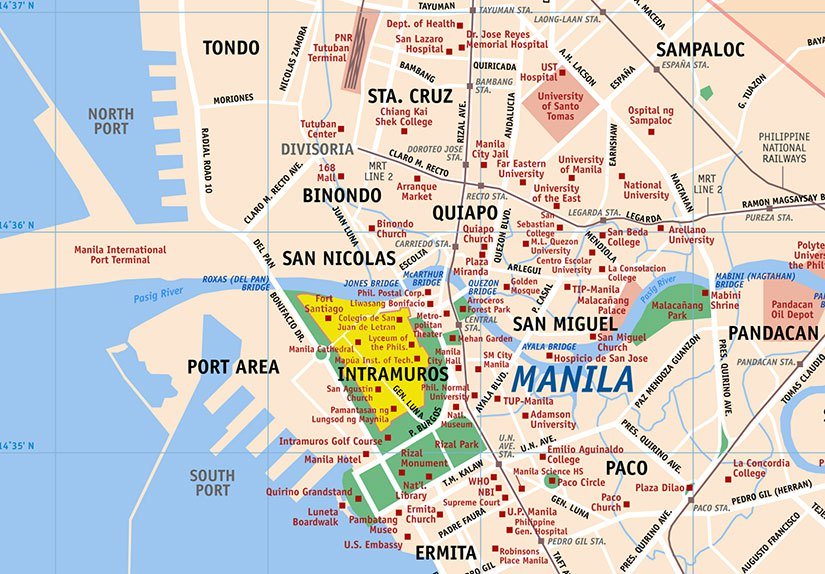

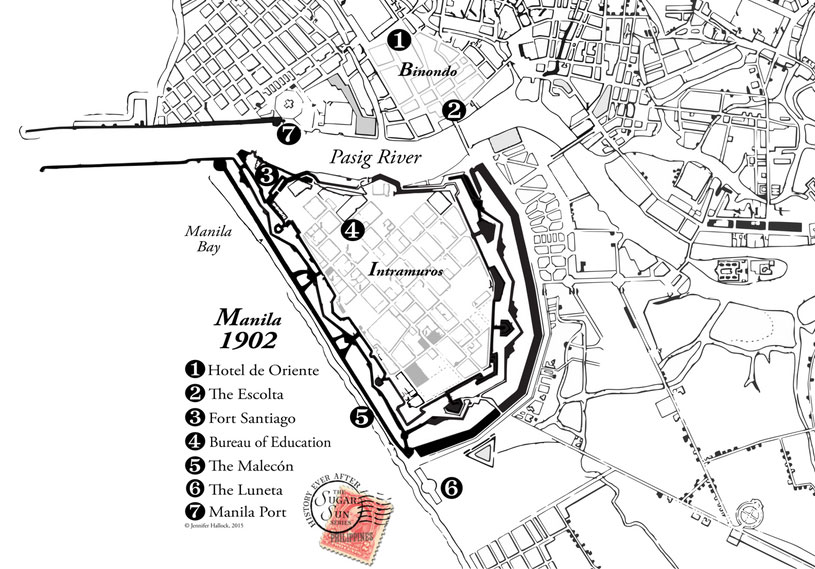

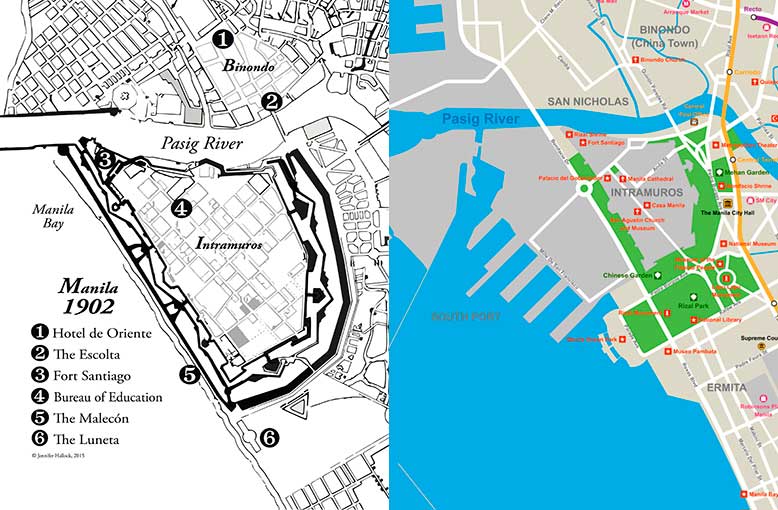

Have you heard romantic stories of evenings strolling on the Luneta, once upon a time? Or racing along the Malecón? Did you wonder where these entertainments took place? Maybe all you know is the enormous port that eats up Manila’s shoreline. If you look at the 1902 map above, though, you will see that port is not there. Not yet.

Have you heard romantic stories of evenings strolling on the Luneta, once upon a time? Or