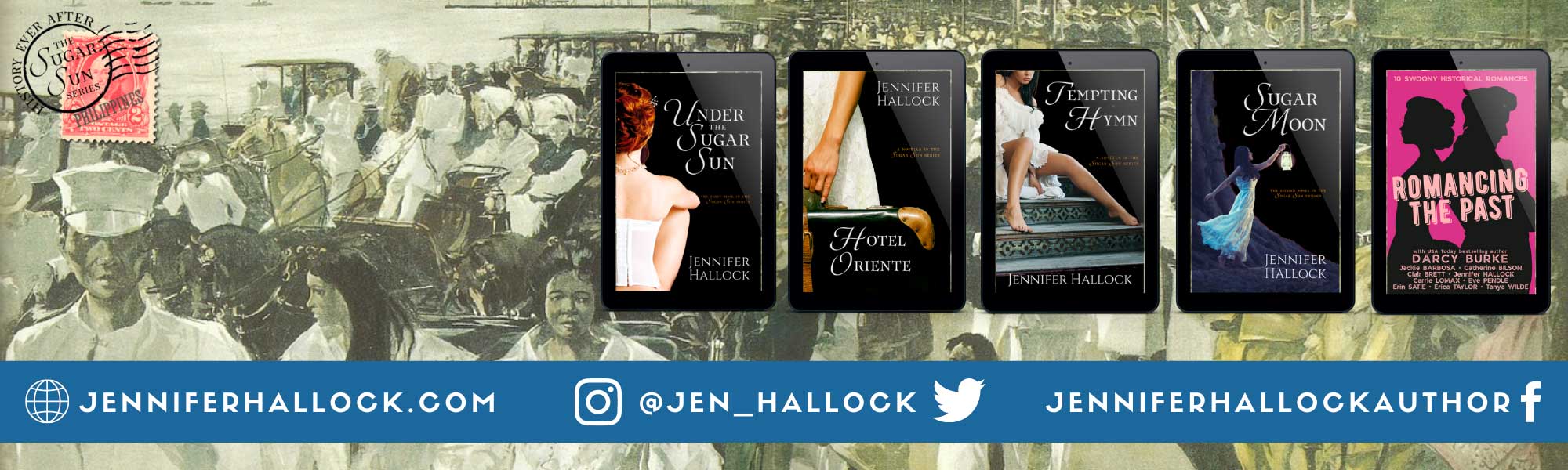

I am excited to announce that the Hotel Oriente is open after a pretty thorough remodel: better pacing, more hotel tidbits, and—best of all—brunch!

BUT WAIT! If you have not read Hotel Oriente yet, I have an amazing deal for you. You can grab it and nine more books in the Romancing the Past anthology for almost nothing. Yes, all ten swoony romances for the low price of 99¢ until September 15th, and only $4.99 after that.

More from the Author’s Note of the 2021 Revision of Hotel Oriente:

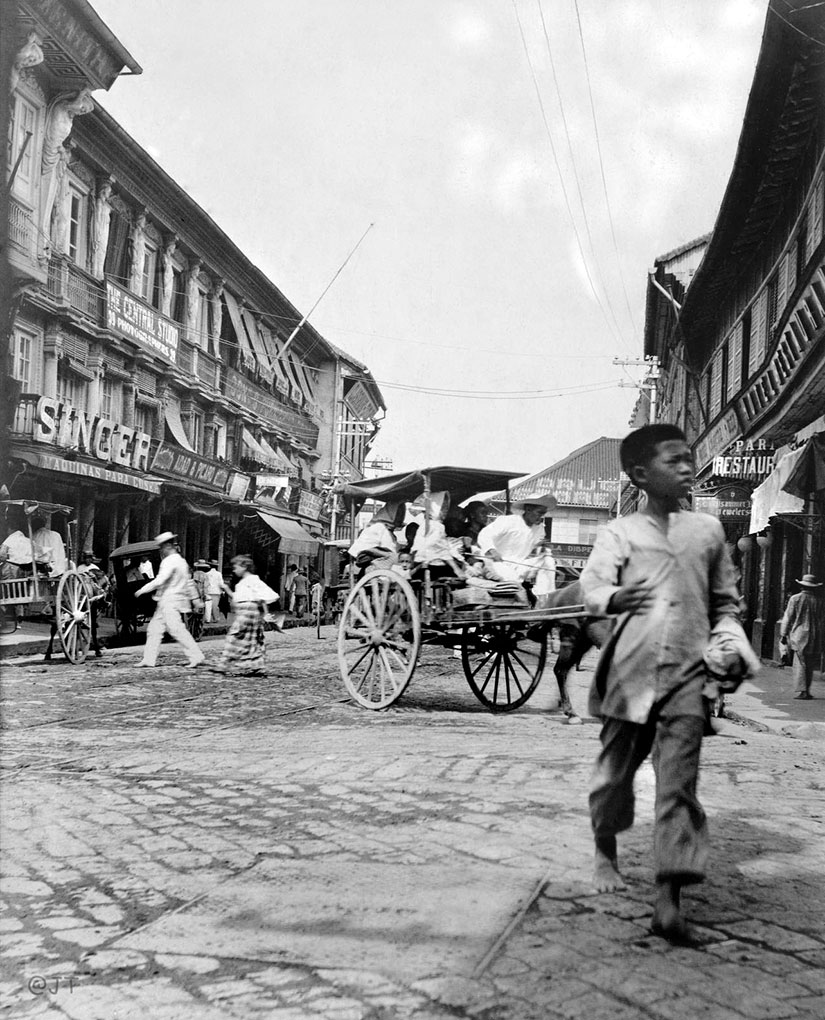

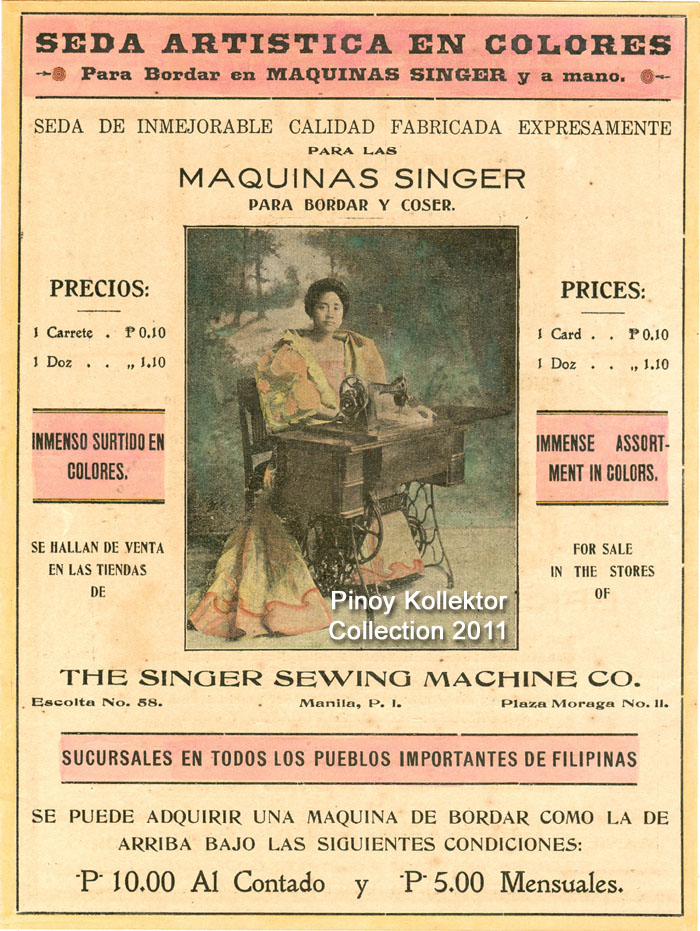

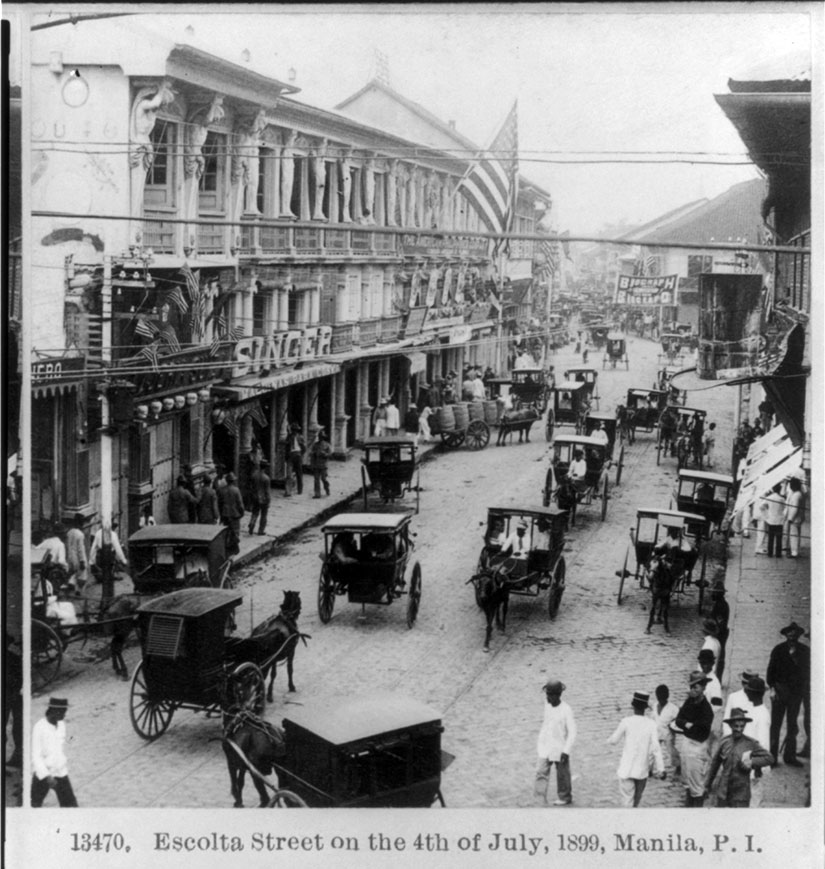

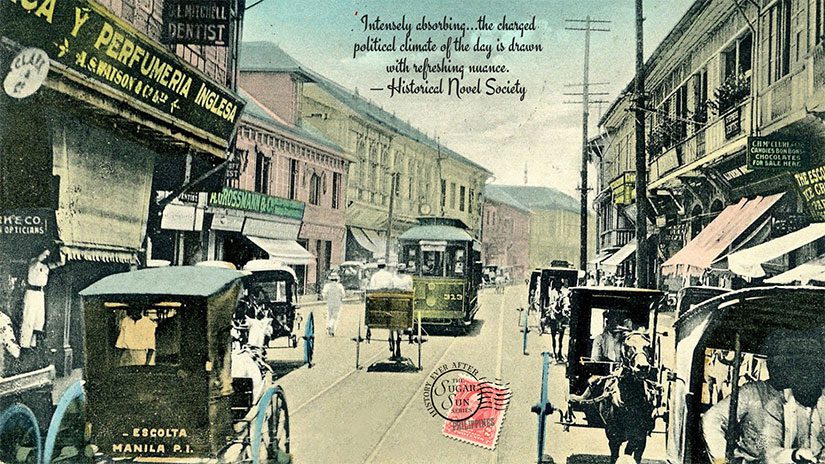

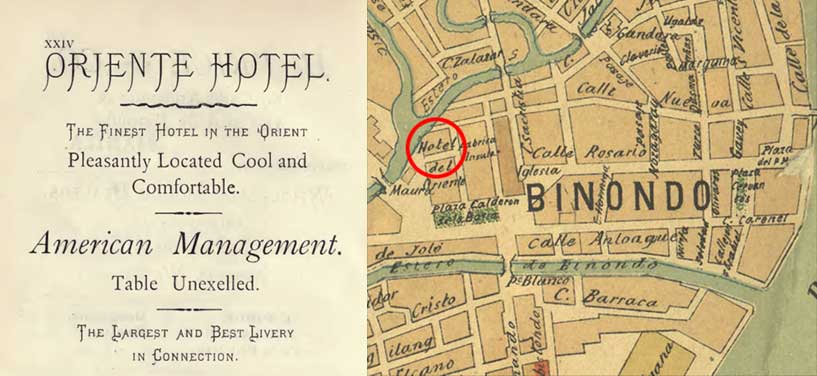

Let’s dig into the history. Yes, the Hotel de Oriente did exist, though it was known by many spellings. Hotel de Oriente was the name plastered across the exterior molding, but I found all the following used: Hotel Oriente, Hotel d’Oriente, Hotel el Oriente, Hotel Orient, and every one of these in reverse order. It was the place to stay until the Insular Government purchased it in November 1903 to use as the headquarters of the Philippine Constabulary.

