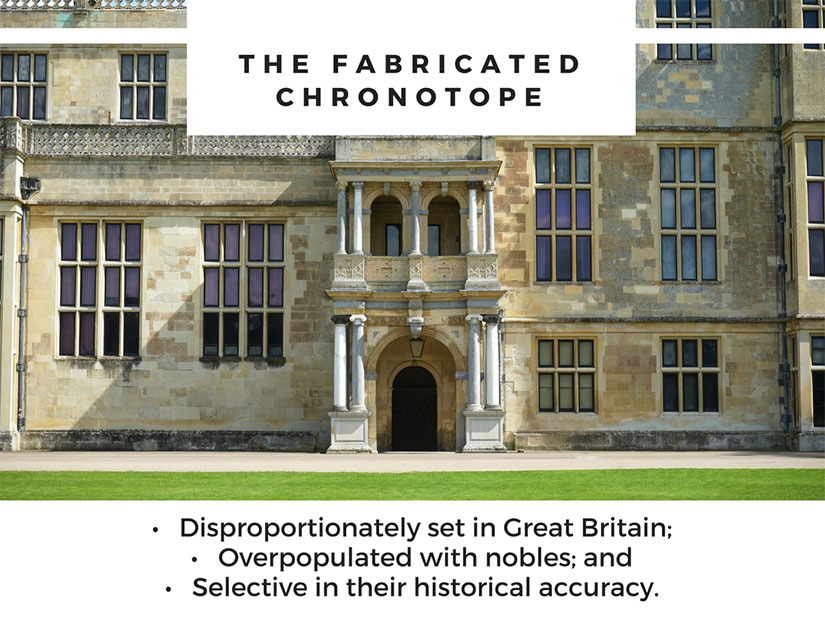

Diversity of geography, time period, and representation exists in historical romance novels, both traditionally and independently published. However, mainstream bestsellers are disproportionately: (1) set in Great Britain; (2) overpopulated with nobles; and (3) selective in their historical accuracy. These three criteria define the most popular chronotopes.

Before we break down these three observations, it’s definition time. The Literary Encyclopedia says that a chronotope is: “A term taken over by Mikhail Bakhtin from 1920s science to describe the manner in which literature represents time and space.” I am adding geography and ethnicity to this construct. Therefore, this study examines historic, geographic, racial, and ethnic diversity within English-language romance sold in the United States and written at least fifty years after the events described.

the British setting

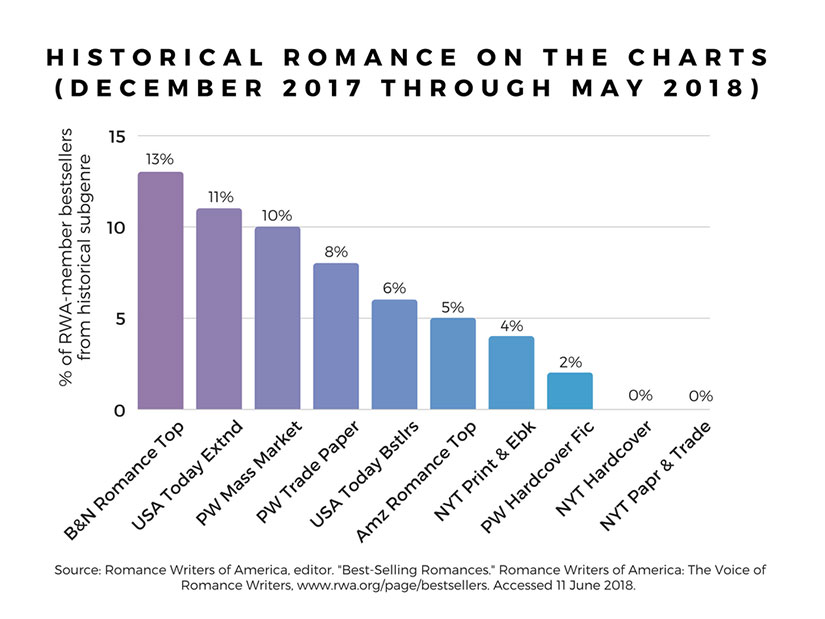

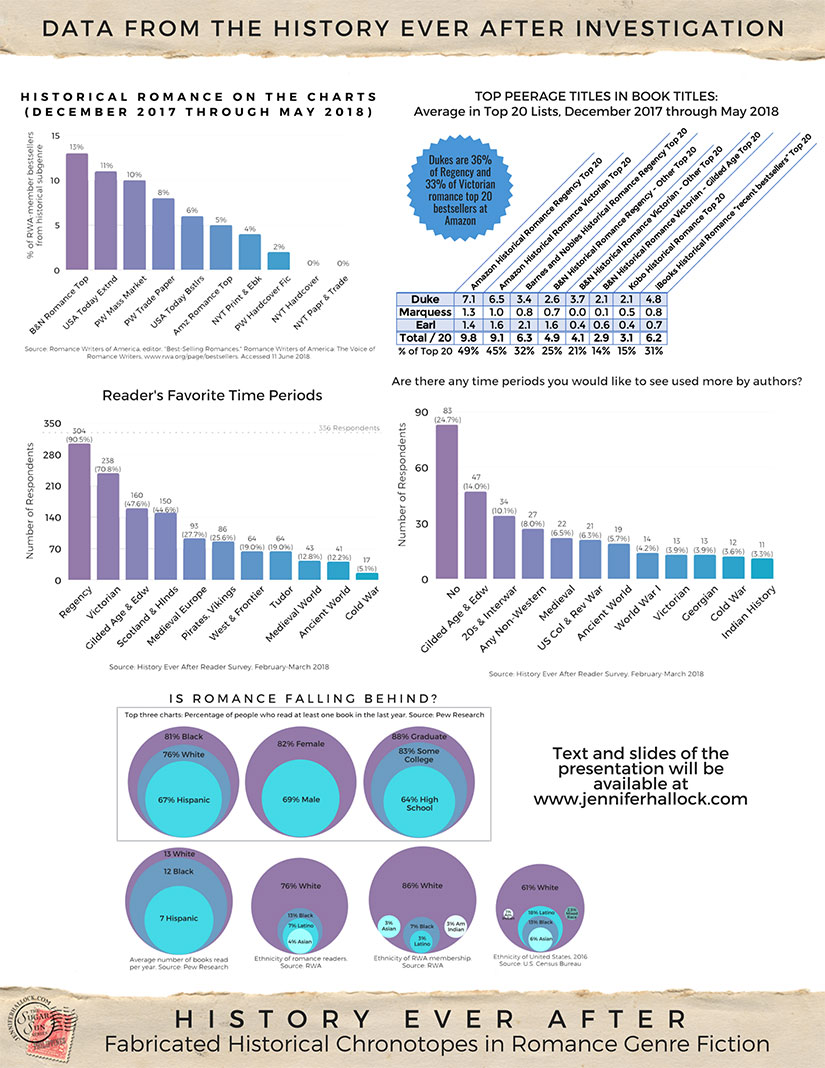

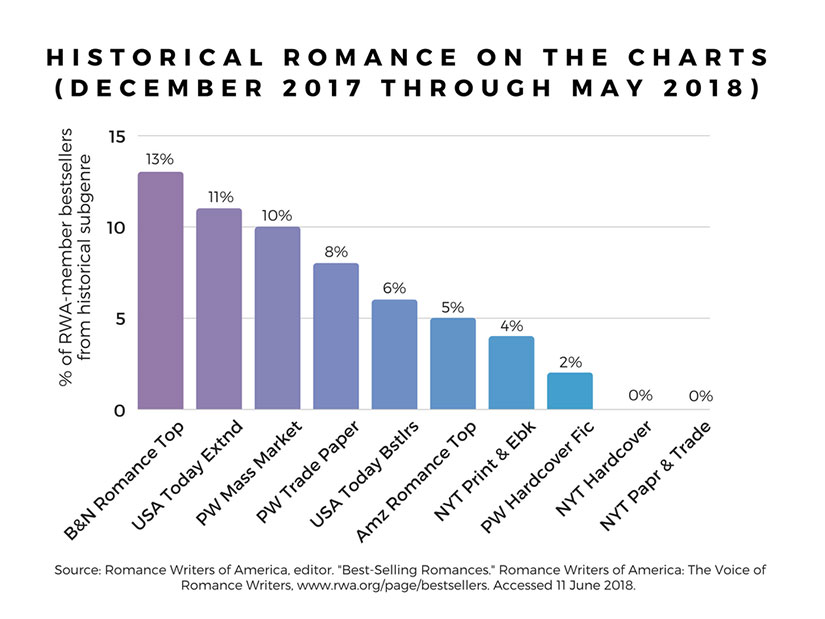

I began with bestseller data for the last six months, relying first upon Romance Writers of America to identify the bestselling books by member authors and then doing my own investigation to determine whether these romances were historicals. This past April at the New England Chapter of RWA’s annual conference, Cat Clyne, editor at Sourcebooks, called the historical market “soft.” And this is partly true: in conventional print bestseller lists, historical romances by RWA-member authors are at most 11% of bestselling romances. They have the largest market share on the Barnes & Nobles Top 20, but in total sales that may not be much. As we will see later, the role of historical romance has a larger impact than sales on the overall romance industry.

