By now you have heard the results of the 2016 election: marijuana won. Well, at least in four states. California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada legalized recreational use. Also, Arkansas, Florida, and North Dakota legalized certain medical uses. You can see which way the smoke is blowing. Maine’s marijuana question passed by less than one percent of the vote, but that ambivalence does not express the sea-change in American attitudes towards pot. According to the Washington Post, more than 1 in 5 Americans now “now live in states where the recreational use of marijuana is, or soon will be, legal.”

But how long has it been illegal? Would it surprise you to know only 80 years, since 1937? In fact, would it surprise you know that during the colonial era, cannabis was not only legal but—in 1619— required of all farmers in Virginia to plant? And that cannabis served as legal tender in Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland? This may be stretching the truth a little, but only a little. I am conflating two strains of plants: hemp and marijuana. What is the difference? Well, both are the same species—cannabis sativa—but marijuana has significantly higher levels of the intoxicant delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). However, until recently, hemp has been more commercially productive. Its strong fibers can be used for rope, paper, textiles, plastic, food, biofuel, and animal feed.

In the colonial era, it was cordage and textile uses that made cannabis so versatile. Not that people throughout history did not know of the more recreational properties, of course. Throughout Asia and Europe, cannabis was used for pain relief, spiritual escapes, and a nice little high after work. But we do not need to go that far back. After all, this blog focuses on the Gilded Age at the turn of the twentieth century—and this is when attitudes towards marijuana changed.

