Baseball arrived in the Philippines with Commodore George Dewey in May 1898. After sinking the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay and taking over Cavite Naval Base, the Olympia‘s team, the Diamond Diggers, played the first Army-Navy game on Philippine soil. I could not find out who won.

Though basketball proved a more popular sport amongst Filipinos in the long term, baseball is a fitting metaphor for the entire American occupation.

American justifications for imperialism were racist right out of the gate. The Yanks claimed to be “benevolently assimilating” the Filipinos, and assimilation included sport. General Franklin Bell (of reconcentrado fame) claimed that “baseball had done more to civilize Filipinos than anything else,” and the Manila Times called it a “regenerating influence, or power for good” (quoted in Gems 112).

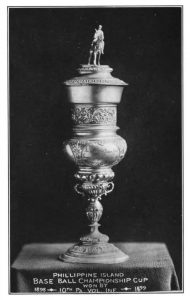

Colonial racism was not limited to Filipinos, either. The Americans mistreated their own, including the 24th and 25th Infantries, both African American regiments. Jim Crow America came to Manila, including all-white barber shops and all-white baseball leagues. The 25th—who played for “Money, marbles, or chalk, money preferred”—got a small bit of revenge by winning the island championships for four years in a row.

Baseball was a part of the Thomasite educational program from the beginning. The teachers hoped that it would replace cockfighting, though that goal ultimately proved too ambitious. Still, baseball did catch on. One Thomasite reported: “We first got hold of the Jolo boys through baseball” (quoted in Elias 44). Because English was the language of the diamond, it was seen as a way to advance a holistic curriculum. According to public health commissioner, Victor Heiser:

…a group of yelling Igorots (mountain tribespeople) had been seen playing baseball in a remote clearing. The catcher wore only a G-string and mask, and the runner on first started for second amid cries of: “Slide, you son of a bitch, slide!”

This was all military policy, when you get down to it. Remember that public schools were started because “no measure would so quickly promote the pacification of the islands,” according to the colonial government’s 1903 Census. In other words, Americans wanted to rule with books, not Krags. This is called civic action—or, as it was known in the Philippines, attraction. (And it is better than drones, but if those are your two choices please re-examine all your assumptions.) Baseball was a “weapon” in the search for peace. The Los Angeles Times claimed that “The American athletes will teach them that the bat is more powerful than the bolo” (quoted in Franks 17).

Baseball may have provided a romantic substitution as well. The indigenous tradition of the Cordillera mountaineers (often called Igorots) suggested that a prospective groom could impress his bride’s family with a “scalp of their bitterest enemy,” according to American sportswriter Ernie Harwell. Conveniently, baseball provided an alternative: home runs: “Americans, acting as muscle-bound cupids, often played simple grounders and easy outs into home runs so their Filipino friends could escape bachelorhood” (quoted in Elias 45). (In Sugar Moon, Ben Potter needs eight runs in a pick-up baseball game to earn Allegra’s hand, but no one takes it easy on him.)

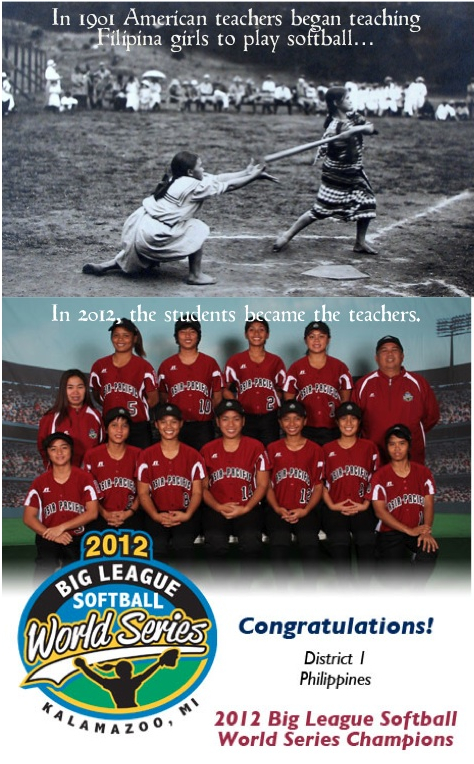

Though Allegra was not much of a player herself, girls could and did play the game. This followed the Thomasite emphasis on coeducation, maybe the best thing the Americans brought to the Philippines. Both boys and girls still play to great success in the Philippines. Youth league world championships often feature Filipino teams as the representative champions of Asia, and sometimes they win the whole darned thing: