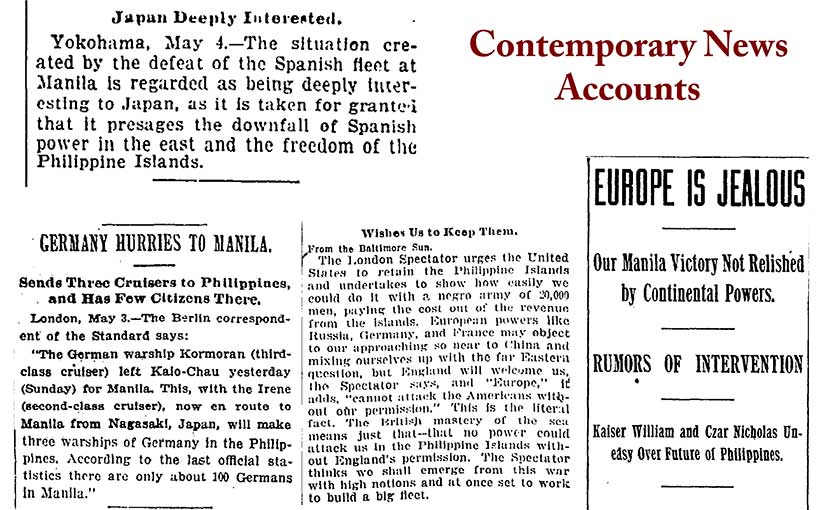

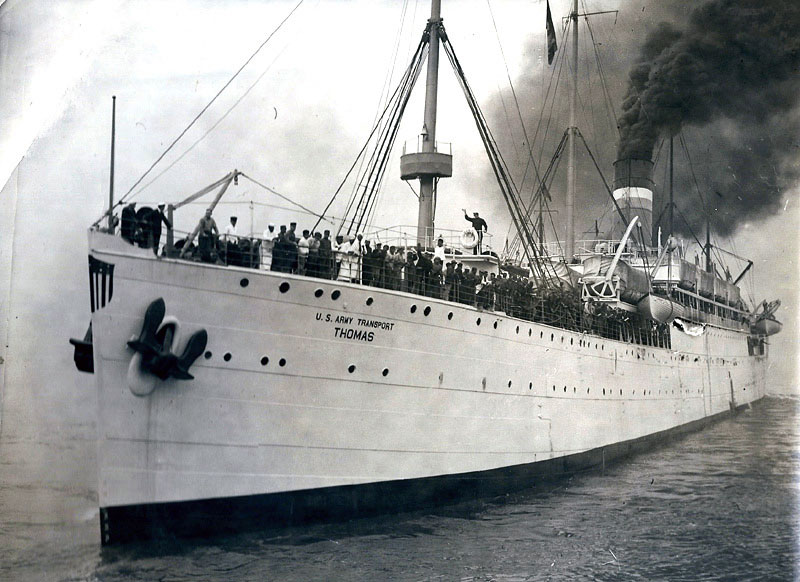

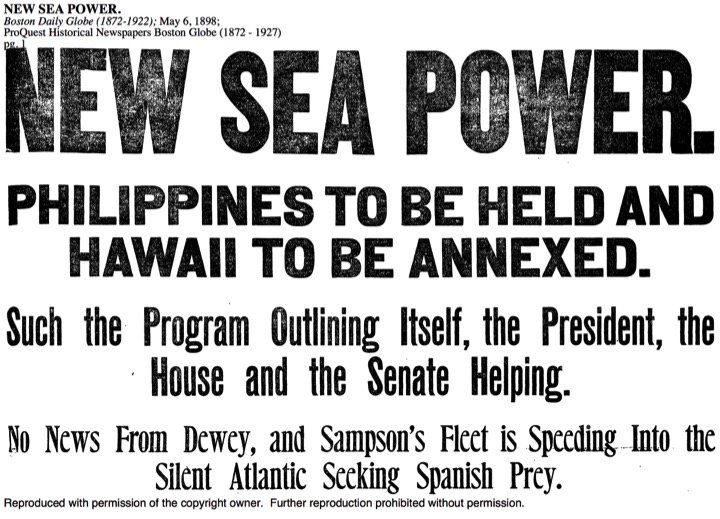

The Gilded Age was an age of New Imperialism. The age of empires began over five thousand years ago, so what was so “new” about imperialism, you ask? Well, there were new players: Germany, Japan, and the United States, to name three. (Though the US had been imperial from the very beginning, if you want to be honest about it. Thus began a long tradition of American imperial amnesia. If interested in more, check out Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire.) There were also new technologies: industrial transport and communication opened up the interiors of Africa and India, as well as tying together the disparate islands of the Pacific.

