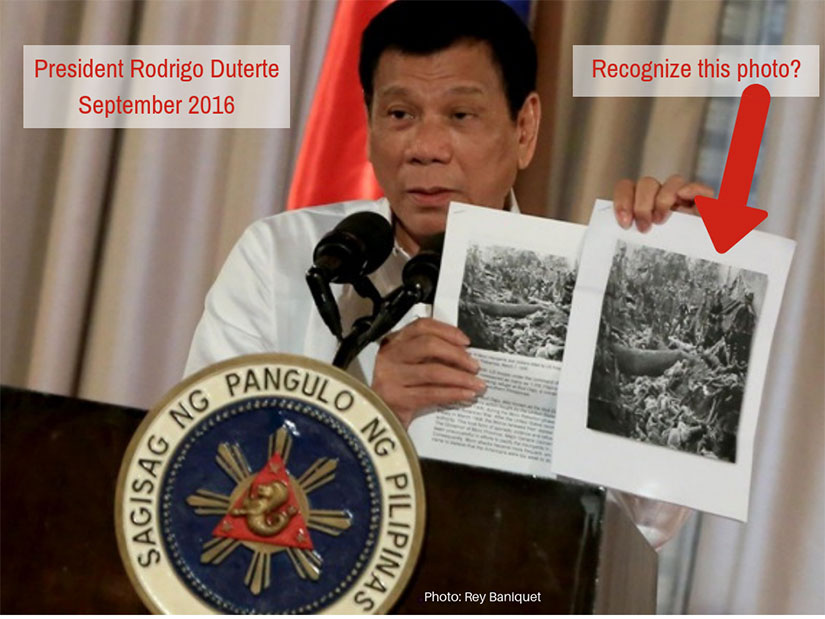

What a week for the Philippine-American War in the news! Last October, I wrote a post entitled, “Why a War You’ve Never Heard of Matters More than Ever.” Back then I argued that the Philippine-American War defined the American century, but now I see that it might be redefining the next century, too. Whose century will this one be? I leave that to you.

The war has gotten a lot of attention this week—or maybe notoriety is a better word. If you need to catch up with (1) how this war started; (2) how it grew to include the Philippines; and (3) how the Americans ruled, check out this page of history posts from the website.

But let’s get to this week, shall we?

Pershing and the Moros:

