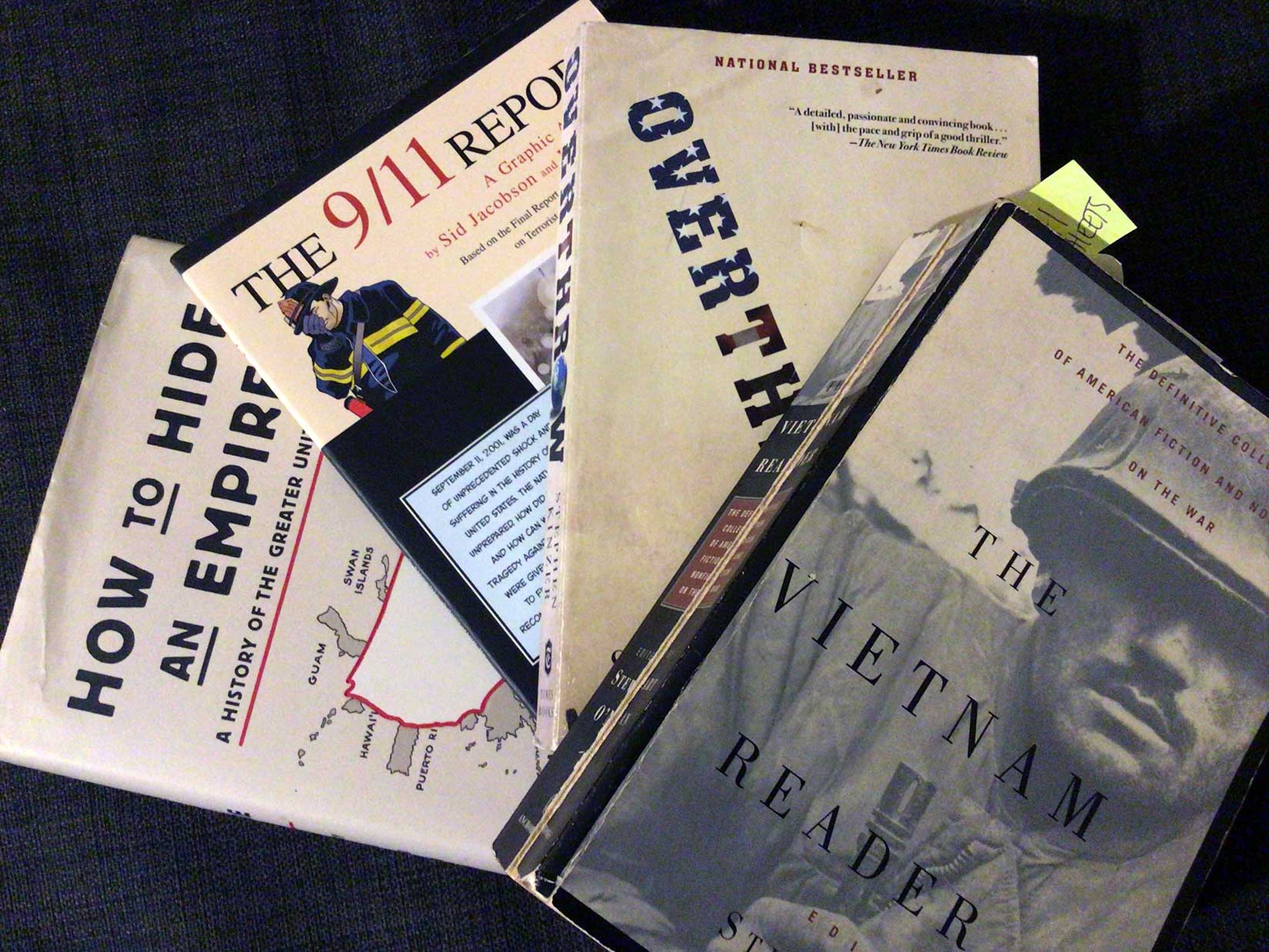

A year ago, I posted a list of non-fiction recommendations from my high school courses on American imperialism.

It’s taken me a year to put something together on fiction, and the brief has shifted a bit in the process because I stumbled onto three different Philippine-set audiobooks narrated by the same Filipino American voice artist, Ramón de Ocampo. My de-Ocampo-fan-girling was not intentional, but he narrates so many books published in the US by Filipino and Filipino diaspora authors that it was unavoidable. I wish UK and US publishers built a larger stable of voice actors from the Philippines itself, but Ocampo is fantastic. He is particularly good at giving characters unique inflections, pacing, and tone. You hardly need dialogue tags because the different speakers are so clear.

Despite these three books being voiced by the same person, each story is unique. You do not need to listen to the audiobook version to appreciate the novels, but de Ocampo does add value. I listened to all the audiobooks for free, either courtesy of my local library on the LibbyApp (Bone Talk, Patron Saints of Nothing, and Smaller and Smaller Circles) or a free trial from Scribd (Bone Talk and Smaller and Smaller Circles only). All three are on Audible too (Bone Talk, Patron Saints of Nothing, and Smaller and Smaller Circles).

This post, part one, will only discuss only the first book, Bone Talk, because I have a lot to say about this deceptively complex and widely underrated “children’s book” on the Philippine-American War. Part Two will discuss Patron Saints of Nothing and Smaller and Smaller Circles, both of which have more contemporary settings.