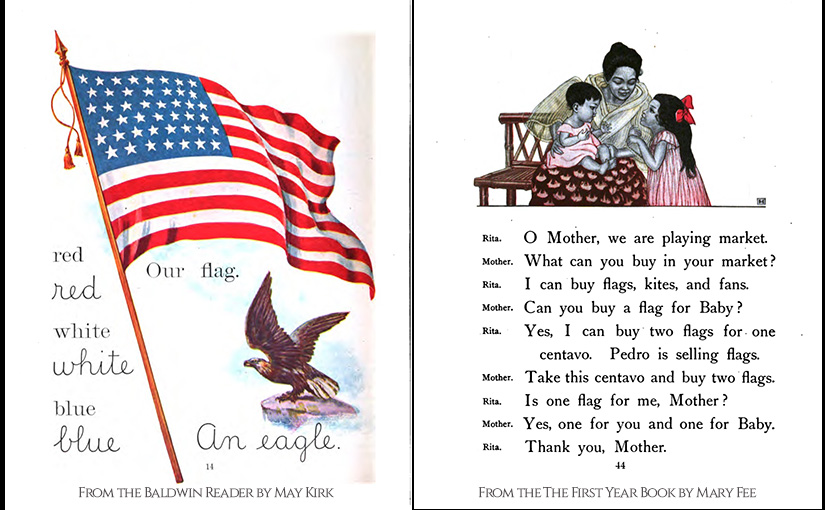

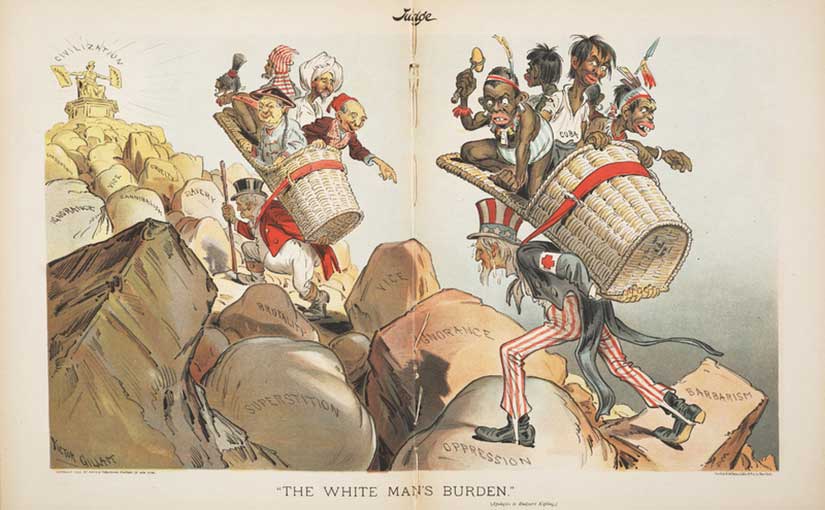

But one of the most puzzling aspects of New Imperialism was its doctrine: “Yes, we are here in your country, ruling your people, and pilfering your resources—but it is all meant to help you, not us.” Cue the rest of the world saying: “Are you kidding me?”