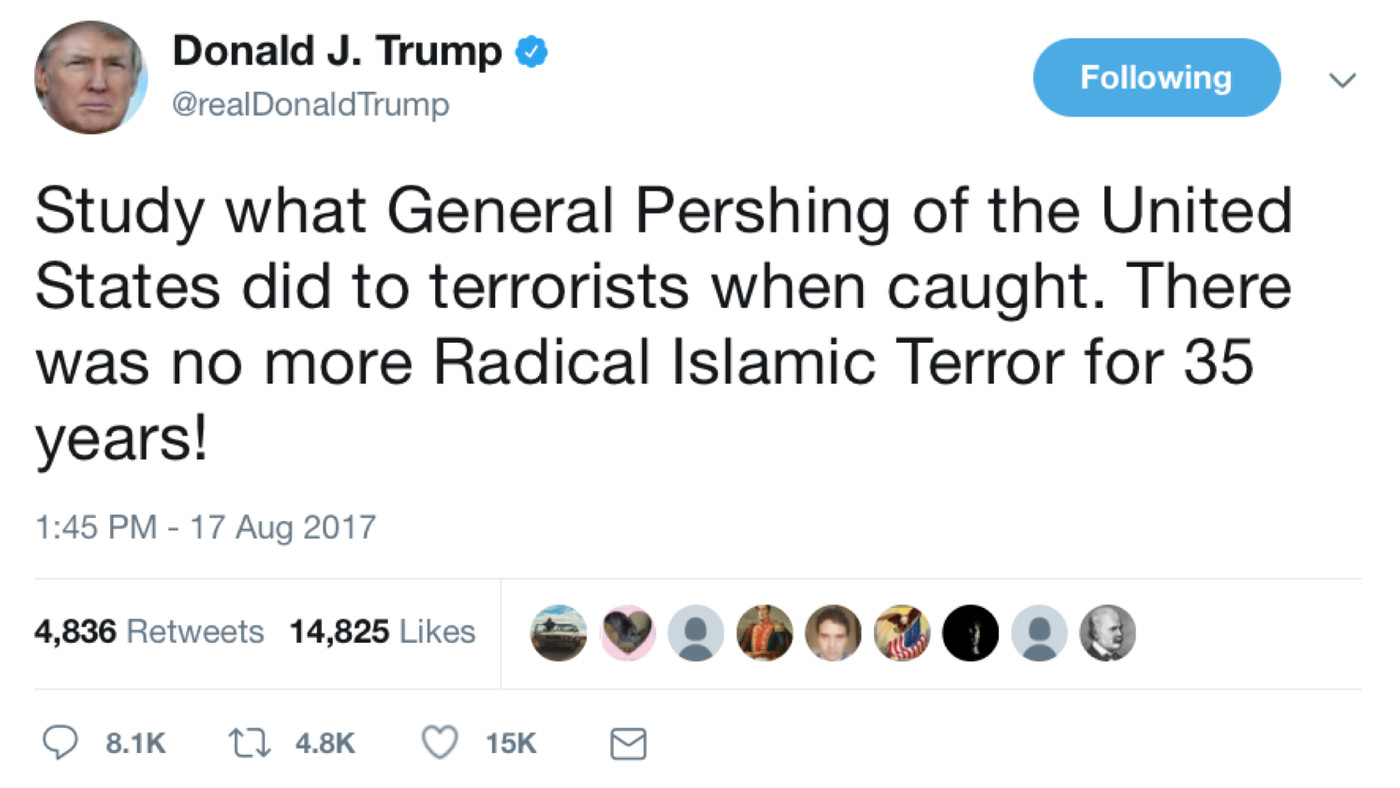

It started with this tweet:

This old chestnut, again? My job is not politics, but when politics tries to leverage Philippine-American War history, it’s game on! What President Trump is referring to is his (false) claim that General Pershing used bullets dipped in pig’s blood to pacify the Moros of the southern Philippines. Not true. This myth has been debunked many, many times.

First of all, the Moros were not terrorists:

In the first decades of the 20th century, Muslim Filipinos weren’t targeting American cities or kidnapping tourists. They were attacking American soldiers for one simple reason: The United States had invaded and was occupying their home.

— Jonathan M. Katz in the Atlantic

Therefore, Pershing was carrying out imperial policy, not an Islamophobic agenda. (Not that imperialism isn’t problematic, but you have to remember that it was the official policy of the US government after the 1898 Treaty of Paris, when the Americans bought the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam for $20 million and decided to keep them as “insular possessions.”)

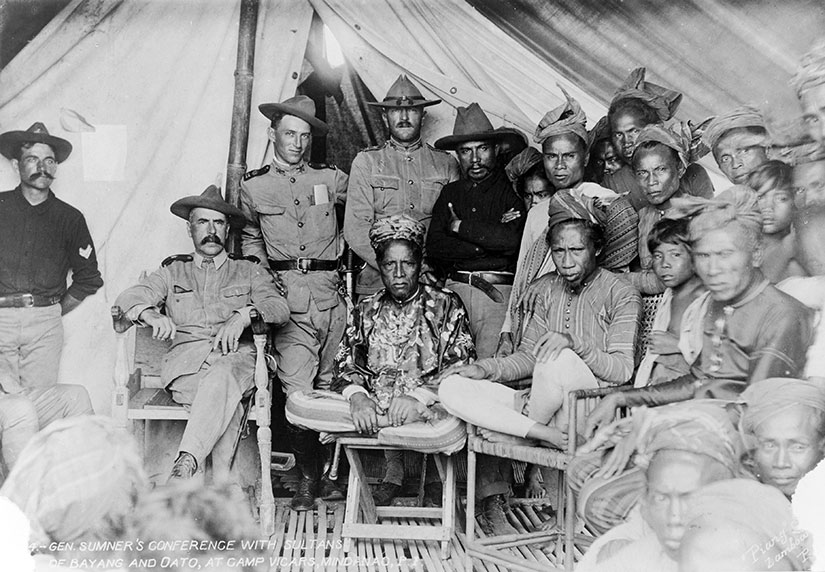

The Moros wanted assurances that the Americans would not try to change their culture or religion; Pershing wanted assurances that the Moros would not challenge US rule. This compact was not as easy as it sounds. One of the cultural practices the Moros wanted to defend was slavery. What would you do? The Americans had already quelled resistance in the rest of the islands, so they decided they could not let slavery stand. And they wanted the Moros to pay taxes, of course. This is where Pershing came in, but his attitude was not what Trump suggests.

In 1911, Pershing suggested that the Moros use the Qur’an as a guide for their behavior. He even gave a Qur’an as a gift to one of the leaders, documents show. And that’s not all:

[Pershing] studied their language to the point where, he boasted, he could take low-level meetings without an interpreter. In return, Pershing was elected a datu, a position of respect and leadership in Moro society. He was the only U.S. official to be so honored.