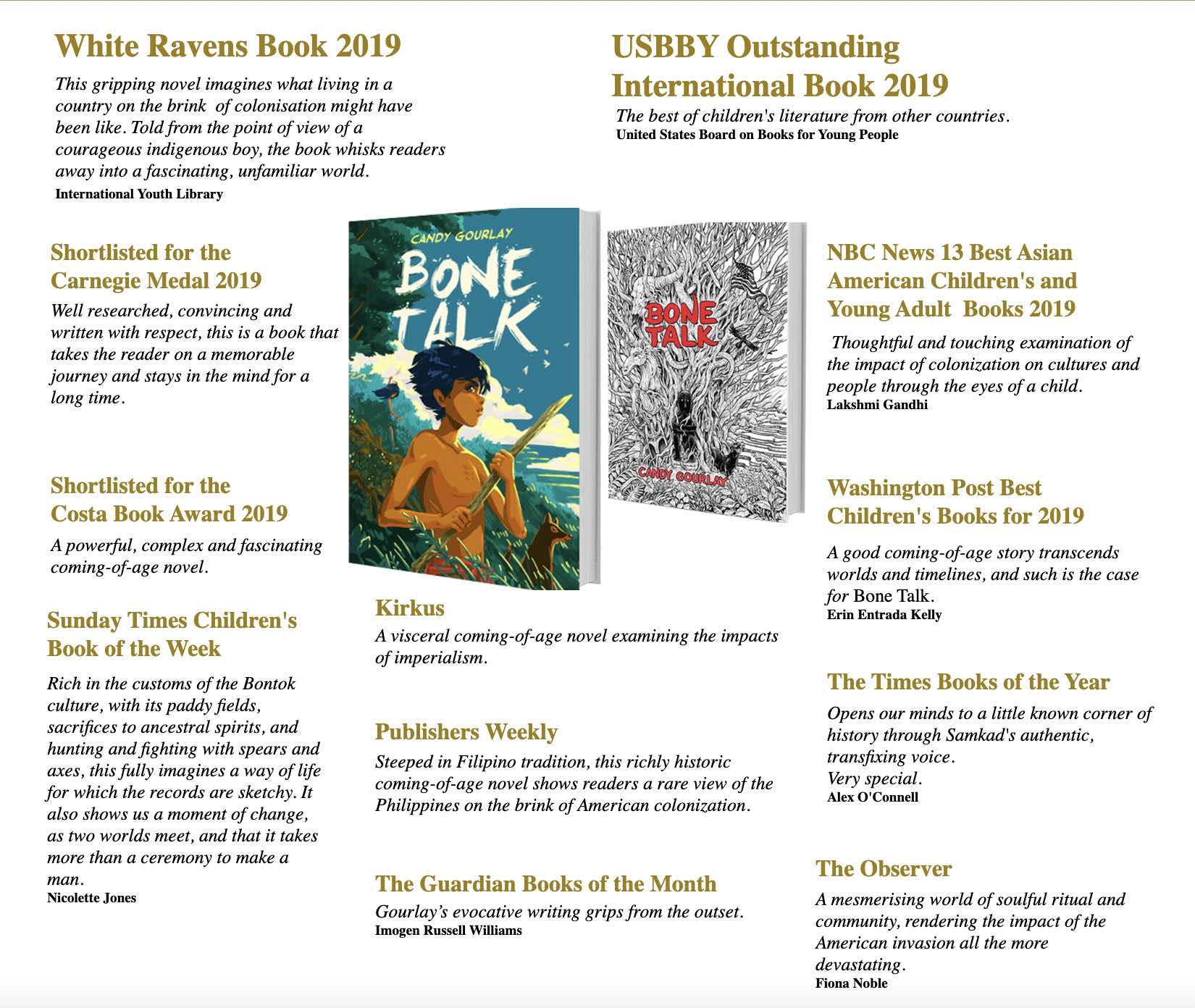

Bone talk by candy gourlay

Blurb by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center’s Book Dragon: “A Filipino boy on the verge of manhood in 1899 must face mortal enemies, colonial brutality, and his own headstrong, immature self to help save his remote village from annihilation.”

Bone Talk is a sophisticated book that brings little-known history and marginalized cultures to the fore. Sophisticated, but isn’t it juvenile fiction? Award-winning juvenile fiction, you say, but still a children’s book? Yes, the publisher markets Bone Talk for grade 6 to 9, but it is really for everyone. (And in the Philippines, they know it. Here too.) As with To Kill a Mockingbird or Huckleberry Finn, there’s no reason that a nine-year-old or thirteen-year-old protagonist should limit a book’s theme. Better than TKAM and Huck Finn, though, Bone Talk does not view the Cordillera people of 1899 through a white gaze. Instead, our guide is Samkad, a Bontok boy. (Bone Talk is a play on words: about the Bontoc municipality and the Bontok people.)

Samkad’s voice gives the story a directness and vision that matches author Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. As literary scholar Emmanuel Obiechina wrote about the Nigerian novel: “There is no loitering along the wayside for little irrelevant chit-chat, no pseudo-philosophizing, no awkward asides, no finger-pointing and no instant homilies which, though interesting in themselves, succeed only in detaining the reader and slowing down the tempo of the narrative.” The same is true for Bone Talk. I do not think a book written for ten-year-old boys can survive with “irrelevant chit-chat” or “instant homilies.” Boring books will not be read by children with smart phones and Netflix.

Like Things Fall Apart, a significant part of Bone Talk begins without any outside involvement. The village stands on its own. Expectations, ethics, and behavior are traditional and autonomous.

The reader is absorbed into this world through Samkad’s personal journey. More than anything he wants to be like his father and the other village warriors. He anticipates the day that the elders (“the ancients”) will deem him ready for the rite of passage required to become a man: the Cut (circumcision, tuli in Filipino). What does it even mean to “be a man”? Does Samkad understand those expectations, or does he just crave status? Remember, he’s ten, so he’s not the most reliable of narrators. And what are the expectations of dress and duty for women? Luki, his best friend, she wants to be a warrior too—partly because she is quite brave, and partly because she knows that adulthood will create a gendered rift in their childhood friendship. The ending of the book nudges tradition forward a little, and yet it feels authentic, which I think was Gourlay’s intention. There is a lot to unpack here for a modern audience—or a family reading the book together, maybe?

It is worth pointing out that Philippine-born Gourlay is not from the Cordillera Mountains herself. (Originally from Davao City, Ateneo de Manila graduate Gourlay was a journalist and associate editor of the weekly 1980s opposition tabloid Mr & Ms Special Edition, according to Wikipedia.) As a “lowlander,” Gourlay would be almost as much of an outsider as the Spanish and Americans. She admits her limitations: “I do not hail from the Cordillera and I beg the forgiveness of its many and diverse peoples for any misreadings of their culture. As a storyteller I can only spin a pale imitation of any reality.” She certainly did her research, including extended visits in Maligcong and conversations with members of the community, as detailed in her acknowledgments.

As Gourlay wrote, this is a book about first contact, with the additional complexity of Samkad’s soul being tied to a young orphaned Bontok boy who was raised down the mountains among Tagalog-speakers. There are concentric circles of identity at play here, and that is a very appropriate conversation for adults and children alike today. In the end, what best defines identity: birth, upbringing, or beliefs? Maybe all of the above.

Adding to the layers of identity are layers of enemies, including a fictionalized Cordillera people, the Mangili. As in Chinua Achebe’s novel, the distraction of outsiders weakens a society, making it more vulnerable to attacks by insiders.