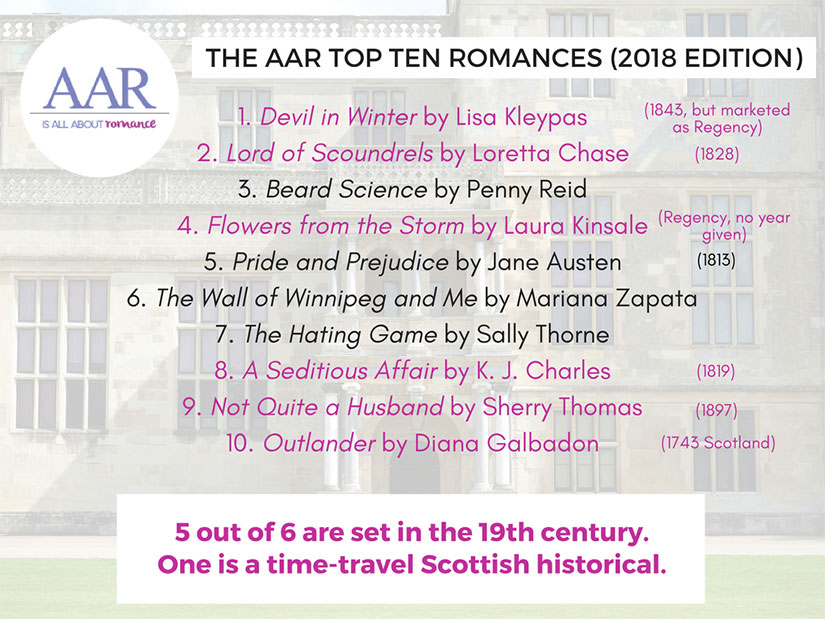

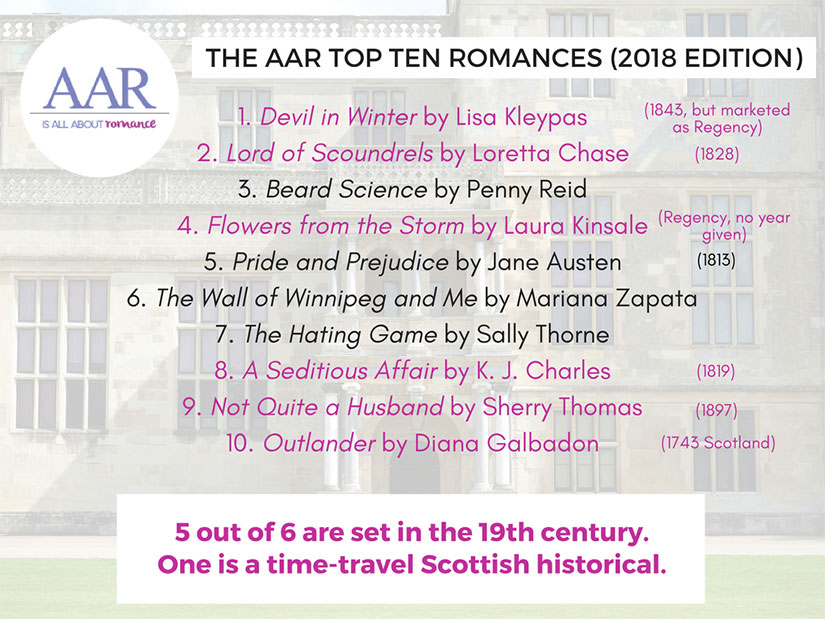

But let’s look at these 2018 bestsellers: 4/5th of them are set in one of only two periods: (1) 19th century England and (2) Scotland, in any period. Regency romance is almost half of the industry. The Regency, when Prince George ruled in proxy for his incapacitated father, George III, lasted only from 1811-1820. However, the era’s “style” may extend a decade or two on either side. Queen Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, a date that should be the firm beginning of the Victorian age. Publishers still play with this date, though, depending on how they want to market a book. For example, Devil in Winter by Lisa Kleypas—a book that earned the title of #1 romance of all time in the All About Romance readership poll—is marketed as Regency, even though it is set in 1843. (More on this poll below.)