— Daniel Immerwahr from Slate

Now, I should be clear: Pershing did use force. A lot of it. Over 500 Moros died at the Battle of Bud Bagsak in 1913. This active siege may have included women and children, which Vic Hurley admitted was the “big problem the Americans faced.” He indicated that this was not Pershing’s preferred way to do battle.

(The more notorious massacre of Moro civilians, the Battle of Bud Dajo, happened during Pershing’s absence from the Philippine campaign, in 1906. You can blame General Leonard Wood for that one. And you can blame General Jacob Smith for the campaign to turn Samar into a “howling wilderness” in 1901-1902. The fact that Smith and Wood’s campaigns were so public—and so publicly criticized—means that Pershing would not have risked the same condemnation willingly. Nor would he have used pig blood bullets.)

Pershing did mention in his memoir that others buried Moro fighters in graves with pigs to deter them, but it was not a practice he took part in. Besides, this threat only made sense in American minds—anything done against one’s will would not result in punishment, according to the Qur’an.

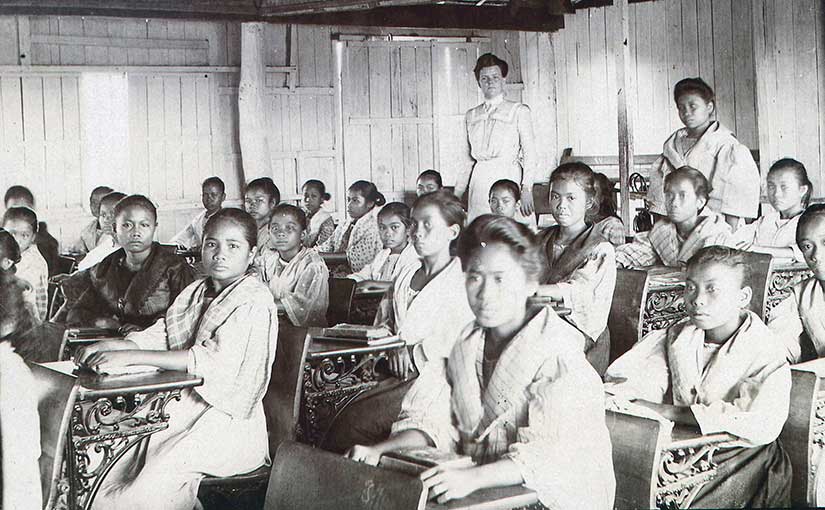

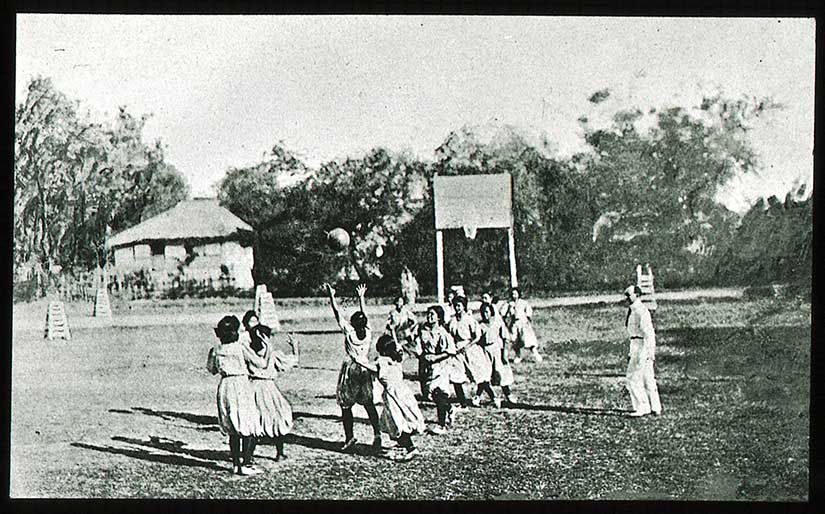

Finally, force itself was only one-half of the US military’s policy in the Philippines. If “chastisement” was the stick, “attraction” was the carrot: schools, medicine, infrastructure, limited self-governance, and so on. And then there was another piece, something surprising: forgiveness. The men who most dangerously opposed the Americans—men like Malvar (in Batangas) and Lukban (in Samar)—were granted amnesties in exchange for the surrender of their men and weapons.

