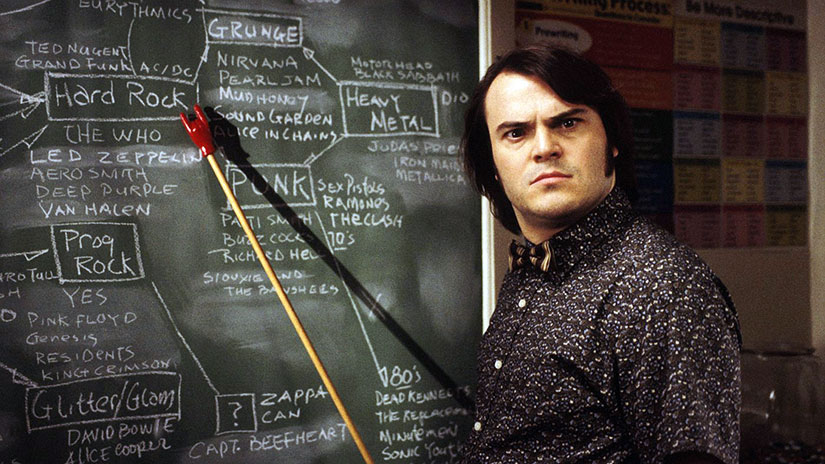

With apologies to Better Off Dead (1985):

Teaching can be one of the most emotionally rewarding professions out there, which is why most teachers still scrape by on the low salary. (Notice that I did not say “accept the low salary” because I do not accept it. This country’s priorities are totally screwed up.)

The best part of the job is when your students tell you that you’ve made a positive difference in their lives. This may be an academic difference (you sparked a life-long interest in a subject) or a personal boost (you gave the support that he or she needed to deal with a tough problem). If you are a new teacher, trust me: both of these things will happen…eventually.

But do not shoot for popularity right out of the gate. In the teenage world, popularity is fleeting—and it is not handed out for the best of reasons. I mean, you have seen Breakfast Club or Mean Girls, right? (Or, my favorite, Heathers? It’s a little twisted.)

Respect means so much more than popularity. Even if a student does not like your subject, does not like his or her grade, or does not even like you, he or she might still respect what you do and how you do it. That will have to be enough.

The following is what I have learned in twenty-two years in the classroom:

[Note: These twenty-two years were all spent in college-prep high schools. This does not mean my advice cannot apply to a more general educational environment (whether continuing education, at-risk youth, or college). But it might not. I don’t know. Use your best judgment.] Kids will not judge you by where you went to college or graduate school, so take that silly pennant off the wall. In fact, the more impressive the name of the school you went to, the less they want to know about it. It reminds them too much of their own college stress.

Kids will not judge you by where you went to college or graduate school, so take that silly pennant off the wall. In fact, the more impressive the name of the school you went to, the less they want to know about it. It reminds them too much of their own college stress.

They will not judge you by what you know, but by how well you explain what you know. That is one of your jobs as a teacher: to untangle, sort, classify, and construct digestible chunks of information for your students. There is nothing less cool than an adult trying to be cool. Kids want a captain at the helm of the ship. Not a Captain Ahab on a fanatical mission, or a cruel, by-the-book Captain Bligh—but a captain, nonetheless. You are asked to evaluate students—in a permanent, and sometimes public way—and they must trust your maturity, experience, and judgment to do so.

There is nothing less cool than an adult trying to be cool. Kids want a captain at the helm of the ship. Not a Captain Ahab on a fanatical mission, or a cruel, by-the-book Captain Bligh—but a captain, nonetheless. You are asked to evaluate students—in a permanent, and sometimes public way—and they must trust your maturity, experience, and judgment to do so.

If you have to discipline a student, pull him or her aside and speak privately. Remember that students are learning how to be adults, so treat them how you want them to treat others.

If you have to discipline a student, pull him or her aside and speak privately. Remember that students are learning how to be adults, so treat them how you want them to treat others.

Have a sense of humor. Even better, have patience. When you’ve lost your patience, you’ve lost the room.

Have a sense of humor. Even better, have patience. When you’ve lost your patience, you’ve lost the room.

Remember that the kids believe their time is valuable: every minute in class is a minute not learning another subject, not running on a field, not making friends, not flirting, not eating, and (most importantly) not sleeping. They have stuff to do, and to them none of this stuff is trivial. So, if they have to be in your class, make it count.

