What did the Common App look like for Filipinos in 1905? Could you gain admission, let alone earn a scholarship?

While much of the American educational system in the Philippines was geared around a racist “industrial” model—in other words, teaching Filipinos the skills they needed to produce goods for American businesses—there was an advanced track to train the best and brightest for government work.

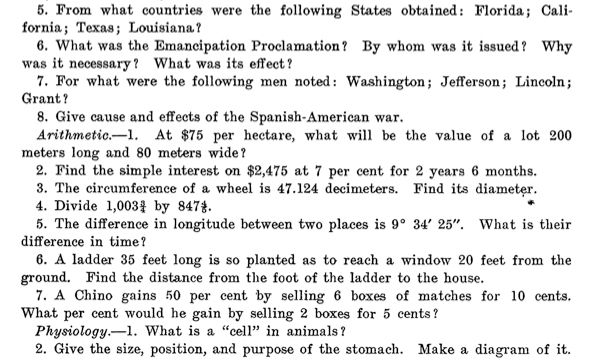

Here’s how it worked: young men and women aged 16-21 took an examination that included questions on grammar, geography, American history, math, and physiology. For example: “Give three differences between young rivers and old rivers.” Or “Name and describe three early and successful North American settlements.” Or “Divide 1003 3/4 by 847 4/5.” (Without a calculator, mind you. I could do it, but not happily. Multiply by the reciprocal, right? I’m already bored…)

Where did such smart kids come from? Everywhere, actually. Even, or especially, the provinces. Despite its flaws, the American Bureau of Education did set up a public, secular, and coeducational system throughout the Philippines. Higher education had been open to elites under the Spanish, but for barangay children this was a brand new opportunity. The whole point of education, according to the 1903 census, was to pacify the islands—to give parents a good reason to set down arms and take a chance with Yankee rule.

And in order to truly “benevolently assimilate” these future elites, the Americans would need to shape their minds and careers in the American heartland: Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Iowa, New York, and Minnesota mainly, with a few in California, of course. The first group of 100 boys of “good moral character” and “sound physical condition” were selected: 75 from public schools throughout the islands and 25 at large by executive committee. In succeeding years, much smaller numbers would be chosen, a dozen or two at a time, including women. Each student was required to take an oath of allegiance to the United States before enrolling in the program.

With $500 per year to cover expenses—two-thirds of an average American family’s income at the time—the Filipinos could live well in the smaller towns of the American Midwest. They went to football games, joined fraternities, and went out on dates. (More on that later.) Many did a year in an American high school first to polish their English, and then did three to four years of advanced study. Author Mario Orosa estimates that the Insular (colonial) Government spent the modern equivalent $50,000 or more educating his father in Cincinnati.

