The historical backdrop of my books is the Spanish-American War of 1898, when the United States acquired the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam for $20 million.

American readers, how long did you study this period in your high school history classes? Maybe a day? A half a day? This complex series of wars have been getting more attention recently but not nearly as much as they deserve. Frankly, everything Americans know about their country’s role in the world stems from this tipping point. Whether you agree with it or not, American “exceptionalism”—the idea that America’s democratic history, transparent legal system, and free market economy make it especially suited to transform the world for good—was born here.

Before 1898, America’s overseas interventions were relatively minor. The US intervened in Chile, Brazil, and Nicaragua in the 1890s; and, admittedly, we almost got in a tussle with Britain over Venezuela, but that was settled by appointed commissioners (none of whom were actually Venezuelans). There was also a scramble for guano islands in the Pacific. Check out How to Hide an Empire by Daniel Immerwahr.

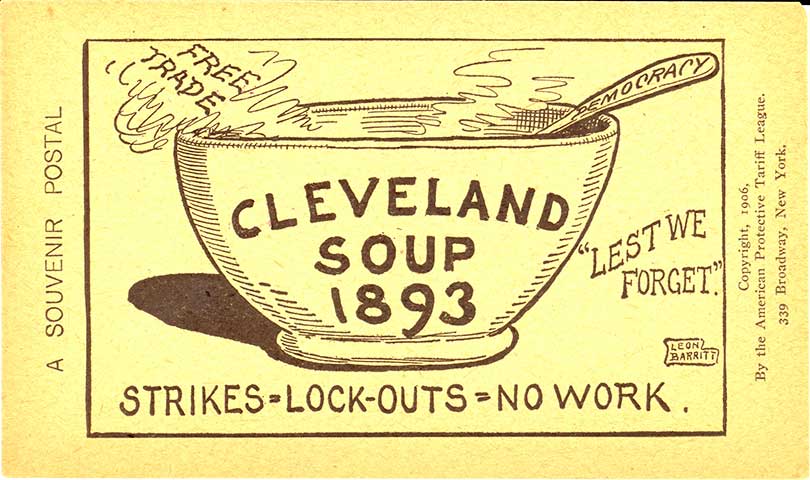

Still, most Americans had not yet developed an appetite for extensive land conquest in Asia, as a group of American planters and US Marines found out when they overthrew the legal monarchy of Hawaii in 1893. They wanted the US to annex the islands, but President Grover Cleveland, an anti-imperialist, refused. At that time, the mood of the public was: “What are you boneheads doing? Why do we want Hawaiian problems when we have problems galore here on Main Street?” I’m paraphrasing.