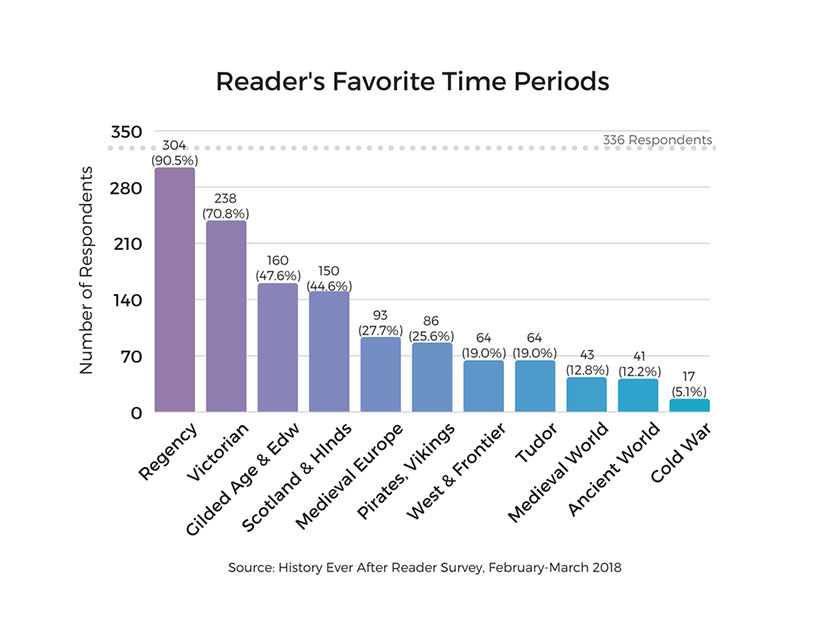

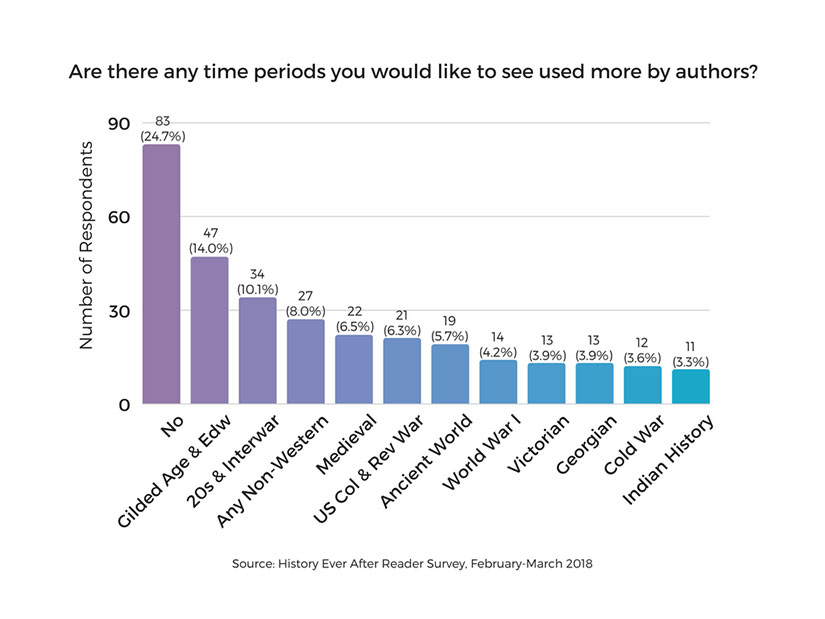

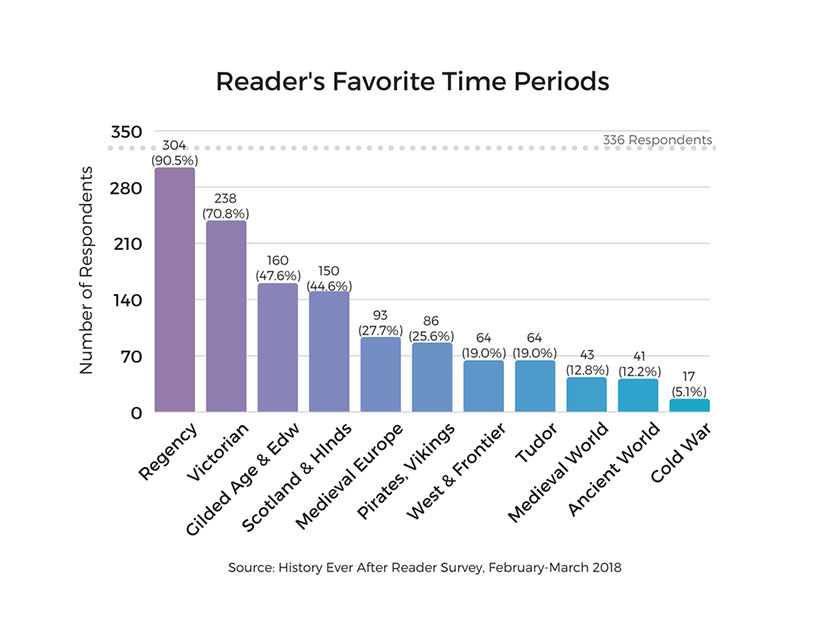

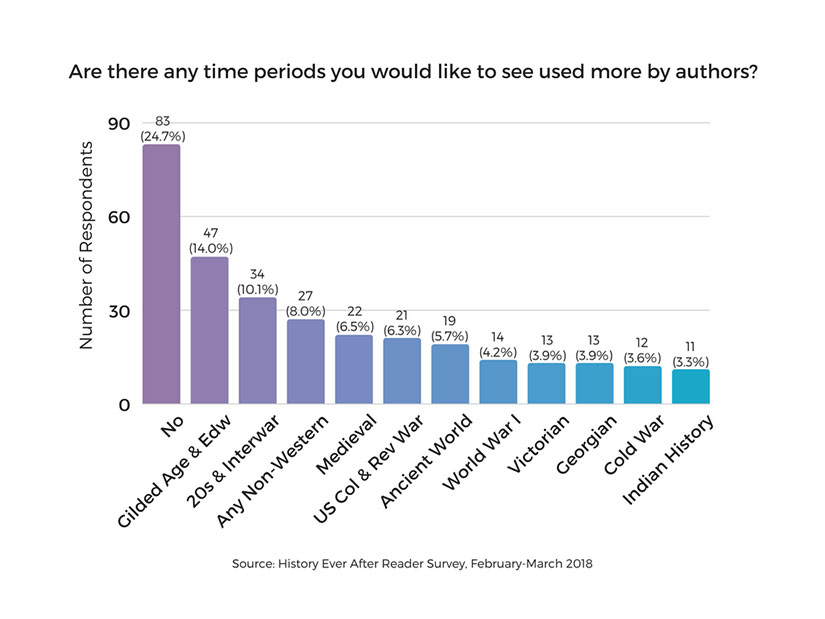

The obsession with the Regency is backed up by my own survey in February and March 2018 of 336 self-identified historical romance readers. Respondents could choose more than one favorite, and over 90% of them chose Regency, with Victorian romance following closely behind at over 70%. More revealing, actually, is the fact that when asked if there were more periods that they would like to see used in romance, 25% said no. They are perfectly sated by the dominant chronotopes that exist. (However, 8% would like to see anything non-Western, a statistically-significant number because this was a write-in response chosen independently by 27 readers.)

Critical reception follows the 19th-century British trend. All About Romance periodically identifies the top 100 romances of all time through a readership poll, and though this survey process was problematic from a social science standpoint, they do provide us with a current read on a longer-term market. Of their ranked top ten, six out of ten are historical, which skews high as compared to current sales data. Five out of these six are set in the 19th century. (The other is a time-travel Scottish romance. Ahem, Outlander.)

The British Peerage

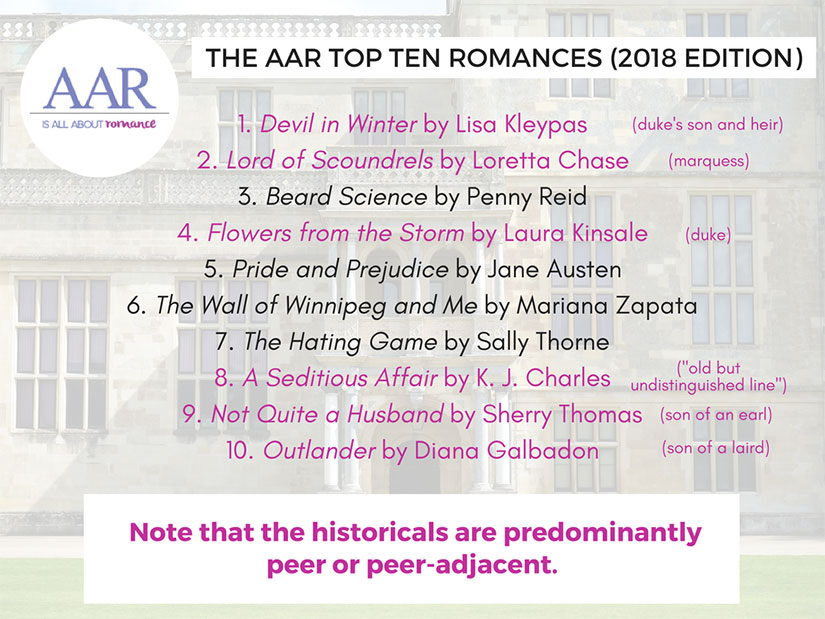

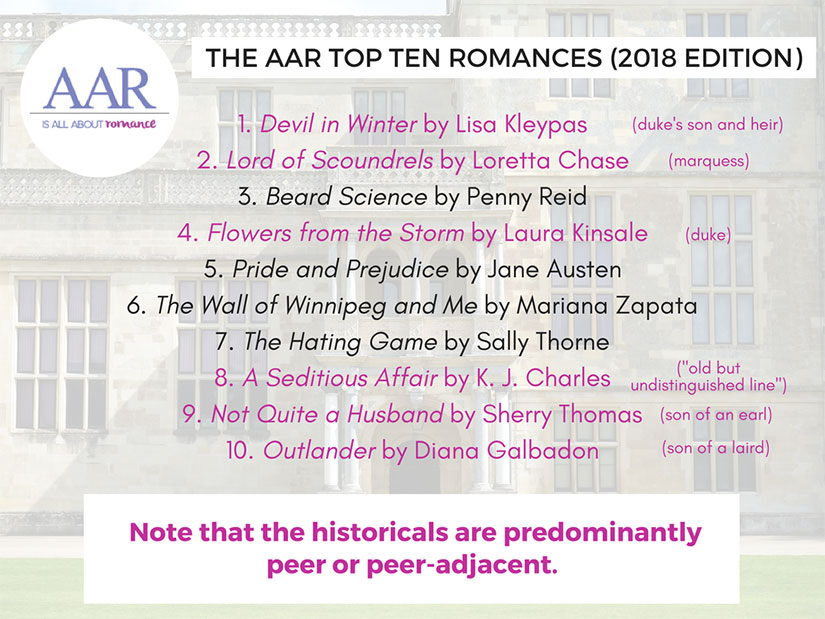

Another characteristic illustrated by the AAR poll is the obsession with the British peerage: five out of six historicals dealt with peers or lords and their heirs. Only KJ Charles has a relatively elite gentleman without a family title. Moreover, her book breaks class and sexuality assumptions that exist within the chronotope. This proves that alternatives do exist, and they do garner critical and reader attention—but note that this book is still not available in paperback and therefore will have a hard time making the conventional bestseller lists. And keep in mind that this is the only one of six that broke the mold.