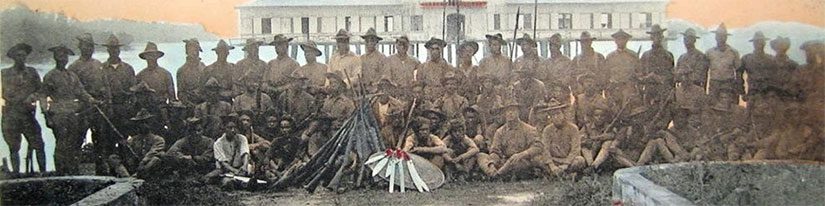

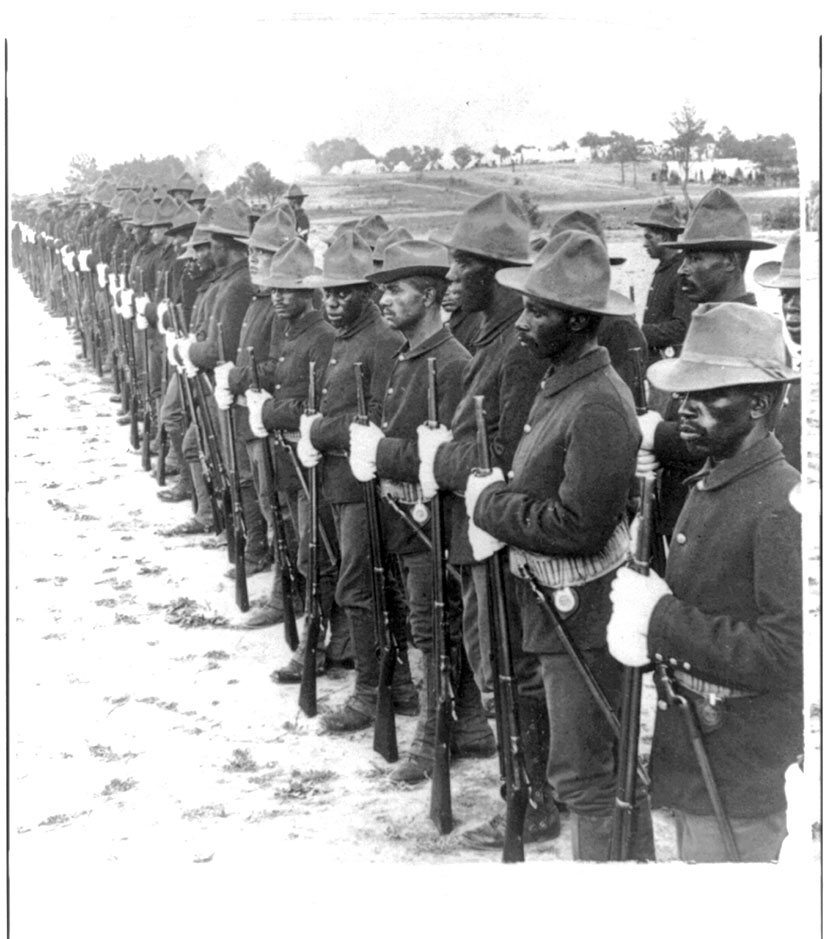

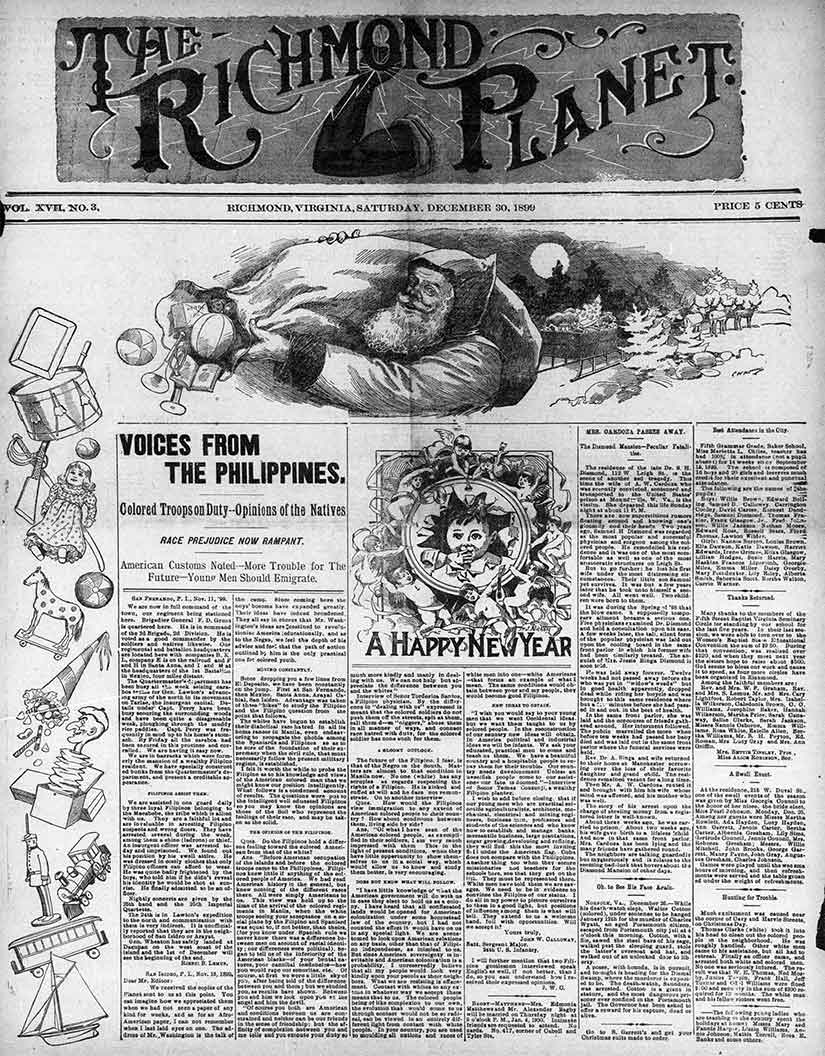

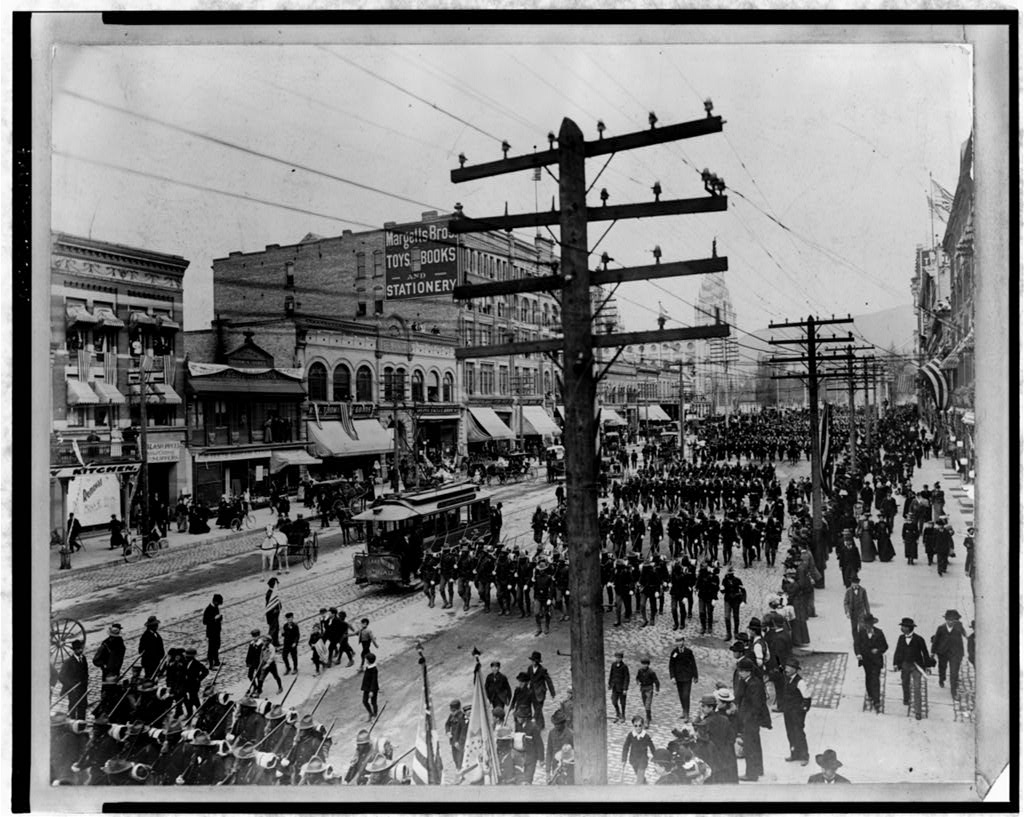

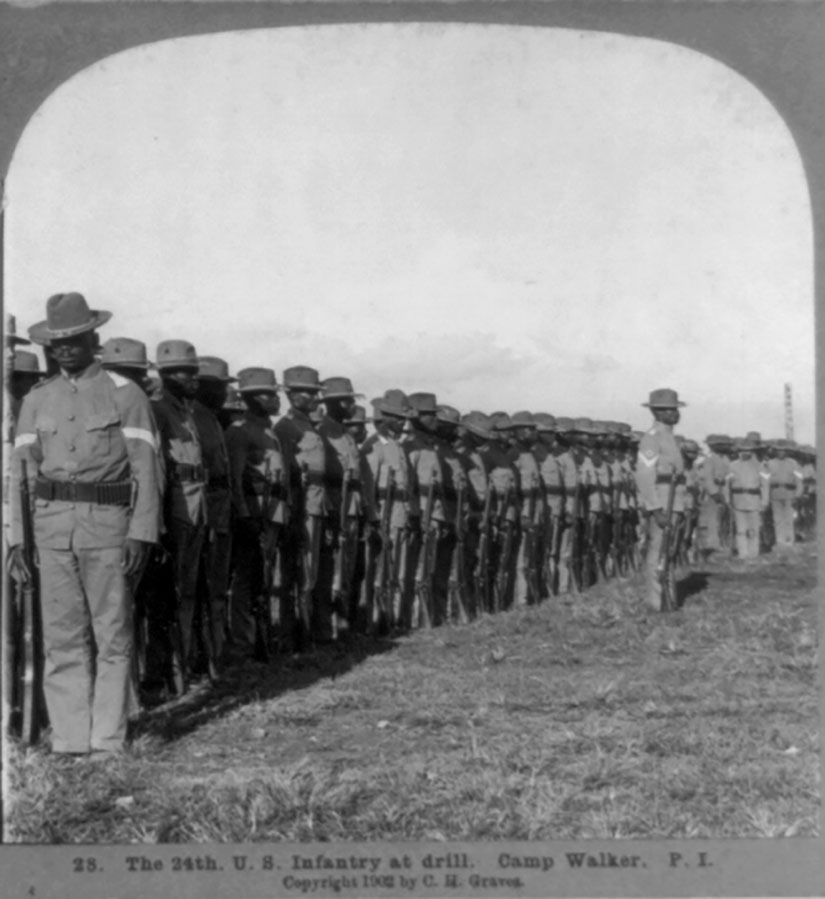

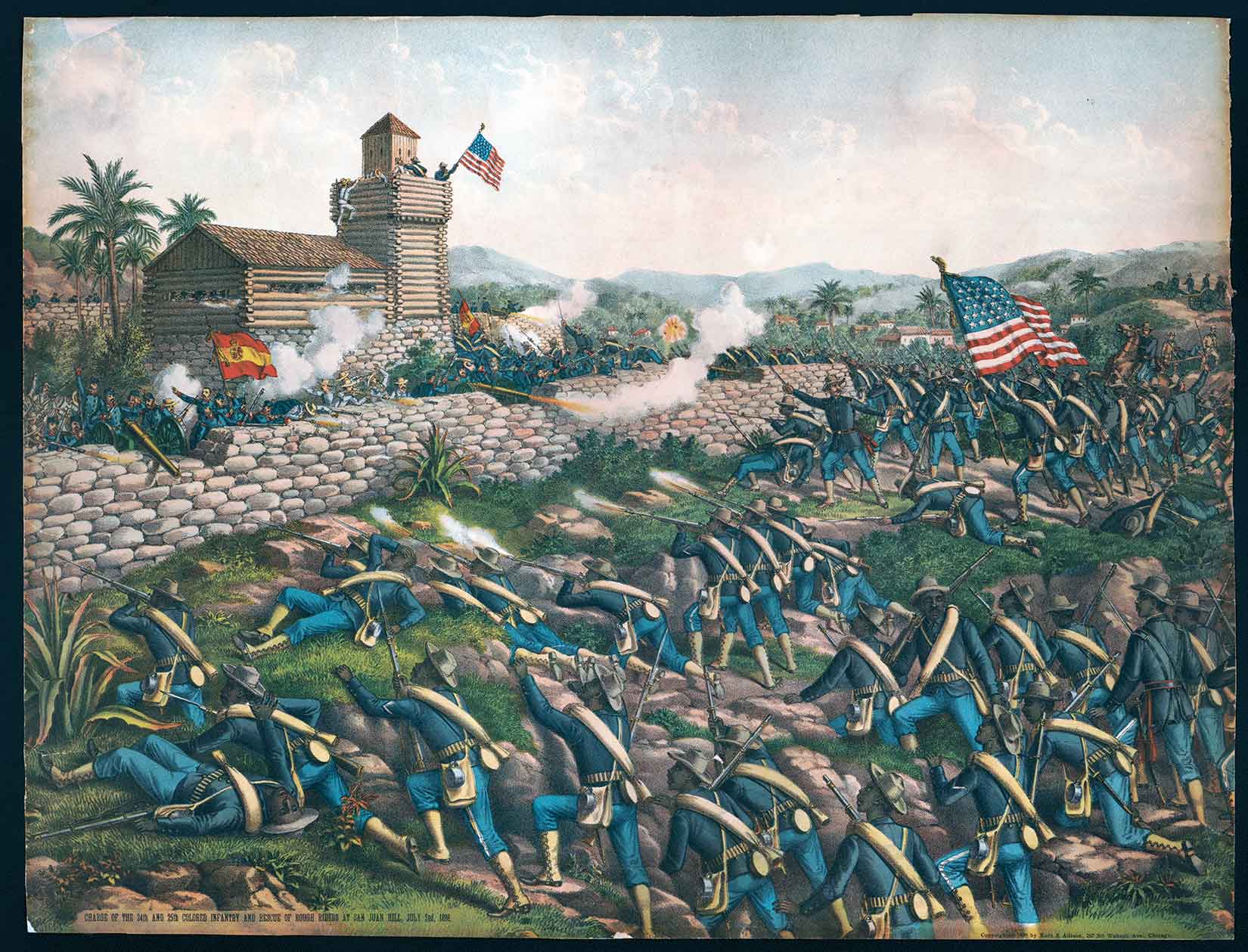

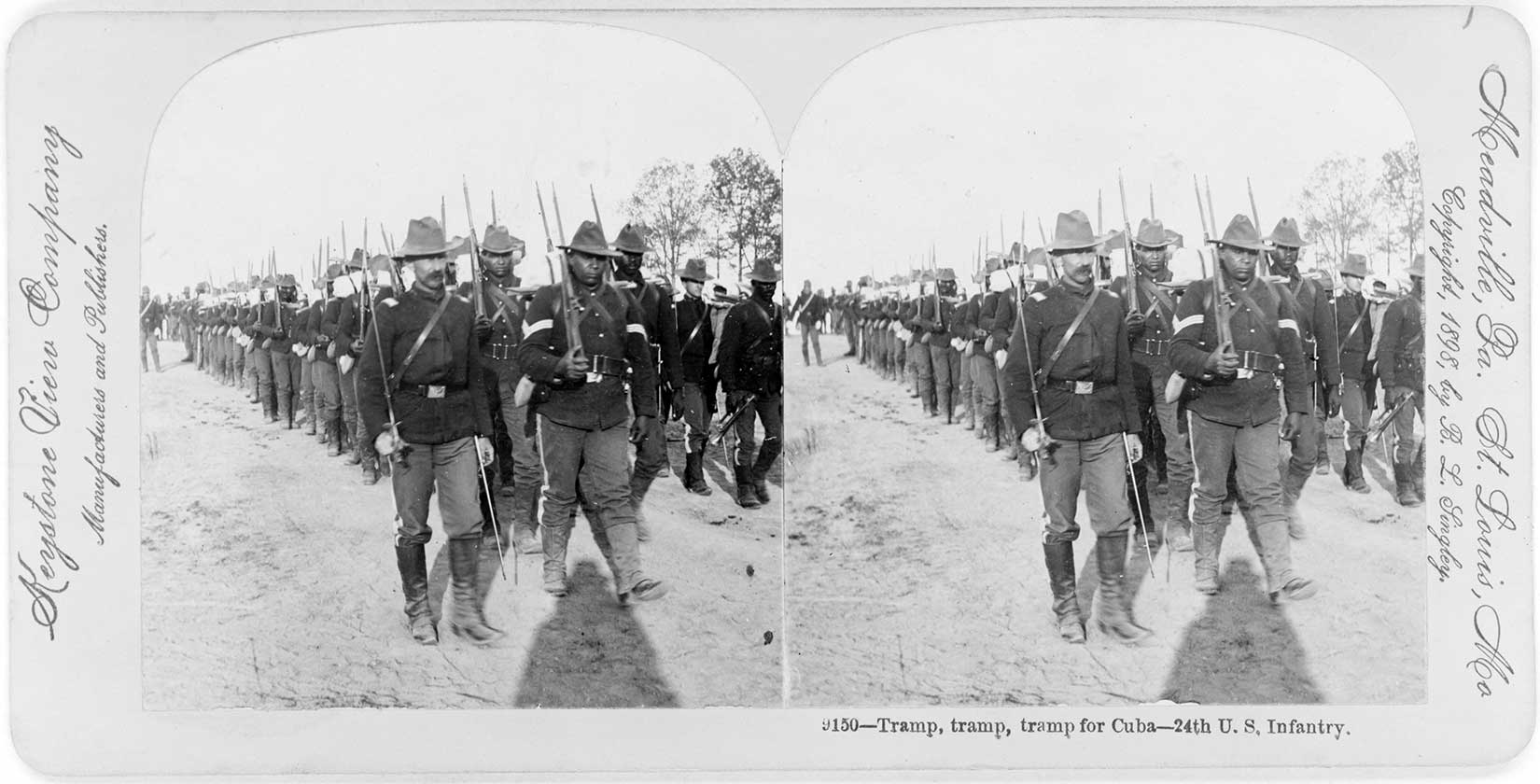

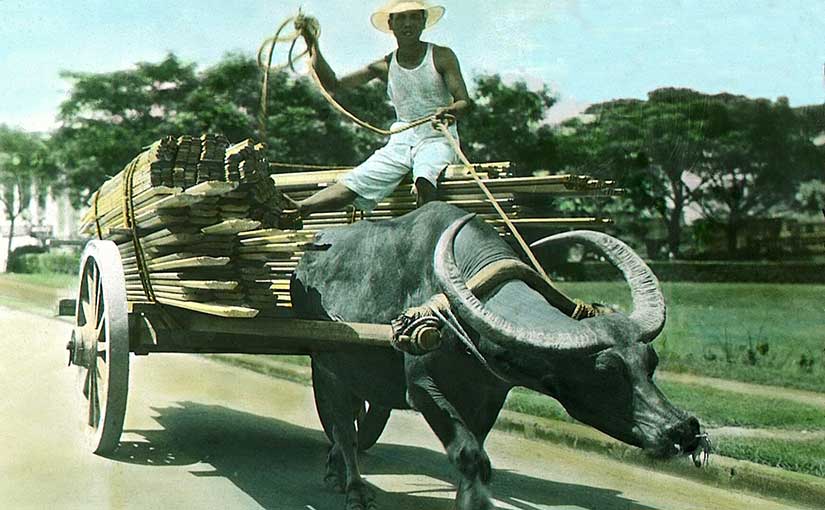

The outsiders of concern are the Americans. The ancients of Samkad’s village knew that