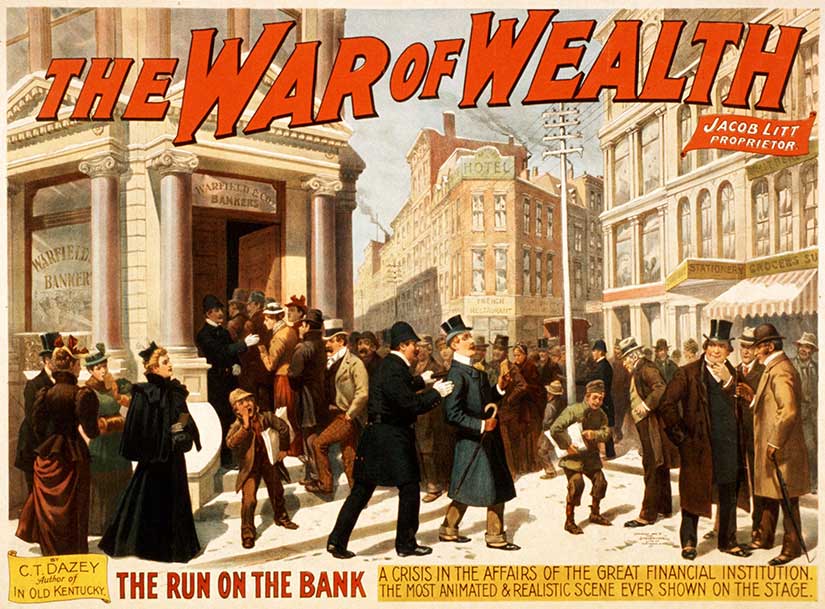

So Hawaii went into limbo. More on them later. And then a depression hit in 1893—a big one. In fact, it was the worst American economic crisis to date (in a time of peace), and remains one of the worst in American history. And that was when everything changed.

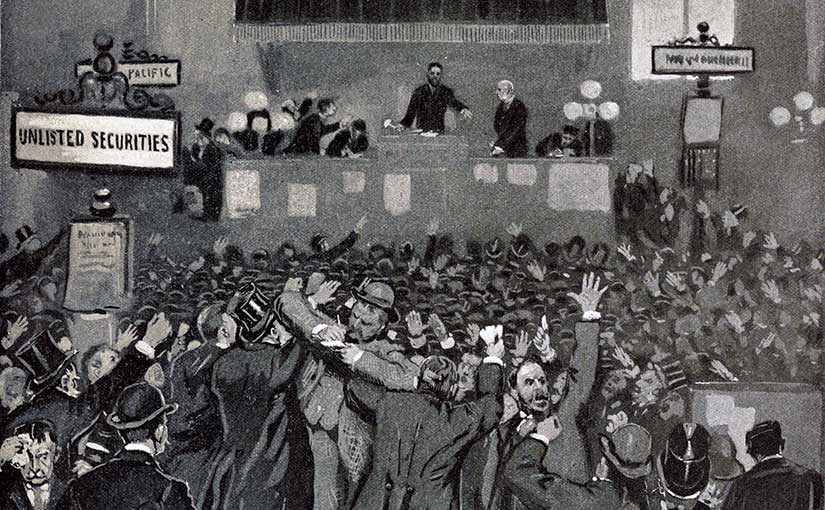

The cause of the panic was, ironically, progress. Railroads turned a patchwork of small agricultural markets into a single large one. That plus mechanization and improved farming techniques drove down prices and put small farmers out of business—or in terrible debt, which led to a debate over abandoning the gold standard. Though manufacturing blossomed in the cities, conditions were appalling. Professional strikebreakers, including private security firms like the Pinkertons, ensured that labor disputes were violent on all sides. Without collective action, wages stayed low, and that meant there were not enough customers to buy all the stuff the country produced.

What was the answer? People began to think: “If we can’t sell our goods here, let’s hawk them abroad, like the Europeans do! We should be able to sell to China, too. Commodore Perry already ‘opened’ Japan for everybody. Oh, and by the way, you’re welcome!” I’m paraphrasing again.

Americans began to get hungry for empire—but should that empire be an economic or a territorial one? Men like Frederick Jackson Turner bemoaned the closing of the American frontier in 1890. He said the expansion across the West was where Americans had grown strong and manly. The virtually unlimited forests and plains available for the taking—as he saw it—had ensured that America would never become a feudal society dominated by a small class of land-owning nobles. And now that Americans had settled everything from New York to San Francisco, where would we go?

By the way, Turner was not concerned about people of color who were destined to be the losers in his vision. He was not concerned about their lives, their rights, their culture, or their children. Systemic discrimination based upon race and ethnicity was an unspoken platform of the Gilded Age from the beginning. Reconstruction was over. Now the white northerners and southerners would institutionalize their advantages against everyone else, especially African-Americans. This combination of lynchings, convict leasing, disenfranchisement, and segregation is often called “slavery by another name.” Moreover, the military leaders that brought you the Indian Wars are the same ones who will bring you the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars.

