Taking their name from the Visayan words for “woman” and “spirit,” the babaylans were “mystical women who wielded social and spiritual power in pre-colonial Philippine society,” according to Marianita “Girlie” Villariba. I recently wrote a priestess like this named Valentina:

“We are people,” Valentina said. “Farmers, sisters, mothers. We are the faithful.”

“Fanatics,” Allegra muttered.

“Why, because we defend ourselves? You compadres are like capiz oysters, burrowing down into the sludge of occupation—first Spanish, now American. You think you will come up as shiny as a pearl. I am a healer, a shepherd. I created a sanctuary where women can be free.”

Valentina is not the heroine of the book, but she is not the villain either—no matter what the Spanish or Americans believed. Because the Spanish especially viewed these women as a threat to the spread of Catholicism and patriarchy, the friars discredited the babaylans by spreading rumors that they were really vampire-like mythical creatures, or aswangs.

But babaylans did not have to be women. You could be a man—or you could be a man living under an adopted female identity, part of the long proto-transgender tradition in Southeast Asia. (By the way, the Philippines just elected their first transgender congresswoman.) Anyone who had a lifetime’s track record of helping the community—through both bandages (healers) or swords (warriors)—could be selected. This range of duties will be important to the way the identity of babaylans will evolve, especially at the turn of the twentieth century.

The babaylan’s unique blend of nationalism and traditionalism pushed them to challenge both Americans and hacenderos at the same time. Babaylans spoke to God in their native language, and God told them to oppose the changes hitting their island. They believed that God inhabited all of nature, so the destruction of nature—particularly by industrial machines—was against the will of the universe. Men joined the movement in large numbers in the late 19th and early 20th century, particularly “discontented marginalized peasants,” according to Violeta Lopez-Gonzaga. This made the babaylans “a peasant protest movement with messianic, revivalistic, and nativistic overtones.”

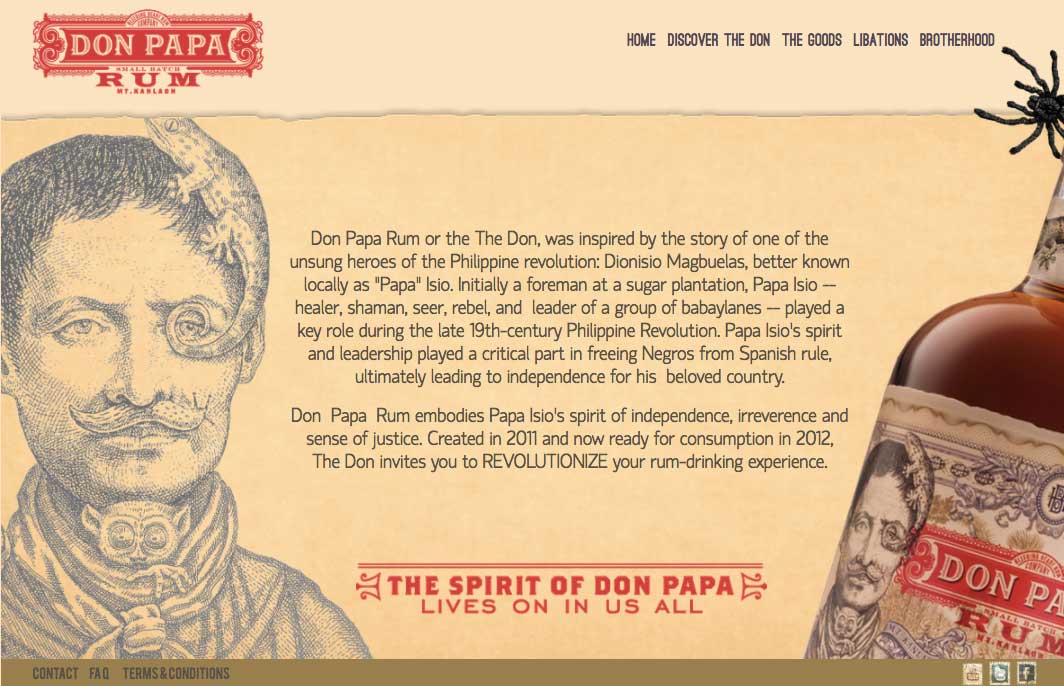

The largest of these revolts was led by Dionisio Sigobela, also known as Papa (Pope) Isio. As historian Renato Constantino wrote, the situation in the early 1900s was particularly tenuous. War and revolution had closed ports and destroyed farmland. Natural disasters like drought, locusts, and rinderpest made the situation worse. Laborers were rapidly being replaced by machines, though both were in short supply. According to Constantino, only one-fifth of 1898’s arable land was planted four years later, in 1902.

Times were tough, as Javier Altarejos will tell you in Tempting Hymn. In this scene, Javier reveals the babaylan ties of one of his former employees, Peping Ramos, whom you may remember as the disgruntled cane slasher who shot a young boy in Under the Sugar Sun. Javier is speaking to the hero of Tempting Hymn, Jonas Vanderburg. The American is curious about the babaylans because he is falling in love with Peping’s daughter, Rosa Ramos.

“When I took over the hacienda, Peping was sure he could manage me.” Javier took a sip of his drink. “He was wrong.”

“So he ran off to join the madmen in the mountains?”

“They’re not all madmen—though they do attract every troublemaker on the island. The babaylan are more like the trade unionists you have in America.”

“But their popes and special charms—”

“Give them credibility.”

That credibility came from the traditional role of babaylans as priest(ess), sage, and seer. People admired the babaylans, and they would not stop admiring them just because the Americans said so. In fact, the Yanks were not able to put down Papa Isio’s insurrection until 1907—a tough reality for Americans to stomach since they had made such a big deal of declaring peace in 1902.

The declaration fooled no one because Samar was rising up again, too. In fact, Samar had a very similar movement to the babaylans, complete with its own popes and sacred amulets: the pulahans (or “red pants”). Both the pulahans and the babaylans believed that:

- an apocalyptic clash was coming;

- they alone would survive; and

- a new independent world order would be built upon the ashes of imperialism and industrialism.

If this sounds familiar, take a look at the Boxer Rebellion in China—same time, same motives, and the same ideology. It’s not a coincidence. As a teacher of world history, imperialism, and comparative religions, movements like the babaylans and the pulahans represent the intersection of everything that interests me, which is why they turned out to be such an important part of Sugar Moon‘s plot. I hope you find the politics as interesting as I do.

Featured image includes three babaylan mandalas, created by artist Perla Daly.