I am lucky. I get to teach important stuff that few survey classes touch. By the time US history teachers get to the Spanish-American War, they have one eye on the Great War and everything it sets in motion, and the other eye on the AP test coming up likely in a matter of weeks. Most students I talk to bemoan the fact that they barely cover Vietnam, and their teachers are likely a lot more familiar with Vietnam than the Philippine-American War. If they cannot cover My Lai, Woodstock, and Agent Orange, how can they find time for Balangiga, the Lodge Commission, and the water cure? (Well, some students do, and in the eighth and ninth grade no less!)

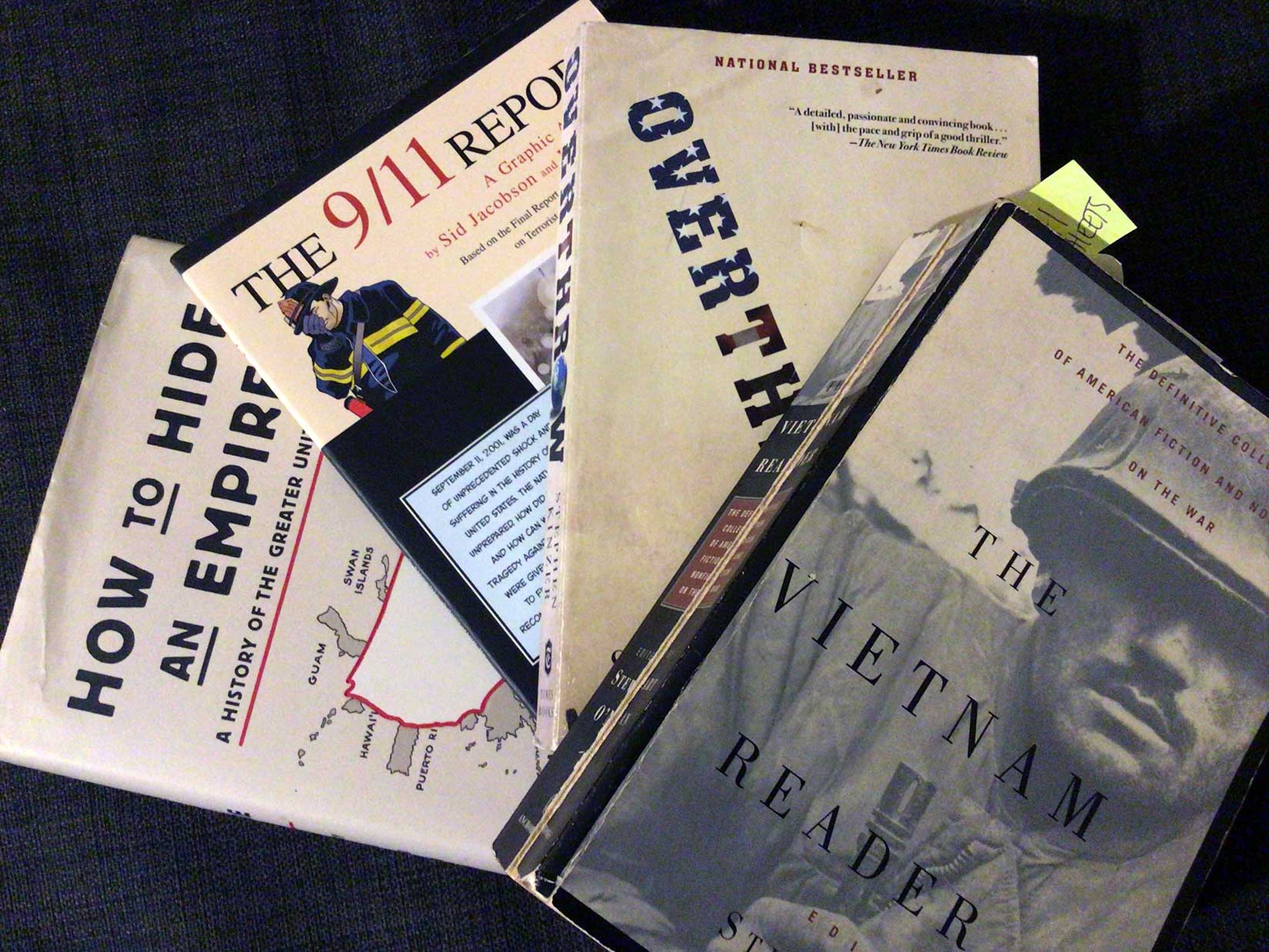

I teach trimester electives to mostly high school seniors about American empire and war in the Philippines (and China, Hawaii, Japan, and Pacific islands), in Vietnam (and Cambodia and Laos), and in Iraq (along with Iran, Afghanistan, and more). I try to add value with my own synthesis and analysis, but simply assigning the right readings is the first step to knowledge. I thought I might share some recommendations, not all of which are pictured above. Note that I make no money off the sales of these books, nor have I received any free copies or compensation for endorsing them.

How to hide an empire

This book by Daniel Immerwahr is, in his own words, not really new information—but considering how deftly he weaves together the many threads, you might think it is. How to Hide an Empire is a sweeping history of US expansion since independence, when what we call a republic was actually as much undefined territory as it was incorporated state. It’s eye-opening in a red-pill Matrix way, yet it manages to be entertaining and even funny. How did American Pacific empire between with bird shit? True story. How did overseas US bases inspire the Beatles and Sony? And what does the base system look like now, and why don’t Americans hear about it more in the news?