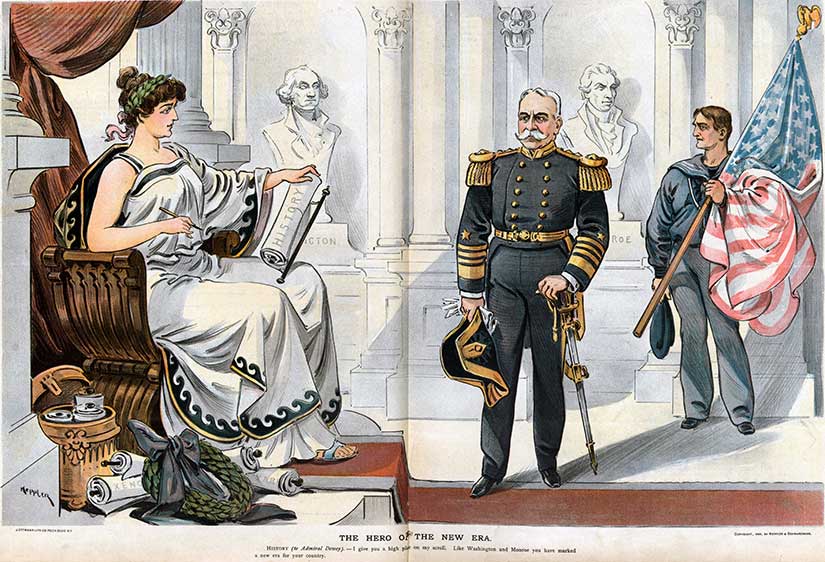

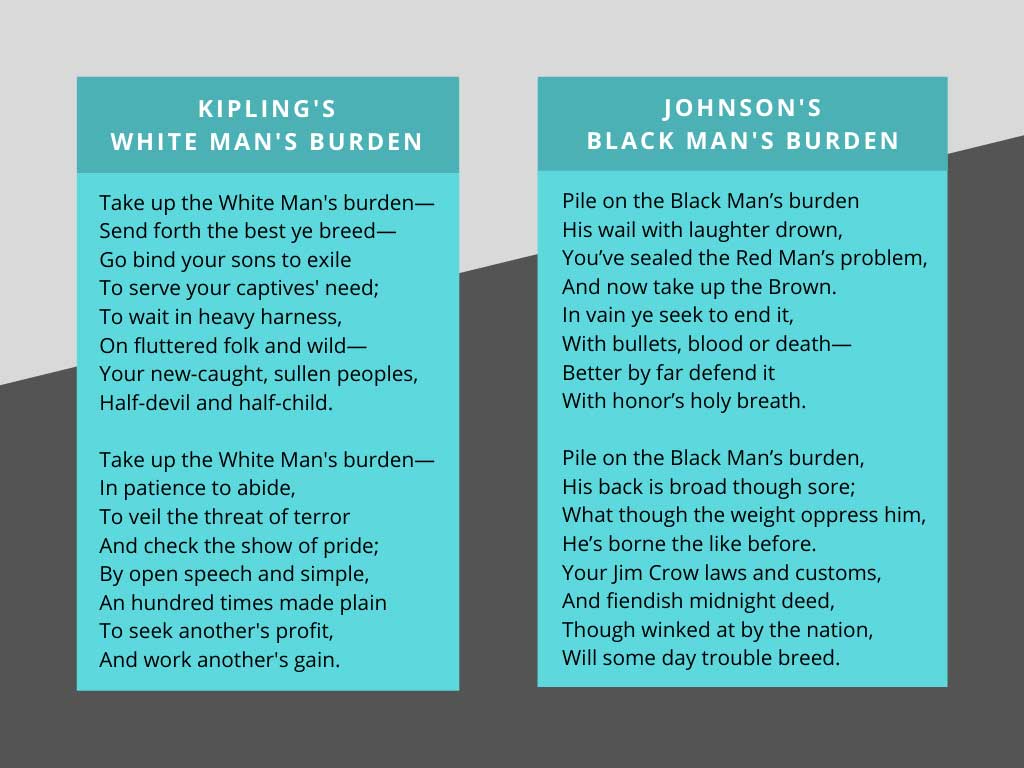

Well, no, the imperialists were not kidding. In fact, they wrote poetry about how much they were not kidding. In “The White Man’s Burden,” Rudyard Kipling famously instructed the Americans that it was their turn to play the game in 1899, after seizing Manila in the Spanish-American War.

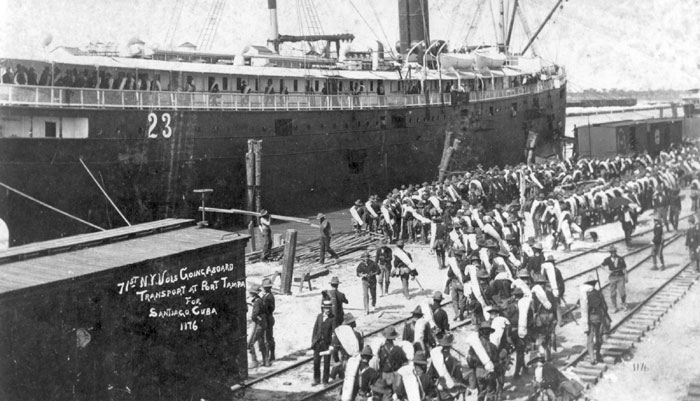

The people may hate you for it, Kipling was saying, but it is the Americans’ duty to colonize the Philippines and refashion the islands in the mold of Anglo-American civilization. African American editor Henry Theodore Johnson responded with “The Black Man’s Burden” (1899), which hit every note of opposition in the African American community, including: (1) the unnecessary nature of the war; to (2) how it fits into a long history of oppression of non-white peoples in the name of US expansion; and ends with (3) a reminder that Black Americans were already at war in their own country, not by their own choice. In the end, it would be African American regiments who would save the army in Cuba and serve in significant numbers in the Philippines, both in the US Army and in the Philippine Constabulary.