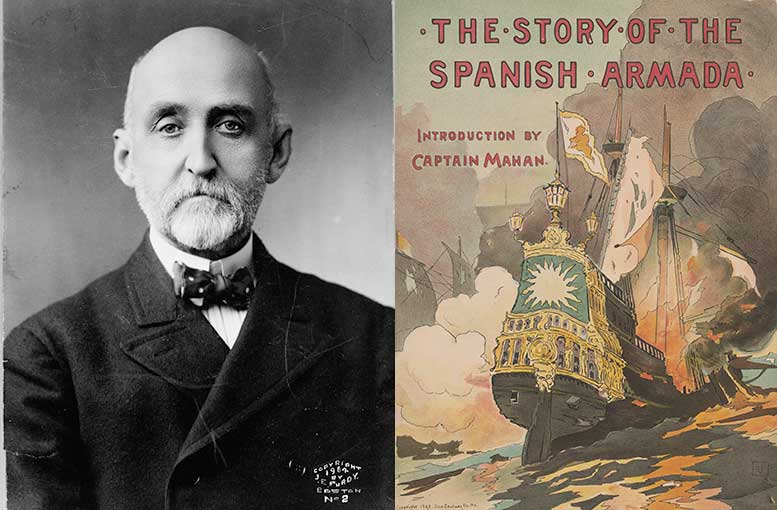

One influential group of strategists emphasized reach, not largesse. The US needed ports, they said, lots and lots of them around both oceans. Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, a professor at the Naval War College, thought it imperative that America protect its sea lanes with a strong navy, which would be “the arm of offensive power.” To do that, America needed coaling stations all around the Caribbean and Pacific, à la the Portuguese maritime empire. Mahan particularly insisted that “no foreign state should henceforth acquire a coaling position within three thousand miles of San Francisco.” (By the way, coal would still be king for another twenty years or so. And the oil era will not change our priorities, merely the pins in the map.)

Mahan inspired a whole generation of imperialists. A prominent young lawyer in Indiana named Alfred J. Beveridge articulated this group’s position so cogently that his oratory alone propelled him to a seat in the United States Senate:

American factories are making more than the American people can use; American soil is producing more than they can consume. Fate has written our policy for us; the trade of the world must and shall be ours. And we will get it as our mother [England] has told us how. We will establish trading-posts throughout the world as distributing-points for American products. We will cover the ocean with our merchant marine. We will build a navy to the measure of our greatness. Great colonies governing themselves, flying our flag and trading with us, will grow about our posts of trade. Our institutions will follow our flag on the wings of our commerce. And American law, American order, American civilization, and the American flag will plant themselves on shores hitherto bloody and benighted, but by those agencies of God henceforth to be made beautiful and bright.

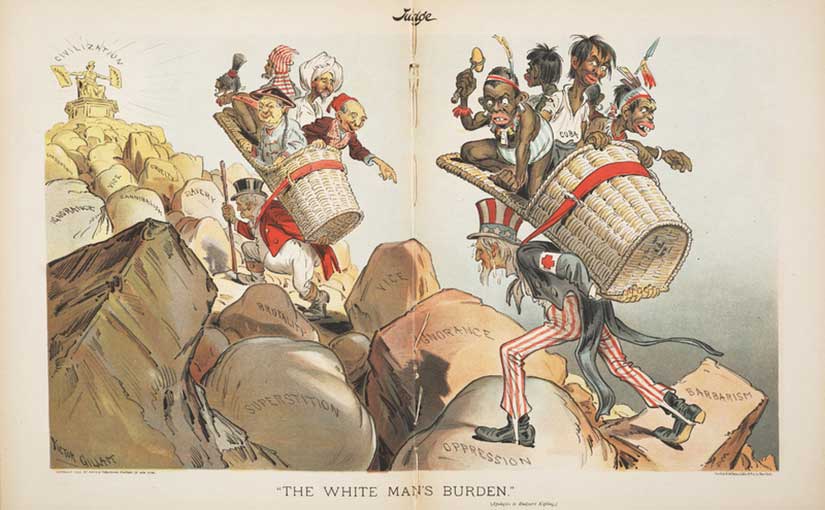

Note that Beveridge believed in the full colonial system, with all the rights and responsibilities that entailed. He was eager to take up Rudyard Kipling’s call to the “The White Man’s Burden”: “To wait in heavy harness, on fluttered folk and wild—your new-caught, sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child.” Though Kipling and Beveridge were born three years and a hemisphere apart, they were kindred spirits.