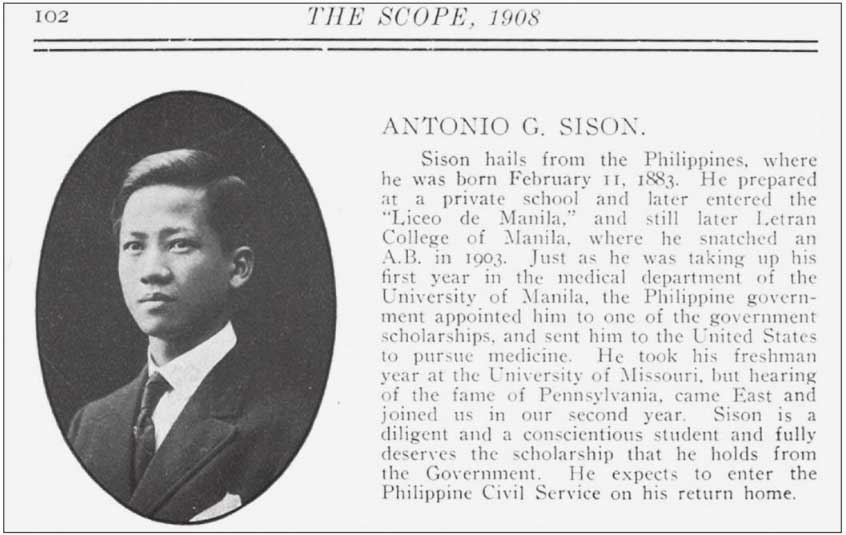

Students could study whatever subjects they wished, but they would have to put this knowledge to use: each year of study in the United States meant a year working (with a full salary) for the Insular Government in the fields of education, medicine, forestry, engineering, textiles, or finance.

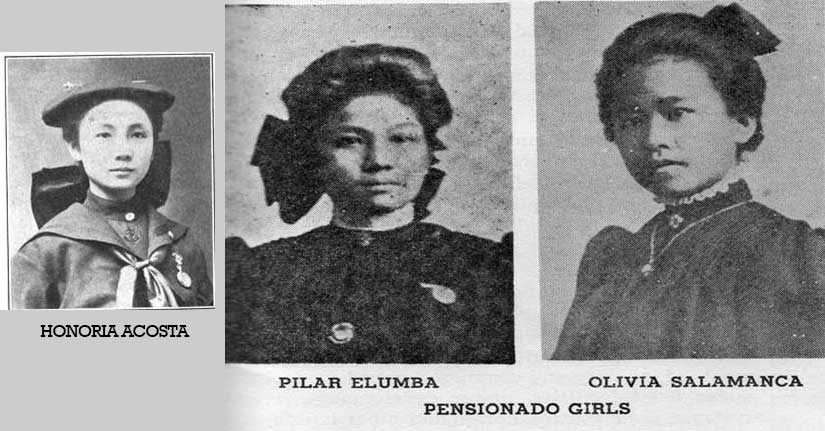

In 1905, the highest scoring tester was a 12-year old girl named Felisberta Asturias. She may have been too young to go to the U.S., but the next highest scorer, Honoria Acosta from Dagupan, would become the first Filipino woman to graduate from an American university (Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania), and therefore the first Filipino female physician, as well as the founder of obstetrics and gynecology as a specialized field in the Philippines.

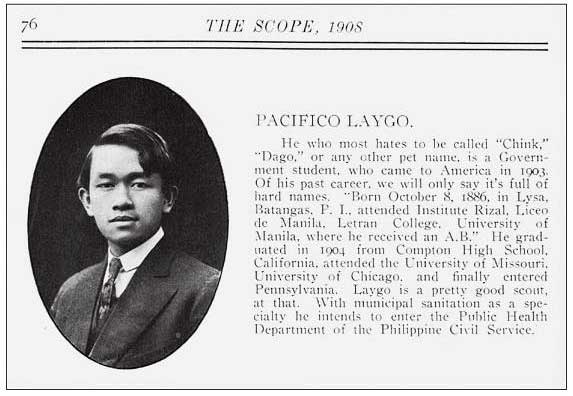

Winning the scholarship was only half the battle, though. While in the United States, these students encountered their fair share of racism, as Pacifico Laygo’s yearbook entry illustrates.

How tiring it is, this insistence of Lagyo’s that he not be called a racial slur! But he is a “pretty good scout, at that,” so it’s okay, right? That’s only patronizing, not explicitly racist. At Cornell, Apolinario Balthazar, one of those who would be responsible for rebuilding Manila after World War II, was told by one American bully that “no matter how much you wash your hands, you cannot change your color.” Southern states just outright refused to host the Filipino students.

Newspapers got into the act, too. According to Victor Román Mendoza, the Omaha Daily Bee downplayed the athletic achievements of the local Filipinos students, saying: “That Filipino students are showing well as runners in college athletic events is not surprising to those who remember the good races won by the followers of Aguinaldo during the insurrection.”

