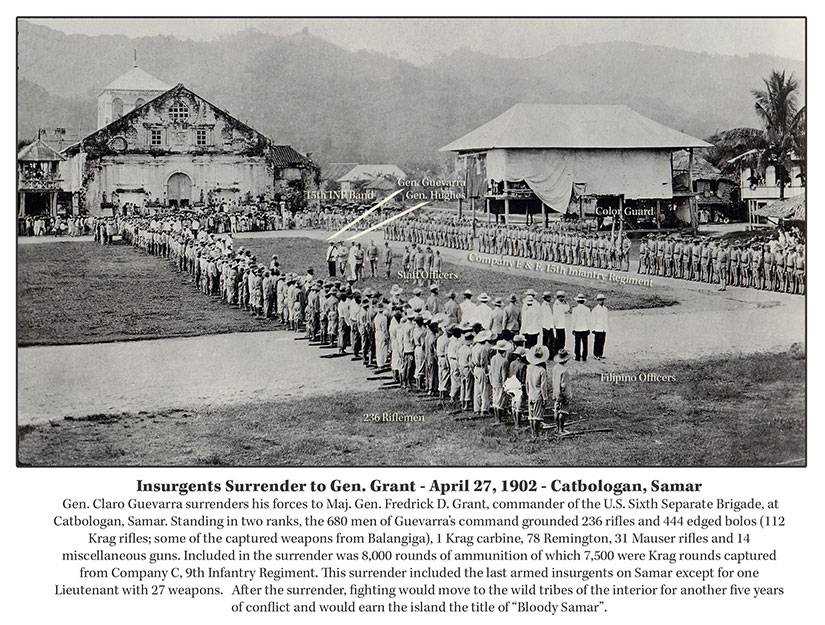

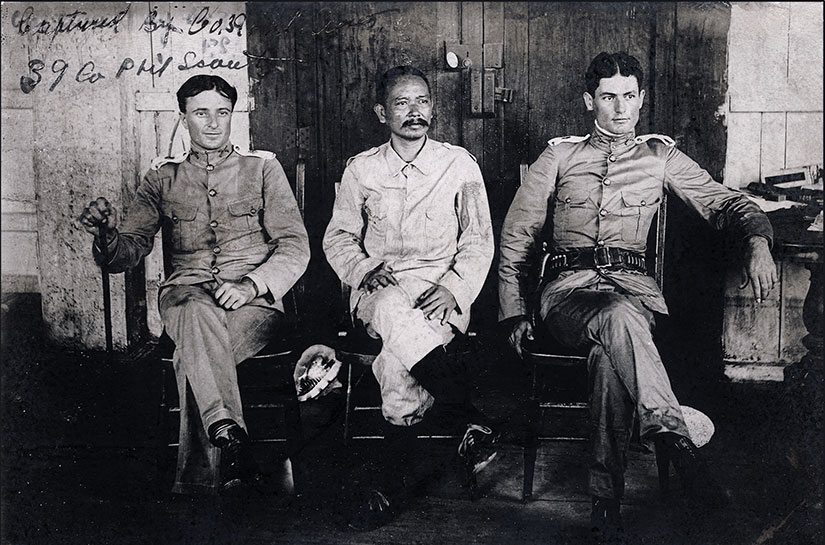

Still, contemporary American generals argued that a strong hand in Samar was necessary. They argued this strong hand was exactly the reason that Lukban’s forces surrendered in April 1902 in a grand ceremony in Catbalogan. (Lukban himself had already been captured.)

Those surrendering had to turn over their rifles captured from Balangiga the previous year and pledge loyalty to the United States, but then they were freed. Lukban himself would become mayor of the Tabayas province (now Quezon) within ten years. This begs the question of whether it was the severity of the fight or the quality of the peace that pacified the countryside? Amnesty is not used much in America’s modern war playbook, and I wonder if this is an oversight.

There is an interesting fashion note worth mentioning: the Americans did loan the revolutionaries a few Singer sewing machines so they could surrender in style with new (and complete) uniforms. Pride was salvaged all around.