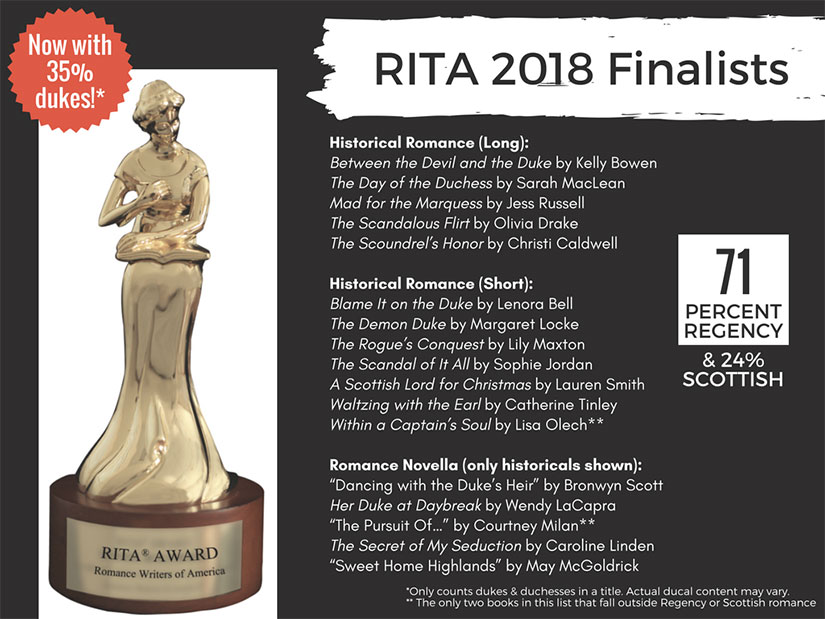

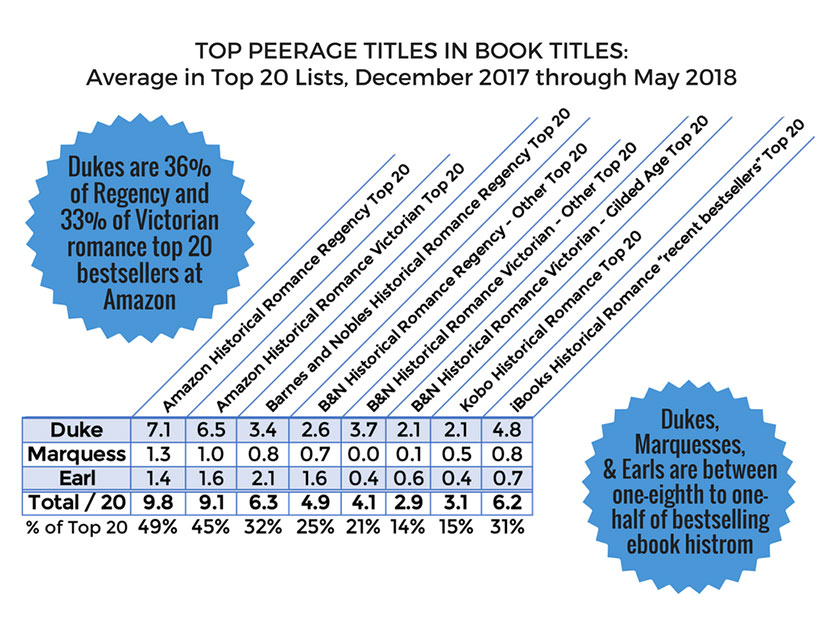

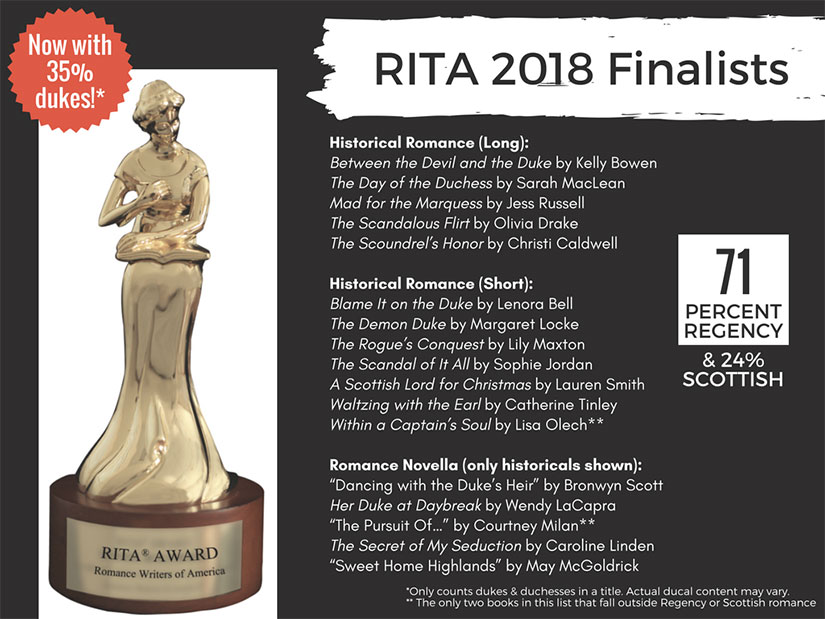

The 2018 RITA finalists showed a similar result: out of the seventeen finalists in historical categories, including historical novellas, 71% were set in the Regency and 24% were set in Scotland (with some overlap between those two). That is a total of 88% set in these two chronotopes. Note that 35% of these finalists have duke or duchess in the title—not in the book, but in the title.

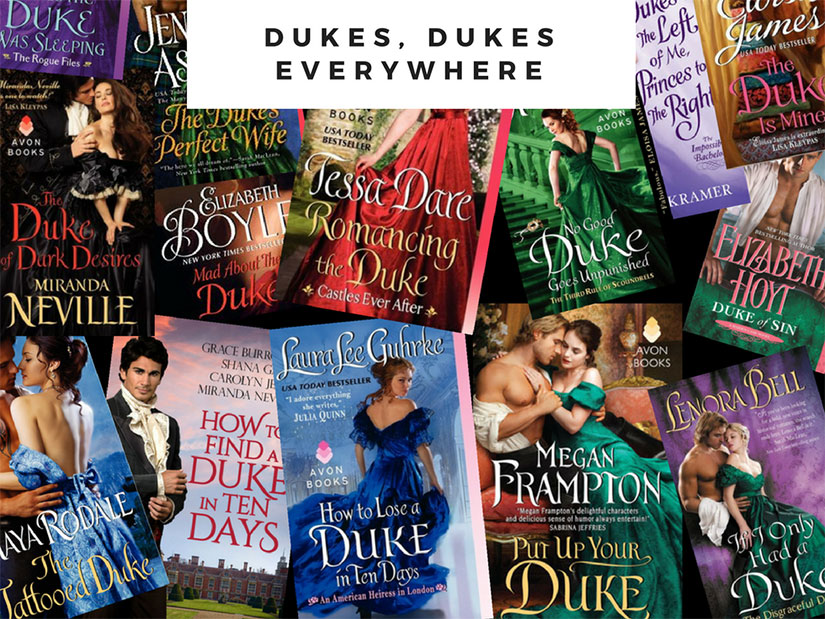

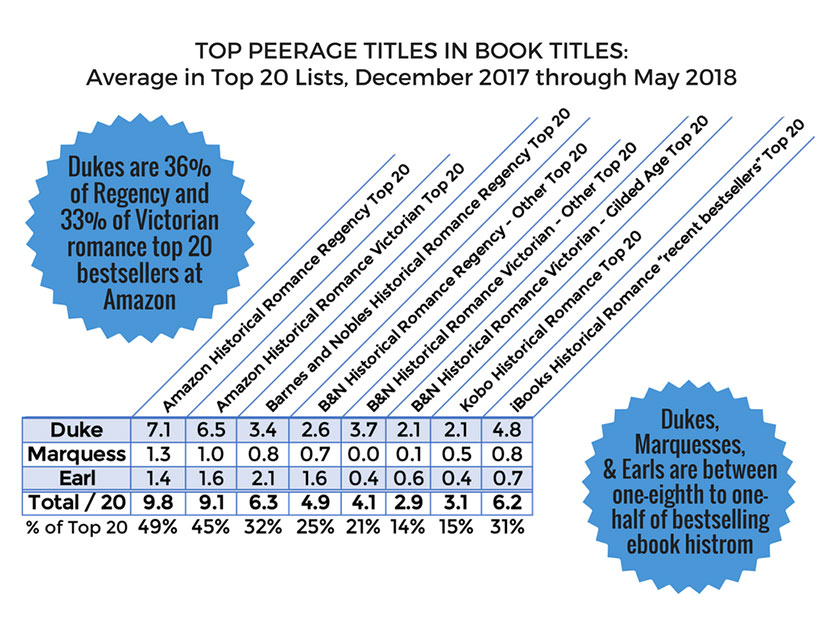

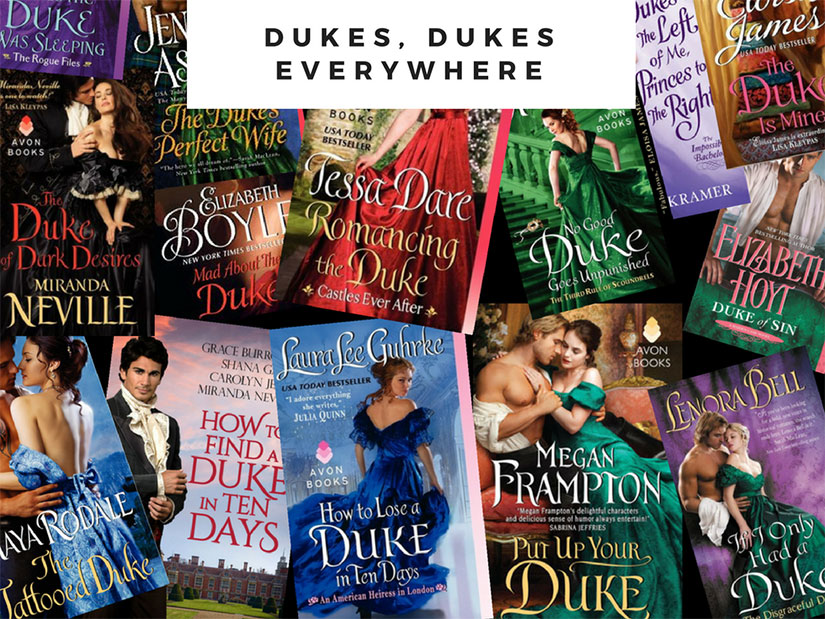

Neither the AAR poll or the RITAs are outliers: in the past six months, over one-third of the top 20 Regency and Victorian romances on Amazon’s bestseller lists have included either duke or duchess in their titles. If you extend that count to marquess and earl, the numbers jump to one half. In my industry producer survey, one author called this the 10,000 dukes problem.

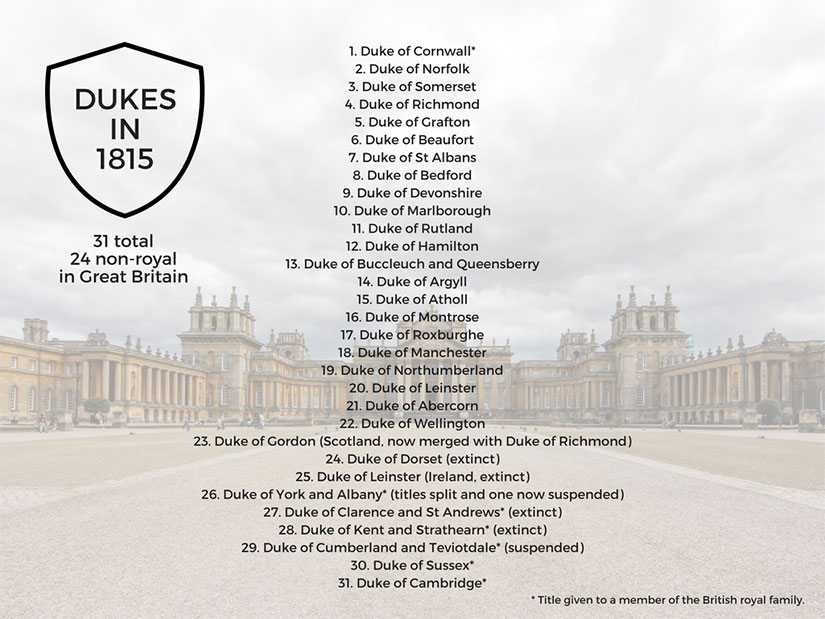

Several other authors reported that they had been asked to change the settings of their novels to Regency, and often specifically to dukes. One wrote: “Hero had to be a duke (again) to improve marketability. This is ridiculous. There were at most a couple dozen dukes running around Regency London at once, and they were not all tall, dark, grouchy, and in want of female companionship. Try telling my trad house editor that.”