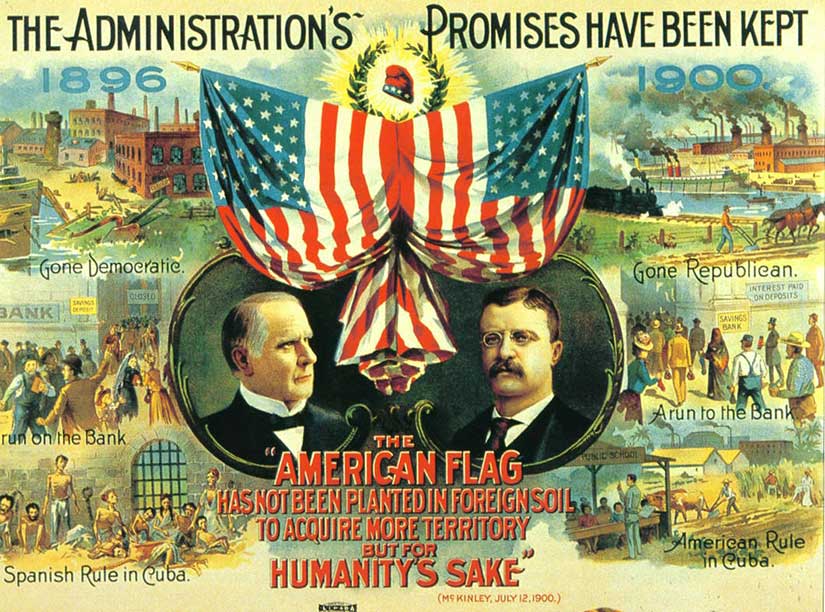

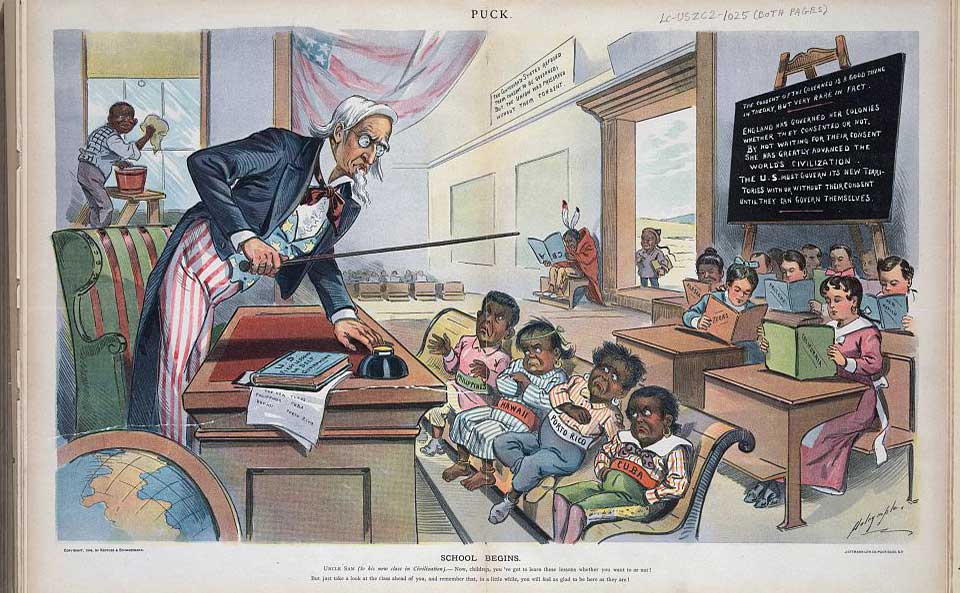

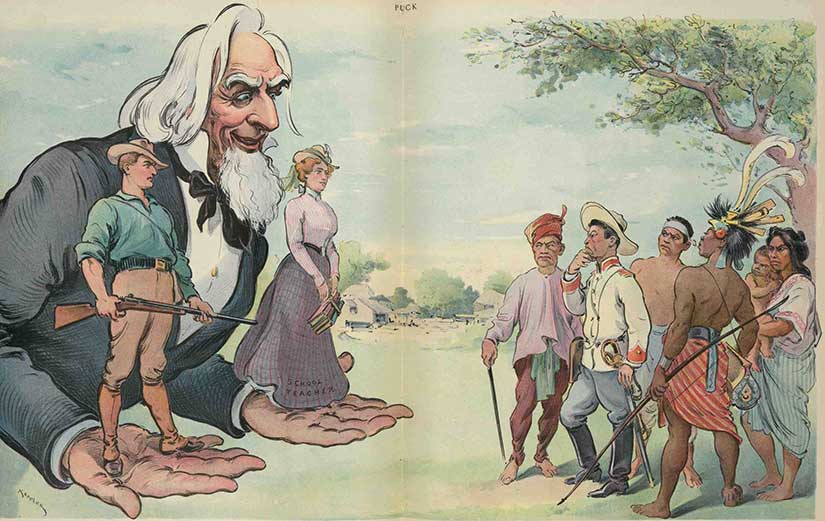

The authorities in the United States took up Kipling’s standard. They also believed the Philippines could be the Americans’ own foothold in Asia, an economic entrepôt to compete with the Great Powers in China. And, unlike those gauche Spaniards, the Americans would be enlightened rulers. President McKinley proclaimed:

…we come not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends, to protect the natives in their homes, in their employments, and in their personal and religious rights….[The American military must] win the confidence, respect and affection of the inhabitants of the Philippines…by proving to them that the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation, substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule. [emphasis mine]

William Howard Taft, the first civil governor of the Philippines (and eventual President of the United States), was credited with saying that the Filipinos would be our “Little Brown Brothers,” which—get this—was too generous for the tastes of most Americans. U.S. soldiers on the march in the Philippines sang in response: “He may be a brother of Big Bill Taft, but he ain’t no brother of mine.” (The ditty was eventually prohibited by officers because it did not make a great first impression, to say the least.)