I would recommend this book to everyone from young adults on up, but I think it is especially important for US citizens. Though I use it as “homework,” it does not feel like it to my students. Many of them choose to read the portions we have not assigned in class because it is that good.

overthrow

While How to Hide an Empire paints the forest vividly, with the occasional tree, Overthrow by Stephen Kinzer is a neat row of evergreens at a Christmas tree farm. And just like that row planted by some agri-corp eager to make a profit off idealistic, family-farm nostalgia, Kinzer lays out difficult truths of big business behind seemingly altruistic goals. Each chapter takes the reader through the spy-thriller-esque story (but darker) of every time the US has overthrown a foreign government.

Sometimes the role was at least in part unofficial—a cabal of American-born landowners overthrew the queen of Hawaii, but they probably would not have succeeded had the US envoy not landed the Marines on shore in support. But sometimes the role was very much official, such as when the CIA overthrew the popularly-elected prime minister of Iran in 1953. Kinzer has individual titles that dig more deeply into individual cases, such as his books on the debate over the seizure of the Philippines, the coups in Iran and Guatemala, and the unbelievable Cold War origins when the leaders of US covert and overt foreign policy were brothers! And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

The 9/11 report: a Graphic Adaptation

The authors of the first published 9/11 Report intended to make the text readable because they wanted to reach the widest range of Americans possible, to answer the “Why?” questions better than the television networks were doing. But it was a big book, with, you know, lots of words. In my class I use this visual adaptation, and it is often the first time that my students have a teacher using a graphic novel as an instructional tool. They find that disconcerting because my students—wonderful as they are, and they are wonderful—like order and predictability. Shaking up the strict left-to-right line-by-line structure does put them off their game at first, but they get the hang of it. And they love the massive amounts of information this graphic novel version gives them in just a few days of assignments.

The vietnam reader

I teach a high school course, not university, on America in Vietnam, so I do not have the time to dig deep into the masterworks of nonfiction or fiction on the war in one trimester. This collection includes excerpts in a single volume, including: memoirs like If I Die in a Combat Zone (Tim O’Brien), Born on the Fourth of July (Ron Kovic), A Rumor of War (Philip Caputo); reporting and oral histories like Dispatches (Michael Herr), Nam (Mark Baker), and Bloods (Wallace Terry); and fiction like The Things They Carried (Tim O’Brien), Going After Cacciato (also Tim O’Brien), and more. The collection also includes essays on the major films of the war, along with relevant song lyrics. If you want the flavor of a little bit of everything, like a buffet on the American experience of the war, this single volume will do it. I have used it for so long that my book has literally broken into two halves. (No, I am not careful with my spines, don’t @ me, bibliophiles.)

There are many great works on the war not in this volume, probably because an excerpt would not do them justice. I highly recommend A Bright Shining Lie (Neil Sheehan) for understanding how “body count” and “search and destroy” were the exact opposite of what counterinsurgency strategy should be, as told through an engaging biography of a deeply flawed veteran and intelligence officer named John Paul Vann. For the Vietnamese perspective, When Heaven and Earth Changed Places (Le Ly Hayslip), puts you in the shoes of a woman in Central Vietnam who simply wants to stay out of the line of fire. There are more books written by other Vietnamese authors recently, which is terrific, but I still go back to this one because it is such a simple premise and yet so universal.

An American Requiem

I borrowed this memoir by James Carroll, one of several he has written, from my local library. Yours probably has it too. Its full title is An American Requiem: God, My Father, and the War that Came Between Us. As you can tell from the subtitle, this book is also partly a biography of his father, the founder of the Defense Intelligence Agency at the Pentagon. Carroll grew up an Air Force brat tooling around East and West Berlin in fast cars, then went to seminary and became a Catholic priest. (Not surprisingly, that is why I initially picked this up. Carroll took off his collar and was eventually granted a dispensation, and his more recent works, like The Truth at the Heart of the Lie, deal with the issues he sees with the priesthood as currently constituted. I recommend those too, as well as his latest fiction, The Cloister.)

Carroll became an anti-war activist, and though he was not quite as important to the resistance as the Berrigan brothers, Daniel and Philip, his bravery was not in doubt. He had a lot at stake in challenging his own family’s privilege, yet he did it. At his first Mass at an Air Force chapel on base, he made a statement against the use of napalm and Agent Orange—the bread and butter of the USAF during the war. I cringed as I read through this scene, and not because I don’t agree with Carroll. It was really uncomfortable, yet bold.

What I also love about this memoir of the early period of the war is how clearly Carroll shows the complicity of the American Catholic Church, especially Archbishop Francis Cardinal Spellman, in the war. Spellman helped handpick President Diem, and even after Diem’s removal and assassination, he and his subordinates continued to support the war effort unquestioningly. One of Carroll’s first novels, The Prince of Peace, carries this Cold War loyalty as a big theme.

That’s the list…for now

I also teach about America’s involvement in the Middle East and Southwest Asia, including especially Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan. Other than the Overthrow volume, though, I tend to use a lot of chapters from other works, not a single volume. As I find other relevant works, I will add them here. I should also point out that this reading list is not sufficient for understanding the full story of American history. The focus of my teaching is about US imperialism and neocolonialism, helping people understand the American footprint abroad. There are many, many more important books for understanding domestic history. To start this journey, I recommend Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (Ibram X. Kendi) and Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (Dee Brown).