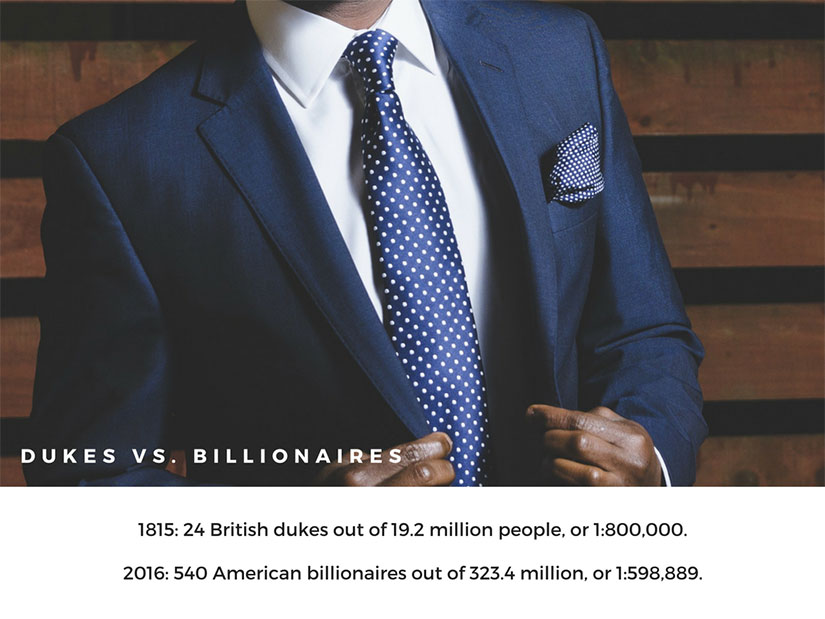

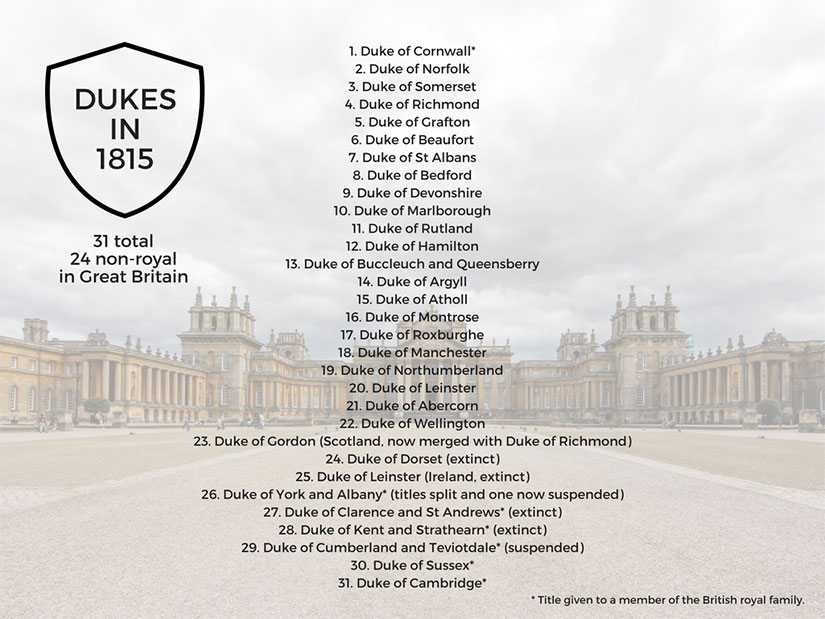

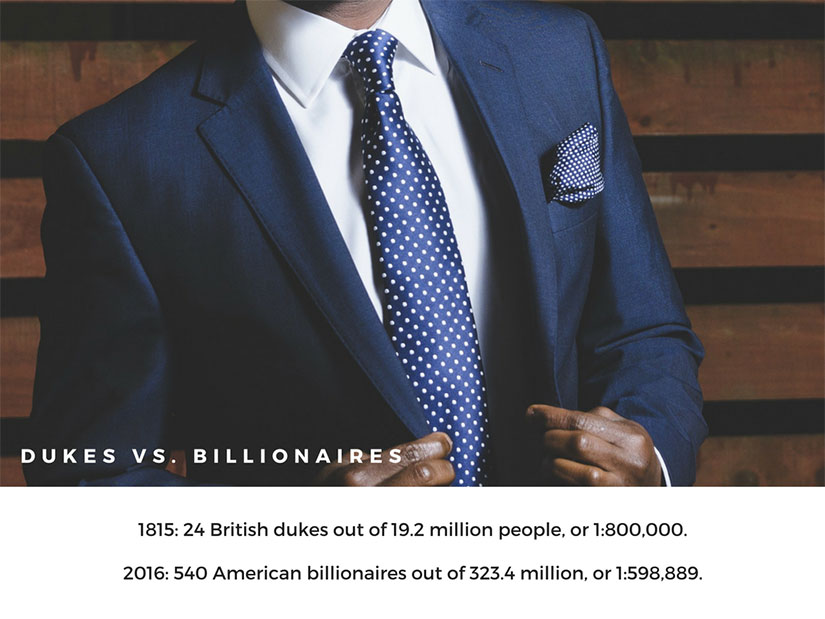

This author was on the money: there were 24 non-princely dukes in 1815, out of a British population of 19.2 million. These dukes averaged over 50 years of age, and if you have ever seen The Supersizers Go “Regency,” which is recapped at Just Hungry, the period diet would not quite leave one with chiseled abs. You may remember the era of baron romances, so where did all this peerage inflation come from?

Mary Lynne Nielsen suggested this may be a symptom of rising wealth inequality in the US. The appeal is not just the power that comes with money, but the perceived security that this money brings. It is a similar phenomenon to billionaire books in contemporary romance, though it is easier to run into an American billionaire today (1:598,889) than a Regency duke in Britain (1:800,000).

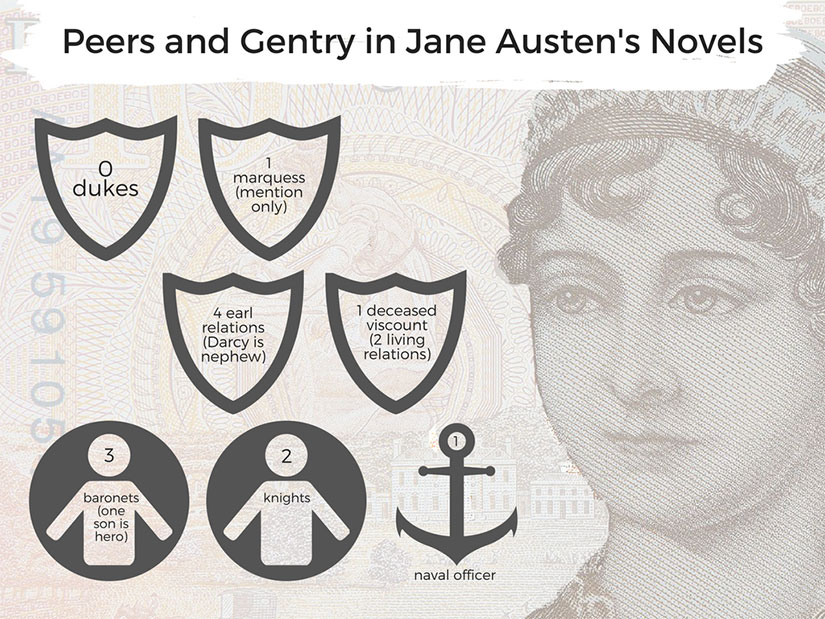

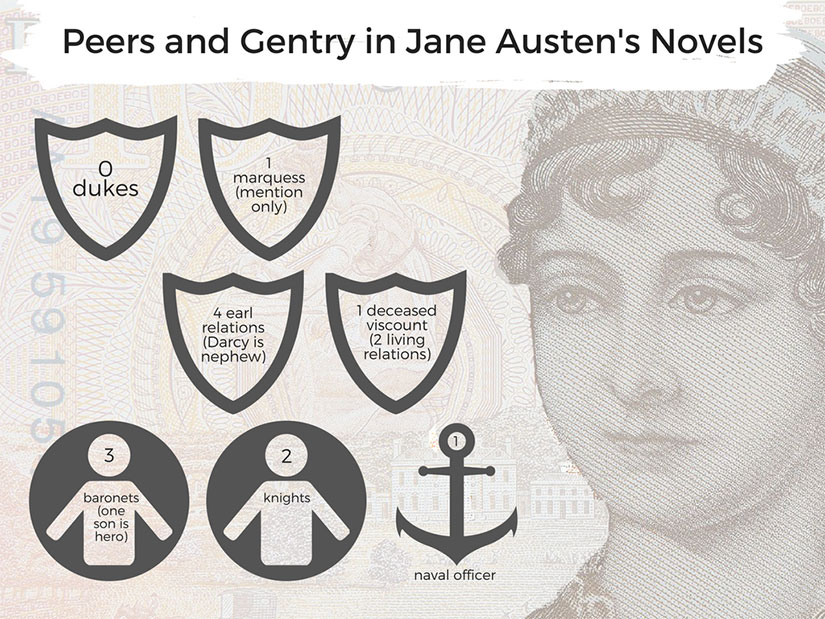

Despite the fact that Pride and Prejudice earned the 5th place spot on AAR‘s survey, Jane Austen is not really to blame for this duke obsession. First, while some claim their love for the historical romance genre stems from Austen’s work, she wrote contemporary novels. Some would argue, moreover, that these are comedies of manners with romantic elements rather than romance genre books. But, most importantly for our peerage discussion, Austen only mentioned a duke once, in the most passing of ways, according to the Jane Austen Wikia. Fitzwilliam Darcy was the nephew of an earl, the closest Austen ever comes to a peer hero.