racing along the Malecón? Did you wonder where these entertainments took place? Maybe all you know is the enormous port that eats up Manila’s shoreline. If you look at the 1902 map above, though, you will see that port is not there. Not yet.

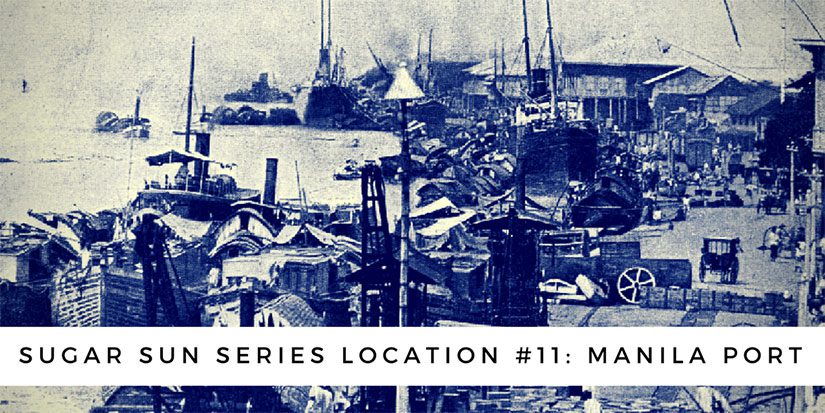

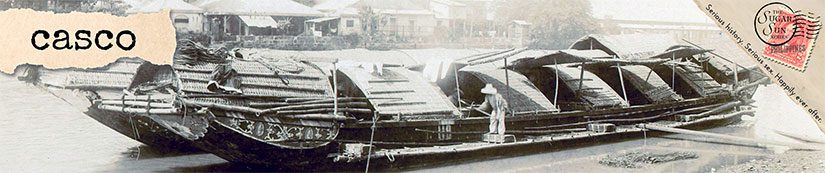

Before 1908, a visitor’s steamship would anchor two miles offshore in the rough seas of Manila Bay. The passenger would transfer to a lighter, known as a casco, and ride with their luggage into the city this way:

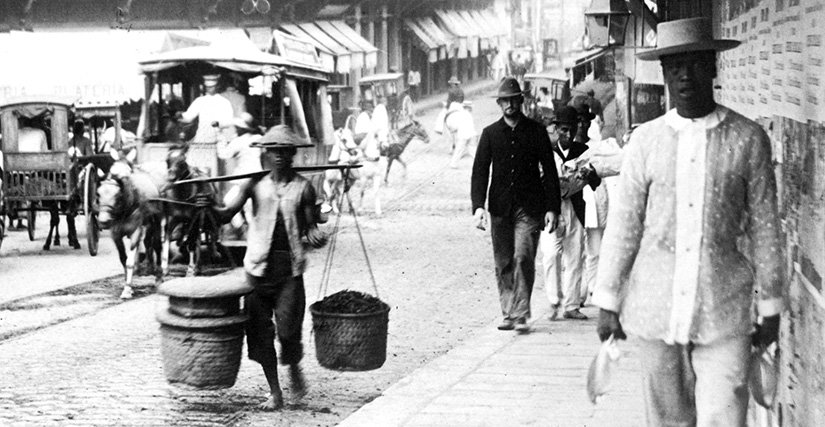

[Della’s boat] pulled past a large fort flying the American flag and headed into the mouth of the Pasig, a river as wide as the Potomac but ten times as crowded. Bossy American steamers, lighters heavy with food and livestock, outrigger fishing boats, and single-man canoes fought upstream for a space at the north-side dock. Her boat won a place and tied up in front of a huge warehouse marked Produce Depot.

This original port was on the north shore of the Pasig: in front of the San Nicolas fire station and across the river from Fort Santiago. The Yankees did not like this lighter system, though, because they thought it was dangerous and inefficient. Something had to be done, they said. Hence, one of the first major infrastructure projects of the new century was born. (The other from this time was the Benguet Road to Baguio.)

This original port was on the north shore of the Pasig: in front of the San Nicolas fire station and across the river from Fort Santiago. The Yankees did not like this lighter system, though, because they thought it was dangerous and inefficient. Something had to be done, they said. Hence, one of the first major infrastructure projects of the new century was born. (The other from this time was the Benguet Road to Baguio.)

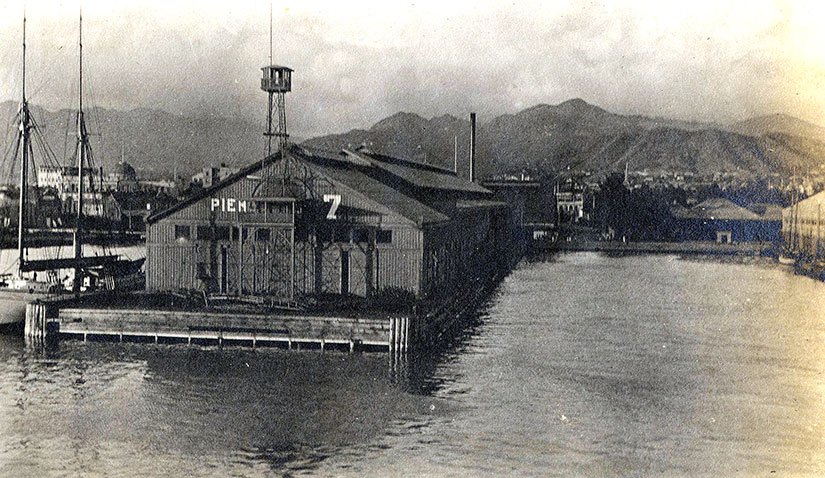

Between 1903 and 1908, the Americans would add 200 acres to the shoreline through land reclamation. The breakwater was expanded, and numbered piers lined the bay.

It was supposed to cost $2.15 million, and certainly no more than $3 million, but—as with all infrastructure boondoggles—it ran to $4 million before the construction was over. (That is $108.4 million in 2016 dollars.) Compared to Boston’s $24.3 billion for the Big Dig (a highway and tunnel project), you still might say that Manila port was a bargain. But before you believe this an example of American largesse, remember that all expenses of the Philippine Commission were paid from local tax revenues.

It was supposed to cost $2.15 million, and certainly no more than $3 million, but—as with all infrastructure boondoggles—it ran to $4 million before the construction was over. (That is $108.4 million in 2016 dollars.) Compared to Boston’s $24.3 billion for the Big Dig (a highway and tunnel project), you still might say that Manila port was a bargain. But before you believe this an example of American largesse, remember that all expenses of the Philippine Commission were paid from local tax revenues.

Moreover, the real cost would be paid by the Filipino families who used to enjoy a safe, leisurely promenade on the beach. At what expense, progress?

(This post was originally published on the outstanding website, Filipinas Nostalgia, where I will be a guest contributor. Photographs from the Philippine Photographs Digital Archive at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor.)