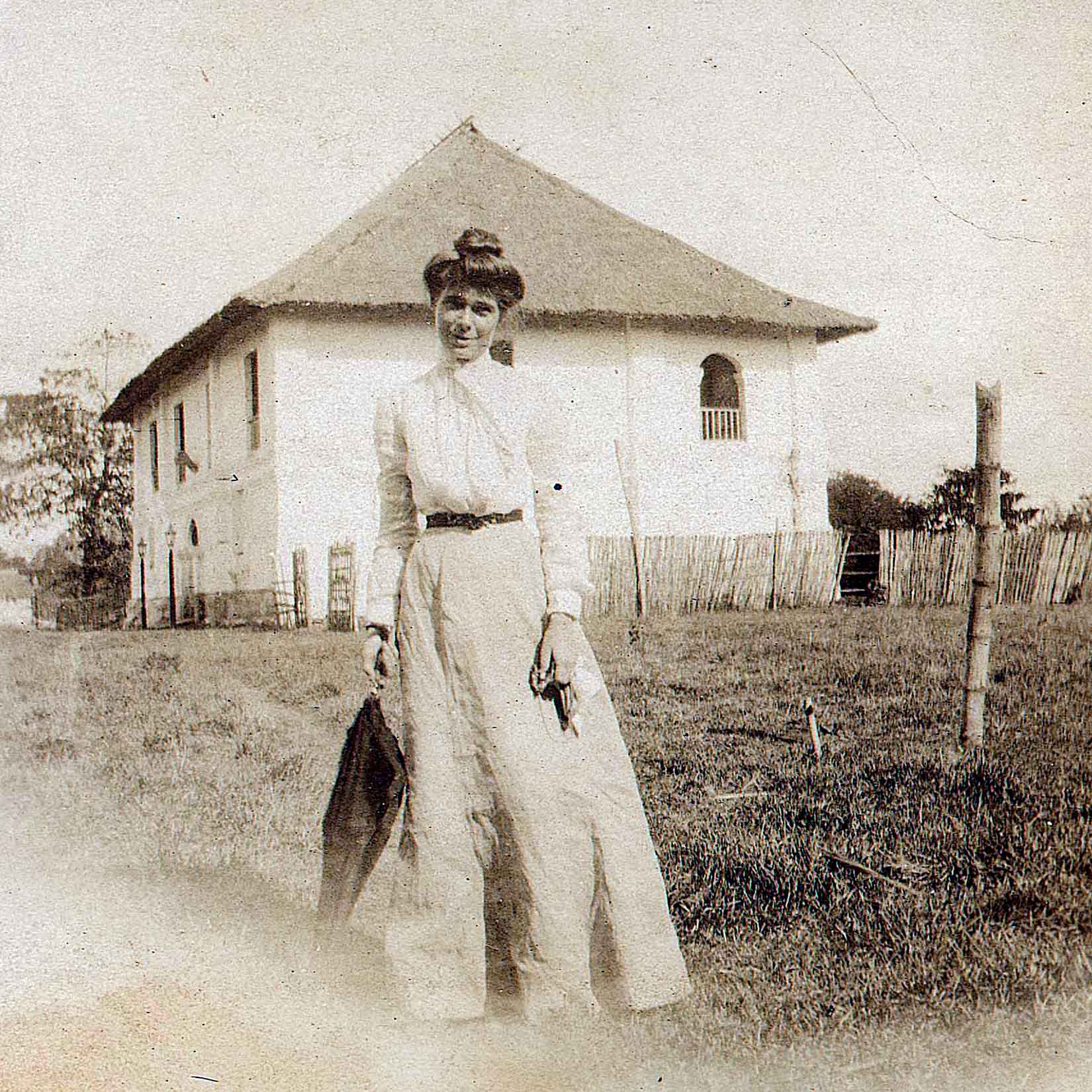

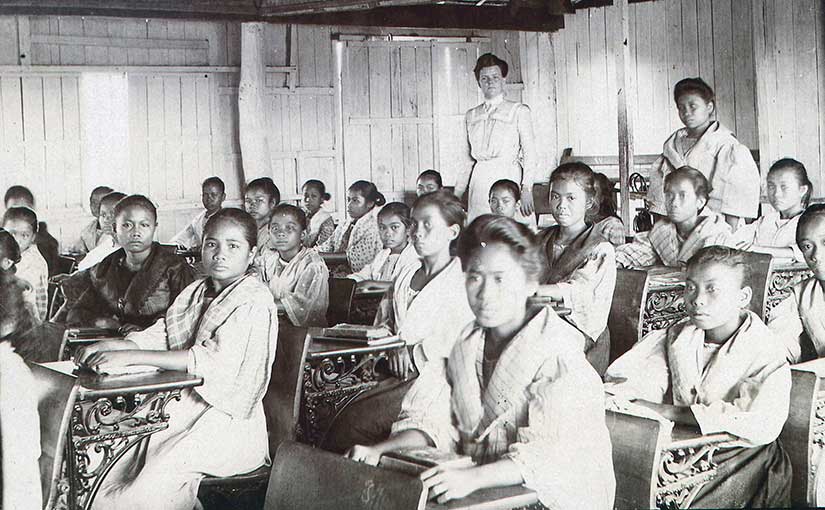

To be fair, there were some attempts at benevolence by the Americans. To name a few: the establishment of the first truly national and secular coeducational public school system in the islands; the creation of American university scholarships for the brightest Filipino youth; the building of ports, roads, telegraph lines, irrigation systems, hospitals, schools, and universities; the creation of a Filipino National Assembly; several Filipino Commissioners to advise the American governors; and a Supreme Court of the Philippines, led by a Filipino chief justice. This was not really democracy, but it was not the Belgian Congo, either.