Theodore Roosevelt said that it was time to “have done with childish days,” time to “search your manhood,” in Kipling’s words. Roosevelt wanted conquest, even if it meant war. Maybe especially if it meant war. He said:

We do not admire the man of timid peace…Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in the gray twilight that knows not victory nor defeat.

He saw no danger of “an over-development of warlike spirit.” In fact, just the opposite. He worried most about becoming “a wealthy nation, slothful, timid, or unwieldy.” We remember Teddy Roosevelt best for his adage to “speak softly, and carry a big stick,” but I see little evidence of soft speaking in his public record. This quote of his is far more representative: “Peace is a goddess only when she comes with sword girt on thigh.”

Roosevelt was hungry for war, and he was not alone. But where? Against whom? And how would he rally an isolationist public recovering from depression and bring them all the way to war? Enter Spain, stumbling awkwardly into the room.

Continue reading Part 2 here.

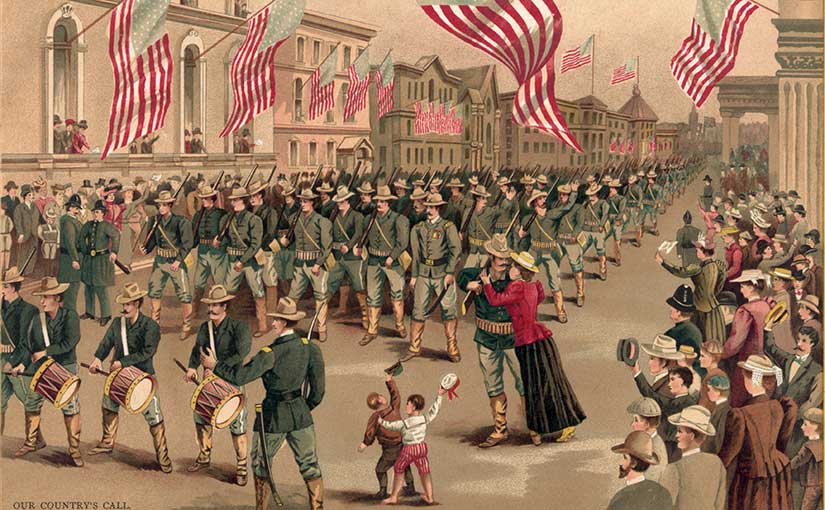

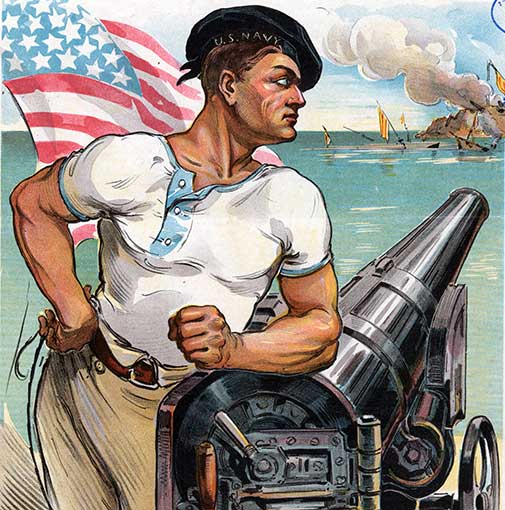

(The featured image is from an 1898 patriotic poster, found at the Library of Congress.)