the Philippine-American War was raging, but its irrelevance to their daily life shows how distinct their society was from that of the lowlands.

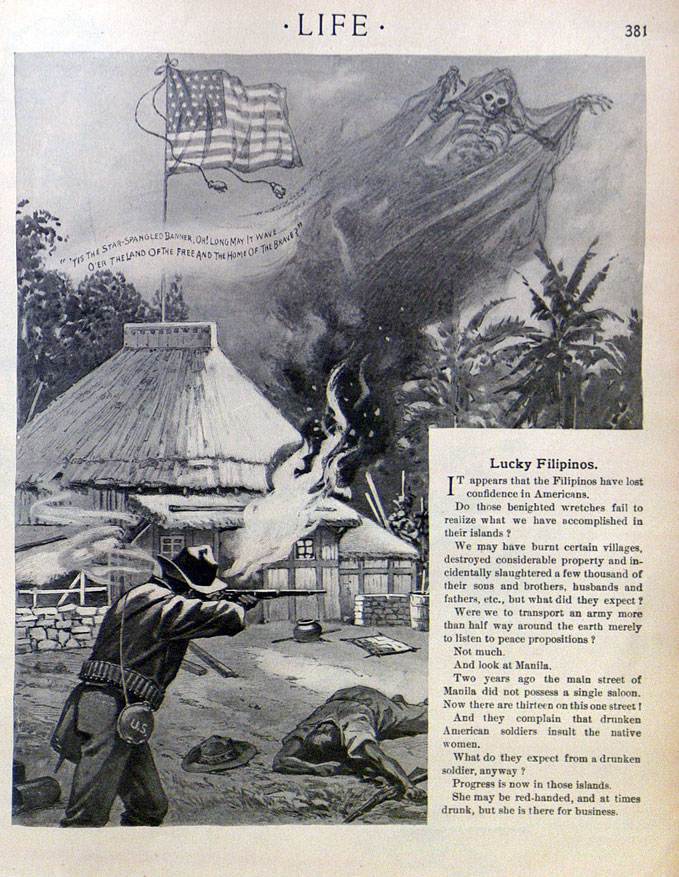

Samkad had no idea about any of what was happening down the mountain, which is probably a good starting point for most American readers. Gourlay is careful not to downplay imperialism and violence, but the book is not unnecessarily traumatizing for younger readers—though each family and reader needs to make that decision on their own. I am not an expert on the middle school age group, but others have deemed it age-appropriate, and it is published in the US by Scholastic. The text includes death of animals, torture (pulling a man behind a horse to injure but not kill him), corpses and dismembered bodies, and death. There is no sexual violence.