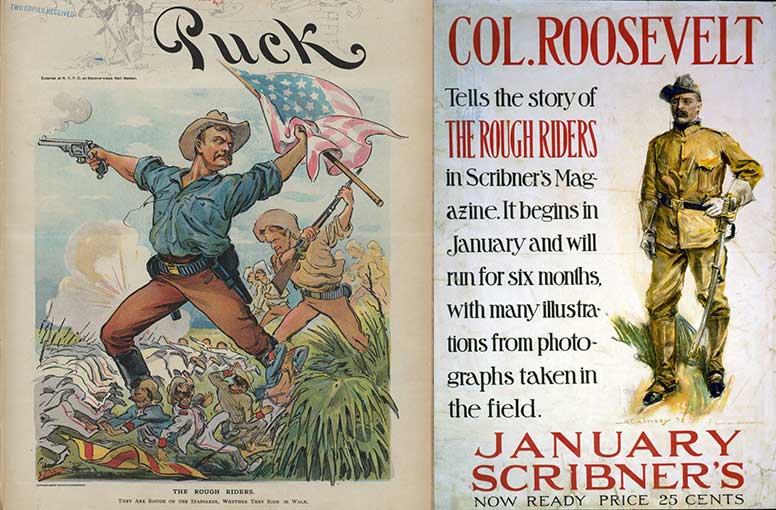

Another Roosevelt?

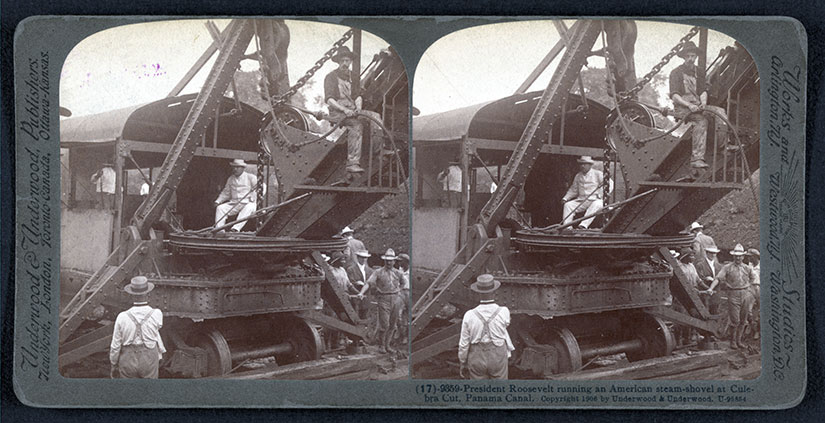

There was another misappropriation of Gilded Age history this week: Vice President Pence compared Trump to Teddy Roosevelt. Roosevelt was the one who put 230 million acres of American soil under conservation. He also first signed the Antiquities Act, which “affords the president the authority to designate national monuments—one of the most important mechanisms for conserving wilderness and wildlife habitat,” according to Field & Stream. Trump, on the other hand, directed the Interior Department to consider withdrawing protected status to 27 national monuments in order to make more room for gas and oil production. Not a great likeness there.

Pence made his comparison between Trump and Roosevelt while speaking at the opening ceremonies of the new Cocoli Locks at the Panama Canal. This brings up another contrast: Roosevelt oversaw the construction of this massive infrastructure project, but Trump’s promised infrastructure plans are falling apart after his unwillingness to condemn the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville:

The president’s much vaunted $1tn plan for American infrastructure now lies in ruins. On Thursday, he dropped plans for an advisory council on the issue, following the disbanding of two business advisory councils after an exodus of several chief executives.

There were other ways in which we could compare the two men. Both set out to change the Republican parties that elected them, but Roosevelt’s progressivism ran directly counter to Trump’s proposed tax reform for the wealthy. According to Roosevelt:

A heavy progressive tax upon a very large fortune is in no way such a tax upon thrift or industry as a like would be on a small fortune. No advantage comes either to the country as a whole or to the individuals inheriting the money by permitting the transmission in their entirety of the enormous fortunes which would be affected by such a tax; and as an incident to its function of revenue raising, such a tax would help to preserve a measurable equality of opportunity for the people of the generations growing to manhood.

Roosevelt also had a bombastic foreign policy like Trump has warmed up to, but remember this: though Roosevelt helped start the Spanish-American War (and ordered Dewey to expand the battle to Manila), he actually fought in it himself. He resigned his post, recruited his own unit (1st Volunteer Cavalry or “Rough Riders”), and shipped out to Cuba. Given how many physical ailments Teddy Roosevelt overcame early in his life, if he’d had “heel spurs,” he would not have told a single person about it.

Conclusion:

I am glad to see attention given to the Philippine-American War and the Gilded Age in general, but none of the claims by Trump or Pence stand up to the test of history.

(Featured Photo: American soldiers of the 20th Kansas in trenches in the Philippines during the insurrection. Note the open baked beans can in the left foreground. Photo from the Library of Congress.)