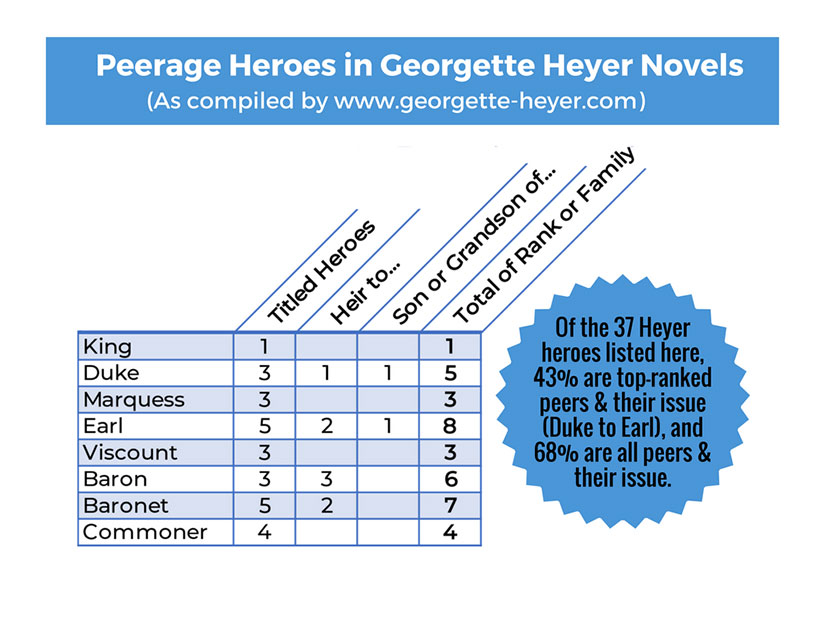

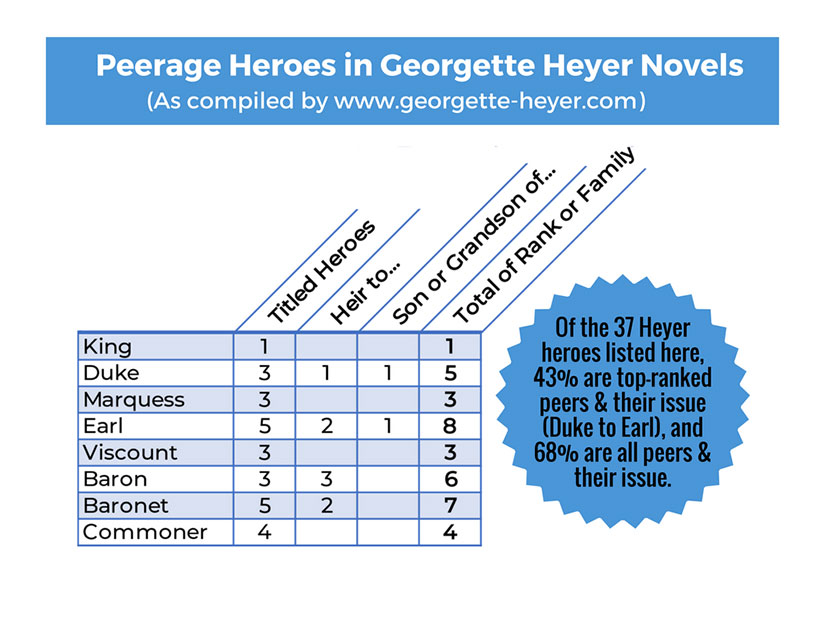

Georgette Heyer, on the other hand, was much more interested in peers, especially in her Regency novels. 43% of Heyer books have duke, marquess, or earl (or their issue) as heroes; and if you consider all peerage ranks (down to baron), 68% of Heyer’s heroes are peers or their issue. According to Laura Vivanco, the bestselling authors who shaped the modern standard of Regency—including Stephanie Laurens, Mary Balogh, and Mary Jo Putney—cite Heyer as their inspiration. Everyone claims to love Austen still, but do we love a Heyer-istic or chronotope remake of what we expect Austen to be, possibly based on our film and television adaptations of her work?

Historical Selectivity

Let’s look more deeply at our Regency heroes and where they got their wealth. One author in my survey commented:

For bigger picture things, I hate that there’s so little acknowledgement in historical British-set stories where wealth comes from. They might have a throwaway line about ‘sugar’ or ‘land in Jamaica’ or ‘sent to India to make his fortune,’ but there’s absolutely no acknowledgement that this wealth is built on the backs of slaves or violent oppression. I don’t want every historical I read to be a history lesson on the evils of slavery but this refusal to even nod to the realities of historical fact completely erases entire continents and populations from their place in history.

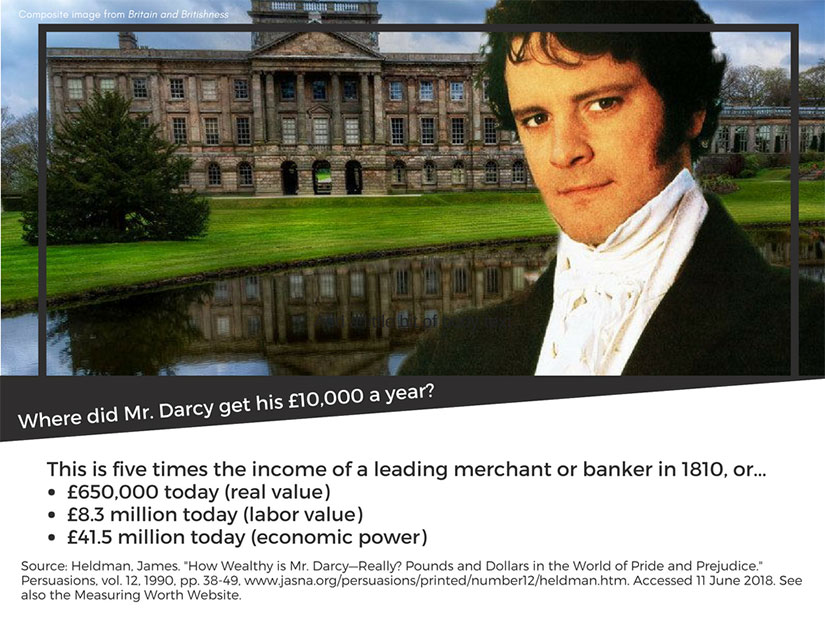

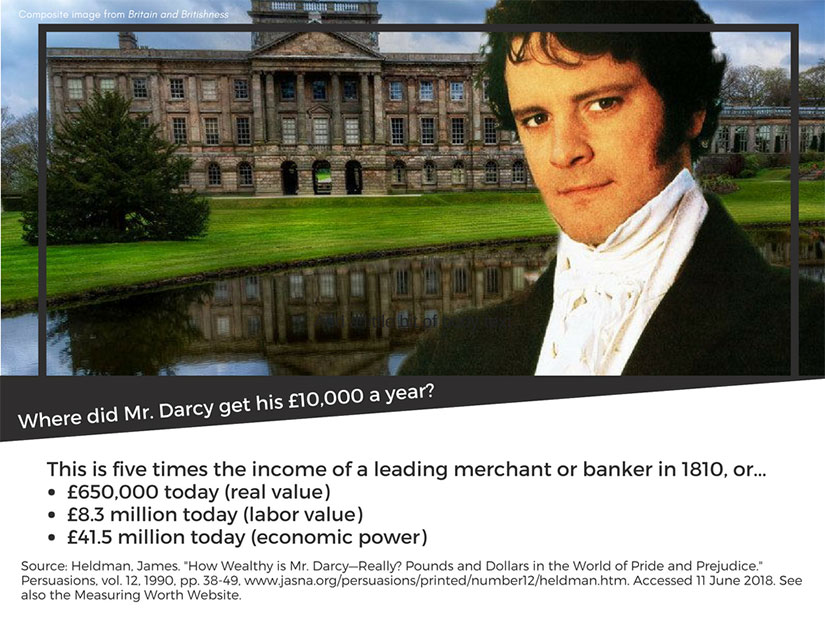

For all the reasons mentioned above, it is unfair to pick on Mr. Darcy—except for the fact that Jane Austen gave us a figure: £10,000 a year. This may have been an exaggeration, but it is a number to start with. How much does this mean in modern terms? Well, it depends on how you measure the purchasing power of the money, but it could be a princely sum. Where did he get this money? Tenant farmers? Coal mines? Sugar trade in the Indies? Why don’t we ask?

The chronotope is selectively inaccurate when realism endangers the happily-ever-after. Can you have a happily-ever-after with a slaveowner? (No. And I know there was a 2015 RITA finalist with a Nazi concentration camp commandant, but let’s not go there.)

The popular chronotope of 19th century Britain avoids such issues by erasing these uncomfortable aspects of history from the story. And yet the authors I surveyed claimed that accuracy was extremely important to them, and in impressively specific ways. For example, when was the doorknob invented? Ella Quinn will tell you that it was not until June 8, 1878, that Osbourn Dorsey filed the patent for a turning doorknob. There were no doorknobs in the Regency. Some readers who are sticklers will pan a book for a doorknob, waltzing before the scandalous dance was introduced, decorating a German-style Christmas tree in Regency England, or using peerage titles incorrectly.