A lot of folks will give you the advice to “warm up” your class for five minutes by talking about their lives or the latest tv shows. Here’s my problem with this idea: by shaving off time here or there, you are teaching your students that class time is subjective. How can the first five minutes not be important when the remaining minutes are? Because you are the teacher and you say so? (This kind of specious reasoning does not fly in teenager-ville.)

I treat every minute of class time as valuable. When the bell rings, we get started. Yes, I tend to start by making announcements, which is a warm up of sorts. I might even talk about current events that are directly relevant to your class material. But I expect my students to pay attention. In fact, I expect them to pay attention all the way until the bell rings again. And, if I have time left over after my planned lesson is finished (ha!), I always have a backup activity or two that I can throw in: review, writing, upcoming prep, etc.

One caveat: if you teach longer than 50-minute class periods, I understand the need to break the class into two “sessions,” with a small break in the middle. But once the break is over, get back to it.

If you have nothing of value for your students to read, write, or drill at night, do not give them make-work. My subject, history, is full of endless reading, but I never, ever, ever give students an assignment that I have not pre-read and pre-approved. If there is a middle section to that reading that is not valuable, or is boring, or is badly written, I cut it out or tell them to skim it. If you give students a bad assignment, they will no longer prioritize your work in the future. Teenagers are rational actors…sometimes.

While I do not teach classes that are pivotal to the college admissions process—I teach 9th grade, before they are applying, and 12th grade, as they’re sending in the forms—my students still do the homework in my class. They even claim to find it interesting. Are the Bhagavad Gita or Enuma Elish really relevant to their lives? (Well, they might be—the Gita, in particular. Its themes are timeless!) But I think my kids read this stuff because I give them pieces that are accessible, important, and interesting. (And challenging, too, but a reasonable challenge.)

As my former colleague and star teacher, Rachelle Sam, says: “Leave room for zest.” Students will find anything interesting if you can show them it is interesting. I teach world religions, and my students have a game going every year (which I do not encourage) about which tradition I call my own. They actually debate this question with each other, and almost every religion we study is in the mix. I hope that this means that I am treating each unit with equal enthusiasm and esteem.

One reason that energy is so important is that you are teaching students how to approach the material. They will remember how you tackled difficult problems, how you found answers to questions you did not know, and how much you truly enjoyed the journey. You are teaching them how to learn. That is far more important than content, which they will not remember so well in a few years. (Remembering it for the test is hard enough for many of them.)

One reason that energy is so important is that you are teaching students how to approach the material. They will remember how you tackled difficult problems, how you found answers to questions you did not know, and how much you truly enjoyed the journey. You are teaching them how to learn. That is far more important than content, which they will not remember so well in a few years. (Remembering it for the test is hard enough for many of them.)

Now, you might notice that I have said two seemingly contradictory things: (1) your job is to communicate content, but (2) they will not remember content. Both may be true, but that does not mean teach nothing at all. Students need to learn rigor and skills, but they can only do so by working with content. Hold them accountable for a reasonable amount of material—but know that in the medium and long term, they will remember you and the skills you taught them more than that stuff you talked about.

Plan your assignments to build upon each other. Start with the most discrete building block of a skill, and then add to it in successive assessments. For example, before I ask students to write a 750-word essay, they need to be able to construct a proper thesis statement. Otherwise, what are they writing about?

Plan your assignments to build upon each other. Start with the most discrete building block of a skill, and then add to it in successive assessments. For example, before I ask students to write a 750-word essay, they need to be able to construct a proper thesis statement. Otherwise, what are they writing about?

This sounds obvious, but you would be surprised by how many veteran teachers just throw excrement at a wall to see what sticks. If you have not figured out what you are trying to accomplish in the classroom, that is your problem, not your students’. Do not ask kids to find meaning when you cannot.

I am ruthlessly organized. “Obsessive” has been bandied about. Fortunately, kids like an organized teacher.

For all my classes, students are given the syllabus for the entire term (or year!) on day one. They know what the plan is for today, what it is for tomorrow, next week, for exam prep, and so on. In this way, it is like a college course. I can do this because I have taught the same courses several times (ahem…dozens of times) in a row. But even by year two or three, I had a working syllabus going.

Why? It goes back to valuing kids’ time. They know that their back-to-back travel game nights are going to get busy, so they want to get ahead with the history reading. Guess what? They can! They have the syllabus in their notebooks and online. (Pro tip: I don’t date my syllabus. It’s Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, etc. in order.)