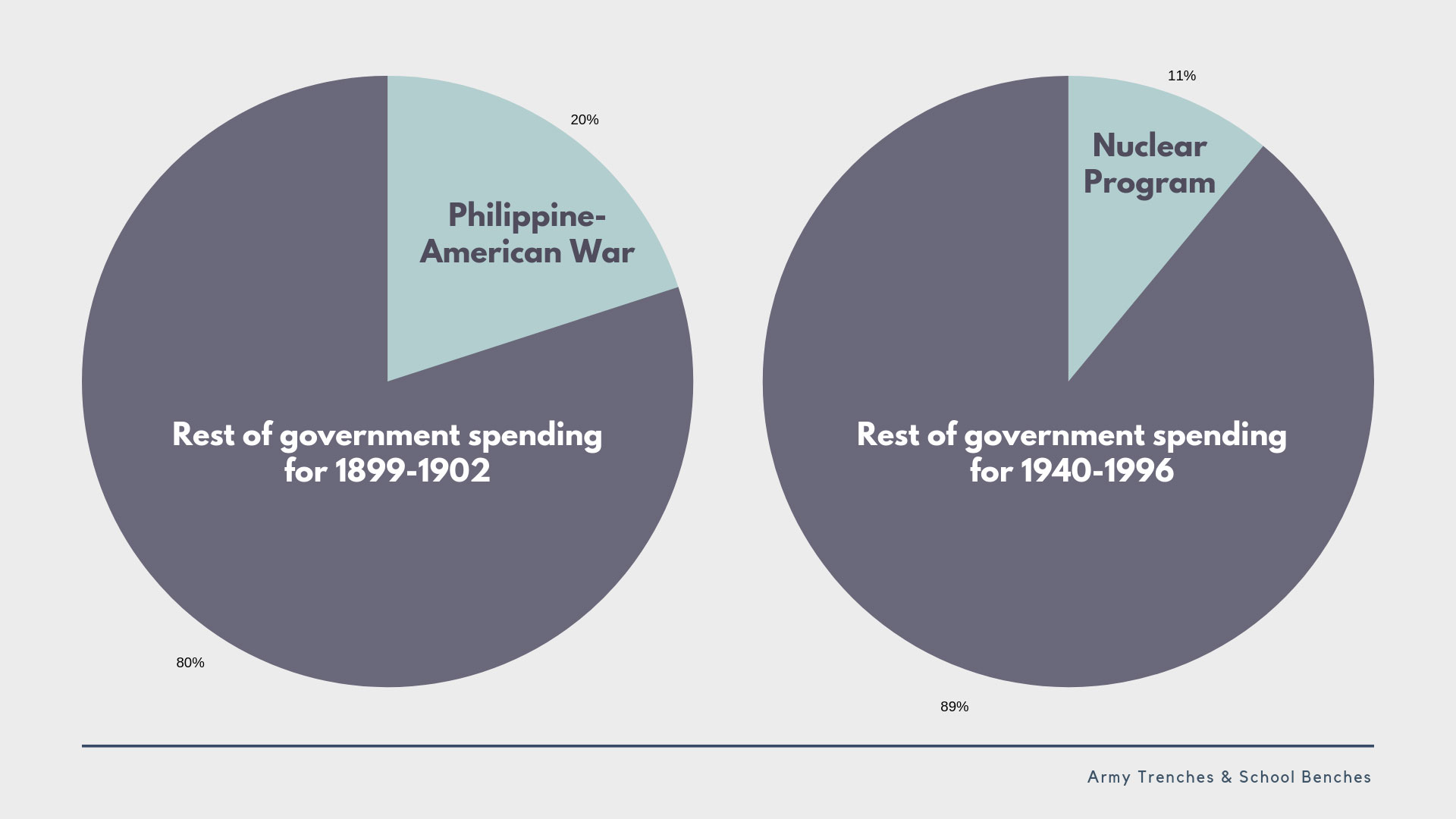

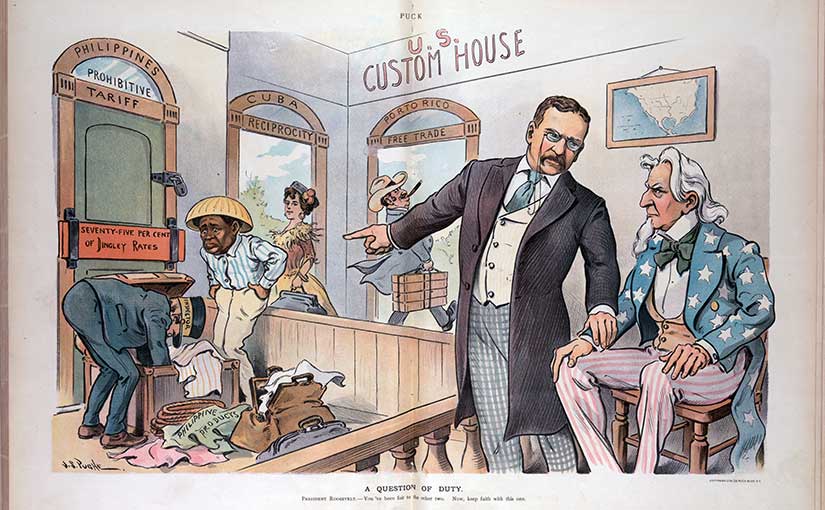

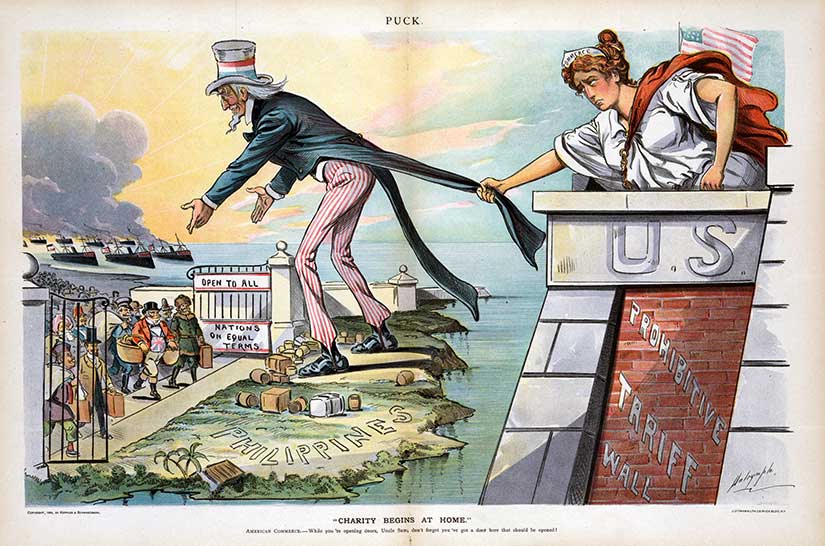

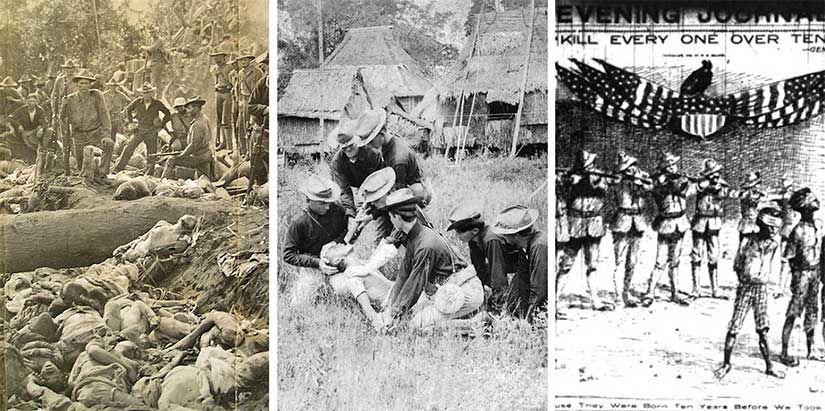

Still, there were plenty of ugly aspects to American rule in the Philippines, as you can see above. Occupation is always dirty. There was the Moro War, the water cure, and the Howling Wilderness of Samar. And, of course, there were the double-standard economic policies of the insular regime. The Americans set up a system by which American goods were sold in the Philippines tariff-free, but Filipino goods were taxed twice, both when they were exported from the Philippines and when they arrived in the United States. Where did that tariff revenue go? To pay the tab of the American administration, of course.

(Side note: The only US Treasury money spent for civilian reconstruction in the Philippines was the million dollars paid to farmers to compensate for the lost of their water buffalo to the rinderpest epidemic. The disease wasn’t the Americans’ fault, but the loss of 90% of these beasts of burden would hold economic progress back. Note that the US did not reimburse loss of carabao to military action or even deliberate slaughter in counterinsurgency actions.)

The hypocrisy of New Imperialism also prompted English writer and politician Henry Labouchère to write his own version of the “Brown Man’s Burden,” which included this stanza:

Pile on the brown man’s burden,

compel him to be free;

Let all your manifestoes

Reek with philanthropy.

And if with heathen folly

He dares your will dispute,

Then, in the name of freedom,

Don’t hesitate to shoot.