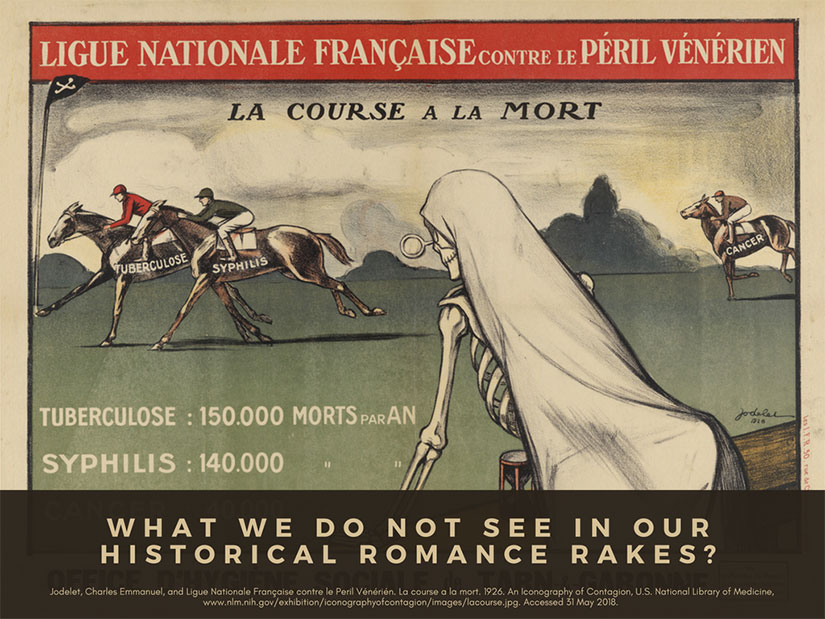

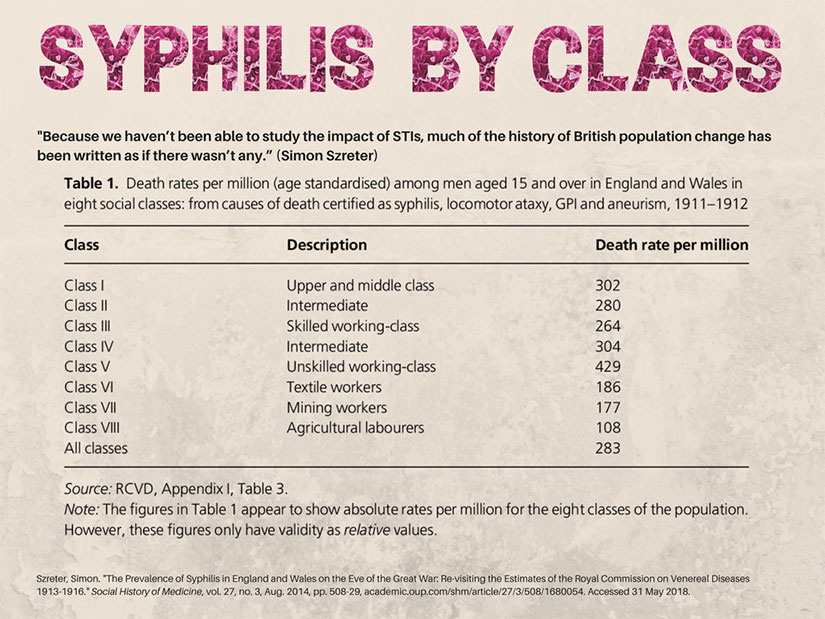

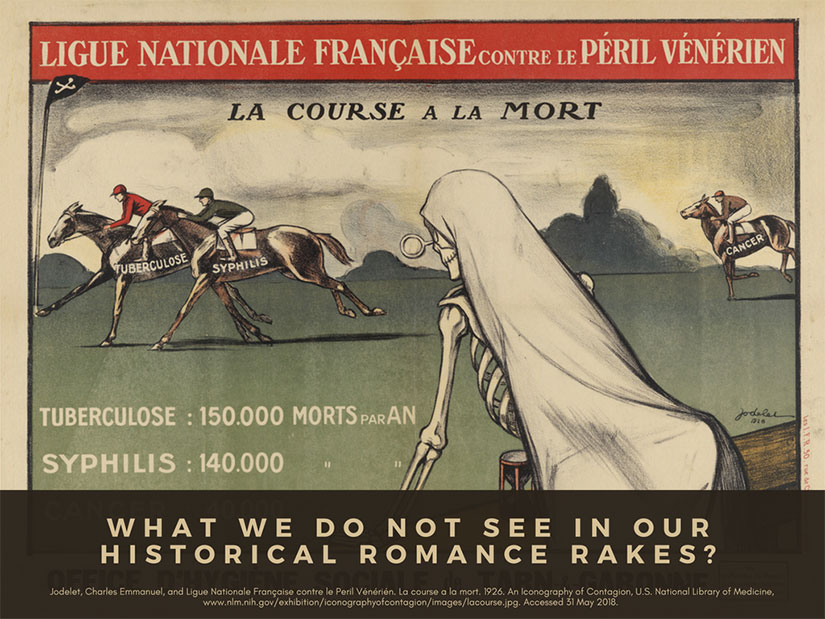

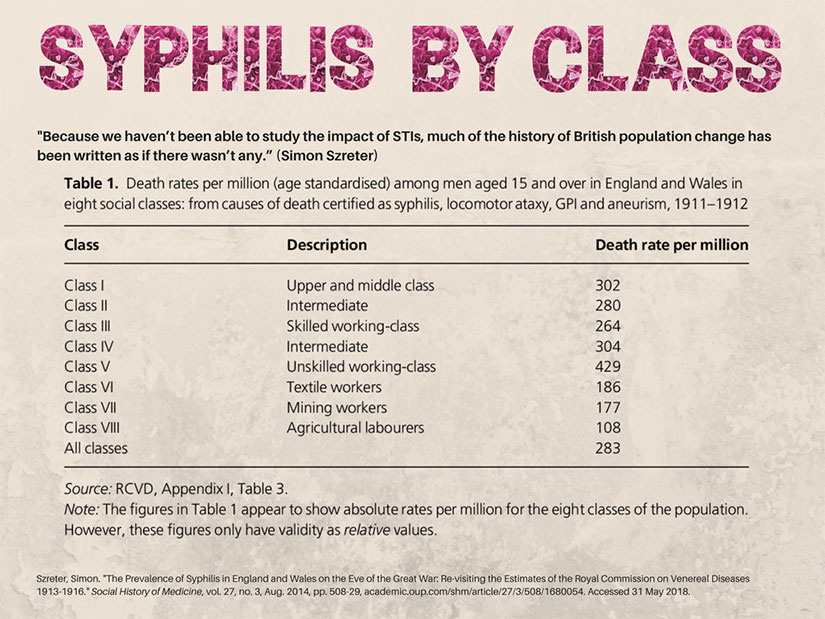

And yet no hero has syphilis. Of course not because it is a reality that does not fit the romance genre requirements. There can be no HEA with syphilis. Until penicillin was widely introduced in the 1940s, the recovery rate was 1%. After a latency period (3-15 years), the disease caused seizures, internal bleeding, physical deformations, loss of motor functions, organ failure, dementia, aneurysm, and death. We know that taming the Regency rake is a common trope—and where does one become a rake other than with a mistress, or at a gaming club, or brothel, where it had to be easy to contract syphilis through sexual contact. Honestly, though, it was easy to contract syphilis anywhere: between 8 and 15% of the general population was infected with this disease in the 19th & early 20th centuries. And because of the latency stage, you often did not know you had it. Doctors would often not tell their patients that they had syphilis, nor would they tell a man’s wife about his diagnosis, even though he was 92% likely to give it to her within the first year. [Read more about medicine in the nineteenth century here.]

And being wealthy or a duke did not protect you from this scourge. In fact, you were more likely to die from the disease than your textile workers, coal miners, or tenant farmers. Being young didn’t help either: based on records of Chester, England, 8% of our heroes should be contracting syphilis before age 35. But they don’t, and this is why the Regency chronotope works.

Advantages of the Regency Chronotope

Let’s stop talking about syphilis. Let’s be historically selective for the purposes of a happily-ever-after, character-driven story: this is “escapism.” One blogger called this chronotope a “Never-Neverland mash-up that’s been dubbed ‘The Recency’ or ‘Almackistan.’” I have also heard it called a “wallpaper historical,” a ”costume drama,” or a “Disney Regency.” It is a cleaner, safer, prettier, better-smelling, and happier world than the real Regency ever was.

Best of all, there are low barriers to entry, for both readers and authors. A reader can jump into a new duke Regency as easily as an episode of a favorite television program. It takes only a little marginal effort to start a new book, or a new author, or a new series. Because the history and rules are already known before the reading begins, the author can dive right into character development. The key research for the author is reading more of the same. One author, Maggie Mackeever, advised prospective authors to ”Immerse [themselves] in Georgette Heyer” and to “Read until [they] have the era fixed clearly in [their] head[s].” In other words, Regency dukes are commodities. We can buy and sell them easily on the free market—in novel form, of course.

Where is the harm in this? A good book is a good book, right? With an audience who understands how this world has been fabricated, any reader can enjoy a Regency duke story. No single book, author, publisher, or reader is wrong. Read it all! But there are problems, in the aggregate. To find out what the are, read part two of History Ever After.

(To go back to the History Ever After content page and find the handout flyer, click here.)