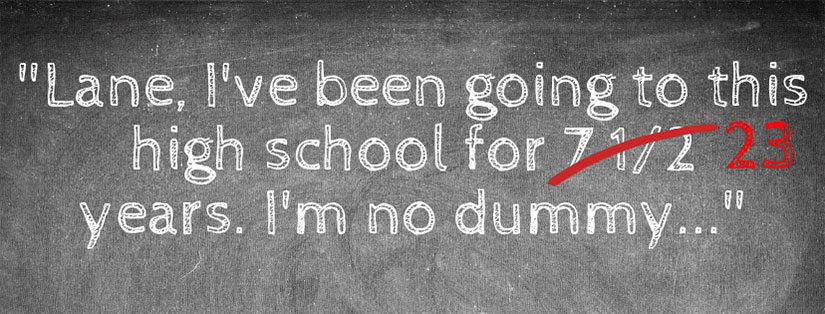

As you can probably tell from the above advice, I over-prepare for every lesson, new or old. Even if I have taught the lesson 23 times, I still go over my notes. I reread most of the readings every time, too. (Admittedly, it’s a little easier when you are re-reading something that you have already annotated and highlighted. That’s a point I make to my students while teaching note-taking.) Reviewing everything is important: the material must be as fresh to you as it is to them. If your students know better than you what was included in the reading you assigned, then shame on you.

As you can probably tell from the above advice, I over-prepare for every lesson, new or old. Even if I have taught the lesson 23 times, I still go over my notes. I reread most of the readings every time, too. (Admittedly, it’s a little easier when you are re-reading something that you have already annotated and highlighted. That’s a point I make to my students while teaching note-taking.) Reviewing everything is important: the material must be as fresh to you as it is to them. If your students know better than you what was included in the reading you assigned, then shame on you.

Now, let’s say you’ve put together the best lesson plan of all time. I mean, they should give you a Nobel Prize of Lesson Plans based on this thing, right? But you might still need to scrap it. Sometimes, you realize that the students are not ready for what you’ve prepared. Or, gulp, your technology fails you. Improvise. Be flexible. Figure it out. Think on the fly. Make those minutes count. Teach it a new way.

This matters in class and in your assessments. It is okay to be a tough teacher. You may think the “cool teachers” give everyone good grades, but here’s a secret: smart kids want to earn their grades. They want to achieve something they did not think previously possible. And they do not want to get the same grade as a kid who half-assed it. If you give everyone an A, they will know you do not respect their effort or their time.

This matters in class and in your assessments. It is okay to be a tough teacher. You may think the “cool teachers” give everyone good grades, but here’s a secret: smart kids want to earn their grades. They want to achieve something they did not think previously possible. And they do not want to get the same grade as a kid who half-assed it. If you give everyone an A, they will know you do not respect their effort or their time. Never, ever, ever have “A students.” Every student comes into an assessment as a totally new individual. If a normally top kid turns in crappy work, then he or she gets a crappy grade. (If that student is truly capable, he or she will recover.)

Never, ever, ever have “A students.” Every student comes into an assessment as a totally new individual. If a normally top kid turns in crappy work, then he or she gets a crappy grade. (If that student is truly capable, he or she will recover.)

All of this seems so obvious, but the biggest complaint that I hear from students is that a teacher has pegged them as an 82, and no matter how hard they work on something, they get essentially the same grade. This is a big problem in essay grading, which can be somewhat subjective. How can you be sure that you are grading the work fairly? Well…

I hate eduspeak acronyms and pedagogical platitudes. But I do like using good rubrics. Design your own. They keep you honest. Let me use an example from teaching history. Compare student A, who uses accurate, specific evidence in an essay, but she does not use it to prove a consistent argument; versus student B, who creates a brilliant thesis argument, but her evidence is thin. How do you grade these two against one another?

I hate eduspeak acronyms and pedagogical platitudes. But I do like using good rubrics. Design your own. They keep you honest. Let me use an example from teaching history. Compare student A, who uses accurate, specific evidence in an essay, but she does not use it to prove a consistent argument; versus student B, who creates a brilliant thesis argument, but her evidence is thin. How do you grade these two against one another?

Already I have set up the question in an unfair way. Do not judge them against each other. That is not fair, nor is it a transparent standard. You cannot show the students each other’s essays as a basis for a grade. Not only is it a violation of privacy, it is a standard that did not exist when the original essay was being drafted. No one wants to be graded on a moving target.