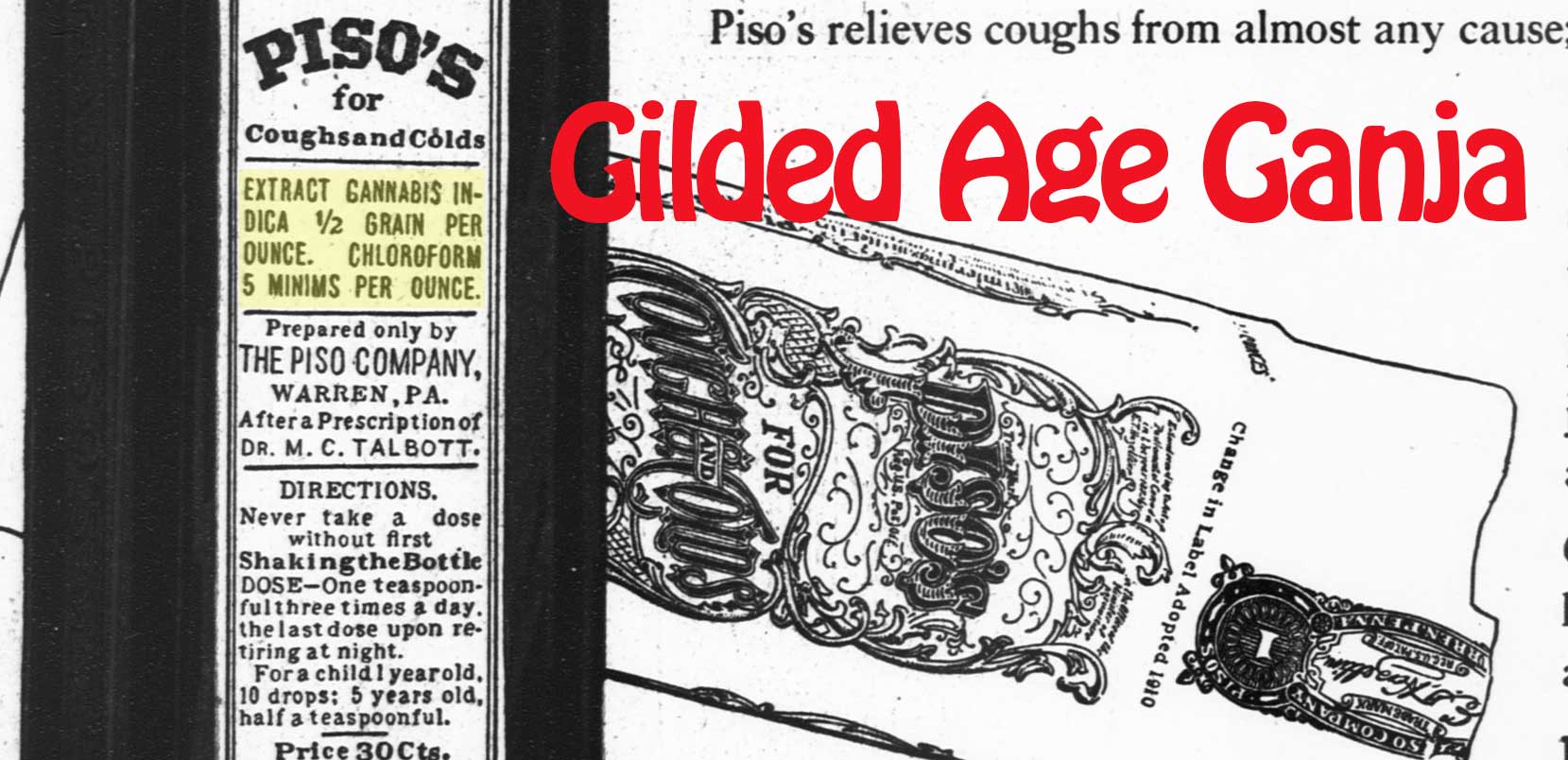

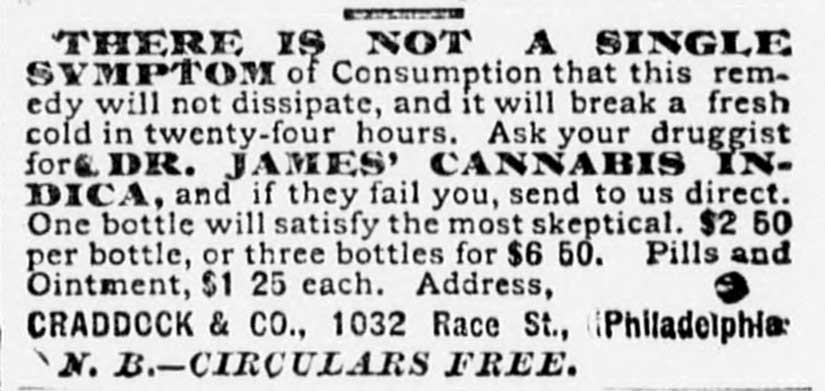

You see, in the Edwardian era, cannabis was legal. That is what they called it, too: cannabis. Or, if one wanted to be a little more flash: Indian hemp, ganja, or (in a more potent preparation) hashish. One of the most popular Edwardian uses for cannabis was as a foot soak for corns. But it was also sold as a cure for consumption, bronchitis, asthma, veterinary indigestion, and simple coughs. It was not until 1906 that over-the-counter products had to declare any cannabis on their labels, but before then any number of “remedies” could have given a nice tipple.

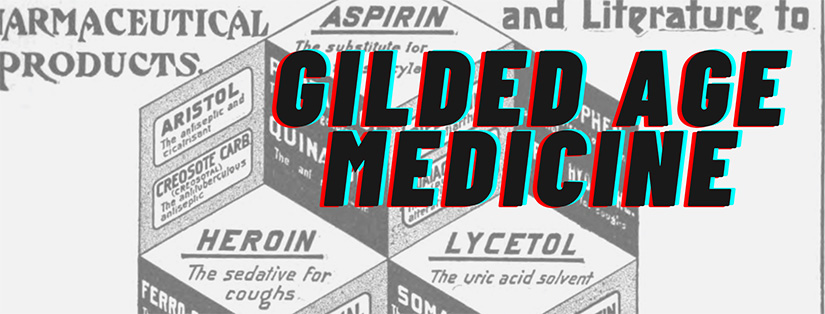

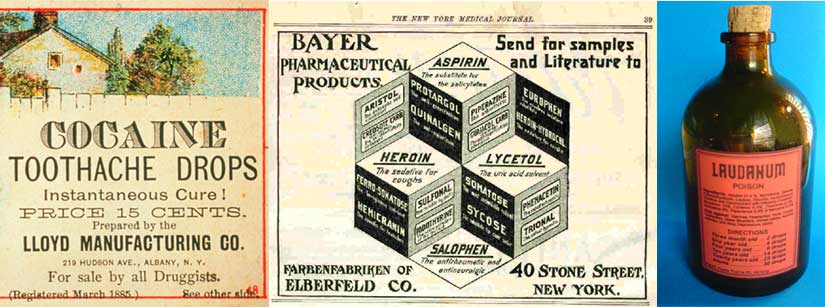

Keep in mind that this was also the era when cocaine was sold for toothaches, heroin was advertised in medical journals, and tincture of opium (laudanum) was packed in doses for infants. So, there was that.