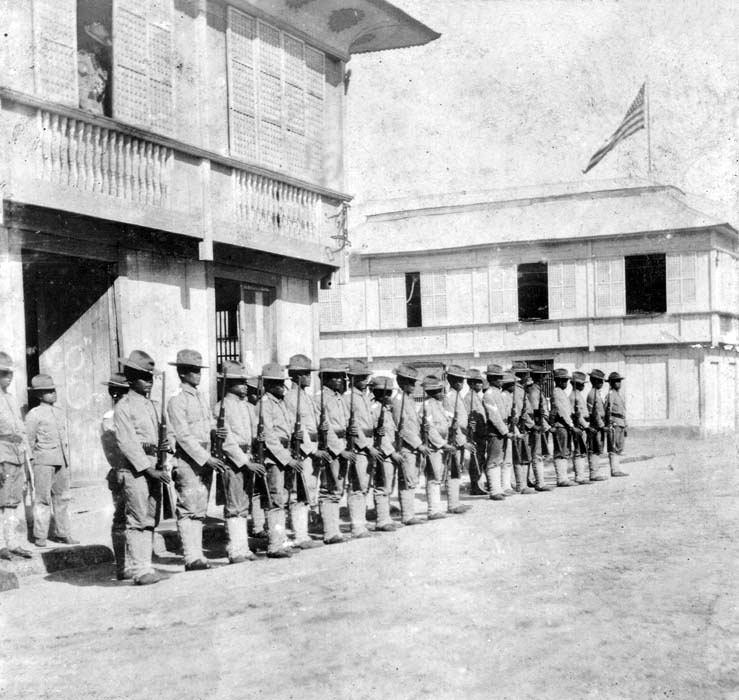

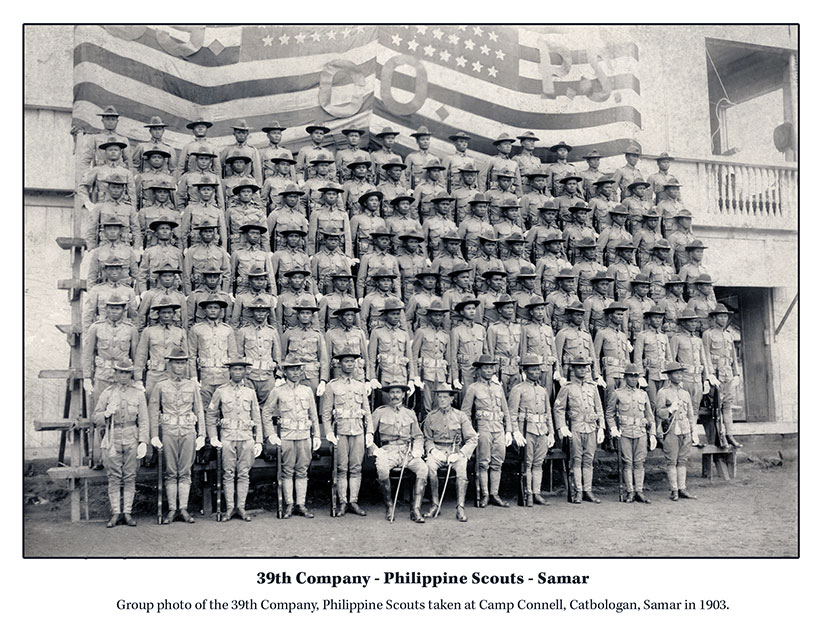

This is not the end of the story, though. This first war—including the destruction of half the municipalities in Samar and the burning of tens of thousands of tons of rice—caused a lingering famine and sparked another war two years later. Today, we call this phenomenon “blowback.” The Pulahan War was both a civil war (inland highlanders against lowland merchants and farmers) and an anti-American insurrection. On the American side, it was fought by the Philippine Constabulary, Third District—a civil police force organized, funded, equipped (not well), and trained by Americans (usually former soldiers). And by the 39th Philippine Scouts, trained and equipped (with better rifles) by the US Army. Both these units had significant troop presences in Catbalogan, along with the 6th, 12th, and 21st U.S. Infantries.