By using a rubric, you will be giving students A and B concrete feedback on how to improve—the most important job of a teacher. You will be giving this feedback without even writing a word of commentary, too. (Though I recommend at least a few comments on every assignment.)

So, what’s the answer to the question: would student A or B score higher? Honestly, it would depend on the whole rubric picture. I cannot say for sure. Sorry. (See my analytical essay rubric, Essay Rubric Hallock Sample , for more information. Feel free to use any part of it you find helpful in your classroom.)

My rubrics do not have a category for effort. I evaluate tangible quality markers, like proofreading or following directions—but how can you really judge effort? On the student’s say-so? There are a lot of kids who work very, very hard, and they will never boast (or whine) about it.

Now, sometimes you meet with a student a lot, and you can see the hard-won improvement. Definitely, compliment the student on their determination, and tell the parents about it in the written comments home.

But if a student understood a task the first time around, should he or she be effectively punished? Or what if he or she worked very hard to develop good skills last year, and it has made their job this year easier? This is not golf; do not handicap them for proficiency.

You are always safe if you grade the work on the page. End of story.

Kids ask for extensions, extra credit, extra points, more, more, more. Know that every advantage you give one student may be a disadvantage to another, so think through each case carefully. Every time a student asks me for something, I mentally prepare myself to say no while they are still speaking. I have said no a lot.

Your school will have procedures that make these decisions more straightforward: automatic extensions due to illness, the maximum number of tests a student can take in a day, and so on. And sometimes life happens—things beyond a kid’s control—and you give the extension because it is the right thing to do. But, before you do, imagine having to explain your choice to another student, one who did not get the extension. If the student who didn’t get the extra time would still agree with the fairness of the extension, then you’re good.

Fair. Consistent. Transparent. That’s the gold standard.

There is one syllabus that I have taught for 12 years, three sections a day. You would think those kids would know it already, right?

No. Every class is new. Every year you have to start from zero. ZE-ro.

All that great teaching you did last year, when you took your kids from barely coherent paragraphs to brilliant cohesive essays? When they went from plot summary hell to analytical writing heaven? Well, those kids have gone on to delight another teacher, not you. And you get to go back to explaining that, yes, students really do need to write their answers in complete sentences because this is high school, for goodness sake!

As a teacher, your job is not to get smarter. I mean, you will. It happens. But your job is to make them smarter. That means sometimes you are going to be a little bored by stuff you already know. Suck it up, buttercup.

One of the best ways to make every year different is to let the students imprint their own curiosity, personality, and character on the class. Let them talk, as long as they talk to the group, not their neighbors.

Students ask great questions. Let them struggle with the material a bit. You will clear up their confusion in a minute or two. Let them invest themselves in the question first, and then help them find the answer. (And if you do not know the answer, be honest and say you will get back to them.)

Students also know a surprising amount of stuff from other teachers, books they have read, personal experience, and more. Let them learn from each other.

Activities that require the kids to participate—debates, games, simulations, labs, and more—are wonderful. I like to have my students do occasional seminars, in which I am not allowed to say a word for 30 minutes or more. I listen to them and evaluate how well they use the reading in their arguments and questions. These seminars tend to crystalize around critical issues that we would have never discussed had I merely lectured.

Almost every piece of advice will boil down to this. When training intelligence officers, the CIA says that the best lie is one that is closest to the truth. You are less likely to be exposed this way. Well, kids are a suspicious lot: if you pretend to be something you are not, they will expose you like the KGB spymasters they are.

Moreover, assimilation is not a good exemplar. Most of your kids feel like misfits in one way or another, no matter how much confidence they project. (High school sucks, remember?) Let them see that adults, at least, are allowed to be themselves. Don’t rob them of this hope in the toughest time of their lives.

I am a history geek, and I embrace it. I am also oblivious to a lot of pop culture. The kids don’t care. I reach some kids more than others, but I am not the only teacher in the school. All of us as a team provide the support that the student body as a whole needs.