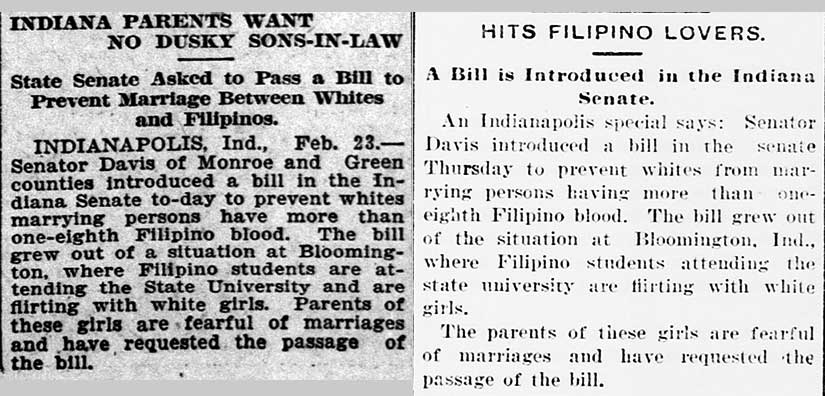

Maybe it wasn’t all bad, though. There were the romances, especially those between Filipino men (the majority of pensionados) and American women. James Charles Araneta—yes, those Aranetas—stayed two years with the Newell family in Berkeley, California, and when he left he took their sixteen-year old daughter, Lillian, with him. As the Aranetas were both wealthy and well-connected in the new American administration—Negrense sugar barons!—the news reports on the match were both breathless and lurid at the same time. It was national news, from the front page of the San Francisco Call to the Des Moines Register to the Pittsburgh Press.

If the groom was less flush, though, an otherwise respectable marriage might be kept secret from friends and family on both sides. That wasn’t enough to stop it from happening, though, so officials in Indiana tried (and failed) to pass a law against whites marrying anyone with more than one-eighth Filipino blood. They portrayed the pensionados not as scholars but as “slick” operators eager to “stain America’s future brown,” in the words of University of Michigan English professor Ruby C. Tapia. This was the world Javier and Georgina had to fight against, and I know the racism in the book was hard for some to read, but reality was far uglier.

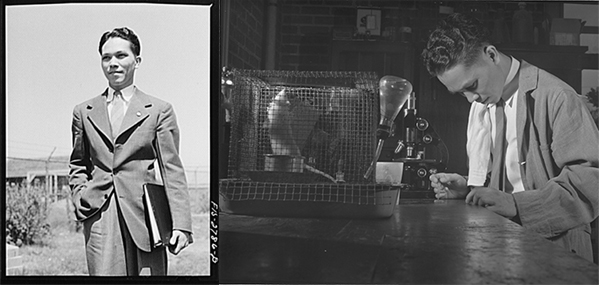

Proving that you can never catch a break, returning home was not easy for the Filipinos, either. Generally, pensionados were given immediate supervisory positions over their countrymen, who in turn resented the “Amboys.” On the other hand, the Amboys were not American enough for the Americans in Manila, who refused to admit the pensionados to their private clubs, no matter how Midwestern their education, manners, or dress. Many of these men and women would be pioneers in their fields and are heroes to us now, but at the time they struggled to fit in anywhere.

Eventually, the pensionados would make their own place in society—and it was an exalted one. While only a small part of the population, these 700 men and women educated from 1903-1945 would shape the Philippine Commonwealth and Republic. They became cabinet members, department secretaries, university presidents, deans and professors, designers of national irrigation systems, builders of bridges, lawyers, justices, titans of industry, doctors, archbishops, and, unfortunately, martyrs to the Japanese occupation. Mario Orosa has an extensive list by name and short biography, and it is an impressive read.

The pensionado system will feature in two of my upcoming books, but only one character will pass the test and take the scholarship. Can you guess who? Maybe I shouldn’t tell you. It will spoil the surprise.

Featured image of Philippine Illini from the University of Illinois in 1919.