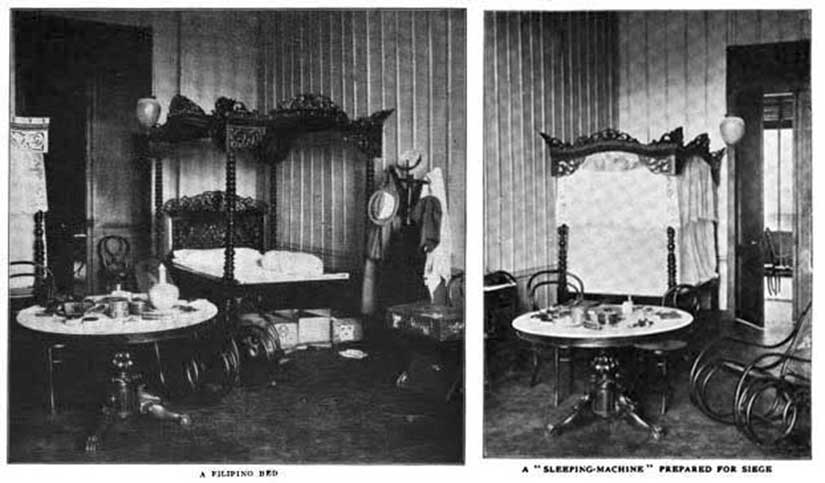

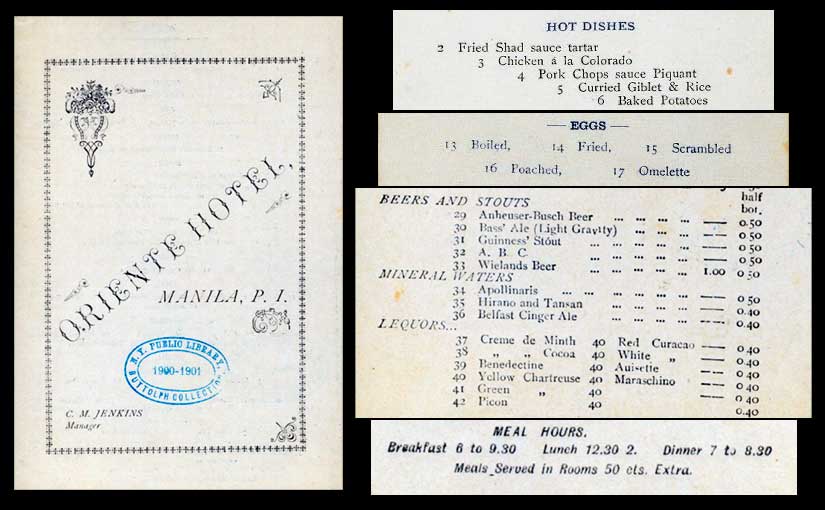

Many photos exist of the exterior of the building, and Las Casas Filipinas de Acuzar has even built a working reconstruction and conference center in Bataan, which I have visited. Other than a few room photos, though, the interior is known only from traveler’s reports, including those on Lou Gopal’s Manila Nostalgia blog, as well as a variety of journals in the public domain. From these, I borrowed the complaints over “missing” mattresses and excessive egg dishes. I borrowed the bathtub incident from my father-in-law, who managed an American military hotel in Bangkok during the late 1960s.