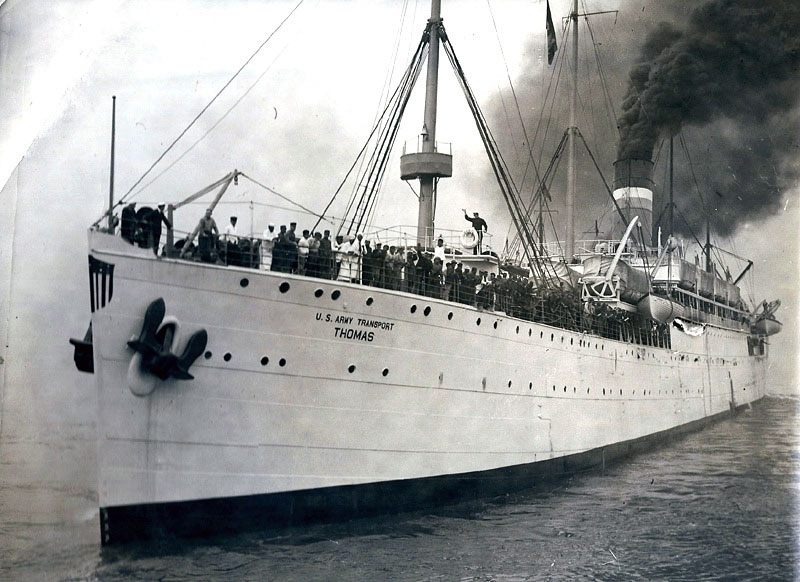

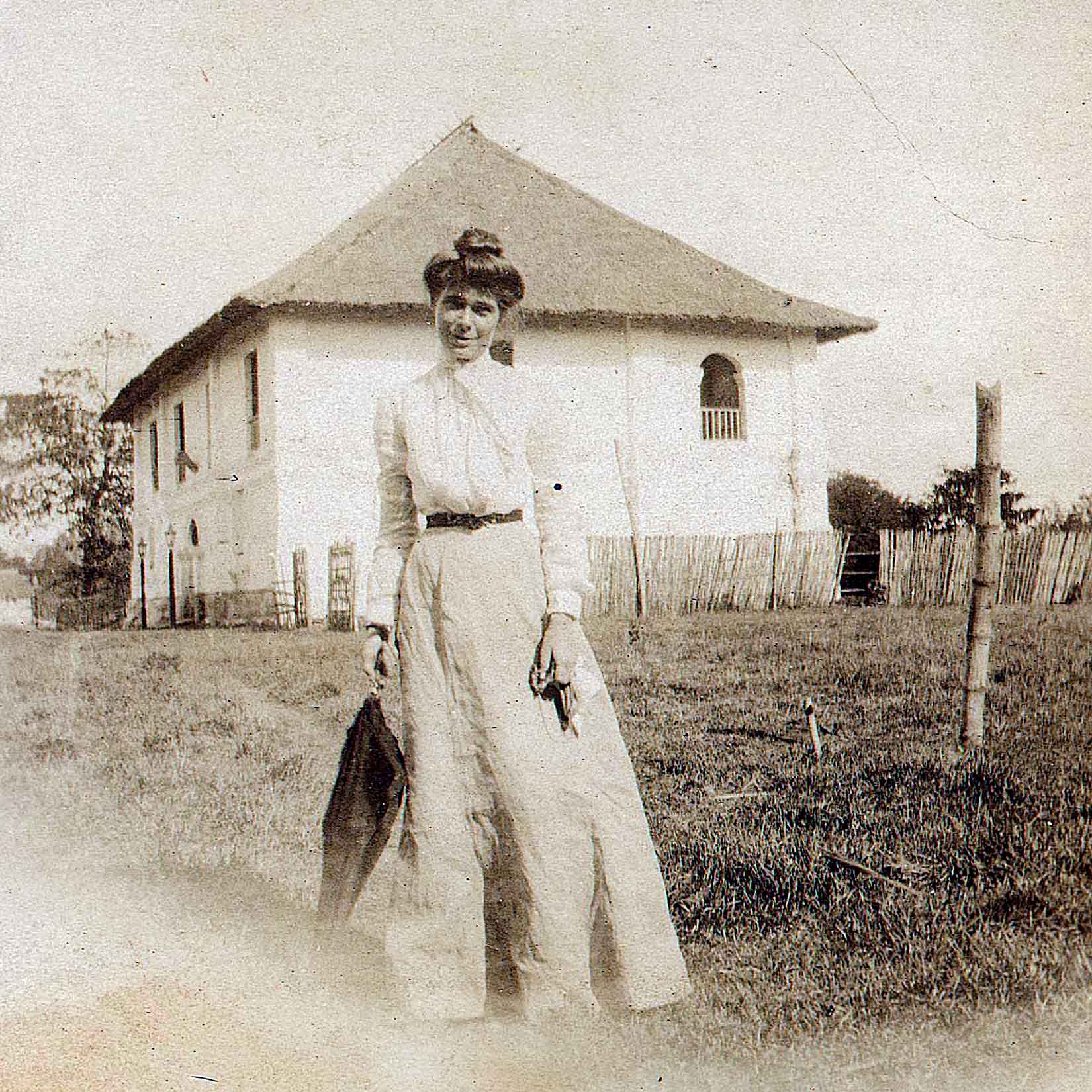

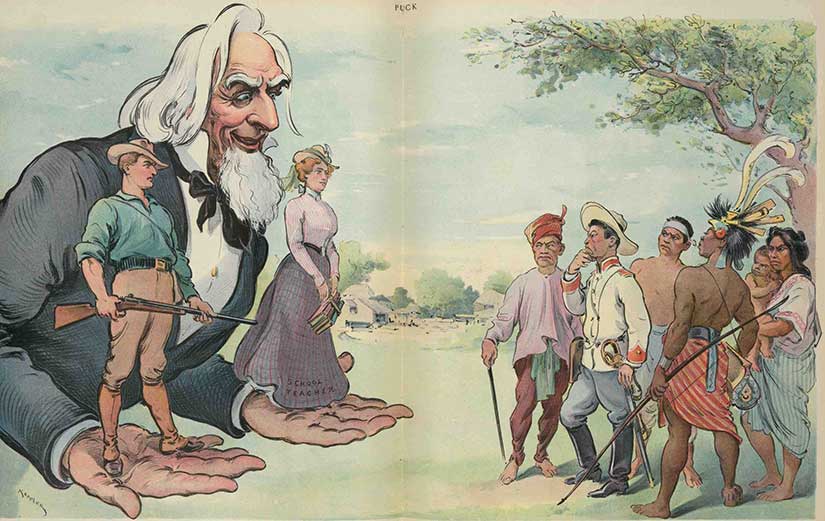

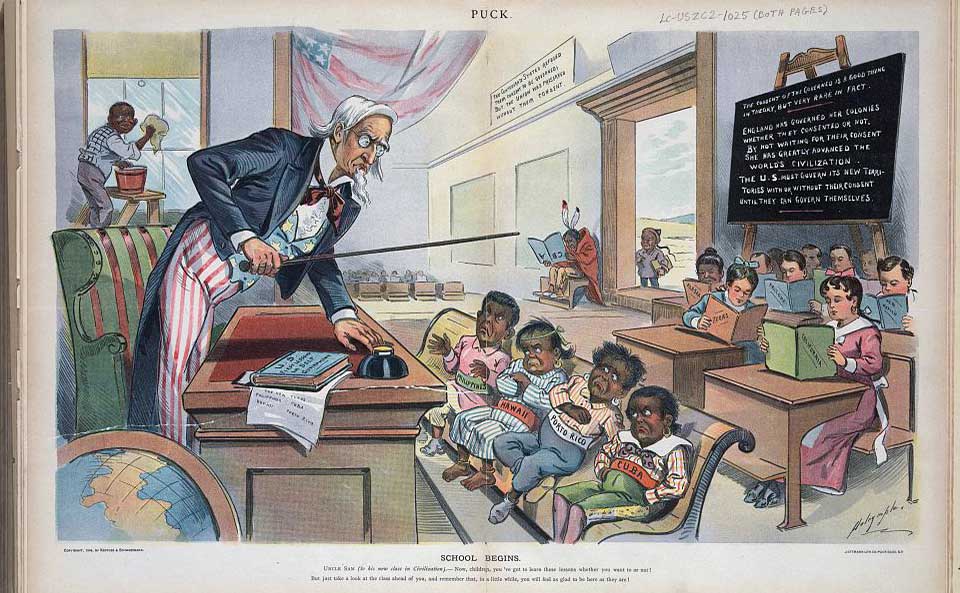

Binge-watch Netflix on the weekends. Paint. Do jigsaw puzzles. Knit. Play rec league hockey. Form a fantasy football league. Write a book. (Or a whole historical romance series set in the American colonial Philippines. No, wait, I did that already.) You need something other than school to keep you human. You will do your job better if you value something other than your job. Sneaky logic, ain’t it?

I hope this post has been useful. I do not know why I am putting it on my romance author blog—but since this is my best platform, here it is. Also, I have noticed that a disproportional number of authors are also teachers. And if you say, “Those who cannot do, teach,” then you probably did not care to read this far to begin with. And I’m sticking my tongue out at you. So there.