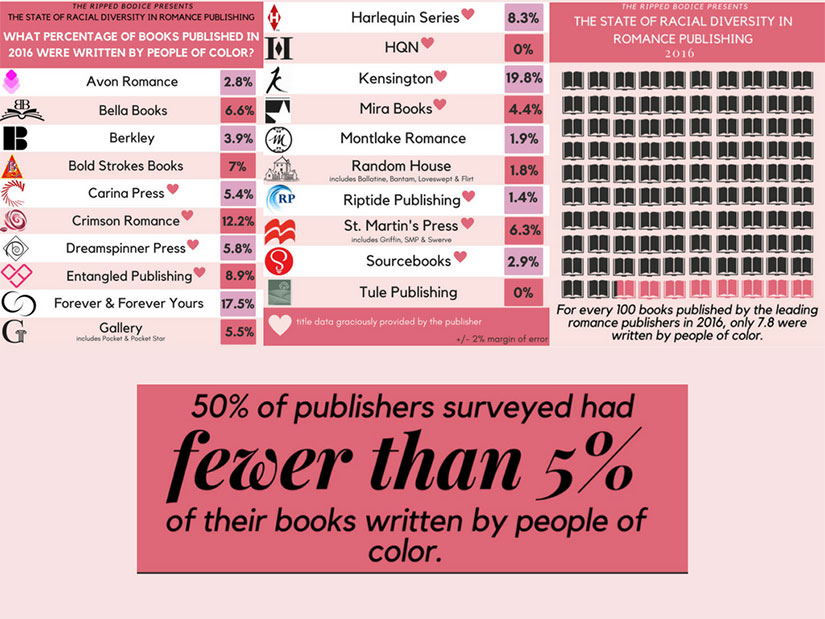

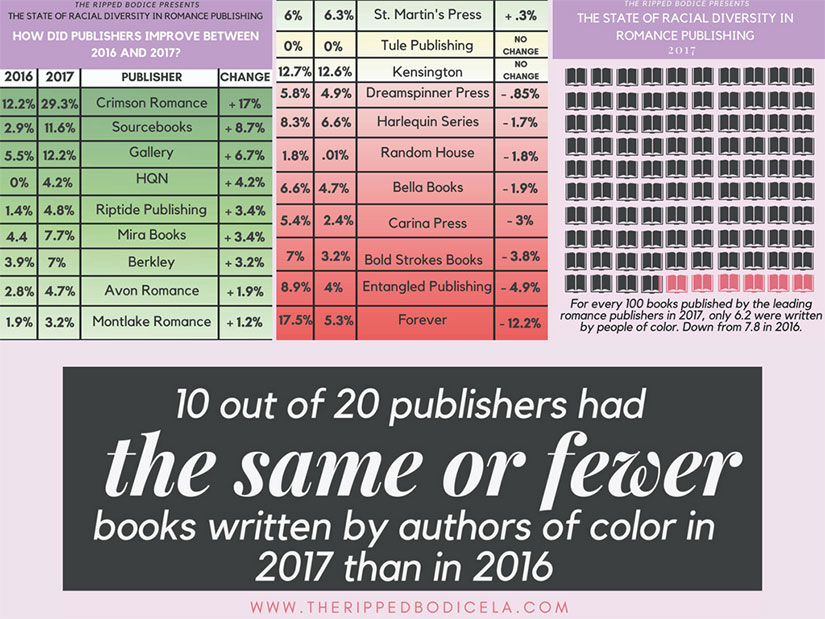

Fifty years on from Nancy Larrick’s study, we’re not doing any better in Romance, according to the Ripped Bodice’s

Fifty years on from Nancy Larrick’s study, we’re not doing any better in Romance, according to the Ripped Bodice’s

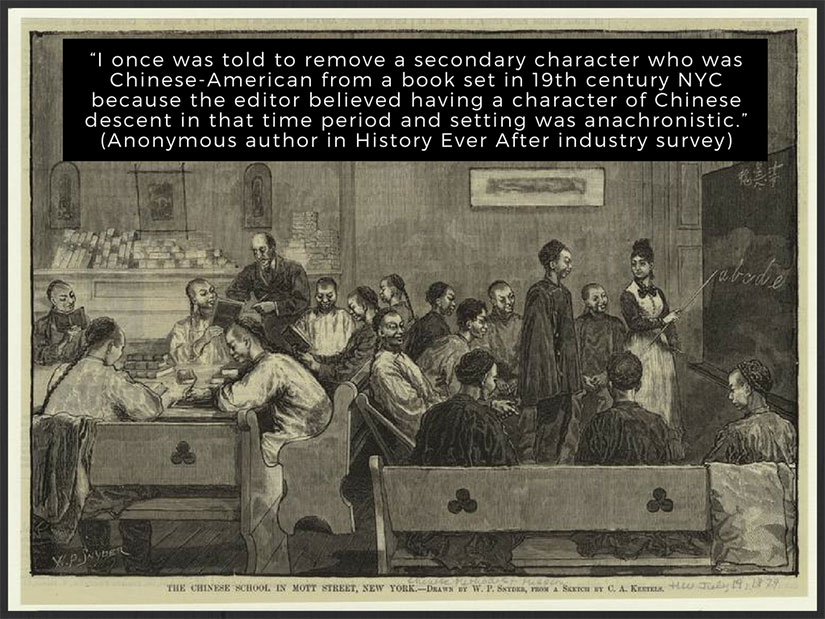

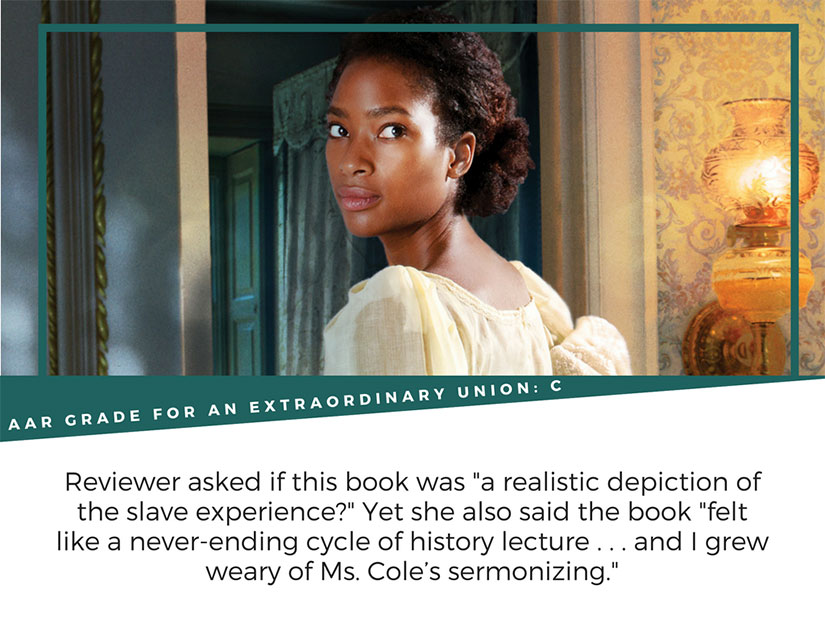

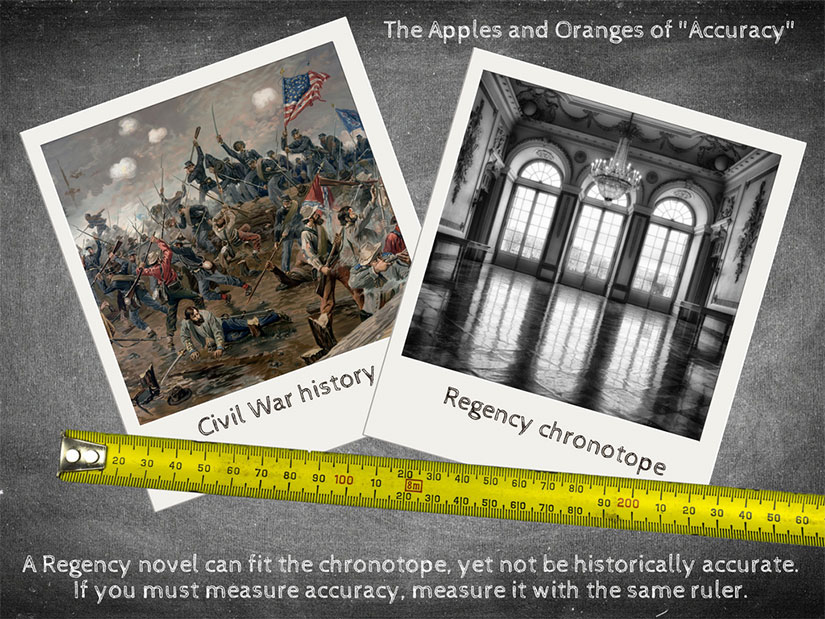

This is a double standard. Since there is not a pre-established model for diverse Civil War romance, An Extraordinary Union was compared to the inappropriate standard of historical fiction. No romance novel will stand for everything about slavery or the civil war. It can and should be a window into that history, but the world-building has to be done very explicitly to allow for a romance to develop between two characters and to make room for their HEA. Alyssa Cole’s Loyal League series is immersed in extensive research, down to a pro-Union insurrection within the Confederacy—an understudied part of the Civil War—but critics need to allow Cole at least a portion of the same authorial agency that they give to Regency duke stories. Overall, this series is more accurate than much in the Regency chronotope.

This is a double standard. Since there is not a pre-established model for diverse Civil War romance, An Extraordinary Union was compared to the inappropriate standard of historical fiction. No romance novel will stand for everything about slavery or the civil war. It can and should be a window into that history, but the world-building has to be done very explicitly to allow for a romance to develop between two characters and to make room for their HEA. Alyssa Cole’s Loyal League series is immersed in extensive research, down to a pro-Union insurrection within the Confederacy—an understudied part of the Civil War—but critics need to allow Cole at least a portion of the same authorial agency that they give to Regency duke stories. Overall, this series is more accurate than much in the Regency chronotope.