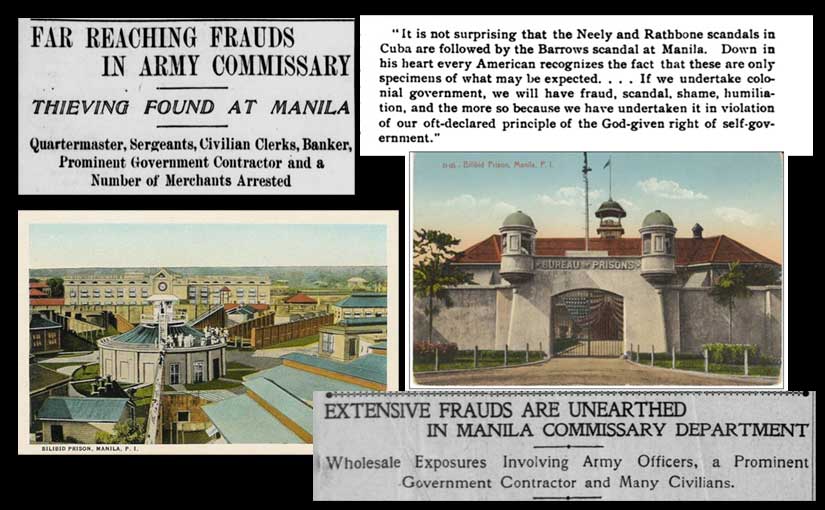

A real assistant manager of the Oriente was implicated in the true scandal that almost engulfed Moss and Seb. Captain Frederick J. Barrows, the actual quartermaster of Southern Luzon, stole one hundred grand a month for almost a full year, pocketing nearly $1.2 million by 1901 (the equivalent of $38 million in 2020). This was nowhere near the largest war profiteering in world history—that honor goes to reconstruction contracts during the Iraq War—but it is still a lot of money. A court-martial sentenced Barrows to five years in Bilibid Prison, and that may have been getting off easy. He had a better chance at a fair trial inside the military than out of it. This was true for all civilians, Filipino or American. The Insular Cases, a series of 1901 decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court, were the true legal architecture of empire, and they said that the Constitution did not follow the flag. I pushed forward the date of these decisions for my story, but only by a few months.

Much of Della’s article on the scandal is reproduced from the Los Angeles Herald’s April 1st issue, no joke. Please consider this acknowledgment my endnote for “Far Reaching Frauds in Army Commissary,” from page one. I used as much of the original wording as I could because I wanted Della’s writing to match the standards of the profession in 1901. The previous edition of this novella did not do a good job of displaying her talents as a journalist.

Della’s story was inspired by a deaf voyager, memoirist, and teacher named Annabelle Kent. While I was researching Under the Sugar Sun, I found a terrific description of a steamer’s rough entrance into Manila Bay. Kent’s Round the World in Silence proved her to be a thrill-seeking woman impervious to seasickness. (According to later U.S. Navy experiments, those with a damaged vestibular system are less likely to suffer from the bucking motion of the waves.) She circumnavigated the globe, mostly with strangers who did not speak American Sign Language. To me, Kent had the perfect spirit to infuse a romance heroine.

People say to “write what you know,” which is excellent advice—but plot bunnies lead me down precarious burrows. Could a deaf writer have better written about Della Berget? No doubt. Are there better books out there about Deaf Culture? Every single one written by someone who identifies as hard of hearing to profoundly Deaf. But I took a risk and wrote Della as best I could. This meant research: the Limping Chicken blog and the Gallaudet University archives were especially helpful. Of course, all mistakes or errors are entirely mine. At the time, the U.S. Congress required Gallaudet to teach only the “Oral Method” of communication, which is why she speechreads instead of speaking ASL. Della does not yet know other deaf people in her corner of Manila—she is new to the city—so there is not enough treatment of Deaf Culture and its rewards in this story, nor would I be the best person to translate such ideas to the page.

Moss is also loosely based on an actual person: West G. Smith, the American manager who ran the hotel for Ah Gong, proprietor. West Smith became Moss North? His wife Stella became Della? Yes, I amuse myself. Smith arrived with the Thirteenth Minnesota Volunteers and stayed to manage the Oriente, but the rest of Moss’s personal history was entirely fiction. Also, I liked the name and story behind the White Elephant resort in Nantucket, but it has no relation to Moss’s uncle’s hotel, which was instead based on the Windsor in St. Paul.

Hughes Holt’s background was a fictionalized conflation of the two West Virginian congressmen of the era, but his personality hews closer to Senator Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana, an orator who built a career on the embrace of overseas expansion. Beveridge did visit the Philippines—albeit two years earlier, in May of 1899—so that he could “understand the situation” (his words) before assuming his seat in the Senate. Unlike Holt, Beveridge impressed local soldiers with his physical endurance and ability to withstand deprivation. Like Holt, he left the islands more imperialist than ever. Emboldened, the U.S. Army would wage a relentless war, and so would privateers. The anecdote about violent American outlaws in Pampanga was ripped from page six of the 15 May 1901 issue of the New York Times.

