Quartermaster is a military word, and therefore it may be as unfamiliar to you (or more so) than the other phrases in this glossary. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term comes from the Middle Dutch word quartiermeester, the naval officer responsible for organizing the watches. This duty was expanded to include all provisioning—from rations to ammunition, from rifles to haversacks, and from ships to horses.

Today, military logistics is more important than ever. The US Armed Forces recruits men and women with engineering and business degrees to keep the soldiers, sailors, aviators, and marines “marching on their stomachs.” But during the Philippine-American War, it seems that anybody could get a job in the quartermaster depot. Why were they so desperate?

Today, military logistics is more important than ever. The US Armed Forces recruits men and women with engineering and business degrees to keep the soldiers, sailors, aviators, and marines “marching on their stomachs.” But during the Philippine-American War, it seems that anybody could get a job in the quartermaster depot. Why were they so desperate?

After the Civil War, the United States Army had shrunk to a size smaller than today’s New York City Police Department. Think about that for a minute. Yes, there were small military interventions in Mexico, Korea, and Samoa, in addition to a series of conflicts known as the Indian Wars, designed to consolidate Federal control over the rest of North America. But at the time Americans feared they would lose their liberty to a large standing army, so the military remained small despite it all.

When the Spanish-American War began, Congress found itself in a bind. At first they relied upon volunteer units from each of the states, but those enlistments were only a year long. When the Cuban conflict turned into a protracted war in the Philippines, Congress doubled the size of the regular Army once, then twice. For the first time, the US sent a large force to Asia—up to 69,000 at a time—to fight its first overseas war of occupation.

This huge force needed to be fed and armed. If you could read and write, you might be able to swing a job “in the rear with the gear,” rather than wading through rivers and rice paddies under fire. And, if you had an entrepreneurial spirit, a golden opportunity beckoned: crates and crates of goods came in, and who was to say if a few hundred pounds here or there was “lost”?*

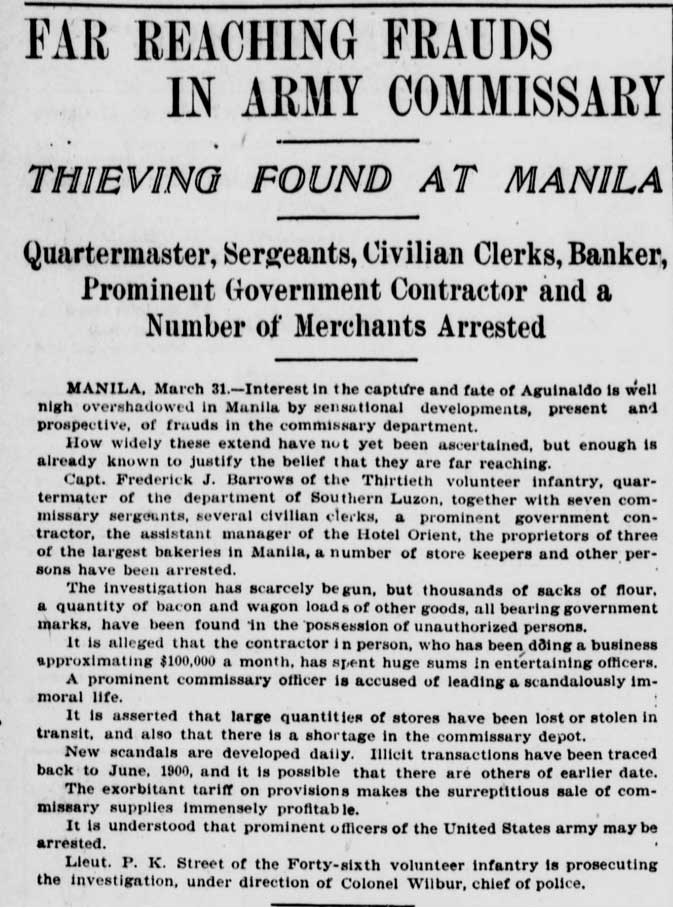

One of these “entrepreneurs” was Captain Frederick J. Barrows, who was found to have been embezzling $100,000 a month—the equivalent of $2.9 million in today’s terms—in flour, bacon, and other staples. He then sold the goods to local hotels, bakeries, and restaurants.

Barrows got away with this scheme for almost a year. In sum, he and his accomplices probably made (and spent) about $24 million in 2015 dollars. Even now, that goes a looooong way. As the article says, Barrows used his ill-gotten gains to lead “a scandalously immoral life…entertaining officers,” which means he was throwing big parties with lots of prostitutes. It’s good to be the quartermaster.

But, be careful: if you steal while you’re in the Army, and steal from the Army, you get punished according to Army regulations—in this case, five years imprisonment in Bilibid Prison in Manila, which might have been worse than Leavenworth. The Spanish built Bilibid but never imprisoned their own citizens inside, which is never a good combination. Don’t let the quaint postcard below fool you.

So you see, the scandal I used in Hotel Oriente was a real one. But my hero, Moss North, managed to avoid the dragnet. How? Read the book and find out. It’s available free on Kindle Unlimited or for purchase at only $0.99.

* In the “history repeats itself” column, the US sent plastic-wrapped crates of cash—$12 billion dollars worth—to Baghdad in 2004, and about half of that seemed to disappear. It was called “the largest theft of funds in national history.” But don’t worry—the Department of Defense finally accounted for the funds in 2011, which to some was 7 years too late.