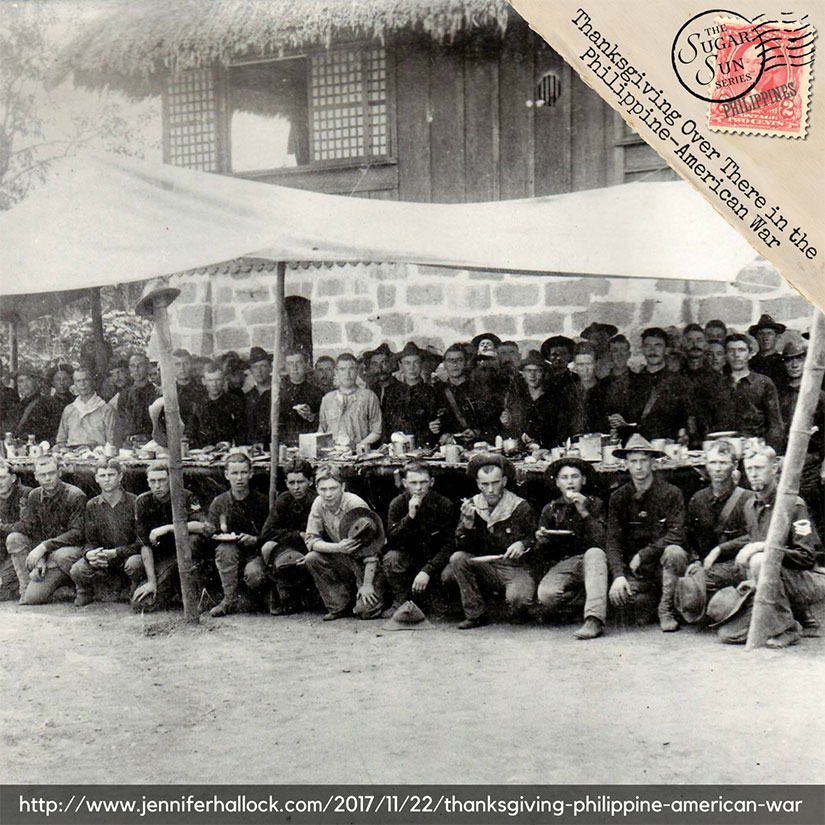

Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday of the year—and not just because I am a good eater. The real directive of this day is to look at our glass and see it is half full—and then, yes, drink it down. I write romance for the same reason. As Alisha Rai tweeted, “Remember our basic genre requirement today: there’s no black moment that love can’t overcome.”

It is fitting, therefore, that this national holiday was born out of a time of war—the Civil War.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. George Washington first proclaimed a day of thanksgiving in 1789, but he did not designate when it had to be commemorated. Each state was left to honor the holiday on a day of its own choosing—when they honored it at all.

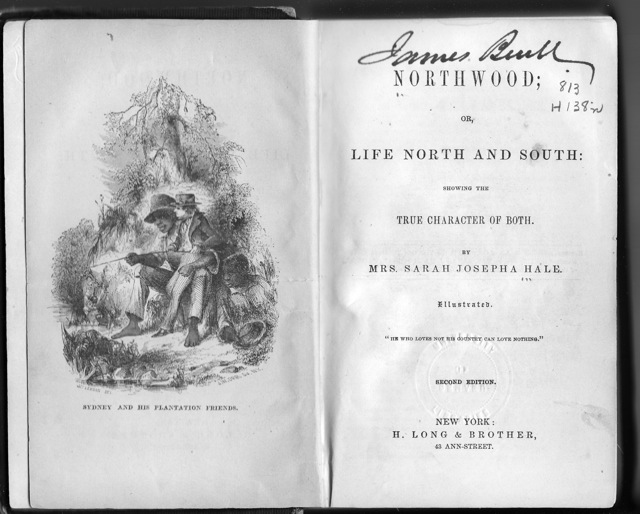

The regions of the country honored it differently, too—and the variations were featured in a 1824 novel called Northwood: A Tale of New England. An entire chapter was devoted to a New Hampshire-style celebration, complete with carved turkey, stuffing, cranberry sauce, and lots and lots of pie.

Mr. Hallock and I live in New Hampshire, and I have to admit that we buy our pie, not make it. Before you judge us, know that Just Like Mom’s pies are the best. They have many awards to prove it. We will be picking up our pumpkin and apple pies early tomorrow (Wednesday) morning, in fact.

We have already completed our first stage of official holiday observation, though. Because our official “friends-giving” in New Hampshire will be vegetarian—as per our guests’ dietary needs—Mr. Hallock and I ate our traditional dinner tonight, Tuesday, with ingredients delivered by Blue Apron. I made cranberry sauce from scratch people. Eat my shorts.

Okay, back to the Civil War. You see, Northwood was more than a manual on a proper Thanksgiving—it was an abolitionist tract that proudly touted the New Hampshire way as the way of prosperity and progress. Its author, Sarah Hale, also known as the “Mother of Thanksgiving,” wrote to President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 to tell him that he needed to create a united celebration of the blessings of the nation in order to mend the rifts of the Civil War. Apparently all we needed to get along was tryptophan. Hale argued:

You may have observed that, for some years past, there has been an increasing interest felt in our land to have the Thanksgiving held on the same day, in all the States; it now needs National recognition and authoritative fixation, only, to become permanently, an American custom and institution.

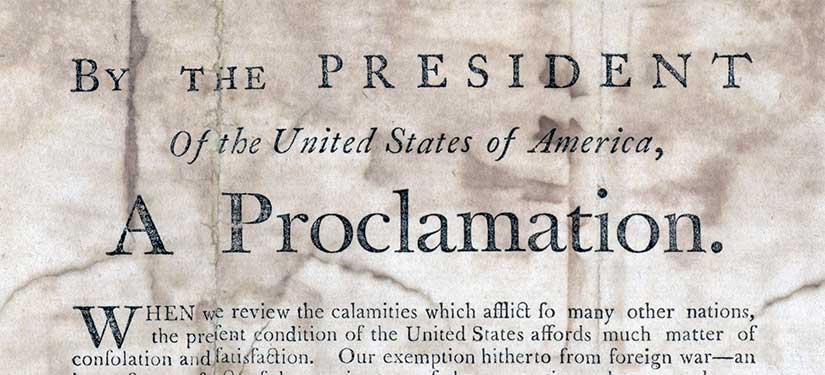

Whether in direct response to Hale’s pleas or not, President Lincoln declared a national Thanksgiving Day in 1863.* Lincoln claimed the turkey menu was his favorite, fitting in with Hale’s vision. His proclamation, originally penned by his Secretary of State William Seward, said:

I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity, and Union.

May your thanksgiving bring the warring sides of your family together again. And, in case that does not work, go somewhere quiet and read a romance novel!

Featured image: Thanksgiving postcard circa 1900 showing turkey and football player, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

* (Notes for history geeks: Both President Lincoln and Confederate President Jefferson had previously declared days of thanks—or days of fasting—depending on recent victories or losses, respectively, on the battlefields. But the declaration of 1863 (and Union victory in 1865) made the custom permanent throughout the United States. Interestingly, in 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved Thanksgiving up a week to draw out the shopping period before Christmas. He had hoped to give the economy a fiscal boost, but when 16 states refused to change the date, he was left with “dueling Thanksgivings.” He backed down again two years later.)