Not all Americans are bad in the book, but the only true heroes are Bontok. There is a teacher figure, Mister William, roughly based on Albert E. Jenks, I think, since the author referenced the letters and memoir of his wife, Maud. (I should say, it’s optimistic and generous portrayal of Jenks, if it is him.) William is too ineffectual to be a hero because he is unable to protect Samkad’s people from the dangers of his countrymen. And his English-language education carries with it the cultural imperialism of his fellow Thomasites. He is not a callous or cruel man, though.

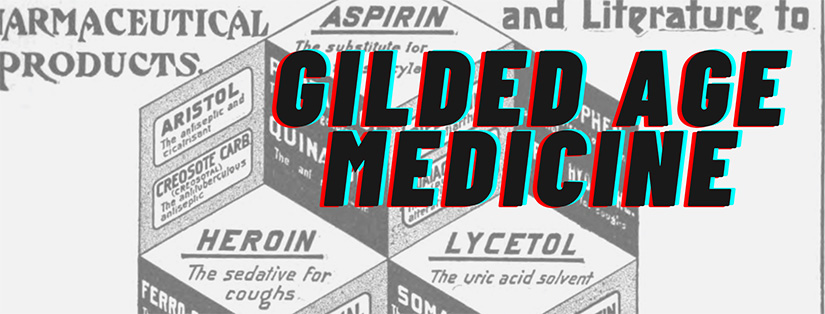

Beware soldiers bearing “gifts” of guns and candy, but you already knew that. The two soldiers who arrive treat the Cordillera people and culture as curiosities, and by this point the reader has been so well assimilated into village culture that the outrage is authentic and personal. That is important because the history of American science—and pseudo-science—in the Philippines is shocking. As Daniel Immerwahr revealed in How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, the overseas territories “functioned as laboratories, spaces for bold experimentation where ideas could be tried with practically no resistance, oversight, or consequences.”