Though Moss’s anti-imperialist attitudes were rare among soldiers, his concerns can be found in archived letters, newspapers, and Senate testimony. It was Major General Smedley Butler, USMC—two-time recipient of the Medal of Honor and veteran of the Philippine-American War—who wrote War is a Racket in 1935. He claimed that his three-plus decades of service had been “conducted for the benefit of the very few [commercial and oil interests], at the expense of the very many.”

It did not take as long for others to see the light. Soldiers of African American regiments related the injustice of imperialism with contemporary clarity. Sergeant Major John W. Calloway of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry was persecuted views he expressed only in private correspondence. Calloway was especially close to Filipino physician Torderica Santos, much like Moss was best friends with the fictional Judge Eusebio Lopa (inspired by the real Lieutenant Salvador G. Lara). Calloway also made his life in the Philippines after the war, marrying and raising fourteen children.

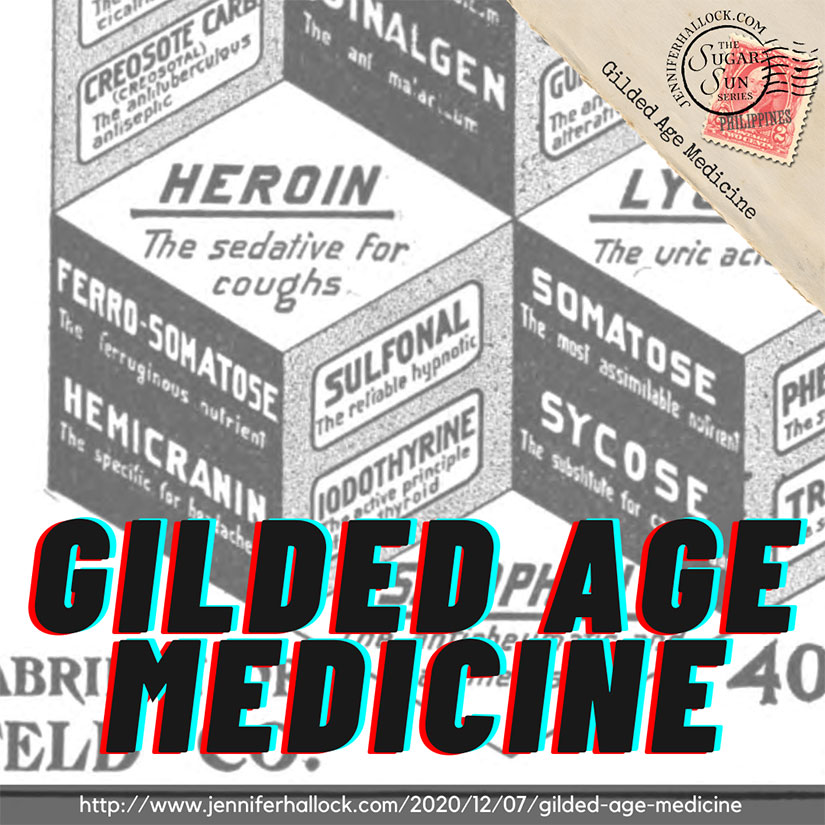

That brings me to Moss’s use of a condom, which was based on the state of contraception at the turn of the twentieth century. I do not know how hard it would have been to purchase a sheath in Manila, but it may have been easier there than in the United States. The 1873 Comstock Act had made it illegal to distribute birth control or information about birth control through the mail or across state lines, not imperial ones. Yes, the Philippines was a majority Catholic country, but papal pronouncements did not ban “artificial contraception” until 1930. Did Della understand what the condom was? It was possible, given the close contact she had with married friends at her university. Also, hearing people tended to be indiscreet around her, often to their own detriment.

Thanks for getting this far. Remember that your honest review helps readers find books they love. If you have taken the time to rate and review on Goodreads or the retailer of your choice, thank you. For everyone, I hope you enjoyed Moss and Della’s story. Here’s wishing you a History Ever After!