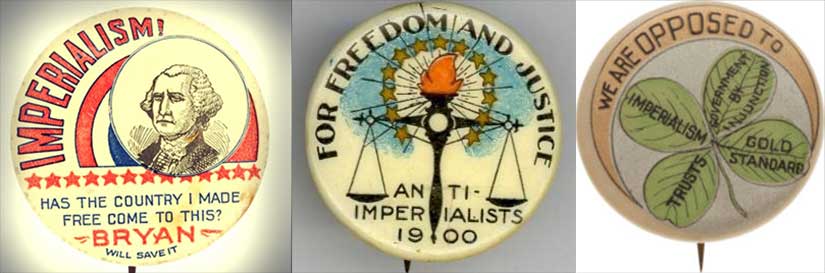

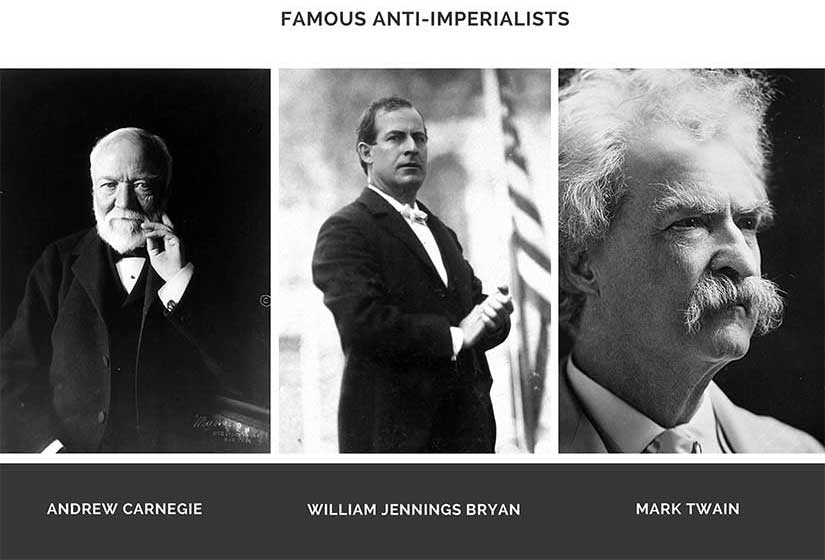

Before you pat Labouchère on the back for his progressive skewering of Kipling’s motives, do know that he was a homophobic campaigner whose most lasting legacy was the Labouchère Amendment that made all sexual activity between men a crime. (This is the law that Oscar Wilde and Alan Turing were prosecuted under.) And Labouchère was not the only anti-imperialist who might disappoint our modern sensibilities. Both Andrew Carnegie and William Jennings Bryan were anti-imperialists, but their opposition was actually based on racist visions of nationhood. Carnegie wanted us to only take land that would “produce Americans, and not foreign races,” and Bryan worried about Chinese and Filipino immigration “exciting a friction and a race prejudice” that would damage America’s homogeneity.

In fact, some of the most vociferous anti-imperialists were racist Southern Democrats, many of them ex-Confederates. A former major in the Confederate Army, Senator John W. Daniel is quoted in the Congressional Record as saying:

We are asked to annex to the United States a witch’s caldron. . . . We are not only asked to annex the caldron and make it a part of our great, broad, Christian, Anglo-Saxon, American land, but we are asked also to annex the contents and take this brew—mixed races, Chinese, Japanese, Malay, Negritos—anybody who has come along in three hundred years, in all of their concatenations and colors; and the travelers who have been there tell us and have written in the books that they are not only of all hues and colors, but there are spotted people there, and, what I have never heard of in any other country, there are striped people there with zebra signs upon them. This mess of Asiatic pottage 7,000 miles from the United States, in a land that we can not colonize and can not inhabit, we are told today by the fortune of a righteous war waged for liberty, for the ascendency of the Declaration of Independence, for the gift of freedom to an adjoining State, we must take up and annex and combine with our own blood, and with our own people, and consecrate them with the oil of American citizenship.

Before you despair, though, let’s move onto Mark Twain, who “updated” the lyrics of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, Julia Howe’s abolitionist hymn, to more properly reflect what he felt Americans had been doing in the Philippines:

Mine eyes have seen the orgy of the launching of the Sword;

He is searching out the hoardings where the stranger’s wealth is stored;

He hath loosed his fateful lightnings, and with woe and death has scored;

His lust is marching on.

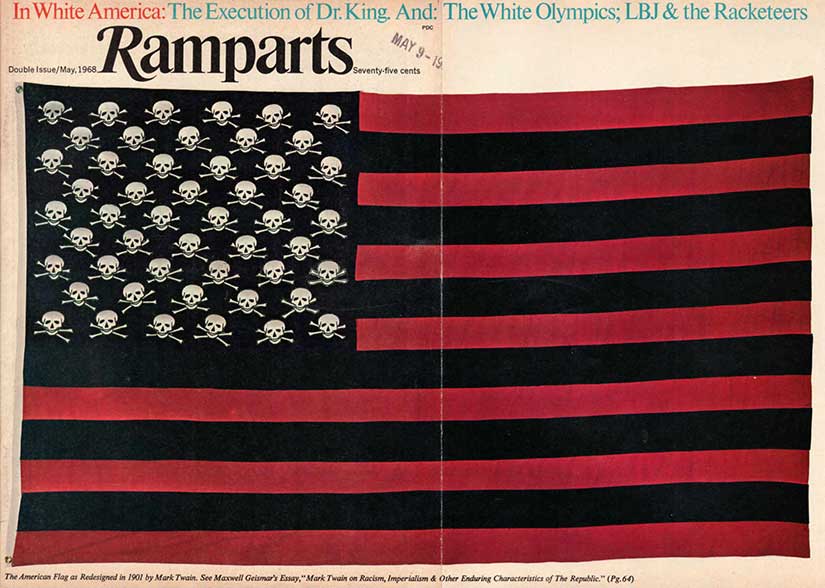

And, if that was not enough, Twain redesigned the American flag to include skulls and crossbones instead of stars. His essay “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” is a brilliant piece of political satire:

Shall we? That is, shall we go on conferring our Civilization upon the peoples that sit in darkness, or shall we give those poor things a rest? Shall we bang right ahead in our old-time, loud, pious way, and commit the new century to the game; or shall we sober up and sit down and think it over first? Would it not be prudent to get our Civilization-tools together, and see how much stock is left on hand in the way of Glass Beads and Theology, and Maxim Guns and Hymn Books, and Trade-Gin and Torches of Progress and Enlightenment (patent adjustable ones, good to fire villages with, upon occasion), and balance the books, and arrive at the profit and loss, so that we may intelligently decide whether to continue the business or sell out the property and start a new Civilization Scheme on the proceeds?

Both Johnson and Twain give us some faith that not every American bought into the plunder-but-call-it-progress ideology of New Imperialism. But most did.

Featured image at the top of the page is the 20 March 1901 cover of Puck. Read more about New Imperialism here.