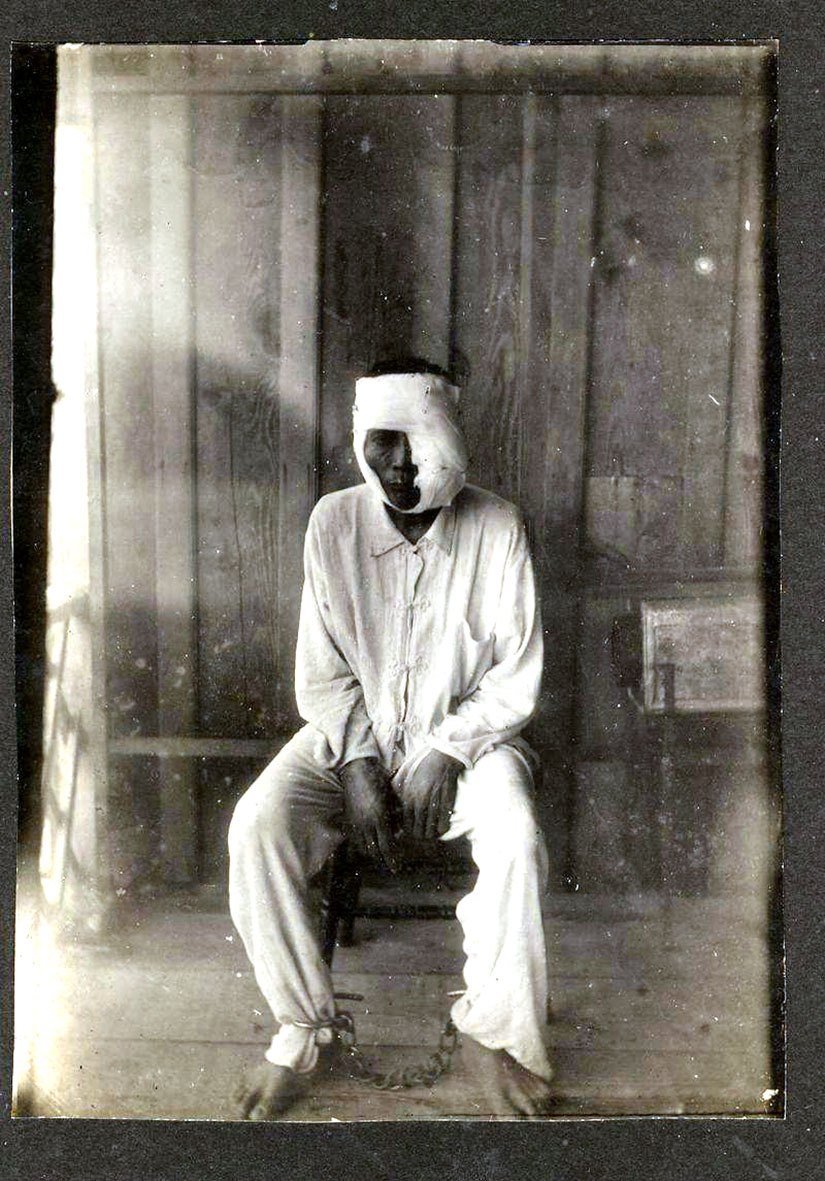

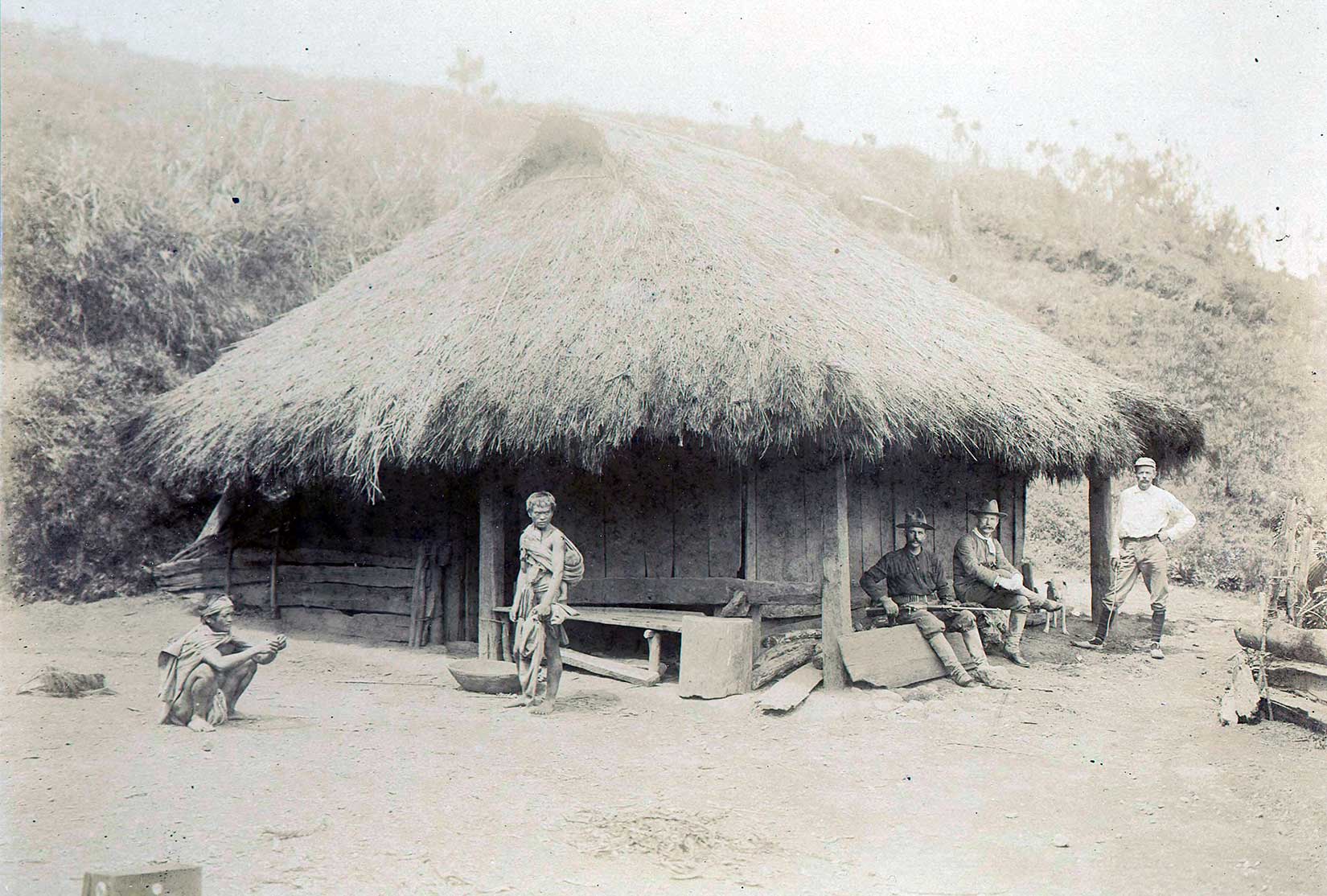

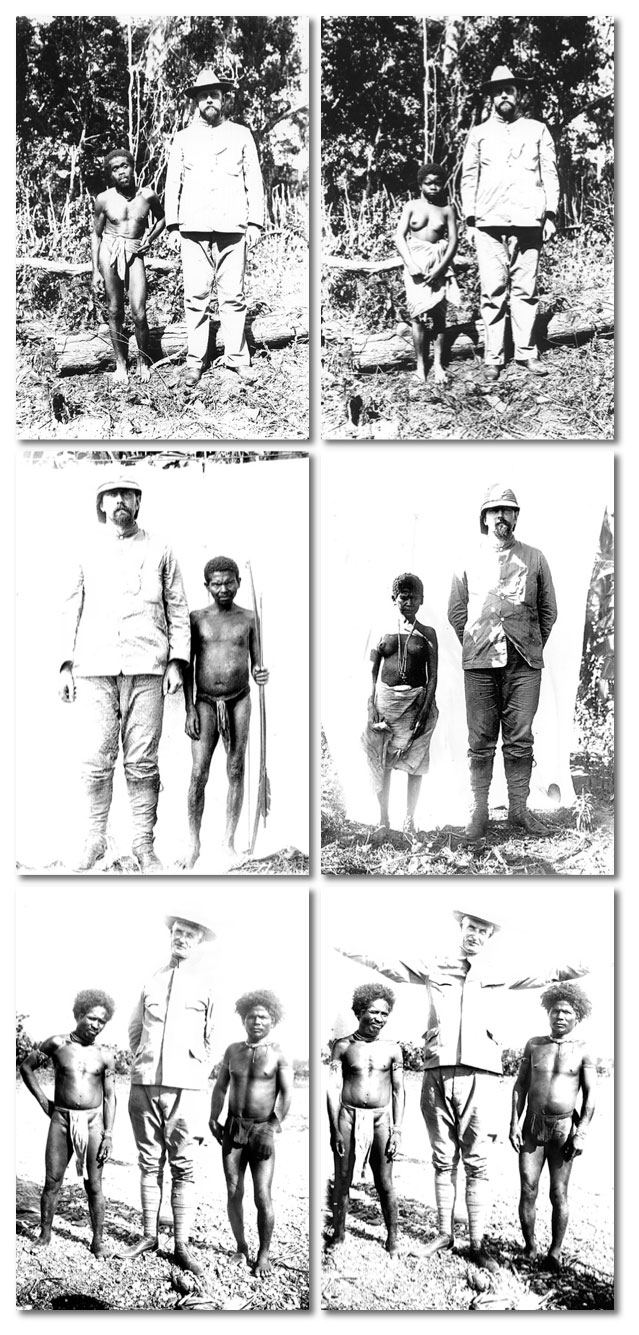

This material will form the background of my upcoming historical fiction novel, so I do not want to dive too deep into the subject here. A relevant example for this novel would be Worcester’s photographs of the Cordillera peoples as printed in National Geographic. Photographs were new to the magazine then, believe it or not, and Worcester’s images shaped the future of Nat Geo as well as the political disenfranchisement of the Filipino people. He used his racist “anthropological gaze” to measure the highlanders—using his own taller-than-American-average body as the yardstick and choosing the shortest people to stand next to him. The results were rigged. Gourlay hints at the role of cameras in the exploitation of the Cordillera peoples, allusions worth exploring in more detail with the help of the MIT Visualizing Cultures website on the topic.

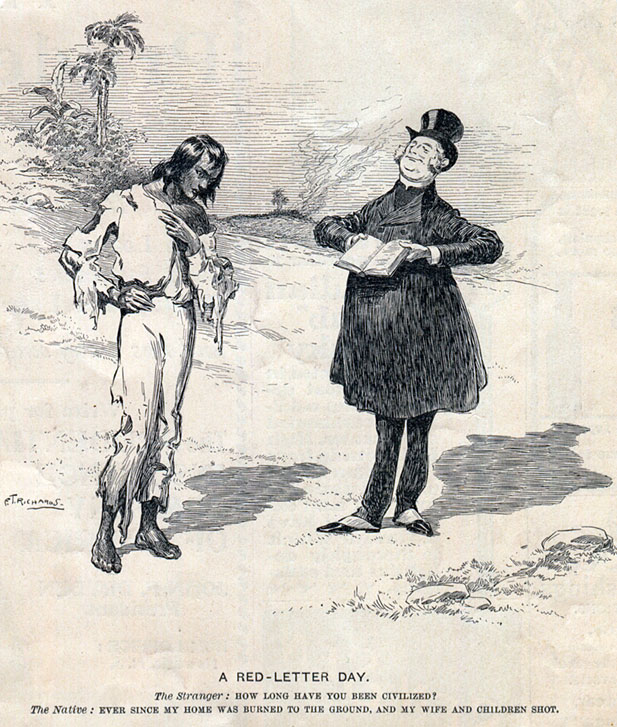

Worcester presented the Cordillera people as “primitive” and incapable of self-government, which then allowed him as Secretary of the Interior to assume legal control of all people, land, and resources in the area. Worcester was a one-man British East India Company. He was not even an anthropologist by training, though he claimed the title. He had a bachelor’s degree in zoology, specializing in ornithology—and the fact that he believed the two overlapped is telling, especially considering what happened next.