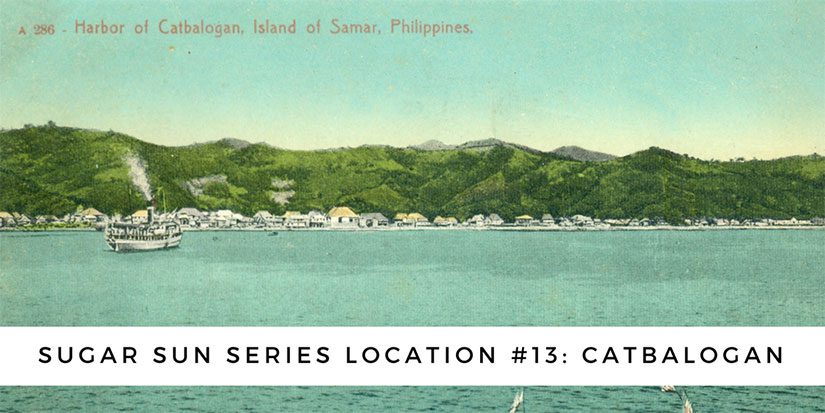

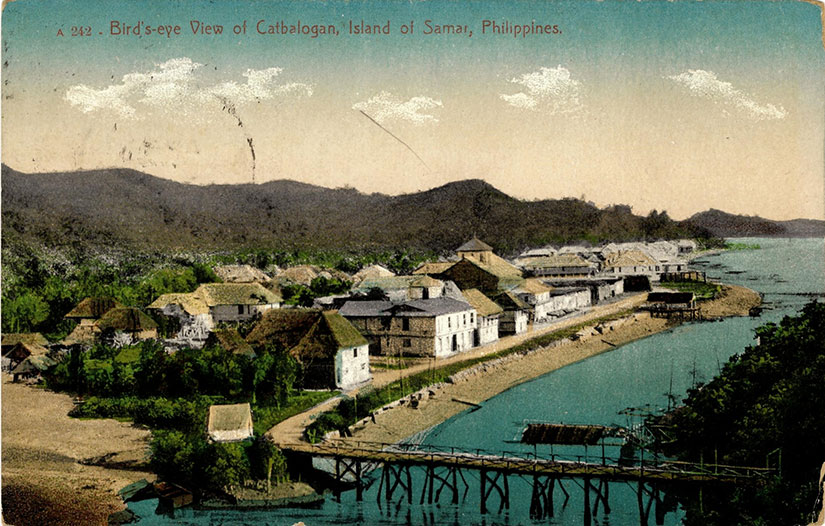

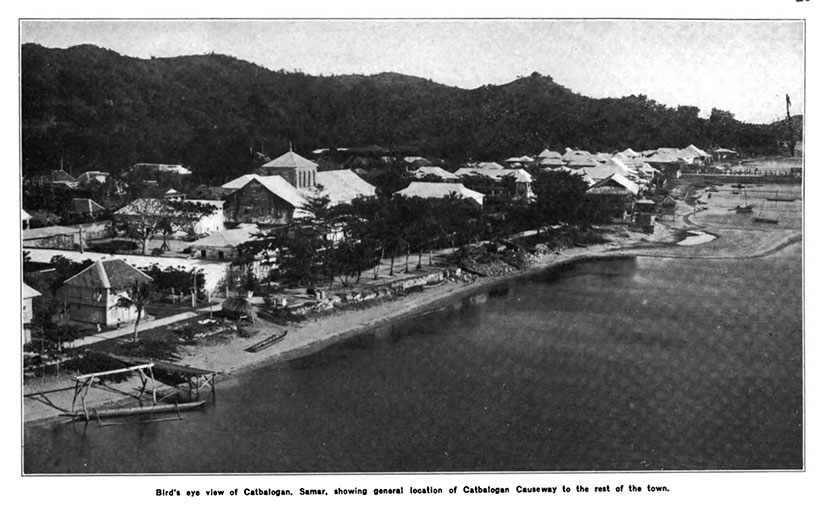

Catbalogan was a highly fortified town, but it was still beautiful. The ring of mountains separating it from the suffering of the rest of Samar did make for a stunning backdrop.

The city fared better than the rest of Samar through the lean times. Though the galleons no longer journeyed back and forth to Spain, Catbalogan was a center of the abaca trade in the 19th and 20th centuries, hence the large buildings and church. Abaca, also called Manila hemp, was in high demand as naval cordage. Its trade was dominated by ethnic Chinese and British merchants, and once Samar was no longer in ashes, the fiber would revive and bring an influx of capital to Catbalogan.

In the early twentieth century, Americans complained about the lack of poultry, eggs, and fruit in Catbalogan. (I find the fruit claim hard to believe.) They also complained about the lack of dedicated school buildings—not one in the whole town—and the lack of teachers. (Whose fault is that?) And they complained that there were only five miles of road on the whole island. The Americans would build more.

I traveled to Samar in 2005—and while I would not recommend December for your trip because of the rain, I loved it. The island is just as breathtaking as the postcards from 100 years ago.

Another view of the coast and causeway from the Quarterly Bulletin of the Bureau of Public Works.