At this point, cannabis customers considered themselves more “cosmopolitan” than the average drug user. Some men believed cannabis to be a female aphrodisiac: “It is just the thing to rouse the wild demimondaine instinct that lurks in the back of the heads of some romantic girls.” A more broadminded pot philosopher said: “It has been contended by an astute philosopher that true happiness will only be possible when time and space are abolished. Well, this is what hashish temporarily accomplishes.”

Hemp had its partisans, too. At the turn of the twentieth century, there was a worldwide shortage of naval cordage. When the United States took the Philippines as a colony, they found a local substitute: abaca, or Manila hemp. This is an entirely different species—a type of banana plant, actually—but its fibers were similar to cannabis sativa. This was the only export of the Philippines that the American colonial government allowed to be freely traded, as long as it was sold only to the States. (Later, during World War II, another hemp shortage so threatened the naval war effort that the government handed out seeds and gave draft deferments for farmers willing to grow it. They even made a film called “Hemp for Victory.”) The problem for Mr. Hemp, though, was that his cousin ruined the party, at least in the United States.

If everyone was so happy with their cannabis—both plants—in the Edwardian era, what happened? The 1910 Mexican Revolution! Um, what? No, really. The unrest south of the border sent large numbers of refugees into the United States. Cue the xenophobic backlash. What better evidence of the insidious social ills brought by these new immigrants than a dangerous new drug that turned American children into imbeciles?

That is when the name of the intoxicant changed. It was no longer cannabis, or Indian hemp, or ganja. It was marijuana—an Anglicization of the Latin American term marihuana, which itself came from either Chinese immigrants, Angolan slaves, or just a spontaneous combination of Maria and Juana. We don’t really know. The point was to portray the drug as something new, something wicked, something “loco” that would cause “incurable insanity.” The delivery system used by Mexicans—smoking—was evidence of this distinction.

One newspaper account said:

After three or four puffs the beginner’s mind becomes confused. There is, at first, a harmless sort of mental exhilaration. All the worries and sordidness in the user’s life fade away. He finds himself floating through space as if on a cloud and doing everything, in fancy, that he ever wanted to do….Then comes a period in which hallucinations dominate the addict. Motive-less merriment or maudlin emotion usually follows, after which a pugnacious attitude ensues.

Pugnacious? Yep. Others agreed. They said that marijuana was “more ruinous in its effects than cocaine, heroin, opium, morphine, or any of the others.” Another suggests curing a marijuana addiction with cocaine, which he believes is less habit-forming. It may be true that the drug then was not the same as the drug today, but racism was also a factor, at least in the late 1910s and the 1920s. The irony is that Mexico banned marijuana in 1920—17 years before the United States—and yet Americans still blamed the “infection” on them. For example, a Mohave County sheriff wrote up a public account of a run-in he had with a “bad Mexican,” a man appropriately named Marijuana for the substance that he sold. This kind of tale filled the papers.

But the anti-marijuana movement really gained traction in the Great Depression. This may be because this is when the drug became more popular with white Americans, or it may be because of the breakdown in social norms that came with high unemployment and population dispersal. And then a movie called Reefer Madness hit the screens in 1936. In the movie, a group of young smokers see their enjoyable evening go from casual fun to promiscuous sex to crushing depression to suicide. Within a year, the Marijuana Tax Act was passed, “restricting possession of the drug to individuals who paid an excise tax for certain authorized medical and industrial uses” (PBS).

That’s not the same thing as totally illegal, right? It took the conservative backlash of the 1970s and 1980s to do that. But maybe we have come full circle to the Summer of Love—or, as the case may be, to the Winter of Love. But, who knows? Pot is still illegal under federal law, and though the Obama administration adopted a policy of noninterference with the states in 2013, President-Elect Donald Trump might not feel the same way. As a boarding school teacher in Massachusetts, I am not terribly excited about the idea of patrolling dorms in a pot-accessible state. But maybe I will buy some for my mother for her corns…

(Featured image is an ad for Pico’s cough remedy, courtesy of the Library of Congress.)