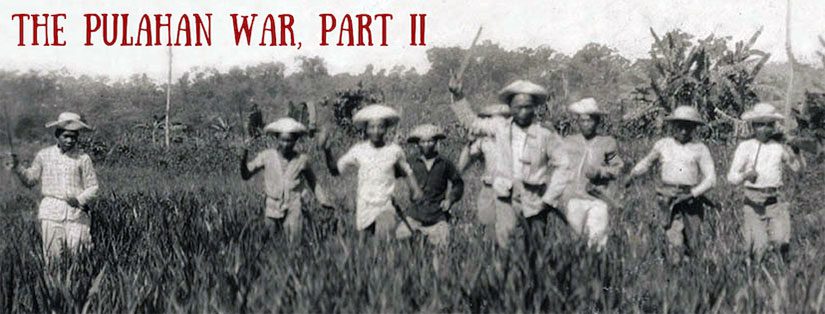

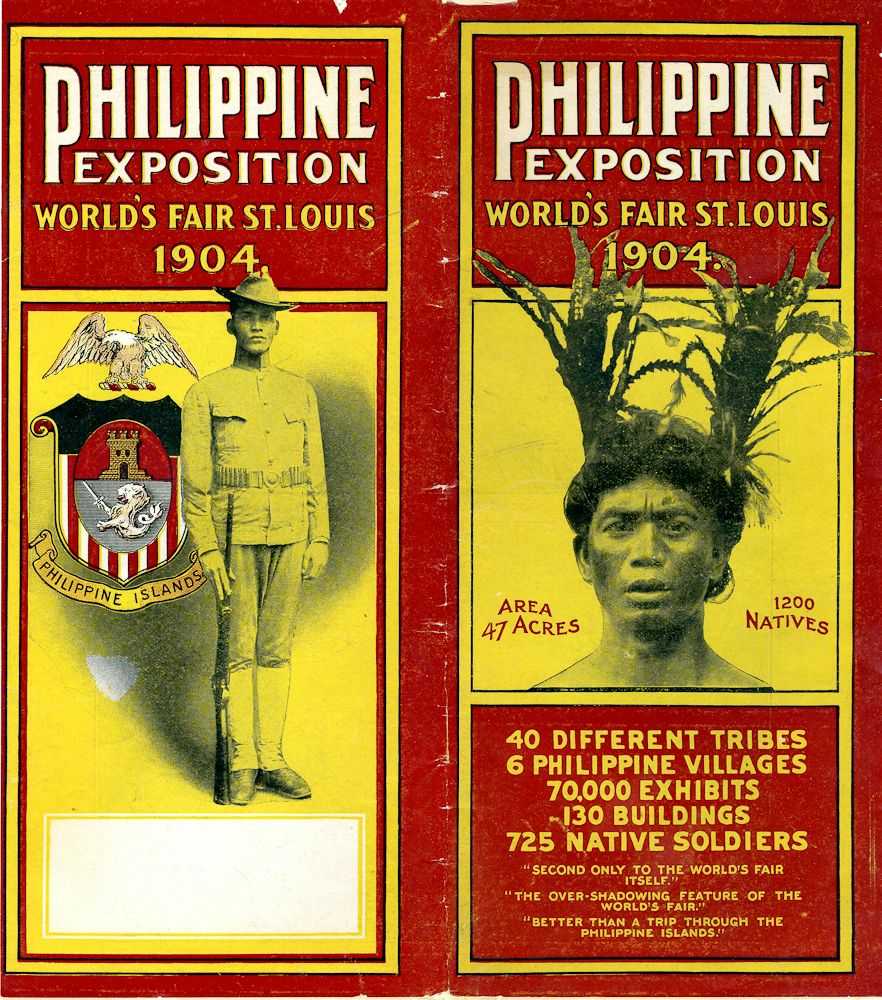

Entire villages of Cordillera peoples were transported to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. There, they and other Filipinos were subject to humiliating, fetishizing, and dehumanizing displays. For example, crowds were repulsed-yet-attracted to the rare ceremonial practice of dog-eating. The Cordillera peoples were required to butcher a canine each and every day for visitors, a cultural insult. (I lay this atrociously inhumane treatment of animals on the Americans who demanded the practice as “entertainment.”) For readers or teachers eager to know more, the Asian American Education Project has put together materials for further exploration.

If you would rather not know too much, this is the beauty of Bone Talk. It gives only a visceral snapshot of this history without going too deep in any one topic. As one reviewer said about the book, Gourlay “never overwhelms the reader with information or makes it feel artificial” but she has “clearly done her research.”

Gourlay also approached the issue of headhunting with care. She admitted that the Cordillera people she met “gave me the impression that they wanted to put headhunting firmly into the distant past.” It makes sense they would want to do so since headhunting was used by Worcester to justify his oppressive and self-interested administrative apparatus. However, as Gourlay found in her research, headhunting is not unheard of in white culture:

Britain, the book [Severed by Frances Larson], reminded me, has had a long tradition of severing heads. One famous head, Oliver Cromwell’s, became an attraction at small freak shows. It deteriorated down the centuries, losing an ear here and the tip of its nose there, before ending up in private hands. It wasn’t until 1960 that it occurred to someone to give Cromwell’s head a break. It was buried in Cambridge….Turns out, unshoed corners of the world do not have a monopoly on head chopping.

Talking about what are acceptable boundaries in war and law is a regular conversation in my classroom of mostly eighteen-year-olds. We see enough images of victims of napalm, white phosphorus, Agent Orange, nuclear bombs, nuclear testing, drone strikes, and enhanced interrogation that my students learn to question what form of killing is “civilized.”

Bone Talk is not an authoritative history of the Philippine-American War, nor should it be. It is a novel, a story set within this world but not encompassing all of it. After reading this book, though, I think every reader will want to learn more. I have lots of history here on this site, and Gourlay has put together a great set of resources appropriate for the age of her readers. More is needed, though. Americans need to know this history.

Fortunately, there is now more than a paragraph in high school textbooks on the invasion and seizure of the Philippines. Still, though, teachers do know enough about this history because they were not taught it; and students do not know enough to ask for more. If every student in the US read Bone Talk by the time they were in 9th grade, they might demand that more attention be given to American imperialism in the Pacific, especially the Philippines. A good book could be the most organic and effective way to combat imperial amnesia and American exceptionalism.